In an era of increasing media consolidation, devastating layoffs, and growing attacks on journalists’ ability to report the verifiable truth, fact-checking journalism stands out as a notable bright spot. As newsrooms contract, fact-checking operations are expanding. In 2019, there were 210 active fact-checking organizations in 68 countries, according to a survey conducted by Duke Reporters’ Lab. Poynter’s International Fact-Checking Network touts more than five dozen fact-checking organizations as verified “signatories” who adhere to a common code of principles. Some fact-checking organizations, like PolitiFact, partner with local newspapers such as the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel to bring fact-checking to local media markets.

Recent research we have done studying fact-checking journalism’s ability to help people become more likely to believe things that are true finds that fact-checks’ effectiveness is based on factors outside of journalists’ control. Instead, the effectiveness of fact-checks depends upon what we knew about an issue before encountering the fact-check (and whether we are willing to admit it if we don’t know much) and whether the story is clearly labeled as a fact-check.

Typically, researchers study political knowledge by assessing whether people know something or not. However, scholars have highlighted the importance of distinguishing between people who are certain about a misperception they hold as compared to those who are uninformed, but unsure, about their belief.

In one study surveying about 500 Americans, we decided to distinguish between different kinds of political informedness. Some people know a fact and are confident that they know it. We call these folks “informed.” Others are aware that they do not know some important facts about civics or current events. These people, who answer knowledge questions on surveys by saying, “I don’t know” are “uninformed.” Others still believe, with a high degree of confidence, that they do know the answer to a particular question even though they are actually mistaken. We call these individuals “misinformed.” Other folks readily admit that they are just guessing when asked about a contemporary fact. Some guess right and others don’t; what is important is that they admit that they are not sure. We call them “ambiguously informed.”

We studied whether people’s informedness level affects whether they become more likely to get the facts right about a story after reading a fact-check. We quizzed people on a list of 25 facts that had been checked by a fact-checking group like PolitiFact or FactCheck.org while also asking the participants how sure they were of each answer. Then, we showed them a fact-check about one of the issues we quizzed them on earlier.

