It started with an email from an unknown sender with the subject line, “Read this and be smart.”1

When the victim opened the email, she found sexually explicit photos of herself attached and information that detailed where she worked. Following that were details of her personal life: her husband and her three kids. And there was a demand.

The demand made this hack different: This computer intrusion was not about money. The perpetrator wanted a pornographic video of the victim. And if she did not send it within one day, he threatened to publish the images already in his possession, and “let [her] family know about [her] dark side.” If she contacted law enforcement, he promised he would publish the photos on the Internet too.

Later in the day, to underscore his seriousness, the hacker followed up with another email threatening the victim: “You have six hours.”2

This victim knew her correspondent only as [email protected], but the attacker turned out to be a talented 32-year-old proficient in multiple computer languages. Located in Santa Ana, California, his name was Luis Mijangos.3

On November 5, 2009, [email protected] sent an email to another woman with the subject line: “who hacked your account READ it!!!”4In the email, Mijangos attached a naked photo of the victim and told her “im [sic] in control of your computers right now.”5

Mijangos had other identities too: Some emails came from [email protected]; sometimes he was [email protected].6 According to court records in his federal criminal prosecution, Mijangos used at least 30 different screen names to avoid detection.7 But all emails came from the same IP address in Santa Ana.

Law enforcement authorities investigating the emails soon realized that the threatening communications were part of a larger series of crimes. Mijangos, they discovered, had tricked scores of women and teenage girls into downloading malware onto their computers. The malicious software he employed provided access to all files, photos, and videos on the infected computers.8 It allowed him to see everything typed on their keyboards.9 And it allowed him to, at will, turn on any web camera and microphone attached to the computer, a capability he used to watch, listen, and record his victims without their knowledge.10 He kept detailed files on many of his victims, at times gathering information for more than a month, and filling his files with information he could later use to manipulate his victims.11 Mijangos used a keylogger – a tool that allowed him to see everything typed on a computer – to track whether the victims told friends and family or law enforcement about his scheme.12 And if they did, he would then threaten them further, notifying them that he knew they had told someone. The malware Mijangos wrote was sophisticated, and he told federal authorities that he designed it specifically to be undetectable to antivirus programs.13

In some cases, he tricked victims into creating pornographic images and videos by assuming the online identity of the victims’ boyfriends.14 He then, according to court documents, “used [those] intimate images or videos of female victims he stole or captured to ‘sextort’ those victims, threatening to post those images or videos on the Internet unless the victims provided more.”15

Mijangos’s threats were not idle. In at least one case, he posted nude photos of a victim on the Myspace account of a friend of the victim, which Mijangos had also hacked, after she refused to comply with his demands.16

To make matters worse, Mijangos also used the computers he controlled to spread his malware further, propagating to the people in his victims’ address books instant messages that appeared to come from friends and thereby inducing new victims to download his malware.17

In all, federal investigators found more than 15,000 webcam-video captures, 900 audio recordings, and 13,000 screen captures on his computers.18 Mijangos possessed files associated with 129 computers and roughly 230 people.19 Of those, 44 of his victims were determined to be minors.20 His scheme reached as far away as New Zealand. The videos he surreptitiously recorded showed victims in various states of undress, getting out of the shower, and having sex with partners.21 In addition to the intimate material he seized from victims’ computers, federal authorities also found credit card and other online account information consistent with identity theft.22 He sometimes passed this information along to co-conspirators around the world.23

Mijangos’ actions constitute serial online sexual abuse—something, we shall argue, akin to virtual sexual assault. As the prosecutor said in the case, Mijangos “play[ed] psychological games with his victims”24 and “some of his victims thoroughly feared him and continued to be traumatized by his criminal conduct.”25 One victim reported feeling “terrorized” by Mijangos, saying that she did not leave her dorm room for a week after the episode.26 His victims reported signs of immense psychological stress, noting that they had “trouble concentrating, appetite change, increased school and family stress, lack of trust in others, and a desire to be alone.”27 At least one harbored a continuing fear that her attacker would “return.”28

Mijangos was arrested by the FBI in June 2010.29 He pled guilty to one count of computer hacking and one count of wiretapping.30

He was sentenced to six years imprisonment and is scheduled to be released next year.31

* * *

As bizarre as the Mijangos case may sound, his conduct turns out to be not all that unusual. We searched dockets and news stories for criminal cases in which one person used a computer network to extort another into producing pornography or engaging in sexual activity. We found nearly 80 such cases involving, by conservative estimates, more than 3,000 victims.

This is surely the tip of a very large iceberg. Prosecutors colloquially call this sort of crime “sextortion.” And while not all cases are as sophisticated as this one, a great many sextortion cases have taken place―in federal courts, in state courts, and internationally―over a relatively short span of time. Each involves an attacker who effectively invades the homes of sometimes large numbers of remote victims and demands the production of sexual activity from them. Sextortion cases involve what are effectively online, remote sexual assaults, sometimes over great distances, sometimes even crossing international borders, and sometimes―as with Mijangos―involving a great many victims.

We tend think of cybersecurity as a problem for governments, major corporations, and—at an individual level—for people with credit card numbers or identities to steal. The average teenage or young-adult Internet user, however, is the very softest of cybersecurity targets. Teenagers and young adults don’t use strong passwords or two-step verification, as a general rule. They often “sext” one another. They sometimes record pornographic or semi-pornographic images or videos of themselves. And they share material with other teenagers whose cyberdefense practices are even laxer than their own. Sextortion thus turns out to be quite easy to accomplish in a target-rich environment that often does not require more than malicious guile.

For the first time in the history of the world, the global connectivity of the Internet means that you don’t have to be in the same country as someone to sexually menace that person.

It is a great mistake, however, to confuse sextortion with consensual sexting or other online teenage flirtations. It is a crime of often unspeakable brutality.

It is also a crime that, as we shall show, does not currently exist in either federal law or the laws of the states. As defined in the Mijangos court documents, sextortion is “a form of extortion and/or blackmail” wherein “the item or service requested/demanded is the performance of a sexual act.”32 The crime takes a number of different forms, and it gets prosecuted under a number of different statutes. Sometimes it involves hacking people’s computers to acquire images then used to extort more. More often, it involves manipulation and trickery on social media. But at the core of the crime always lies the intersection of cybersecurity and sexual coercion. For the first time in the history of the world, the global connectivity of the Internet means that you don’t have to be in the same country as someone to sexually menace that person.

