In 2019, and again in 2020, Facebook removed covert social media influence operations that targeted Libya and were linked to the Russian businessman Yevgeny Prigozhin. The campaigns—the first exposed in October 2019, the second in December 2020—shared several tactics: Both created Facebook pages masquerading as independent media outlets and posted political cartoons. But by December 2020, the operatives linked to Prigozhin had updated their toolkit: This time, one media outlet involved in the operation had an on-the-ground presence, with branded merchandise and a daily podcast.

Between 2018 and 2020, Facebook and Twitter announced that they had taken down 147 influence operations in total, according to our examination of their public announcements of disinformation takedowns during that time period. Facebook describes such operations as “coordinated inauthentic behavior,” and Twitter dubs them “state-backed information operations.” Our investigation of these takedowns revealed that in 2020 disinformation actors stuck with some tried and true strategies, but also evolved in important ways, often in response to social media platform detection strategies. Political actors are increasingly outsourcing their disinformation work to third-party PR and marketing firms and using AI-generated profile pictures. Platforms have changed too, more frequently attributing takedowns to specific actors.

Here are our five takeaways on how online disinformation campaigns and platform responses changed in 2020, and how they didn’t.

1. Platforms are increasingly specific in their attributions.

In 2020, Facebook and Twitter were increasingly specific in attributing a given operation to a specific actor, such as specific individuals, companies, and governments. When a platform only says a network originated in a particular country, we don’t consider this specific; when they say it’s run by a particular government or group of people, we do.Based on our coding, approximately 76% of takedowns were attributed to a specific actor in 2020, compared to 62% in 2019 and 47% in 2018.

When specific, platform attributions publicly “name and shame” those who wage social media influence operations. Attribution won’t always lead to a change in behavior or embarrass the perpetrator, but it’s a starting point to deter potential disinformants and empower domestic citizens or the international community to respond. Specific attributions in 2020 included the Iran Broadcasting Company, the Royal Thai Military, and an IT company based in Tehran.

The frequency of specific attributions is noteworthy for a number of reasons. First, disinformants go to increasing lengths to hide their tracks. Platforms’ growing ability to attribute operations not just to a country, but to a government, and often to a specific actor within that government, reflects the substantial resources devoted to investigating operations and the remarkable collaborations between platforms, reporters, and civil society groups to expose them.

Second, the platforms often face costs to attributing operations. Sometimes it’s simple disparagement. Prigozhin responded to Facebook’s December 2020 attribution by stating, “Most likely, the era of Facebook will come to an end and states will finally close their borders to such political perverts.” At other times, it’s threats. After Twitter removed 7,000 accounts linked to the youth wing of Turkey’s ruling Justice and Development Party, a senior government communications official wrote that “we would like to remind [Twitter] of the eventual fate of a number of organisations which attempted to take similar steps in the past.” That threat came against the backdrop of tightening restrictions on online platforms in Turkey.

2. When the defense improves, disinformants innovate.

Offense and defense adapt to one another, and in 2020 the cat-and-mouse game between disinformation operatives and those trying to expose them evolved in interesting ways.

Fake accounts are a linchpin of influence operations, and a good fake account needs a profile photo. Propagandists won’t be effective if their identity is known, but behind the guise of a journalist or community member, their content has greater potential to persuade. While faux social media personas are nothing new, we’ve seen evolutions in how these accounts falsely present themselves. Perhaps the most interesting development is the use of AI-generated profile pictures.

Disinformation researchers have long used reverse image searches to catch propagandists who steal photos of other people. In response, disinformants evolved. Leveraging advancements in machine learning, they began using AI-generated profile pictures. The first takedown including AI-generated profile pictures “deployed at scale” took place in December 2019. AI-generated pictures are freely available, and, because they’re not of actual humans, they allow propagandists to evade reverse image searching. In 2020, we’ve seen at least seven takedowns of networks that use these computer-generated profile photos. They include domestic operations, such as a student group linked to the Communist Party of Cuba targeting the Cuban public, and interstate operations, such as a Russia-linked operation targeting the United States.

A second tactic to evade detection is handle switching. In 2019, we were often able to identify suspicious Twitter activity by looking up Twitter accounts on archiving sites. An account may have been involved in an operation targeting Sudan, then deleted all of its tweets about Sudan when shifting to a new operation targeting Morocco. Archiving sites allowed us to identify the account’s inconsistent public identity. In 2020, several disinformation actors started employing handle switching to evade researchers. With handle switching, users change not just their username and bio, but also their handles. For example, an account can go from twitter.com/john123 to twitter.com/jen123—while retaining its followers. This makes discovering and assessing their prior activity difficult or impossible.

