Tom Wheeler recently appeared on the Lawfare Podcast to discuss the cybersecurity of 5G networks with Brookings Fellow Margaret Taylor. You can listen to the podcast episode here.

“The race to 5G is on and America must win,” President Donald Trump said in April. For political purposes, that “race” has been defined as which nation gets 5G built first. It is the wrong measurement.

We must “fire first effectively” in our deployment of 5G. Borrowing on a philosophy Admiral Arleigh Burke coined in World War II: Speed is important, but speed without a good targeting solution can be disastrous.1

5G will be a physical overhaul of our essential networks that will have decades-long impact. Because 5G is the conversion to a mostly all-software network, future upgrades will be software updates much like the current upgrades to your smartphone. Because of the cyber vulnerabilities of software, the tougher part of the real 5G “race” is to retool how we secure the most important network of the 21st century and the ecosystem of devices and applications that sprout from that network.

Never have the essential networks and services that define our lives, our economy, and our national security had so many participants, each reliant on the other—and none of which have the final responsibility for cybersecurity. The adage “what’s everybody’s business is nobody’s business” has never been more appropriate—and dangerous—than in the quest for 5G cybersecurity.

“As we pursue the connected future, however, we must place equivalent—if not greater—focus on the security of those connections, devices, and applications.”

The new capabilities made possible by new applications riding 5G networks hold tremendous promise. As we pursue the connected future, however, we must place equivalent—if not greater—focus on the security of those connections, devices, and applications. To build 5G on top of a weak cybersecurity foundation is to build on sand. This is not just a matter of the safety of network users, it is a matter of national security.

Hyperfocus on Huawei

Effective progress toward achieving minimally satisfactory 5G cyber risk outcomes is compromised by a hyperfocus on legitimate concerns regarding Huawei equipment in U.S. networks. While the Trump administration has continued an Obama-era priority of keeping Huawei and ZTE out of domestic networks, it is only one of the many important 5G risk factors. The hyperbolic rhetoric surrounding the Chinese equipment issues is drowning out what should be a strong national focus on the full breadth of cybersecurity risk factors facing 5G.

The purpose of this paper is to move beyond the Huawei infrastructure issue to review some of the issues that the furor over Huawei has masked. Policy leaders should be conducting a more balanced risk assessment, with a broader focus on vulnerabilities, threat probabilities, and impact drivers of the cyber risk equation. This should be followed by an honest evaluation of the oversight necessary to assure that the promise of 5G is not overcome by cyber vulnerabilities, which result from hasty deployments that fail to sufficiently invest in cyber risk mitigation.

Such a review of 5G cyber threat mitigation should focus on the responsibilities of both 5G businesses and government. This should include a review of whether current market-based measures and motivations can address 5G cyber risk factors and where they fall short, the proper role of targeted government intervention in an era of rapid technological change. The time to address these issues is now, before we become dependent on insecure 5G services with no plan for how we sustain cyber readiness for the larger 5G ecosystem.

The after-the-fact cost of missing a proactive 5G cybersecurity opportunity will be much greater than the cost of cyber diligence up front. The NotPetya attack in 2017 caused $10 billion in corporate losses. The combined losses at Merck, Maersk, and FedEx alone exceeded $1 billion. 5G networks did not exist at that time, of course, but the attack illustrates the high cost of such incursions, and it pales in comparison to an attack that would result in human injury or loss of life. We need to establish the conditions by which risk-informed cybersecurity investment up front is smart business for all 5G participants.

China is a threat even when there is not Huawei equipment in our networks. From the successful exfiltration of highly sensitive security clearance data in the Office of Personnel Management breach commonly attributed to China, to the ongoing China-linked threat actor campaign against managed service providers, many of China’s most successful attacks have taken advantage of vulnerabilities in non-Chinese applications and hardware and poor cyber hygiene. None of this goes away with the ban on Huawei. We cannot allow the headline-grabbing focus on Chinese network equipment to lull us into a false sense of cybersecurity. In a world of interconnected networks, devices, and applications, every activity is a potential attack vector. This vulnerability is only heightened by the nature of 5G and its highly desirable attributes. The world’s hackers (good and bad) are already turning to the 5G ecosystem, as the just concluded DEFCON 2019 (the annual ethical “hacker Olympics”) illustrated. The targets of this year’s hacker villages included key parts of the 5G ecosystem such as: aviation, automobiles, infrastructure control systems, privacy, retail call centers and help desks, hardware in general, drones, IoT, and voting machines.

