This report is part of the Series on Regulatory Process and Perspective and was produced by the Brookings Center on Regulation and Markets.

By now, it is obvious to everyone seeking to understand the United States’ response to the novel coronavirus (officially SARS-CoV-2) that there were massive failures of judgment and inaction in January, February, and even March of this year. While mistakes are inevitable in the face of such a massive and rapidly evolving domestic and global challenge, our federal government’s response compares unfavorably to a number of other countries, many of whom faced the virus before we did.

Although we will undoubtedly soon find ways to overcome our missteps, it will take years to fully reckon with the failures that contributed to our poor response. No doubt, sometime in 2020 or 2021, Congress will create a well-funded government commission to undertake an investigation similar to the 9-11 Commission or the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission. Such an investigation will need to grapple with insufficient preparation and capacity, poor leadership and coordination, slowness, and regulatory failures, among many other factors. In doing so, it ought to focus especially on those systemic failures that can be corrected so that they are much less likely to recur in the certain event of future pandemics, whether naturally occurring or deliberately caused.

A number of long-form journalistic pieces offer narrative accounts of what went wrong (including excellent pieces in the New York Times, Reuters, the Wall Street Journal, and The Atlantic). Here, we attempt to present an initial record of the federal government’s important official actions and communications over the past months, with a particular emphasis on the rules, regulation, and guidance related to the public health challenge. We do not claim comprehensiveness—rather, we seek to document new and notable developments and actions during the critical early period of the worldwide spread of the virus. Nor do we attempt to track the extensive actions meant to cope with the economic fallout of the virus. Following the timeline, we briefly outline four phases of crisis response and highlight some of the most important apparent failures.

timeline of federal government actions and communications

FIRST PHASE

From the first knowledge of the virus’s spread in Wuhan in early January through nearly the end of that month, the administration publicly treated the virus as a minor threat that was under control, at least domestically, and repeatedly assured the public that the risk to Americans was very low. However, by the middle of January, the virus had clearly spread beyond China, as cases were reported in Thailand, Japan, and South Korea, among other countries. On January 17, the CDC started screening at three U.S. airports those passengers who had been traveling in Wuhan, but by then the virus had already spread to countries other than China. By the end of the month, there were about 12,000 reported cases in China, growing rapidly by the day; at this point, the U.S. had a handful of confirmed cases, but there was almost certainly already significant community spread in the Seattle area.