The problem of this new sex crime of the digital age, fueled by ubiquitous Internet connections and webcams, is almost entirely unstudied. Law enforcement authorities are well aware of it. Brock Nicholson, head of Homeland Security Investigations in Atlanta, Georgia, recently said of online sextoriton, “Predators used to stalk playgrounds. This is the new playground.”33

But while the FBI has issued numerous warnings about sextortion, the government publishes no data on the subject. Unlike its close cousin, the form of nonconsensual pornography known as “revenge porn,” the problem of sextortion has not received sustained press attention or action in numerous state legislatures, in part because with few exceptions, sextortion victims have chosen to remain anonymous, as the law in most jurisdictions permits.

The 78 cases we reviewed alone involve at least 1,397 victims, and this is undoubtedly just the tip of the iceberg.

But don’t let the problem’s invisibility fool you. The 78 cases we reviewed alone involve at least 1,397 victims, and this is undoubtedly just the tip of the iceberg. If the prosecutorial estimates in the various cases are to be believed, the number of actual victims probably ranges between 3,000 and 6,500―and, for reasons we explain below, may be much higher even than that. As the teenage child of one of the present authors put the matter, “You just can’t put a portable porn studio in the hands of every teenager in the country and not expect bad things to happen.”34

This paper represents an effort―to our knowledge the first―to study in depth and across jurisdictions the problems of sextortion. In it, we look at the methods used by perpetrators and the prosecutorial tools authorities have used to bring offenders to justice. We hope that by highlighting the scale and scope of the problem, and the brutality of these cases for the many victims they affect, to spur a close look at both state and federal laws under which these cases get prosecuted.

Our key findings include:

- Sextortion is dramatically understudied. While it’s an acknowledged problem both within law enforcement and among private advocates, no government agency publishes data on its prevalence; no private advocacy group does either. The subject lacks an academic literature. Aside from a few prosecutors and investigators who have devoted significant energy to the problem over time, and a few journalists who have written—often excellently—about individual cases, the problem has been largely ignored.

- Yet sextortion is surprisingly common. We identified 78 cases that met our definition of the crime—and a larger number that contained significant elements of the crime but that, for one reason or another, did not fully satisfy our criteria. These cases were prosecuted in 29 states and territories of the United States and three foreign jurisdictions.

- Sextortionists, like other perpetrators of sex crimes, tend to be prolific repeat players. Among the cases we studied, authorities identified at least 10 victims in 25 cases. In 13 cases, moreover, there were at least 20 identified victims. And in four cases, investigators identified more than 100 victims. The numbers get far worse if you consider prosecutorial estimates of the number of additional victims in each case, rather than the number of specifically identified victims. In 13 cases, prosecutors estimated that there were more than 100 victims; in two, prosecutors estimated that there had been “hundreds, if not thousands” of victims.

- Sextortion perpetrators are, in the cases we have seen, uniformly male. Victims, by contrast, vary. Virtually all of the adult victims in these cases are female, and adult sextortion therefore appears to be a species of violence against women. On the other hand, most sextortion victims in this sample are children, and a sizable percentage of the child victims turn out to be boys.

- There is no consistency in the prosecution of sextortion cases. Because no crime of sextortion exists, the cases proceed under a hodgepodge of state and federal laws. Some are prosecuted as child pornography cases. Some are prosecuted as hacking cases. Some are prosecuted as extortions. Some are prosecuted as stalkings. Conduct that seems remarkably similar to an outside observer produces actions under the most dimly-related of statutes.

- These cases thus also produce wild, and in in our judgment indefensible, disparities in sentencing. Many sextortionists, particularly those who prey on minors, receive lengthy sentences under child pornography laws. On the other hand, others—like Mijangos—receive sentences dramatically lighter than they would get for multiple physical attacks on even a fraction of the number of people they are accused of victimizing. In our sample, one perpetrator received only three years in prison for victimizing up to 22 young boys.35 Another received only 30 months for a case in which federal prosecutors identified 15 separate victims.36

- Sentencing is particularly light in one of two key circumstances: (1) when all victims are adults and federal prosecutors thus do not have recourse to the child pornography statutes, or (2) in cases prosecuted at the state level.

- Sextortion is brutal. This is not a matter of playful consensual sexting—a subject that has received ample attention from a shocked press. Sextortion, rather, is a form of sexual exploitation, coercion, and violence, often but not always of children. In many cases, the perpetrators seem to take pleasure in their victims’ pleading and protestations that they are scared and underage. In multiple cases we have reviewed, victims contemplate, threaten, or even attempt suicide—sometimes to the apparent pleasure of their tormentors.37 At least two cases involve either a father or stepfather tormenting children living in his house.38 Some of the victims are very young. And the impacts on victims can be severe and likely lasting. Many cases result, after all, in images permanently on the Internet on multiple child pornography sites following extended periods of coercion.

- Certain jurisdictions have seen a disproportionate number of sextortion cases. This almost certainly reflects devoted investigators and prosecutors in those locales, and not a higher incidence of the offense. Rather, our data suggest that sextortion is taking place anywhere social media penetration is ubiquitous.

The paper proceeds in several distinct parts. We begin with a literature review of the limited existing scholarship and data on sextortion. We then outline our methodology for collecting and analyzing data for the present study. We then offer a working definition of sextortion. In the subsequent section, we provide a sketch of the aggregate statistics revealed by our data concerning the scope of the sextortion problem, and we examine the statutes used and sentences delivered in federal and state sextortion cases. We then turn to detailing several specific case studies in sextortion. In our last empirical section, we look briefly at the victim impact of these crimes. Finally, we offer several recommendations for policymakers, law enforcement, parents, teachers, and victims.

We offer more detailed legislative recommendations in a separate paper, “Closing the Sextortion Sentencing Gap: A Legislative Proposal.”39

An understudied problem

Sextortion is remarkably understudied. Despite the rash of sextortion cases, some of them reasonably prominent, press attention to the issue has been modest, particularly in comparison to the dramatic attention devoted to issues of online bullying, child pornography generally, and revenge porn. While federal law enforcement has responded vigorously to individual cases around the country, a broader policy discussion has not followed. Most people, we suspect, have never heard of sextortion.

The term “sextortion” is not new. It began popping up in news coverage of incidents of sexual extortion involving online sexual exchanges with relative frequency beginning in 2010,40 though we found one use of the term dating back to 1950.41 Prosecutors use the term routinely in public statements to describe a certain type of case.42

Still, there has been no serious academic research surrounding sextortion. There have been no studies examining the most basic questions surrounding the problem: How common are these cases? What are the basic elements that characterize them? Are our laws adequate for the investigation and prosecution of sextortion cases?