5G expands cyber risks

There are five ways in which 5G networks are more vulnerable to cyberattacks than their predecessors:

- The network has moved away from centralized, hardware-based switching to distributed, software-defined digital routing. Previous networks were hub-and-spoke designs in which everything came to hardware choke points where cyber hygiene could be practiced. In the 5G software defined network, however, that activity is pushed outward to a web of digital routers throughout the network, thus denying the potential for chokepoint inspection and control.

- 5G further complicates its cyber vulnerability by virtualizing in software higher-level network functions formerly performed by physical appliances. These activities are based on the common language of Internet Protocol and well-known operating systems. Whether used by nation-states or criminal actors, these standardized building block protocols and systems have proven to be valuable tools for those seeking to do ill.

- Even if it were possible to lock down the software vulnerabilities within the network, the network is also being managed by software—often early generation artificial intelligence—that itself can be vulnerable. An attacker that gains control of the software managing the networks can also control the network.

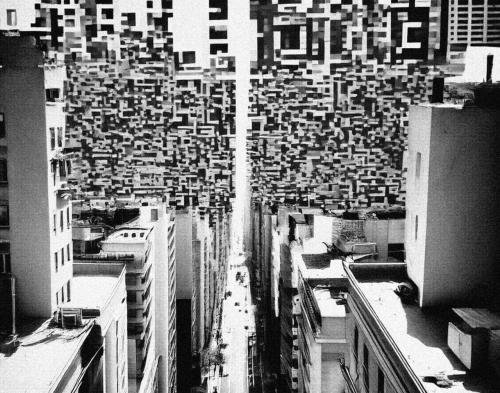

- The dramatic expansion of bandwidth that makes 5G possible creates additional avenues of attack. Physically, low-cost, short range, small-cell antennas deployed throughout urban areas become new hard targets. Functionally, these cell sites will use 5G’s Dynamic Spectrum Sharing capability in which multiple streams of information share the bandwidth in so-called “slices”—each slice with its own varying degree of cyber risk. When software allows the functions of the network to shift dynamically, cyber protection must also be dynamic rather than relying on a uniform lowest common denominator solution.

- Finally, of course, is the vulnerability created by attaching tens of billions of hackable smart devices (actually, little computers) to the network colloquially referred to as IoT. Plans are underway for a diverse and seemingly inexhaustible list of IoT-enabled activities, ranging from public safety things, to battlefield things, to medical things, to transportation things—all of which are both wonderful and uniquely vulnerable. In July, for instance, Microsoft reported that Russian hackers had penetrated run-of-the-mill IoT devices to gain access to networks. From there, hackers discovered further insecure IoT devices into which they could plant exploitation software.

Fifth-generation networks thus create a greatly expanded, multidimensional cyberattack vulnerability. It is this redefined nature of networks—a new network “ecosystem of ecosystems”—that requires a similarly redefined cyber strategy. The network, device, and applications companies are aware of the vulnerabilities and many are making, no doubt, what they feel are good faith efforts to resolve the issues. The purpose of this paper is to propose a basic set of steps toward cyber sufficiency. It is our assertion that “what got us here won’t get us there.”

5G service providers are the first ones to tell us that 5G will underpin radical and beneficial transformation in what we can do and how we manage our affairs. At the same time, these companies have publicly worried about their ability to address the totality of the cyber threat and have described the future challenge in disturbingly blunt terms. The president’s National Security Telecommunications Advisory Committee (NSTAC)—composed of leaders in the telecommunications industry—told him in November, “The cybersecurity threat now poses an existential threat to the future of the [n]ation.”

