It’s often a death that acts as a catalyst in public health policy—particularly the death of a child. However, in the case of the humanitarian crisis at the southern border where people, particularly children, are dying, the government’s response has been one that does not seek to fix the problem; instead, it is potentially making it worse. In an August letter to Congress, a group of doctors recommended more stringent protocols in border facilities to prevent, detect, and treat influenza. They discuss three children who died in Customs and Border Protection (CBP) custody who were found to have died of complications from influenza.

Later in August, in response, CBP released a statement that it would continue its practice not to administer vaccinations in its holding facilities. It’s too complex, the agency claimed, and CBP holding is too short-term for them to consider adopting a vaccination program.

This decision is only the most recent manifestation of the U.S. government’s unwillingness to adapt to new realities and changing flows at the border. No longer dominated by able-bodied adults seeking work in the United States, the flow to the southern border now consists of families, unaccompanied children, and people traveling much further than from Mexico.

The journey to the southern border has always been a dangerous one, but these deaths show just how incredibly vulnerable the people are who try to immigrate to the United States. We can also see how the system is working to deter them in every way possible and help them in as few ways as possible—even with something as simple as administering a flu shot. This stance has already had terrible and very preventable consequences, and revisiting it is essential.

The perfect storm for a public health policy failure

The Trump administration’s policy choices and inadequate planning have elevated the risk of an outbreak of a communicable disease within detention facilities. Such an outbreak would have serious impacts on detainees, the staff within detainment facilities, and residents of the communities around detainment facilities. The administration must work to ensure that decision-making over vaccination policy stems from public health realities—not an inhumane and punitive ideology.

“The administration must work to ensure that decision-making over vaccination policy stems from public health realities—not an inhumane and punitive ideology.”

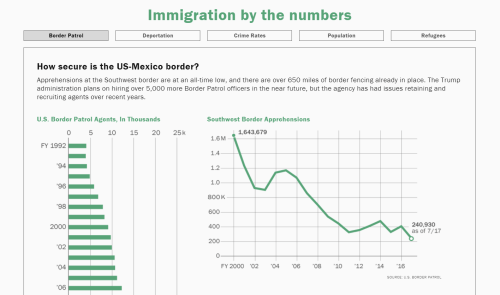

The Trump administration has opted to increase the enforcement of the nation’s immigration laws along the border and in the interior—a choice any administration is free to make. The result has been a significant increase in the apprehension of undocumented individuals within the United States and those seeking illegal entry into the country. In fiscal year 2019, CBP apprehended over 950,000 individuals—more than the previous two years combined. This increase in apprehension happened while the administration has failed to secure adequate funding increases within relevant agencies, put in place a system that can hire and train a workforce needed to administer such a policy change, or build infrastructure to house detainees in safe and humane conditions.

Instead, the administration has poured thousands of new detainees into already crowded facilities, further deepening the resource strain. This overcrowding exists for a population already vulnerable to health crises; most immigrants have traveled for hundreds or thousands of miles, come from poverty and political turmoil, and migrated with inadequate nutrition, insecurity, and poor living conditions—only to be detained within or prior to entry into the United States and be placed into similarly compromised conditions. The table below notes a series of risk factors for the outbreak of communicable diseases, and over the past few years, several of those have been found in detention facilities under CBP or Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

Even as detainees are held in substandard conditions by the federal government—without regular access to basic human needs, health care, and nutrition—the absence of policy planning from the Trump administration has exacerbated the problem by ensuring a lack of staff, in turn leading to large backlogs and extended processing times. Those individuals detained by immigration officials now face longer wait times to see their cases processed and, in some cases, see delays in processing because of health crises that they face due to these inadequate conditions.

“[T]he absence of policy planning from the Trump administration has exacerbated [immigration problems] by ensuring a lack of staff, in turn leading to large backlogs and extended processing times.”