For its part, the press has tended to report on individual cases, not on the phenomenon more broadly. Mentions of the larger problem tend to be passing ones. The New York Times, for example, recently ran a short piece in its “Sunday Review” section, outlining all types of scams that those looking for love on the Internet might encounter, including sextortion.43 Another Times article on the anonymous messaging app Kik noted that law enforcement commonly comes across the app in connection with sextortion cases.44 In these Times pieces, as with most instances, the mention of sextortion is fleeting.

GQ magazine has run two feature-length stories on sextortion, both focused on individual cases. In 2009, the magazine covered the story of Anthony Stancl, a troubled and bullied student at New Berlin Eisenhower high school in Wisconsin, who tricked fellow male students into sending him sexually explicit photos and videos as both a form of sexual gratification and also social revenge.45 Though the title of the GQ piece about Stancl references sextortion, the piece does not explore the subject beyond Stancl’s own case.

In 2011, GQ readers also learned of Mijangos in an article that does highlight the unique qualities of sextortion. That article explained that “[d]espite billions spent on technology that lets us broadcast our daily lives, all it takes is one guy, a self-taught hacker with no college degree, to turn that power against us.”46 A number of media outlets have done brief pieces on the problem.47

The Digital Citizens Alliance touched on sextortion tangentially as part of a report on remote access trojans (RATs). The report, among other things, demonstrated that RATs like the one used by Mijangos are easily accessible and quite affordable. On one hacker website, the authors found an advertisement for access to computers that belong to girls for $5 each; access to a boy’s computer sold for less, only $1 each. The report also notes thousands of tutorials on YouTube, instructing hackers on the best techniques for slaving a device; other videos appear to show off an individual hacker’s exploits, displaying videos of victims from their own webcams. Yet this report, published in 2015, focused on the cybersecurity problem of RATs broadly, and less on the exploitations at play in sextortion cases.48

Government attention has likewise been spotty. The Justice Department’s in-house bulletin for prosecutors has specifically addressed the sextortion phenomenon only once, in 2011, and then in a brief, five-page article on charging options for cases involving underage victims only.49 The Federal Bureau of Investigation cautioned parents and their children about the sextortion threat in a 2012 advisory.50 The following year, the Bureau’s then-director touched on sextortion in a stray paragraph in congressional testimony that canvassed the Bureau’s various law enforcement and other activities.51 In 2015, the FBI once again warned parents and children following the conviction of one Lucas Michael Chansler (see case studies below), this time calling on the public for more information about Chansler’s crimes,52 and releasing a video explaining how sextortion occurs and how parents should talk to their children about it.53 As part of the same release, the FBI also produced a short, one-minute radio briefing on the “growing number of reports of sextortion.”54 A separate sextortion fact sheet, released at the same time, provided more information on how perpetrators carry out their crimes, and ways for parents and children to protect themselves from those who would try to sextort them.55

Yet there has never been a congressional hearing on sextortion as a free-standing issue, and neither current nor proposed legislation so much as mentions the phenomenon. To the extent sextortion is on officialdom’s radar at all, it appears only as part and parcel of a bigger struggle to beat back online sex offenses more generally.

The scholarship has trended along similar lines. Some legal scholarship has alluded to sextortion, but only in passing.56 Legal academics have noted the phenomenon in the context of computer crimes more broadly, but have not concentrated on sextortion as a focus of study.

Take for example Dayton Law Professor Susan Brenner’s book “Cybercrime and the Law,” which dedicated only four of its 219 pages to the crime of sextortion. After noting that cyber sexual extortion is a new but rising phenomenon and naming a few recent cases, Brenner concludes that extortion statutes wherein the target’s property is presumed to have value in the “traditional, financial sense” may present difficulties for prosecutors in these cases. She suggests prosecutors may be successful by “(1) adopting new, sextortion-specific statutes or (2) revising existing extortion statutes so they encompass the type of harm inflicted in sextortion cases.”57 Danielle Keats Citron’s excellent book, “Hate Crimes in Cyberspace,” contains extensive discussion of revenge porn and virtually no discussion of sextortion.58

Nor are data, either official or private, readily available. We sought data on sextortion cases from the Bureau of Justice Statistics, which informed us that they “are not able to separate out” sextortion cases from other types of cases, as “federal data is based on statute and does not provide the detail needed to identify these offenses.”59 We also sought data from the FBI; despite the Bureau’s warnings on the subject, it could provide only a link to a webpage describing the Bureau’s Violent Crimes Against Children (VCAC) program.60 The Department of Justice was able to flag eight specific sextortion cases but noted that this was a “sampling” because “the department does not have a data-tracking category for sextortion.”61

We also sought data from activist organizations aware of and concerned about the problem.

We contacted the Cyber Civil Rights Initiative,62 the Cyber Civil Rights Legal Project,63 the Family Online Safety Institute,64 Thorn,65 and the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (NCMEC),66 none of which could provide data on the prevalence of sextortion cases nationally. The NCMEC has published a limited set of data culled from its CyberTipline, which it reports in part as follows:

- 78 percent of the incidents involved female children and 12 percent involved male children (In 10 percent of incidents, child gender could not be determined);

- The average age at the time of the incident was approximately 15 years old, despite a wider age-range for female children (eight-17 years old) compared to male children (11-17 years old); and

- In 22 percent of the reports, the reporter mentioned being suspicious of, or knowing that, multiple children were targeted by the same offender.

…

Based on the information known by the CyberTipline reporter, sextortion appears to have occurred with one of three primary objectives (In 12 percent of reports, the objective could not be determined):

- To acquire additional, and often increasingly more explicit, sexual content (photos/videos) of the child (76 percent)

- To obtain money from the child (six percent)

- To have sex with the child (six percent)

…

Sextortion most commonly occurred via phone/tablet messaging apps, social networking sites, and during video chats.

- In 41 percent of reports, it was suspected or known that multiple online platforms were involved in facilitating communication between the offender and child. These reports seemed to indicate a pattern whereby the offender would intentionally and systematically move the communication with the child from one online platform type to another.

- Commonly, the offender would approach the child on a social networking site and then attempt to move the communication to anonymous messaging apps or video chats where he/she would obtain sexually explicit content from the child. The child would then be threatened to have this content posted online, particularly on social media sites where their family and friends would see, if the child did not do what the offender wanted.67

These data, though useful and illuminating and broadly consistent with our own findings, are necessarily limited. Because they are only based on victim reporting, there is no information about subsequent prosecutions, investigative findings, or critically, victims other than ones who initially reported the offenses. That turns out to be a fateful omission.