The nature of 5G networks exacerbates the cybersecurity threat. Across the country, consumers, companies, and cities seeking to use 5G are ill-equipped to assess, let alone address, its threats. Placing the security burden on the user is an unrealistic expectation, yet it is a major tenet of present cybersecurity activities. Looking to the cybersecurity roles of the multitude of companies in the 5G “ecosystem of ecosystems” reveals an undefined mush. Our present trajectory will not close the cyber gap as 5G greatly expands both the number of connected devices and the categories of activities relying on 5G. This general dissonance is further exacerbated by positioning Chinese technological infection of U.S. critical infrastructure as the essential cyber challenge before us. The truth is that it’s just one of many.

What have we learned thus far?

5G has challenged our traditional assumptions about network security and the security of the devices and applications that attach to that network. As officials of the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), the authors struggled to deal with these challenges only to be confronted by:

- Industrial-era procedural laws that make rulemaking activity cumbersome and non-rulemaking activity less than optimal.

- The incentive of bad actors to overcome any solution that is typically greater than the incentive to maintain the protection.

- Industry stakeholder fear of exposing their internally identified risk factors at precisely the time when sharing information about attacks would be of greatest value for a collective defense.

At the same time, those who know the networks the best—the network operators—exist under business structures that are not optimal for effective risk reduction. As an FCC white paper concluded three years ago:

As private actors, ISPs (internet service providers, such as 5G networks) operate in economic environments that pressure against investments that do not contribute to profit. Protective action taken by one ISP can be undermined by the failure of other ISPs to take similar actions. This weakens the incentive of all ISPs to invest in such protections. Cyber accountability therefore requires a combination of market-based incentives and appropriate regulatory oversight where the market does not, or cannot, do the job efficiently.

The FCC report’s finding—that market forces alone would not address society’s cyber risk interests—highlighted the ISPs over which the agency had primary jurisdiction. The report additionally examined the larger ecosystem and concluded that the motivation to solve the problem generally gets worse when consumers do not link a purchasing decision with a cyber risk outcome. This, unfortunately, is all too often the case, as service providers as well as device and application vendors do not make meaningful security differentiators public and don’t compete on any verifiable security indicators.

“None of this suggests that we suspend the march to the benefits of 5G. It does, however, suggest that our status quo approach to 5G should be challenged.”

In 2016, for instance, hackers shut down major portions of the internet by taking control of millions of low-cost chips in the motherboards of video security cameras and digital video recorders. That the internet could be attacked this way reflected the reality of digital supply chains: Because consumers didn’t consider cybersecurity in their purchase decisions of low-cost connected devices (they were the means, not the target of the attack), retailers didn’t prioritize security in their decisions of what to stock. As a result, manufacturers didn’t emphasize cyber in the components they purchased and thus chip and motherboard manufacturers did not include cyber protections in their product. None of companies defined a role for themselves for sustaining post-purchase product cyber readiness and, by and large, that’s still the case.

New industry verticals are bringing 5G-enabled capabilities to a market where good faith efforts are insufficient. There is no evidence that the business priorities of the suppliers of devices and applications are any different than those attributed to network operators in the FCC report. A 2018 report by the Trump administration’s Council of Economic Advisers, for instance, warned of, “underinvestment in cybersecurity by the private sector relative to the socially optimal level of investment.”

None of this suggests that we suspend the march to the benefits of 5G. It does, however, suggest that our status quo approach to 5G should be challenged. Continuation of corporate and governmental policies that are not keeping up with today’s cyber risk do not bode well for a volumetric expansion of the attackable network and data surface of 5G networks. There is a crying need for coordinated efforts to achieve targeted expectations.

Two keys to winning the real “5G race”

The real “5G race” is whether the most important network of the 21st century will be sufficiently secure to realize its technological promises. Yes, speedy implementation is important, but security is paramount. To answer that overriding question requires new efforts by both business and government and a new relationship between the two.

The recommendations that follow are both important and not without cost. In normal times, such suggestions might be judged too much of a departure from traditional practices. These are not normal times, however. The outlook for a future that relies on 5G and other new digital pathways is cyber-defined. Our nation has moved into a new era of non-kinetic warfare and criminal activity by nation-states and their surrogates. This new reality justifies the following corporate and governmental actions.