Migrants are placed into situations equally conducive to outbreaks through the Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP), commonly referred to as Remain in Mexico. People who come from Central America awaiting asylum proceedings in Mexico live in conditions virtually as bad as those they would face in an overcrowded detention facility—and far worse, in terms of their vulnerability to crime. They experience the same instability, lack of reliable hygiene, and lack of access to good nutrition and health care. The result is an at-risk population, placed in conditions conducive to a communicable disease outbreak for extended periods of time.

To better understand the nexus of risks presented by the border crisis, and the opportunities for the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) to intervene and alleviate those risks, Hammer, et al.’s concept of “risk factor clusters” provides a useful rubric.1

Table 1: Evidence of risk factor clusters in U.S. immigration enforcement

| Risk factor | Evidence |

| WASH (Water, sanitation, and hygiene) |

“…most single adults had not had a shower in CBP custody despite several being held for as long as a month.” (OIG-19-51)

“For example, children at three of the five Border Patrol facilities we visited had no access to showers…” (OIG-19-51)

“Children told lawyers […] they’d gone weeks without bathing or a clean change of clothes.” (AP)

“’The kids had colds and were sick and said they didn’t have access to soap to wash their hands. It was an alcohol-based cleanser. Some kids who were detained for 2-3 weeks had only one or two opportunities to shower. One said they hadn’t showered in three weeks,’ [a Human Rights Watch staff member] said.” (CNN) |

| Overcrowding |

“However, at one facility, some single adults were held in standing room only conditions for a week and at another, some single adults were held more than a month in overcrowded cells.” (OIG-19-51)

“We are concerned that overcrowding and prolonged detention represent an immediate risk to the health and safety of DHS agents and officers, and to those detained.” (OIG-19-51) |

| Mass population displacement | According to UNHCR, by the end of 2019, over half a million people will be displaced from Central America. |

| Nutrition |

“While all facilities had infant formula, diapers, baby wipes, and juice and snacks for children, we observed that two facilities had not provided children access to hot meals — as is required by the TEDS standards — until the week we arrived. Instead, the children were fed sandwiches and snacks for their meals.” (OIG-19-51)

“Children told lawyers that they were fed oatmeal, a cookie and a sweetened drink in the morning, instant noodles for lunch and a burrito and cookie for dinner. There are no fruits or vegetables. They said they’d gone weeks without bathing or a clean change of clothes.” (AP) |

| Living conditions | “Florida resident Helen Perry, a nurse in the U.S. Army Reserve who joined a volunteer aid group headed to Matamoros on Labor Day weekend, told Reuters she saw families camped out in donated tents – each with between 5 to 10 people sleeping inside – a few dozen feet from the border.” (Reuters) |

| Infrastructure | “Migrants have been piling into the [Matamoros] camp at a rate of several dozen a day. With only two wooden shower stalls in the woods, less than 10 portable toilets and no cleaning supplies, the conditions are quickly deteriorating. Lack of running water and limited access to food have led the migrants to the river to bathe, fish and draw water; they use a wooded area nearby as a makeshift bathroom. When it rains, the migrants and all their belongings are quickly soaked.” (Texas Tribune) |

| Insecurity | Not applicable within detention facilities. |

| Health and public health services | Not applicable within detention facilities. |

| Environment | Not applicable within detention facilities. |

| Economy | Not applicable within detention facilities. |

| Humanitarian response | Not applicable within detention facilities. |

Because of the increased risks for an outbreak of disease like influenza—and the risks that disease can pose for vulnerable populations within detention facilities, for staff, and for those in the surrounding communities—the ideal solution would be for the government to protect public health by instituting a vaccine program, particularly for common diseases that require annual vaccinations. However, as noted above, DHS has stated that they will not vaccinate detainees, despite the public health risks.