Our point is not to criticize any of these organizations, or government agencies, for the lack of data on the subject. The problem of sextortion is, in fact, new. It remains relatively undefined. And at least with respect to the activist groups, it is a perfectly reasonable approach to focus on revenge porn first and on the problem of non-consensual pornography—of which sextortion is just one species—more generally. The result, however, is a certain gap in our understanding of this new form of crime. How big a problem is it really? How many people does it affect? And how should we define it? This paper represents a systematic effort to examine these problems.

Methods

Because of the disaggregated nature of the data we sought, the breadth of the problem, and the numerous criminal statutes available for possible prosecutorial use, we began with a systematic search of media on sextortion. Using LexisNexis, we searched media databases in all 50 states and the District of Columbia for keywords related to sextortion. We used the following keywords: “Sextort,” “Sextortion,” “Cyber Sextortion,” “Cyber Sexual Extortion,” “Cyber Sexual Exploitation,” “Online Sexual Extortion,” “Online Sexual Exploitation,” “Non-consensual Pornography,” and “Nonconsensual Pornography.” Using the same keywords, we then also searched WestLaw, looking for legal opinions involving sextortion.

The data we report here reflect our best sense of the sextortion landscape as of April 18, 2016.

We then read all media results that our searches of LexisNexis returned, selecting those cases from articles that fit the parameters we set for sextortion cases (described below). We identified 78 cases, 63 of them federal from 39 different judicial districts, 12 of them from the state courts of eight states, and three of them international cases from Israel, Mexico, and the Netherlands. In some instances, prosecutors we contacted made us aware of other cases. In other instances, the cases themselves cited earlier sextortion cases. As we progressed, a number of news stories made us aware of additional cases that arose after our searches took place.

For federal cases, we used both the Public Access to Court Electronic Records (PACER) service and proprietary online databases to gather the warrant applications, complaints, indictments, plea agreements, and judgments for the individual cases, as available, as well as other relevant documents that describe the conduct at issue in the cases. For state and international cases, we acquired original court documents where possible, but both for language and document-availability reasons, we also relied to a considerable degree on press accounts.

We examined each case to discern the number of clearly-identified (generally not by name) victims, the maximum number of victims estimated by prosecutors, the ages and genders of the victims, the number of states and countries involved in the offense pattern, and the sentence given the defendant (if any). We also tracked certain common elements of sextortion cases, both those charged and those pled or convicted; specifically, we identified the following recurrent elements in all cases in which they arose:

- computer hacking;

- manipulation of victims using social media (catfishing);

- interstate victimization;

- international victimization; and

- demand for in-person sexual activity.

For those cases prosecuted federally, we also looked specifically at the criminal offenses charged in each case, as well as those to which the defendant either pled guilty or was convicted.

The data we report here reflect our best sense of the sextortion landscape as of April 18, 2016. This report reflects neither developments within cases after that date nor new cases that have arisen since that date.

We are confident that this dataset is not complete. That is, there are sextortion cases both domestically and overseas, probably many of them, that we have not identified. We are even more confident that an enormous number of victims have not reported acts that would warrant aggressive investigation and prosecution along the lines of the cases we have found. We have identified the cases discussed in this study, in other words, not as illustrating the totality of the sextortion problem but as a significant and illustrative sample of it. We do not purport to know if it represents the bulk of the cases that have been prosecuted or not. We believe, however, that the prosecuted cases, like other forms of sexual assault, likely reflect a tiny percentage of the unprosecuted ones, meaning that we should understand online sextortion as a feature of life on the Internet for large numbers of vulnerable members of society.

Finally, one additional methodological note: For purposes of this study, we have taken prosecutorial allegations in many instances as true. Each of these cases involves an adjudication, and defendants are entitled to a presumption of innocence in the absence of proof beyond a reasonable doubt. We are not, however, an adjudicative body. We are, rather, looking to understand empirically the scope and depth of a social problem. As such, conduct that the FBI or prosecutors believe has taken place but for which a defendant has not been convicted may be just as interesting as that conduct which has generated a conviction. This point is especially important with respect to estimates as to the number of victims in different cases and to conduct charged but dropped in the context of plea agreements.

A working definition of sextortion

Legally speaking, there’s no such thing as sextortion. The word is a kind a prosecutorial slang for a class of obviously criminal conduct that does not in reality correspond neatly with any known criminal offense. Sextortion cases are sometimes prosecuted under child pornography laws, sometimes as computer intrusions, sometimes as stalkings, and sometimes as extortions. The term “sextortion” lacks a precise definition of its own, much less clear elements of the sort that arise out of legislative definition.

Legally speaking, there’s no such thing as sextortion. The word is a kind a prosecutorial slang for a class of obviously criminal conduct that does not in reality correspond neatly with any known criminal offense.

Still, at a high level of altitude, the conduct is easy enough to describe: sextortion is old-fashioned extortion or blackmail, carried out over a computer network, involving some threat—generally but not always a threat to release sexually-explicit images of the victim—if the victim does not engage in some form of further sexual activity.

By defining sextortion in this fashion, it is important to understand that we are excluding a variety of closely-related coercive activities that may also warrant more attention than they have received. For example, it is possible for something like sextortion to take place entirely offline; indeed, sexual extortion has taken place as long as people have had the power to demand sex from one another on threat of doing each other harm. We have not included any cases where conduct takes place solely in the offline world, however, on the theory both that this is an old problem that the law has had many generations to address and that it does not pose the same inter-jurisdictional and cybersecurity problems as do the same activities online. When we say “sextortion,” therefore, we are talking only about online sexual extortion. None of this is to diminish the horrifying extortions by which, for example, many pimps keep women in forms of sexual slavery.

Similarly, in the course of our research, we have discovered a number of cases—including several celebrated “revenge porn” cases—that have significant elements of sextortion and in which the threat of exposure of sexually-explicit material is used to extort money, but in which sexual activity itself is not demanded of the victim.68 In online sexually-oriented extortion, it is possible for a perpetrator to use the release of sexual images or videos as a threat against the victim; the production of sexual images or videos can also be the demand; most commonly, both take place at once. That is, the perpetrator uses the threat of the release of material to coerce the production of more material.