Key #1: Companies must recognize and be held responsible for a new cyber duty of care

The first of this two-part proposal is the establishment of a rewards-based (as opposed to penalty-driven) incentive for companies to adhere to a “cyber duty of care.” Traditionally, common law established that those who provide products and services have a duty of care to identify and mitigate potential harms that could result. There needs to be a new corporate culture in which cyber risk is treated as an essential corporate duty and rewarded with appropriate incentives, whether in monetary, regulatory, or other forms. Such incentives would require adherence to a standard of cyber hygiene which, if met, would entitle the company to be treated differently than other non-complying entities. Such a cyber duty of care includes the following:

- Reversing chronic underinvestment in cyber risk reduction

Proactive cyber investment today is the exception rather than the rule. For public companies, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and others are driving change from the corporate board-level on down through management. A favorite entrance point for cyberattacks, however, remains the smaller companies, many of which are outside of the scope of these efforts. Unfortunately, the SEC’s efforts impact only the less than 10% of American companies that are publicly owned. At the very least, where companies have a role in critical infrastructure or provide a product or service that, if attacked, could imperil public safety, there must be the expectation that cybersecurity risks are being addressed proactively.2

- Implementation of machine learning and artificial intelligence protection

Cyberattacks on 5G will be software attacks; they must be countered with software protections. During a Brookings-convened discussion on 5G cybersecurity, one participant observed, “We’re fighting a software fight with people” whereas the attackers are machines. Such an approach was like “looking through soda straws at separate, discrete portions of the environment” at a time when a holistic approach and consistent visibility across the entire environment is needed. The speed and breadth of computer-driven cyberattacks requires the speed and breadth of computer-driven protections at all levels of the supply chain.

- Shifting from lag indicators of cyber-preparedness (post-attack) to leading indicators

A 2018 White House report found a “pervasive” underreporting of cyber events that “hampers the ability of all actors to respond effectively and immediately.” The 5G cyber realm needs to adopt leading indicator methodology to communicate cyber-preparedness between interdependent commercial companies and with government entities charged with oversight responsibilities. There are a number of good examples to pull from. Shared cyber risk assessments are increasingly a best practice for cyber-mature companies and their supply chain. Several accounting and insurance firms have developed lead metrics to inform cyber risk reduction investments and underwrite policies. The Department of Homeland Security has resiliency self-assessment standards to motivate long-term community disaster preparedness improvement.3 Such a model should be extended to the 5G cyber realm in order to shift oversight from lag indicators to lead indicators.

A regular program of engagement with boards and regulators using cybersecurity lead indicators will build trust, accelerate closing the 5G readiness gap and lead towards more constructive outcomes when cyber attackers do succeed. Underreporting of lag indicators, as highlighted in the 2018 White House report should be addressed, but with the primary purpose of closing the feedback loop, improving the quality of lead measures and the investment decision process they inform.

- Cybersecurity starts with the 5G networks themselves

While many of the large network providers building 5G are committing meaningful resources to cyber, small- and medium-sized wireless ISPs serving rural communities have been hard pressed to rationalize a robust cybersecurity program. Some of these companies have fewer than 10 employees and can’t afford a dedicated cyber security officer or a 24/7 cyber security operations center. Still, they will be offering 5G services and interconnecting with 5G networks. About one-third of these companies have ignored government warnings about the use of Huawei equipment and are now petitioning Congress to pay for their poor decisions and pay to replace the non-Chinese equipment. Any replacement must include the expectation that the companies will establish sufficient cybersecurity processes that sustain protections. All the networks that deliver 5G—whether big brand names, small local companies, wireless ISPs, or municipal broadband providers—must have proactive cyber protection programs.

- Insert security into the development and operations cycle

For many application developers, a core agile development tenet has been sprinting to deploy a minimum viable product, accepting risk, and committing to later providing consumer-feedback-driven upgrades once the product gains a following. Software companies and those providing innovative, software-based products and services are beginning to insert cybersecurity in the process as a design, deployment, and sustainment consideration for every new project. Such security by design should be a minimum duty of care across the commercial space for innovations in the emerging 5G environment.