One recently suspended operation on Twitter illustrates the potential of the handle switching tactic. Individuals linked to the Saudi government created Twitter accounts—three of them with more than 100,000 followers—and used these accounts to spread (quickly discredited) rumors of a coup in Qatar. The accounts posed as a Qatari interim government and dissident Qatari royals living in Saudi Arabia. The accounts had only assumed these identities recently; indeed, we do not know how they built such large followings, but it is possible they had previous lives engaging in spammy follow-back activity. But by deleting old tweets and changing their handles, accounts can start over while keeping large audiences, and researchers lack easy tools for assessing account validity.

Handle switching can also be used in an attempt to hide some assets after others have been exposed. According to Graphika, when Twitter suspended accounts used in a Russian operation employing social media users in Ghana to target black communities in the United States, the operation’s Instagram accounts “changed their names en masse in what can only have been a coordinated attempt to hide.”

Platforms can in turn adapt and design features that make things harder for bad actors. Facebook’s Page Transparency feature, for example, shows the history of a page’s name, which makes it harder for bad actors to engage in equivalent “handle” switching on Facebook. In 2021, Twitter could implement a similar feature.

3. Political actors are increasingly outsourcing disinformation.

In 2020, Facebook and Twitter attributed at least 15 operations to private firms, such as marketing or PR companies.The outsourcing of social media disinformation to third-party actors first gained notoriety in 2016 with Russia’s use of the Internet Research Agency, an ostensibly private company run by Prigozhin. Since then, third-party actors, from troll farms in the Philippines to strategic communication firms in the United States to PR firms in Ukraine, have been accused of running disinformation campaigns.

On its face, outsourcing disinformation is puzzling—if the operator wants to keep an operation secret, why risk exposure by adding a third party into the operation? But it also has benefits, including lending deniability. Technically, outsourcing makes it more difficult for a platform to link an operation to a sponsor. Technical indicators may suggest to a social media platform that an inauthentic network is run by a marketing firm, but the platform will likely lack digital evidence as to who ordered up the network in the first place. Politically, even if people can guess the likely sponsor, the PR firm caught red-handed offers political players a scapegoat.

But there may also be downsides to outsourcing. Governments may face principal-agent problems with disinformation firms for hire. While we do not yet know how governments measure the success of these firms, it seems possible that marketing firms might be able to meet certain quotas without having the impact that government clients think they’ve purchased. For example, in a now-suspended Twitter network linked to a Saudi digital marketing firm, we observed the firms’ accounts using “hashtag training.” Accounts would tweet a nonsensical series of hashtags—including long, convoluted ones that advertised the firm’s bug exterminator client and also spread political hashtags criticizing Qatar. We suspect the intention was to get these hashtags to trend. While that might make the digital marketing firm look good, it probably won’t result in the kind of organic hashtag usage the political client had hoped for.

4. All countries are not targeted equally.

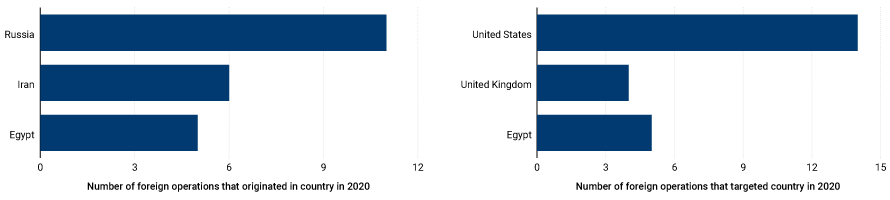

In 2020, certain countries were far more likely than others to be targeted by foreign disinformation operations in which a perpetrator targets people in another country. The most targeted countries by foreign actors, at least among takedowns publicly announced by Facebook and Twitter, were the United States, the United Kingdom, and Egypt. These countries were also the most targeted countries in 2019, though 2019 also saw several operations that targeted Qatar and Ukraine.

Why these countries are the most targeted is unclear. Geopolitical realities may make them more attractive targets. Ukraine and Qatar, for example, have strategic importance for Russia and Saudi Arabia, countries with strong disinformation capabilities. It could also be that domestic characteristics, like open media environments, make the United States and United Kingdom particularly susceptible.