A related but distinct problem is that of online scams that extort money from individuals after they have engaged in anonymous online sexual video chatting—for example over Skype. One such syndicate in the Philippines was busted in 2015. Following a tip, Philippine police arrested 58 people and seized 250 computers in seven areas across the country. Police said the extortionists acquired hundreds of victims in Australia, Singapore, Hong Kong, the United States, and the United Kingdom over the course of three to four years. The group found and friended victims over various social media sites, inviting them to engage in cybersex. After surreptitiously filming the chats, the group would then demand up to $2,000 in exchange for not publicly posting the material. The national police chief of the Philippines compared the group to a call center, where employees sit in rows of cubicles luring in foreign victims. The extortion ring was broken up only after its activity led to the suicide of one 17-year-old boy located in Scotland.69

While these cases, and others like them, can be extremely severe and present their own cybersecurity and privacy problems, we have excluded from this analysis all cases in which sexual activity was not demanded of the victim. If a perpetrator threatens a victim with exposure of sexually-explicit videos unless she pays him money, we have not included that in our sample unless the perpetrator also demands the production of further sexual images or videos.

The reason for this decision is that the primary phenomenon we seek to define here is the remote coercion of sex. The remote coercion of money using sexual images is not a new problem, though the Internet has certainly made it worse. The ability of a person to force someone halfway around the world to engage in sexual activity, by contrast, is a new form of digital abuse that was unthinkable only a few years ago. The ability of a single perpetrator to exploit hundreds, or even thousands, of victims around the world was particularly beyond our collective imaginations.

We have thus proposed a relatively narrow definition that excludes a considerable body of related criminal activity in an effort to focus attention on what is new here.

The data in aggregate

We have included in this analysis a total of 78 cases70 in 52 different jurisdictions,71 29 states or territories,72 and three foreign countries.

Every single perpetrator in the cases we examined is male.

Fifty-five of those cases (71 percent) involve only minor victims.73 An additional 14 (18 percent), by contrast, involve a mix of minor victims and adult victims.74 In nine cases (12 percent), all identified victims were adults.75

Every single perpetrator in the cases we examined is male. The vast majority of the victims, by contrast, are female. Among the adult victims, nearly all are female.76 The picture is more complicated among the child victims, where a significant minority of victims is male. In 13 cases (17 percent) involving minor victims, all identified victims in court documents are male.77 In an additional eight cases (10 percent), the victims include both males and females.78 Several truly brutal cases focus on young boys. So it’s a mistake to think of sextortion as purely a problem of violence against women. There is clearly a problem with respect to boys as well.

The length of a given perpetrator’s sentence tends to turn less on the number of victims or the brutality of the conduct involved in the case than on whether the victims are minors or adults. The reason is that federal child pornography laws carry particularly stiff sentences, far stiffer than those at issue with stalking, extortion, or computer intrusion laws. The result is that of those cases that involved minor victims and did not produce a life sentence, the sentencing range varied from seven months to 139 years imprisonment, with a median of 288 months (24 years) and a mean sentence of 369 months (31 years). Cases that involved only adult victims, by contrast, involved sentencing ranges from one month to 6.5 years imprisonment, a median sentence of only 40 months and a mean sentence of 38 months.

By far, the most common feature of sextortion cases is social media manipulation, in which the perpetrator tricks the victim into sending him the compromising pictures he then uses to extort more. Social media manipulation of some kind is present in the overwhelming majority of cases. Fully 65 cases (83 percent) involve some form of social media manipulation.79 Also known as “catfishing,” this behavior is even more common when the victim is a minor, with some form of social media manipulation featuring in 91 percent of the cases involving minors.80 Only three cases with only adult victims, by contrast, involved catfishing.81 Alternatively, some form of computer hacking was involved in 43 percent of cases with adult victims,82 but only nine percent of cases only involving only minor victims.83 Hacking featured in 15 cases (19 percent) total.84

By far, the most common feature of sextortion cases is social media manipulation

In many of the cases involving catfishing, the defendant used information he had somehow discovered about the victim to make his catfishing more effective. In one case, the information in question was obtained by hacking the victim’s computer.85 In at least one other case, the defendant looked up information available online.86 In another, the defendant worked as a camp counselor over the summer and accumulated information about campers over the course of his job—and then later used that info to catfish and blackmail them.87 Similarly, the criminal complaint in one case alleges that the defendant used personal information he knew about his victims from his offline interactions with them to make his threats more effective.88

A majority of the cases we examined overtly crossed state lines, sometimes the lines of many states. Forty nine cases (63 percent) involved significant interstate elements: the perpetrator, for example, victimizing people in other states.89 At least six cases involved more than ten jurisdictions, either foreign or domestic.90 Seven additional cases involved more than five jurisdictions.91

The same cybersecurity vulnerabilities that are making our corporations and government agencies ripe for cyber exploitations from foreign intelligence agencies and hackers are making teenagers and young adults ripe for highly-remote sexual exploitations.

A surprising number of cases cross international borders as well. Sixteen cases (21 percent) involve a perpetrator victimizing at least one person in a country other than that in which he is himself residing.92 This finding seems particularly challenging. It used to be impossible to sexually assault someone in a different country. That is no longer true. The same cybersecurity vulnerabilities that are making our corporations and government agencies ripe for cyber exploitations from foreign intelligence agencies and hackers are making teenagers and young adults ripe for highly-remote sexual exploitations.

Some cases manage to leap out of the online world and involve abuse in the physical world. In 13 cases (17 percent) perpetrators demanded actual in-person sexual activity from victims, not merely the production of pornographic materials.93 This category of case hints at one of the fault lines in sextortion cases. The majority of sextortionists are after targets of opportunity on social media. Some sextortion cases, by contrast, are highly-targeted cases of intimate abuse: a former boyfriend who can’t let go and goes after his ex-girlfriend’s daughter,94 a father bent on molesting his daughter,95 or some other person with a pathological obsession with a particular victim.96 These cases tend to look more like stalking—and are often prosecuted as such. They tend to involve smaller numbers of victims. But they are also far likelier to involve physical abuse of those victims. In some of these cases, sextortion is only a part of a far larger pattern of abuse.

Calculating the total number of victims in these cases is impossible. The cases cumulatively identify 1,397 victims, but these are only the victims counted by authorities in charging or alleging specific conduct against a particular defendant. For example, if prosecutors included a specific reference to a particular sextortion victim in a charging document, a complaint, or a plea agreement, or if a sentencing memo says that a particular number of victims has been identified, this victim—or this number of victims—will be included in this total figure.

This way of counting, however, grossly undercounts the true number of victims. In many cases, prosecutors do not charge a defendant with every instance of sextortion of which they have reason to believe him guilty; they charge, rather, only conduct related to those victims where the evidence is most developed. Along the way, they sometimes mention a much larger figure of other cases in which they believe the same perpetrator was involved.