- Best practices

The National Institute for Standards and Technology (NIST) Cybersecurity Framework has established five areas for best practice cybersecurity management that could become the basis of industry best practices: Identify, protect, detect, respond, and recover. For instance, NIST’s “identify” initiative focuses on determination of a company’s cyber universe, threats, and vulnerabilities in order to identify cyber risk reduction investments. While not limited only to the NIST framework, Congress should establish a cybersecurity standard of expected performance and accompanying incentives for its adoption by companies. While industry-developed best practices are a step in the right direction, they are only as strong as the weakest link in the industry and continue to place the burden on poorly informed consumers to know whether the best practices are being fulfilled. The Consumer Technology Association (CTA)—representing the $377 billion U.S. consumer technology industry—helped produce an anti-botnet guide that outlines best practices for device manufactures, but there is no way for a consumer to easily tell if it’s being followed.

“While industry-developed best practices are a step in the right direction, they are only as strong as the weakest link in the industry.”

Unfortunately, publication of optional cybersecurity best practices without full industry buy-in may be an attempt at responsible behavior and good public relations, but often do little to change the cyber risk landscape. While CTA has additionally published a useful buyer’s guide to explain cyber risk issues and improve household cyber hygiene, one wonders how many consumers of low-cost network connected technologies even know of its existence. Shifting cyber risk burdens to poorly informed consumers has limited utility. The 5G commercial sector needs to acknowledge the limits of consumer-based actions, own the residual risk, and work together with government oversight to assign cross-sector mitigation responsibilities.

Key #2: Government must establish a new cyber regulatory paradigm to reflect the new realities

Current procedural rules for government agencies were developed in an industrial environment in which innovation and change—let alone security threats—developed more slowly. The fast pace of digital innovation and threats requires a new approach to the business-government relationship.

- More effective regulatory cyber relationships with those regulated

Cybersecurity is hard, and we should not pretend otherwise. As presently structured, government is not in a good position to get ahead of the threat and determine detailed standards or compliance measures where the technology and adversary’s activities change so rapidly. A new cybersecurity regulatory paradigm should be developed that seeks to de-escalate the adversarial relationship that can develop between regulators and the companies they oversee. This would replace detailed compliance instructions left over from the industrial era with regular and fulsome cybersecurity engagements between the regulators and the providers at greatest risk as determined by criticality, scale (impact), or demonstrated problems (vulnerabilities) built around the cyber duty of care. It would be designed to reward sectors where participants have organized and are clearly investing ahead of failure to address risk factors.

Conversely, where sectors are ignoring cyber risk factors, graduated regulatory incentives can change corporate risk calculus to address consumer and community concerns. These activities would be afforded confidentiality and not be used by themselves to discover enforcement violations, but instead to help both regulators and the regulated better spot trends, best practices, and collectively and systematically improve their sector’s approach to cyber risk. DHS can have a supporting role for this, but at the end of the day, the balance between security, innovation, corporate means, and market factors is inherently regulatory. Absent the ability to impose a decision, government involvement can only be hortatory.

- Recognition of marketplace shortcomings

Economic forces drive corporate behavior. Of course, there are bottom-line-affecting costs associated with cybersecurity. Even when such costs are voluntarily incurred, however, their benefits can be undone by another company that doesn’t make the effort. The first of this paper’s two recommendations suggests what companies can do to exercise their cyber duty of care. History has shown, however, that the carrot accompanying such efforts often needs the persuasion of a standby stick. This is only fair to those companies that step up to their responsibility and should not be penalized in the marketplace by those that do not step up. A rewards-based policy would amplify the value of cyber duty of care participation, especially when others fall short. It would also provide forward-looking incentive for risk reduction and a more useful feedback loop when breaches invariably occur.

