Since May 2020, Operation Warp Speed has been charged with producing and delivering 300 million doses of a COVID-19 vaccine by January 2021. While the scientific and technical challenges are daunting, the public-health challenge may be equally so. In the last two decades, anti-vaccination groups disseminating misinformation about vaccines have proliferated online, far outstripping the reach of pro-vaccine groups. Viruses that had become rare, such as measles, have now experienced outbreaks because of declining vaccination rates. The anti-vaccination movement was already poised to sabotage the COVID-19 vaccine uptake.

And now, as with all aspects of COVID-19, politics has crept into the vaccine conversation in ways that threaten to derail public confidence in a potential treatment key to halting the pandemic. Without trust in the efficacy of a vaccine, it is far less likely that society will reach herd immunity through vaccination.

So how can politicians convince large swathes of the American public to take a vaccine once it becomes available? The answer may be counterintuitive, but simple: Keep mum, and let the scientists and public-health experts share the facts with the American people.

In a study of American attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccination, just published in the Journal of the American Medical Association Network Open, we found that Americans’ support for vaccination declines in the face of political involvement in the vaccine process.

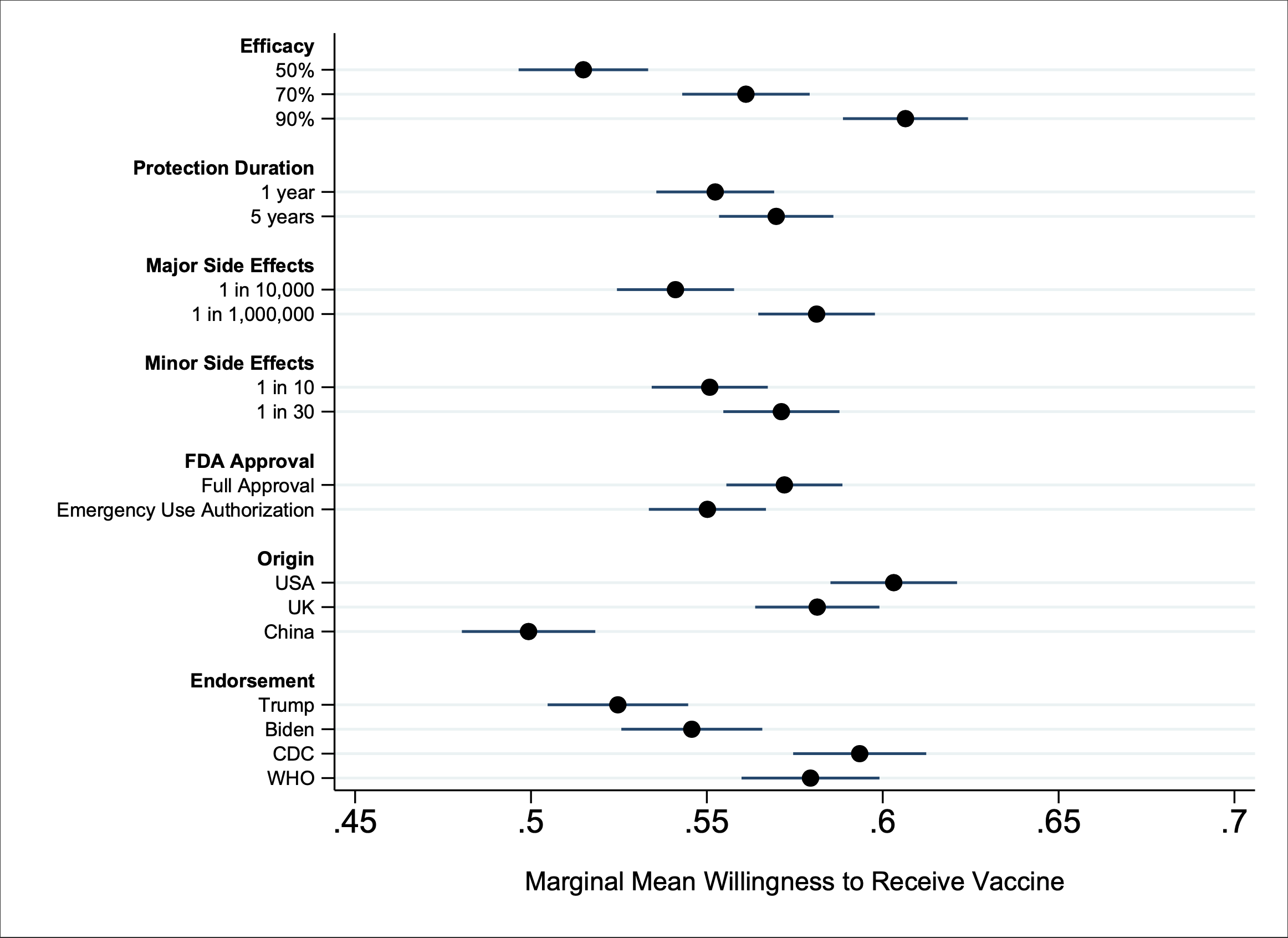

A Trump endorsement dampens the likelihood that individuals will vaccinate (see Figure 1). A Biden endorsement fares no better statistically. Despite missteps by the World Health Organization and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in responding to COVID-19, endorsements by either would be a more powerful lure for Americans than either a Trump or Biden endorsement.

Presidential politics have influenced vaccination policy before—and with disastrous results. Battling for reelection in 1976, President Ford aggressively promoted mass vaccination against a swine flu identified at Fort Dix, raising the specter of a repeat of the 1918 pandemic. The rollout was a mess; the flu pandemic never materialized; and the vaccine itself produced multiple cases of Guillain-Barre syndrome, which ultimately shut down the vaccination program and undercut public confidence in vaccines for years.

With his own reelection bid looming, President Trump’s efforts to accelerate Operation Warp Speed have prompted scientists to publicly warn against the dangers of rushing and politicizing vaccine development. Far from assuaging concerns about political pressure, Trump has even boasted that “no president’s ever pushed” the FDA like he has. New York Governor Andrew Cuomo alleges in his new book that the president’s chief of staff had implied a quid pro quo: Either New York hospitals accelerate the production and reporting of test results for the drug hydroxychloroquine, which Trump had lauded as a treatment for COVID-19, or the administration would withhold federal hospital aid. Such blatant politicization risks exacerbating public skepticism about vaccination and undermining public-health efforts to widely distribute the vaccine when it becomes available.