Second Phase

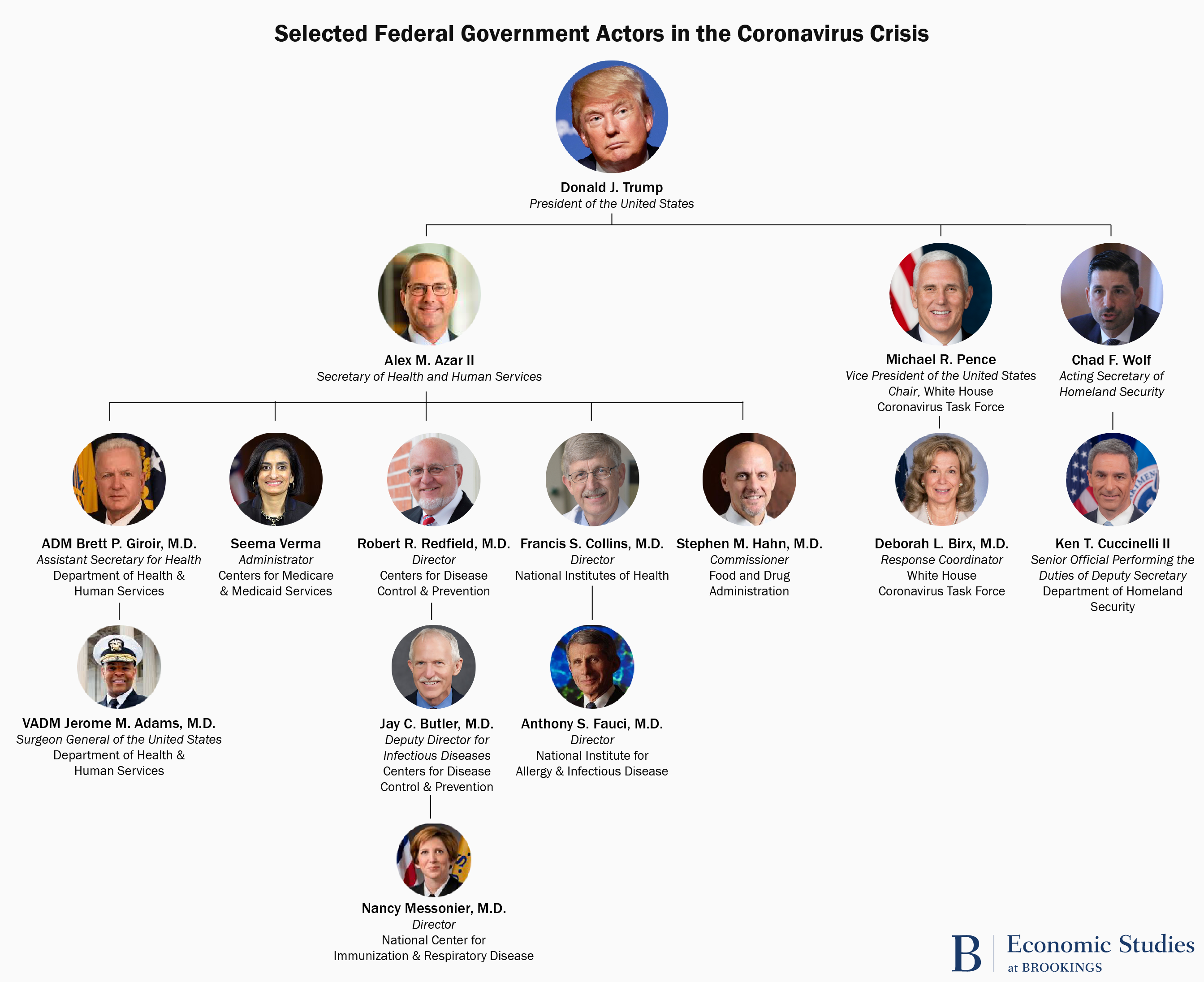

Beginning with the creation of the White House Coronavirus Task Force on January 27 (publicly announced on January 29) and the declaration of a public health emergency on January 31, the federal government began to put in motion the executive, legal, and regulatory pandemic response procedures already on the books. It also banned foreign nationals who had traveled in mainland China from entering the country.

Most critical for this second phase, it was clear early on that any effective response was going to depend on rapidly scaling our testing capacity. The virus genome was publicly available in mid-January, and the first tests were developed shortly thereafter. The World Health Organization (WHO) sent hundreds of thousands of tests to dozens of laboratories around the world by early February. But the administration and CDC decided to rely exclusively on domestically developed tests, apparently in keeping with past practice. The CDC developed its own test in early February, which was then distributed to labs. But, as became clear roughly a week later, one of the reagents in its kits proved to be faulty, which meant that most labs were unable to proceed using CDC-provided test kits.

Nevertheless, for at least two weeks after the problem became clear, alternative paths to testing were either neglected or stymied by existing regulations. Indeed, although the Emergency Use Authorizations required by the declaration of a public health emergency were meant to facilitate rapid testing, it soon became clear that their required procedures were actually significantly retarding the development of effective testing at scale. CDC was reassuring state and local officials that testing capacity was adequate in late February, although it was reported that fewer than 500 tests had been conducted at that point. (CDC’s own count, which includes its own tests plus those of U.S. public health labs, puts the total number of tests at the end of February at around 4,000.) Perversely, the failure to test at scale kept the publicly recognized number of cases low, which served as a justification for insisting that the existing testing regime was adequate.

This phase lasted through nearly all of February—a lost month during a critical period. As China and other countries took extreme measures to contain the spread of disease, the federal government and most state and local governments took few actions to disrupt normal economic and social life—indeed, some governments infamously discouraged their citizens from altering their behavior. By the end of the month, the United States had two dozen confirmed cases (artificially low because of the low levels of testing), China reportedly had about 80,000 cases, and Italy was already in the early stages of uncontrolled viral spread with nearly 2,000 reported cases.

Third phase

A third phase began in late February, when the CDC and FDA demonstrated a clear shift in their sense of urgency. Beginning with the CDC widening testing criteria on February 28 and the Food and Drug Administration allowing use of non-approved tests (with retroactive approval) on February 29, the federal government signaled that it had begun to recognize and correct for the flaws in its testing regime. Travel bans were extended to foreign nationals who had traveled in Iran. Federal officials worked more concertedly to promote private sector involvement in the crisis response, and Congress passed an $8.6 billion supplemental appropriation bill to promote vaccine and treatment research, emergency telehealth, and preparedness. Although testing was finally expanding during this phase, availability was still severely limited, in spite of administration insistence of adequacy.

Fourth Phase

The fourth phase, dating from President Trump’s nationally televised address on March 11 and his March 13 declaration of a national emergency, finally saw the federal government fully engage in its efforts to hasten mass testing, improve the availability of medical supplies, and encourage all Americans to radically alter their behavior in order to arrest the spread of the virus. Further travel restrictions were placed on foreign nationals who had traveled in continental Europe, and then in the United Kingdom and Ireland. Various emergency powers, including the Defense Production Act, were activated and then later employed. Commercial tests were approved quickly and mass testing finally became a reality—which, in turn, helped reveal the considerably advanced spread in the U.S. Over the month of March, confirmed cases in the United States increased at a rapid clip, passing 100 (3/5), then 1,000 (3/11), then 10,000 (3/18), and by the end of the month 100,000 (3/27), reflecting in part that our testing capacity had begun to catch up with reality on the ground.

The authors did not receive financial support from any firm or person for this article or from any firm or person with a financial or political interest in this article. They are currently not an officer, director, or board member of any organization with an interest in this article.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).