- Consumer transparency

Consumers have little awareness and no insight with which to make an informed market decision. The situation is analogous to the forces that resulted in the establishment of nutritional labeling for foods. Consumers should be given the tools with which to make informed decisions. “Nutritional labeling” about cyber risks or a cyber version of Underwriters Laboratories’ self-certification will help focus the attention of all parties on its importance.

- Inspection and certification of connected devices

For years, the FCC has overseen a program to certify that radio-signal-emitting devices do not interfere with authorized use of the nation’s airwaves. Whether cellphones, baby monitors, electronic power supplies, or Tickle Me Elmo, the FCC assures the design and assembly of transmitting devices are within standards. The industry then organizes underneath that construct to self-certify devices in a cost-effective means baked into their production and distribution processes. At the time of the 2016 DYN attack that took control of millions of video cameras, the authors proposed a similar regimen to review the cybersecurity of connected devices. If we protect our radio networks from harmful equipment, why do we not protect our 5G networks from cyber-vulnerable equipment?

- Contracts aren’t enough

Both the executive and legislative branches have focused on using government acquisition standards and pathfinder contracts to impose cybersecurity requirements where government contracts can compel commercial actions. This is an important, proven practice, but it can only go so far. Federal acquisition policies do not reach non-government suppliers that in an interconnected network can wreak havoc by simply connecting to the network. The majority of small and medium 5G network providers are not bound by any of these government contracts.

- Stimulate closure of 5G supply chain gaps

For years government review of mergers and acquisitions has typically failed to appreciate the potential negative impact on critical supply chains. Moving companies and processes offshore or to joint ventures with foreign ownership/control has created wholesale gaps in the supply of crucial 5G components and the absence of domestic procurement options. Country of origin/ownership concerns must become relevant to both the corporate calculus that led to offshoring purchase decisions as well as to the market conditions that led to the destruction of a national capability in the first place. 5G supply chain market analysis must be continuous with regular engagement between regulators, industry, and the executive and legislative branches to properly incentivize globally competitive domestic sourcing alternatives.

- Re-engage with international bodies

At present, the standards setting process for 5G is governed by the 3rd Generation Partnership Project (3GPP), an industry group that makes decisions by consensus based on input from its members, including Chinese 5G equipment companies. (Huawei reportedly made the most contributions to the 5G standard). The Obama FCC engaged directly with 3GPP to identify public safety and cybersecurity risk considerations applicable to the U.S. market. It additionally opened a notice of inquiry to ask the nation’s best technology brains how to implement cybersecurity risk reduction as part of the development and deployment cycle. The move was opposed by some industry associations and the Republican commissioners. Shortly after the beginning of the Trump administration, the new FCC cancelled the Obama FCC’s cyber initiatives.

There needs to be informed third-party oversight early in the 5G industry’s design and deployment cycle in order to prioritize cyber security. The nation, our communities and our citizens should—through their government—have some degree of agency in the process. The FCC and Commerce Department should participate in 3GPP and the U.S. feeder group as observer stakeholders. This will allow for earlier issue identification and the opportunity to submit concerns, without changing the basic governance of standards setting. The representatives of American citizens should have the option to escalate engagement on matters of national security and public safety concern.

Conclusion

It is an amazing turn of events when the U.S. Senate, currently led by Republicans, feels it necessary to introduce legislation instructing the Trump administration “to develop a strategy to ensure the security of next generation mobile telecommunications systems and infrastructure.” The 5G cybersecurity threat is a whole-of-the-nation peril. We should not be lulled into complacency because the newness of the network has masked the threat. We must not confuse 5G cybersecurity with international trade policy. Congress should not have to pass legislation instructing the Trump administration to act on 5G cybersecurity. The whole-of-the-nation peril requires a whole-of-the-economy and whole-of-the-government response built around the realities of the information age, not formulaic laissez faire political philosophy or the structures of the industrial age.

“People are going to be put at risk and possibly die as we increasingly connect life sustaining devices to the internet,” was the stark warning from one of the experts participating in a Brookings roundtable on 5G cybersecurity. This cold reality is because the internet’s connection to people and the things on which they depend will increasingly be through vulnerable 5G networks. It is an exposure that is exacerbated by a cyber cold war simmering below the surface of consumer consciousness.