The disparities between the number of identified victims and the number estimated can be extreme. For example, in the case of Brian Caputo—a California man accused in federal court of posing as a teenage girl on social media to trick real teenage girls into sending him explicit pictures—prosecutors identified “at least eight possible minor victims.” On the other hand, in the same document, they say that they have found 843 emails in which “almost every e-mail either contained child pornography or was [Caputo] communicating with possible other unidentified victims.”97 Similarly, in the particularly sinister case of Richard Leon Finkbiner (detailed below), prosecutors identified only thirteen victims, but they made clear that those victims stood in for “hundreds, if not thousands, of other minors and adults all over the world” whom Finkbiner also sextorted.98 In some cases, the best prosecutorial estimates of the total number of victims are quite vague. The government frequently describes “numerous” victims, for example; in some cases it refers to “hundreds” or “more than 100” or some such minimum round number. By contrast, in some cases, investigators seem to have gone through a great deal of trouble to identify every victim they could. All of this makes any effort to estimate the total size of the victim population necessarily a back-of-the-envelope sort of calculation.

Still, it is possible in very round terms to give a sense of the magnitude of the victim population. If we take the list of prosecutorial estimates of the likely number of victims in each case, and we make a series of different assumptions about what certain terms suggest on average, we can come up with various estimates.99

A conservative approach would be to assume that when prosecutors describe a given sextortionist as having “numerous” victims, “numerous” will work out on average to around 20, that “hundreds” should be interpreted conservatively to mean 100, and that we should take the lowest figure in any range (meaning that a phrase like “between 100 and 150” should mean 100). Tabulated this way, the total victim court comes out to be around 3,200.

A more aggressive approach would be to assume that when prosecutors are only dealing with 20 victims, they tend to identify them and count them, and therefore phrases like “numerous” should mean something more like 50. Similarly, “hundreds” should refer to at least 200, and more than X should refer to something close to 150 percent of X than to X itself. In this approach, we take in any range of numbers the mean between the two poles. The phrase “at least hundreds and possibly thousands,” meanwhile, should imply something more like 750 than 100. Using this method of tabulation, the figure works out to be more than 5,200.

Even this approach, however, may involve a substantial undercount. In many cases, prosecutors do not even attempt an accounting of the total number of victims. They merely identify a few victims and prosecute based on those few, leaving the rest uncounted. There are thus a bunch of cases that are clearly not intimate abuse cases—say stalkings of individuals, which are highly targeted at those individuals—but give every indication, rather, of being more indiscriminate. Yet these 28 cases identify, like the intimate abuse cases, only one or two victims and lack a high-end estimate as to the number of victims. We think this is likely not because the number of identified victims is, in fact, equal to the total number of victims but—in most cases—because prosecutors did not bother to include estimates in their pleadings or because investigators did not bother to count other possible victims. To compensate for this, we examined the average disparity between the high-end victim estimate and the number of identified victims in those cases in which a high-end estimate does exist, using the more aggressive assumptions in our second model. In those cases, the high-end victim estimate averages to 4.6 times the number of identified victims. Using this multiplier for the set of 28, we estimate that a reasonable guess as to the total number of victims may include up to an additional 1,500 people.

Put simply, we think a reasonable estimate of total victims in these cases will run anywhere from about 3,000 to about 6,500.

We think a reasonable estimate of total victims in these cases will run anywhere from about 3,000 to about 6,500.

There’s at least one additional complicating factor. A single pair of sextortionists, the FBI has estimated, may have as many as 3,800 victims between them. This estimate does not appear in the court documents associated with their cases, which we discuss below. But the FBI has stated it publicly elsewhere.100 If that figure is correct, the entire range—calculated by whatever means and with whatever assumptions—needs to be shifted upward by nearly several thousand victims.

Prosecuting sextortion

One of the most interesting features of sextortion cases is the diversity of statutes under which authorities prosecute them. As we noted above, sextortion does not exist in federal or state law as a crime of its own. So sextortionate patterns of conduct can plausibly implicate any number of criminal statutes, which carry very different penalties and elements.

In the federal system, at least, the workhorse statute is 18 USC § 2251, which prohibits sexual exploitation of children. Prosecutors charged under this law in 43 of the cases under study here (55 percent).101 In particular, subsection § 2251(a) does a great deal of heavy lifting for prosecutors. Under that section, “Any person who employs, uses, persuades, induces, entices, or coerces any minor to engage in . . . any sexually explicit conduct for the purpose of producing any visual depiction of such conduct” is subject to a mandatory minimum sentence of 15 years in prison.102

More generally, the child pornography laws provide powerful tools of choice for prosecutors, at least in the cases in which minor victims are involved. Section § 2252 of Title 18, which relates to materials associated with the sexual exploitation of children, can be used to prosecute both receipt and distribution of child pornography and possession of it; charges under this section show up in 28 cases (36 percent).103 Seventeen cases (22 percent) also contain charges under the adjacent section § 2252A, which is a parallel law related to child pornography in particular.104 And 18 USC § 2422(b), which forbids coercion or enticement of a minor to engage in illegal sexual activity, shows up in 19 cases (24 percent).105 Where they are available, the child pornography laws do clearly give prosecutors the tools they need, owing to the stiff sentences they mete out.

The trouble is that not all sextortionists prey on children, and where none of the victims involved in the conduct charged is a minor, the cases fall into something of a statutory lacuna. After all, without touching someone or issuing a threat of force, it is not possible to violate the aggravated sexual abuse law (18 USC § 2241), which only applies in any event in the special maritime or territorial jurisdiction of the United States or in a prison facility. (That same jurisdictional limit applies to the lesser crime of sexual abuse, 18 USC § 2242, and other federal sex crimes statutes.) In other words, absent a child victim, there’s no obvious on-point federal law that covers the sexual elements of sextortion.

In other words, absent a child victim, there’s no obvious on-point federal law that covers the sexual elements of sextortion.

The result is a frequent prosecutorial reliance on the federal interstate extortion statute (18 USC § 875)—the relevant portion of which carries only a two year sentence. This law shows up in 29 of the federal cases we examined (37 percent).

In cases in which the attacks are highly targeted against an individual, prosecutors have sometimes relied on the federal stalking law (18 USC § 2261A), charges under which appear in nine cases (12 percent). And in 12 cases (15 percent) involving hacking or appropriation of social media accounts, prosecutors have used the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (18 USC § 1030), the identity theft law (18 USC § 1028A), or both.