But there are also real challenges in assessing what countries are most often targeted. First, these Facebook and Twitter takedowns are just that—takedowns on these two platforms. These takedowns don’t tell us about disinformation campaigns that leverage other platforms. In certain regions, other apps—like Telegram—may be more popular and a more likely avenue for information operations.

Second, because we don’t know what operations Facebook and Twitter failed to discover or chose not to publicize, platform takedowns don’t necessarily paint the full picture. It’s likely, for example, that takedowns are more common in places that platforms and researchers disproportionately investigate.

Third, sometimes these takedowns are not necessarily distinct operations, but rather are follow-ons from prior takedowns or cross-platform campaigns. This could lead to overcounting because accounts were missed the first time around or part of a network respawned. It also leads to double counting perpetrators who use both Twitter and Facebook as individual arms of a single, coordinated cross-platform effort.

Moreover, not all countries are equally likely to run disinformation operations. Facebook and Twitter most frequently attributed foreign influence campaigns to actors in Russia, Iran, and Egypt. These were the countries that most frequently carried out foreign operations in 2019 as well, based on our dataset.

5. Fake news outlets remain a popular tactic.

In both 2019 and 2020, the operations removed by Facebook and Twitter often included pages or accounts that pretended to be independent news outlets, continuing an earlier practice.

The use of fake news outlets is partially a byproduct of the democratization of the internet: New legitimate blogs and news sites pop up every day, and it is easy to hide in their midst.An information operation linked to the Islamic Movement of Nigeria—a group that advocates the installation of an Islamic form of government in Nigeria—included seven pages that claimed to represent NaijaFox[.]com, a pseudo-news site that published articles with an anti-Western slant. (The NaijaFox domain has since been seized by the FBI.)

While most fake media outlets used in information operations are original, some have assumed the identity of existing legitimate media outlets. A takedown in November of a network that originated in Iran and Afghanistan included a Facebook page and Instagram account pretending to represent Afghanistan’s most popular TV channel. A common tactic is to use “typosquatting,” changing just one letter of a Facebook URL so that the URL passes as legitimate at first glance. A report from CitizenLab documents how an Iran-aligned network used typosquatting extensively: Impersonating Bloomberg with a “q” (bloomberq[.]com) or Politico with a misspelling (policito[.]com).

As platforms increasingly monitor for information operations, bad actors may see greater value in investing in domains, which are less vulnerable to suspension. We have also seen disinformants drive traffic to third-party messaging apps that do not actively monitor for information operations—like encouraging Facebook users to join Telegram channels that are dedicated to their fake news outlets. Telegram is an encrypted messaging app based in Dubai and is not known to suspend disinformation content. We have repeatedly seen Facebook and Twitter suspend fake news accounts with linked Telegram channels, and the Telegram channels continue their activity as if nothing happened.

While the news outlets may be “fake,” the content itself is not always “fake” per se. Obviously untrue information does remain an issue in some of these networks—one somewhat outlandish example we saw recently included the obvious fabrication of an image of the Taliban to make it look like they were praying for President Donald Trump’s recovery from COVID-19. But much of the content we see in these operations is non-falsifiable—not true, but also not demonstrably false. Bad actors are using accounts to spread hyperpartisan content. We have seen, for example, Saudi-linked Twitter accounts pretending to represent ordinary Libyan citizens tweeting non-falsifiable cartoons mocking Turkey and Qatar.

Information operations and impact

The extent to which social media influence operations pose a threat is still an open question. On a tactical level, some of the operations clearly have limited impact. For example, in a recent operation attributed to the Royal Thai Army targeting Thai Twitter users, the average number of engagements per tweet (calculated as the sum of likes, comments, retweets, and quote tweets) was just .26 engagements. At the same time, on a broader strategic level, the threat may be more significant. Social media manipulation has second-order effects—citizens may believe these operations are successful, which erodes trust in the larger information ecosphere. As governments work to develop responses, it is imperative to begin with an understanding of how these operations work in practice, and to think through likely tactical innovations to come.

Josh A. Goldstein is a CISAC pre-doctoral fellow with the Stanford Internet Observatory and a PhD Candidate in International Relations at the University of Oxford.

Shelby Grossman is a research scholar at the Stanford Internet Observatory. She holds a PhD in Government from Harvard University.

Facebook and Twitter provide financial support to the Brookings Institution, a nonprofit organization devoted to rigorous, independent, in-depth public policy research.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

How disinformation evolved in 2020

January 4, 2021