Early generation cyberattacks targeted intellectual property, extortion, and hacked databases. Today, the stakes are even higher as nation-state actors and their proxies gain footholds in our nation’s critical infrastructure to create attack platforms lying in wait. Any rational risk-based assessment reveals that the favored adversary target is our commercial sector. Companies that provide critical network infrastructure or provide products or services connected to it represent the likely and potentially most dangerous enemy course of action in the ongoing cyber cold war.

“If you’re asking me if I think we’re at war, I think I’d say yes,” the former commandant of the Marine Corps, Gen. Robert Neller, told an audience in February. “We’re at war right now in cyberspace. … They’re pouring over the castle walls every day.” While our adversaries, no doubt, see positive outcomes for high-profile direct attack, they also are perfecting less-risky positive outcomes in a steady pace of low-level attacks intended to erode U.S. public confidence in our cyber critical infrastructure and the digital economy it underpins. The low-intensity cyber war is already ongoing as our adversaries risk very little in these attacks and stand to gain much.

Into this attack environment has come a software-based network built on a distributed architecture. With its software operations per se vulnerable, and a distributed topology that precludes the kind of centralized chokepoint afforded by earlier networks, 5G networks will be an invitation to attacks. Given that the cyber threat to the nation comes through commercial networks, devices, and applications, our 5G cyber focus must begin with the responsibilities of those companies involved in the new network, its devices, and applications. The cyber duty of care for those involved in 5G services is the beginning of such proactive responsibility.

“Yes, the “race” to 5G is on—but it is a race to secure our nation, our economy, and our citizens.”

At the same time, the federal government has its own responsibility to create incentives for 5G companies to focus on the cyber vulnerabilities they create. This is especially the case when there may be a corporate or marketplace lack of motivation to prioritize a maximum cyber effort. As outlined in this paper, this will necessitate replacing the rigid industrial-era relationship between government and business with more innovative and agile means of dealing with the shared problem.

Yes, the “race” to 5G is on—but it is a race to secure our nation, our economy, and our citizens.

The moment is now for a bipartisan call to action to not just address the current 5G exposures, but also to address the structural shortfalls that have allowed the cyber readiness gap to continue to grow. What got us here won’t get us to a secure 5G-enabled future.

Tom Wheeler was the 31st chair of the FCC from 2013 to 2017. Currently, he is a visiting fellow at the Brookings Institution. Rear Admiral David Simpson, USN (Ret.), was chief of the FCC’s Public Safety and Homeland Security Bureau during the same period. Currently, he is a professor at Virginia Tech’s Pamplin College of Business.

The Brookings Institution is a nonprofit organization devoted to independent research and policy solutions. Its mission is to conduct high-quality, independent research and, based on that research, to provide innovative, practical recommendations for policymakers and the public. The conclusions and recommendations of any Brookings publication are solely those of its author(s), and do not reflect the views of the Institution, its management, or its other scholars.

Microsoft provides general, unrestricted support to The Brookings Institution. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions posted in this piece are not influenced by any donation. Brookings recognizes that the value it provides is in its absolute commitment to quality, independence, and impact. Activities supported by its donors reflect this commitment.

-

Footnotes

- Captain Wayne P. Hughes, Jr., USN (Ret.), Fleet Tactics and Coastal Combat, 2nd ed., U.S. Naval Institute Press, 2000, pp.40-44

- Gordon, L.A., Loeb, M.P., Lucyshyn, W. and Zhou, L. (2015). Externalities and the Magnitude of Cyber Security Underinvestment by Private Sec tor Firms: A Modification of the Gordon-Loeb Model. Journal of Information Security, 6, 24-30. http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/jis.2015.61003

- While the authors do not want to understate the shortfalls associated with the NIMS self-assessment model and lack of federal engagement at the regional level to assess actual NIMS implementation, we do want to note that a decade in, NIMS has succeeded in establishing a common language and investment framework for long-term steady improvements to resiliency in over 10,000 jurisdictions across the country.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).