As we noted above, these cases produce sentences on average dramatically lower than those charged under the child exploitation laws. This is partly because the child pornography laws carry particularly severe sentences, but it’s also because sextortion cases end up outside of the arena of sex crimes and prosecuted as hacking and extortion cases. As we argue in “Closing the Sextortion Sentencing Gap,” Congress should examine closely the question of whether sextortionists who prey on adults—sometimes many of them—are receiving excessively lenient treatment under current law. Suffice it for present purposes to observe that there is no analog for adult victims to 18 USC § 2422’s criminalization of coercing a minor to engage in sexual activity (at least if that sexual activity does not involve prostitution or otherwise illegal activity). And while 18 USC § 875, the extortion statute, permits a 20-year sentence for the transmittal of a ransom demand, and the same stiff term for anyone who transmits a “threat to injure the person of another,” the statute offers only a two-year sentence for anyone who, “with intent to extort from any person . . . any money or other thing of value, transmits in interstate or foreign commerce any communication containing any threat to injure the property or reputation of the addressee.” It contains no enhanced sentence for the situation in which the thing of value in question being extorted is coerced production of nonconsensual pornography.

Another area in which current law looks deficient is at the state level. State prosecutors are among those who have done the most dedicated work in this area. But the data in aggregate strongly suggest that they are working with weak tools compared to their federal counterparts. The average sentence in the six state cases that have reached the sentencing phases is 88 months (seven years and four months). By contrast, the average sentence in the 49 federal cases that have produced a sentence less than life in prison (one case has produced a life sentence) is, by contrast, 349 months (a little over 29 years).

This dramatic disparity is only partly a reflection of strong federal child pornography sentencing. It also reflects weak state laws that are under-punishing serious offenders. For example, Joseph Simone in Rhode Island, who sextorted 22 teenage boys in a particularly brutal fashion, received only one year in prison and two more years of home confinement (and an additional period of probation).106 Similarly, it’s hard to imagine that had Cameron Wiley been prosecuted in federal court for sextorting two underage girls, he would have received only seven months in jail and an additional 18 months of probation—as he did in Wisconsin state court.107

Case studies in sextortion

Sextortion cases vary. Most involve relatively simple social media manipulations, in which the perpetrator tricks victims into sending him one or more nude photographs and then uses the threat of release of those photos to extort the production of larger numbers of more explicit ones. These attacks tend to have large numbers of victims and to be relatively indiscriminate. As noted above, however, some sextortion cases involve highly targeted attacks on individuals known personally to the perpetrator. A smaller number involve one or more forms of hacking, either intrusions into victims’ social media accounts or, in some instances, the actual hacking of their computers and the remote controlling of their webcams.

Congress should examine closely the question of whether sextortionists who prey on adults—sometimes many of them—are receiving excessively lenient treatment under current law.

What follows are detailed accounts of eight sextortion cases; the accounts are culled from court documents to give readers a flavor of both the common threads between the cases and the diversity among them. Our goal is both to describe the mechanics of sextortion and to portray how the crime operates on its victims, with the aim of communicating the seriousness of these offenses.

Jared James Abrahams

Jared James Abrahams, a California college freshman studying computer science, was arrested in 2013 for the sextortion of the woman who would become the crime’s best-known victim: Cassidy Wolf, that year’s winner of the Miss Teen USA beauty pageant.108 Abrahams and Wolf had gone to high school together in Temecula, California.109 She first suspected that something was wrong when she received notifications from several social media services that someone had tried to change her passwords. Thirty minutes later, Abrahams emailed her, demanding that she either send him nude pictures of herself on the social media service Snapchat, send a “good quality video,” or Skype with him “and do what I tell you to do for five minutes.” Otherwise, he would upload naked pictures of her to her social media accounts. Wolf did not recognize the photos, which appeared to have been taken from her webcam.110

Investigators later found that Abrahams had sextorted at least 12 young women, including women from Ireland, Canada, and Moldova and controlled the computers of between 100 and 150 women111 He installed keylogger software on his victims’ computers to record their passwords and gain access to their social media accounts—though he mocked Wolf for making her passwords so easy for him to guess.112 He would also install the malware programs Blackshades and DarkComet, which enabled him to remotely control his victims’ webcams without their knowledge and surreptitiously take photographs.113 He often contacted victims using other email addresses that he had hacked, and would use the productivity software Bananatag and Toutapp to monitor when his victims read his emails.114

One victim wrote to Abrahams, “Please remember im only 17. Have a heart.” He responded, “I’ll tell you this right now! I do NOT have a heart!! However I do stick to my deals! Also age doesn’t mean a thing to me!!!”115

In order to hide his IP address, Abrahams used a Virtual Private Network (VPN) service that advertised it did not keep logs,116 along with a dynamic DNS service offered by No-IP.com.117 Investigators ultimately traced the IP address back to Abrahams, discovering that a person with the same username used to register for No-IP.com had also posted on hacking forums bragging that he had infected the computer of someone who “happened to be a model.” The username in question? “Cutefuzzypuppy.”118

Abrahams was charged with one count of computer fraud and three counts of extortion, and pleaded guilty to all charges.119 He was sentenced to 18 months in prison.120

Lucas Michael Chansler

From 2007 to 2010, Lucas Michael Chansler targeted nearly 350 young girls in his sextortion ploy—so many that, after his arrest, the FBI launched a prolonged online campaign to locate the scores of girls whom he had victimized.121 Agents wanted to interview the girls for information on Chansler’s case, but they also wanted to provide closure. After all, there was no other way that victims would know that their torture had been ended for good.122

Hiding his IP address through proxy servers, Chansler relied on catfishing to reach out to potential targets through social media.123 Pretending to be a teenage boy—usually interested in skateboarding—who was looking for a friendship or flirtation with the victim, Chansler would ask to video chat with the victim and display video of a naked boy in order to hide his identity. He asked the victims to strip on camera, and he secretly recorded the stream.124 In one case, he tricked four young girls at a sleepover into posing for him on Stickam, a now-discontinued livestreaming service notorious for the predatory behavior of some of its users and notorious as well because of its owner, a businessman who also controlled a network of pornographic websites.125 Once Chansler had the video or pictures that he wanted, he threatened to release the material to the victim’s friends and family or upload it to a public website unless the victim provided him with more.126 In an interview with the FBI, one victim described the depression and panic caused by Chansler’s demands that she constantly be available to respond to his messages: “I felt like a slave. . . . I remember just lying in bed in silence and just thinking. I felt like God was so disappointed in me, and I didn’t know what to do.”127