Why a detainee vaccination program is essential

One of the most important reasons for instituting a vaccination program within immigration detention facilities is that it works. Vaccines have been demonstrated to lower the spread of diseases and significantly reduce the risk of outbreaks. What’s more, vaccine programs are cost-effective, particularly among children, the elderly, and at-risk populations. The average influenza vaccine, for instance, costs between $1.00 and $1.50 per dose, according to prices from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The cost of administering health care to an individual suffering from influenza is significantly higher for the average individual and for children, the elderly, and at-risk populations. The cost of a vaccine should not be the sole driver of decision-making around such a policy, but the reality is that cost-benefit analyses are a common tool in public health policymaking.

“Vaccines have been demonstrated to lower the spread of diseases and significantly reduce the risk of outbreaks. What’s more, vaccine programs are cost-effective, particularly among children, the elderly, and at-risk populations.”

So, what would such a program cost? A formal cost-benefit analysis will take into account a comprehensive set of factors, including individuals’ health histories, the precise conditions in which a population lives, the disease activity in that particular season, etc. But let’s lay out some basic numbers. Assume the average dose of influenza vaccine is $1.25. Recognizing that the transportation, storage, and administration of the vaccine incurs additional costs—though costs that decrease at the margin. Assume those costs increase the overall cost of the vaccine by 50%. Each vaccine would cost $1.88 per person. From October 2018–April 2019, CBP apprehended 532,052 people. This is very high compared with previous years, hence the overcrowding. The cost of vaccinating all detainees for that flu season would have been $1,000,258. That number is 0.002% of the overall budget of DHS, and 0.007% of the budget for CBP.

What’s more, the U.S. government recognizes the public health importance of vaccinating incoming immigrants, especially those coming from areas with inadequate health care access. There are comprehensive, mandatory vaccination programs for those receiving asylum as refugees and those seeking permanent residence within the U.S. Rather than extending that same policy logic to those detained within or forced to wait just outside of the United States, the Trump administration has opted to bear the risk.

“The cost of vaccinating all detainees for [the 2018-19] flu season would have been $1,000,258. That number is 0.002% of the overall budget of DHS, and 0.007% of the budget for CBP.”

For those diverted into MPP, illness can be the difference between surviving long enough in a migrant camp to attend their asylum hearings or having to return to their country of origin with a sick child. Anyone who misses a hearing will have their case decided in absentia. According to TRAC’s statistics on MPP, in absentia decisions effectively close every case.

The administration should recognize the humanitarian need for a vaccination policy for those held in immigration detention facilities. While those trying to enter the United States or those who are already undocumented within our borders have made choices or felt forced to do so, those vulnerable individuals did not choose to be held in federal government facilities that provide inadequate services, substandard conditions, and have extended adjudication wait times because of failed policy choices. States, too, should act. Although the vast majority of detainees are held in federal facilities outside of the regulatory power of state governments, states should implement laws and regulations that any individual held in the custody of ICE, CBP, or the Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Refugee Resettlement but housed in a state, local, or private facility must be vaccinated for certain diseases or shall be vaccinated by those state public health authorities.

Conclusion

The administration has been willing to declare a national emergency at America’s southern border while ignoring an actual public health emergency within government-run detention facilities—one largely of its own making. The U.S. government must act responsibly about the health risks within its own infrastructure and extend to detainees the same policies used for asylum recipients and those receiving permanent residency.

The authors would like to acknowledge Lena Burleson’s contributions to researching and editing this report.

The Brookings Institution is a nonprofit organization devoted to independent research and policy solutions. Its mission is to conduct high-quality, independent research and, based on that research, to provide innovative, practical recommendations for policymakers and the public. The conclusions and recommendations of any Brookings publication are solely those of its author(s), and do not reflect the views of the Institution, its management, or its other scholars.

-

Footnotes

- The authors spoke to experienced professionals in humanitarian response and looked at published papers about complex humanitarian emergencies to understand what factors created the risk of infectious disease outbreaks in crisis situations. Not all of them apply to every situation, but several risk factor clusters have been well-documented in border holding facilities, ICE detention, and on the ground in Mexican border cities where asylees have been forced to wait. All of these living situations in the immigration system are related—people are moved between them every day.