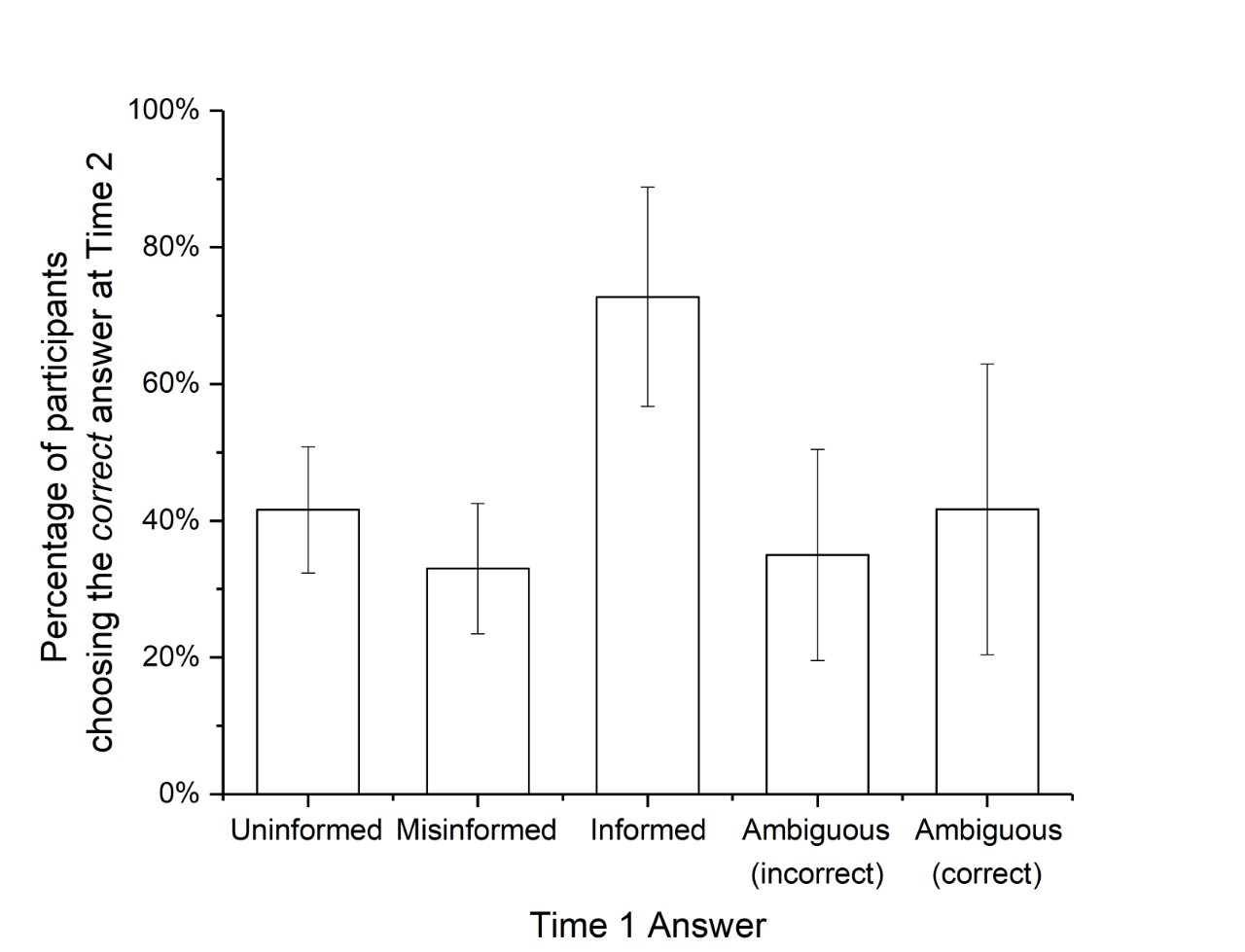

As the figure shows, people who were “informed” from the beginning were the most likely to be “informed” after reading a fact-check. However, the next most likely group to get the fact right had been “uninformed” just minutes earlier.

The “ambiguously informed” also showed improvement after reading the fact-check. However, the “misinformed”—the folks who were wrong but confident they were right—were the least helped by reading a fact-check.