Bringing a vaccine to market under an FDA Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) is also more likely to raise concerns about politicization. Individuals will be more likely to infer political motives of expediency for the emergency approval than the FDA approval process (which has the added epidemiological benefit of more fully uncovering the risks and benefits of the vaccine). Our results suggest that using this expedited procedure would decrease public willingness to get vaccinated, producing a 3% drop in our study. This may not sound large, but it amounts to almost 10 million Americans choosing not to vaccinate.

And if the public perceives this process to be politicized and anything less than fully transparent, the adverse effect to public willingness to vaccinate could prove far greater still.

It now seems almost certain that the first vaccine will not be available until December 2020 at the earliest, dashing hopes of a fall approval. Perhaps the silver lining with this timeline is that it removes electoral politics from the equation. Absent political pressure to push for an October surprise, when the FDA ultimately does authorize a vaccine, Americans may be more willing to believe that science, not politics has guided the decision.

An effective public-health strategy should incorporate what we are learning about public attitudes toward the COVID-19 vaccine. And what we are learning clearly indicates that politics has no place in the vaccination process.

Politicians of all parties and offices—the highest office included—need to make a concerted effort to keep their endorsements and ambitions far away from both the development and messaging surrounding a COVID-19 vaccine. This is important not only for a vaccine’s safety and efficacy, but for Americans’ willingness to accept a vaccine at all.

Science-driven institutions such as CDC and WHO have more influence over Americans’ trust in a vaccine, and even an FDA that demonstrates a thorough, unbiased and careful approval of a vaccine can diminish vaccine skepticism. Social media platforms have been privileging authoritative content regarding COVID-19 from groups like the World Health Organization and Centers for Disease Control in in user searches and timelines. Our research suggests that those policies may have the added benefit of surfacing vaccine endorsements that increase adoption among the public.

Assuming that the world after vaccine availability will suddenly be different than before will require both a highly efficacious vaccine and a populace willing to take the vaccine. The public is looking to more than just efficacy. Its trust will hinge on something that is ambitious but not impossible: putting public health above politics, setting polarizing leaders aside, and allowing the FDA to do its work.

Sarah Kreps is a nonresident senior fellow in the Foreign Policy program at Brookings, the John L. Wetherill professor of government, and the Milstein Faculty Fellow in Technology and Humanity at Cornell University.

Douglas L. Kriner is the Clinton Rossiter Professor in American Institutions and faculty director of the Institute of Politics and Global Affairs at Cornell University.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Will Americans trust a COVID-19 vaccine? Not if politicians tell them to.

October 30, 2020