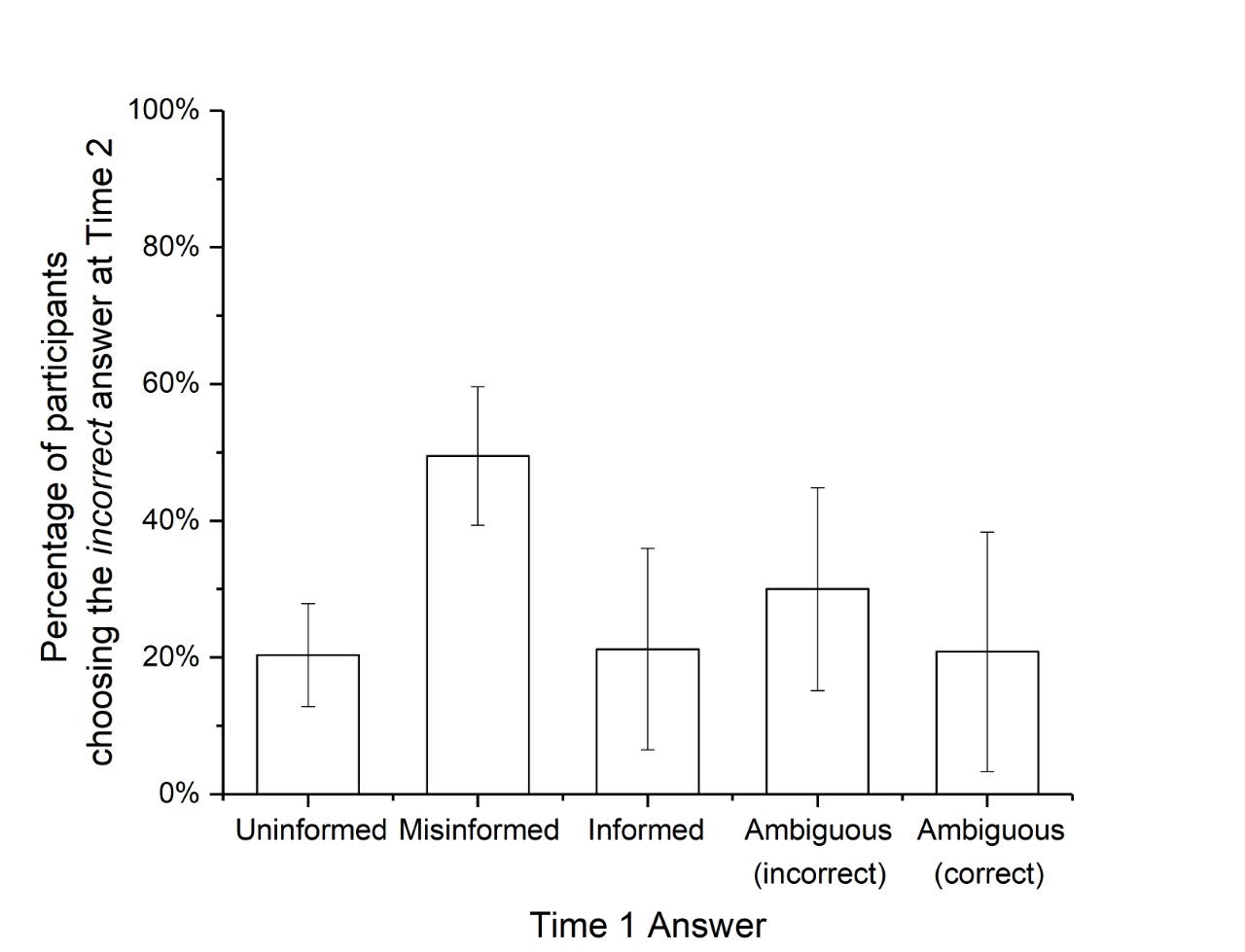

What’s worse, the figure below shows that the “misinformed”—even after reading a fact-check—are still more likely than not to choose the incorrect answer about the fact in question. All of the other groups become far less likely to choose an incorrect response option.

Next, we wanted to understand whether labeling a story as a fact-check was more effective at leading people to believe what is true as compared to a typical news story which does not directly adjudicate factual disputes. We conducted a large survey experiment on 800 Americans where some people read a fact-check that was labeled a fact-check in the headline and in the body of the story while others read the exact same story, only without calling it a fact-check.

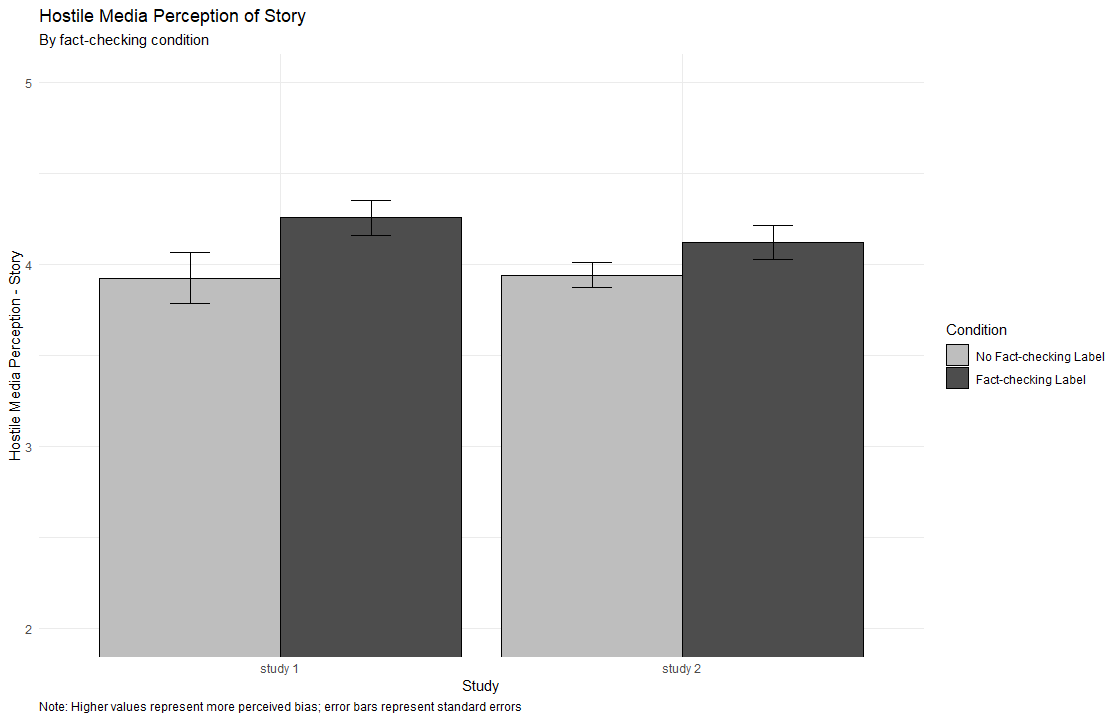

Sure enough, the fact-check label led people to perform better on questions about the facts of the issue. However, this benefit also came at a cost. Researchers have long known about the “hostile media effect”—the idea that people who care deeply about an issue will find balanced coverage of that issue hostile to their own point of view. Does this happen for fact-checks, too? Yes it does.

The figure below shows, across two separate studies of fact-check labeling, that while calling a story a fact-check helps people get the facts right, it simultaneously leads people to become more likely to report that the fact-check was biased.

Thus, journalists are faced with the extremely challenging tension of helping people learn facts—which they can do by clearly labeling fact-checks—while leading people to believe that their reporting is biased in the process.

While we have no trouble pointing fingers at the news media, blaming them for bias, if we really want to get better at understanding what is true, we need to look in the mirror and admit what we don’t know, take reputably reported corrective information seriously and update our attitudes accordingly.

Jianing Li is a Ph.D. student at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Michael W. Wagner is Professor of Journalism of Mass Communication at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and the Director of the forthcoming Center for Communication and Civic Renewal.

Commentary

When are readers likely to believe a fact-check?

May 27, 2020