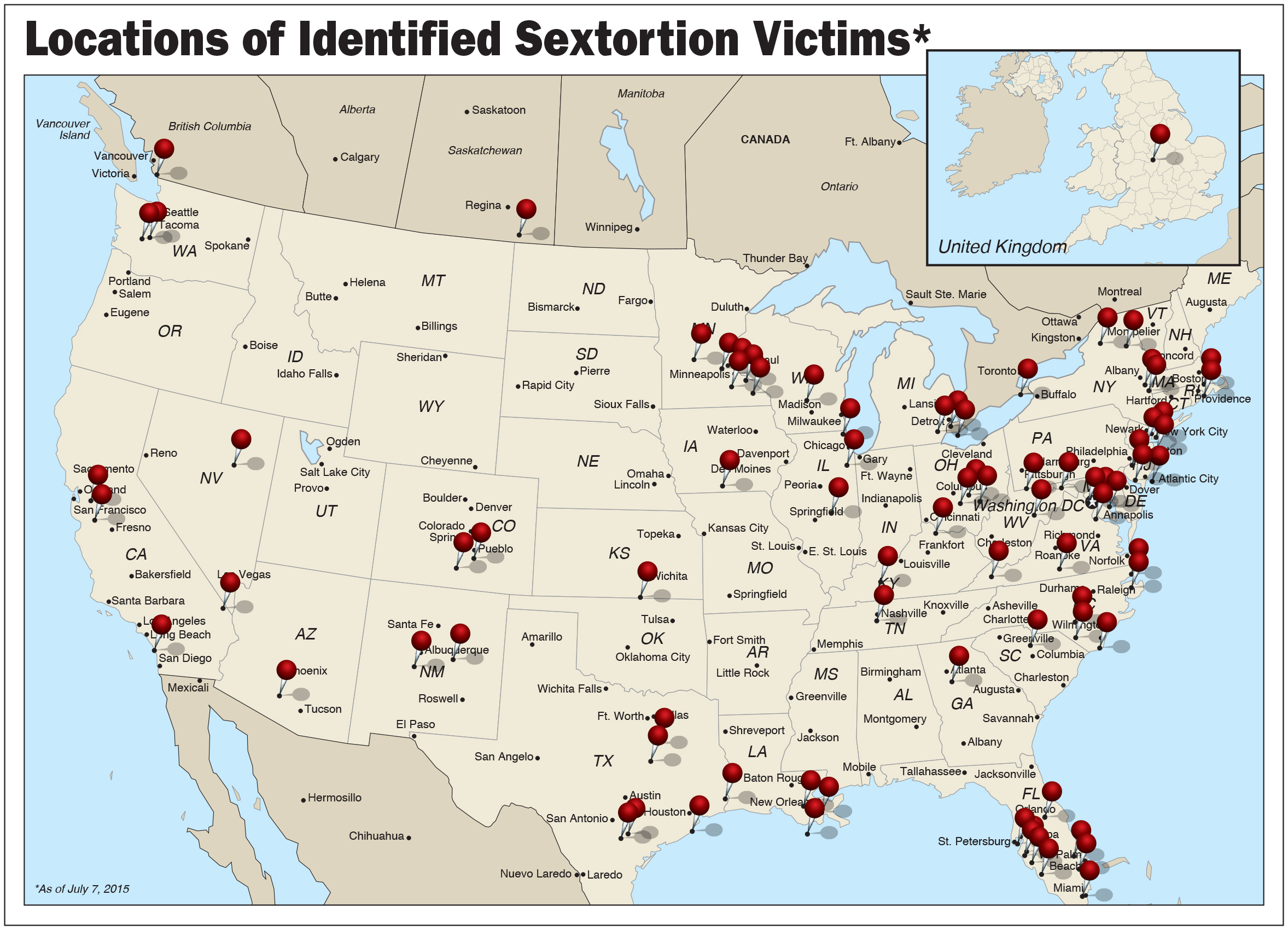

[FBI MAP: https://www.fbi.gov/news/stories/2015/july/sextortion; https://www.fbi.gov/news/stories/2015/july/sextortion/image/map-showing-locations-of-identified-sextortion-victims]

Speaking with an FBI agent after his arrest, Chansler explained that he targeted young girls because they were more likely to believe his scam.128 He was charged with four counts of extortion, 14 counts of producing child pornography, one count of receiving child pornography, and one count of possessing child pornography.129 He pleaded guilty to all 14 counts of producing child pornography and has been sentenced to 105 years in federal prison.130

Ivory Dickerson and Patrick Connolly

Ivory Dickerson and Patrick Connolly never met in person, but they functioned together as a kind of sextortion team: together, the FBI claims, they targeted more than 3,800 underage girls.131 Dickerson—a civil engineer in North Carolina—and Connolly—a British military contractor working at a U.S. base in Baghdad—worked in tandem,132 with Connolly usually reaching out to potential victims over the internet in order to trick them into installing the malware Bifrost.133 Then the two would collaborate in blackmailing their victims with photos taken surreptitiously using their webcams or with personal information obtained by their computers.134 It took four years of investigation to track them down.135

In one case, Connolly threatened to post a girl’s email address online and to harm her younger sister unless she provided photographs.136 In another, he told a victim that he would make her “the most well-known girl at school” unless she provided him with pictures. “Are you sure you want to drive to school tomorrow?” he asked, claiming that he saw her at school every day.137

The FBI initially contacted Dickerson believing that he might be one of Connolly’s victims; they suspected that Connolly may have gained control over Dickerson’s computer and used it to attack other computers as a way of hiding his tracks.138 Soon, however, they realized that Dickerson himself was also behind the attacks, discovering evidence of hacking and videos of graphic, self-produced child pornography on his computer.139 Dickerson also used a program that would allow him to search the Internet for vulnerable webcams that he might be able to hack.140

Dickerson explained to the FBI that he while he had never met Connolly in person, he had a good idea of his identity: as Dickerson’s co-conspirator, Connolly referred to himself as “Lauren,” and would often send Dickerson pictures of Connolly and information about Connolly’s life.141

Dickerson was sentenced to 110 years in prison after pleading guilty to all charges: three counts of producing child pornography, one count of possessing child pornography, and two counts of computer fraud.142 Connolly was charged with five counts of producing child pornography, six counts of extortion, and one count of computer fraud.143 He pleaded guilty to one count of producing child pornography,144 and was sentenced to 30 years in prison—though the sentencing judge declared, “If I could sentence you to life, I would.”145

Michael C. Ford

Investigators initially discovered Michael C. Ford when looking into an anonymous sextortionist whom they believed might be using a State Department IP address to obscure his identity.146 As it happened, the IP address was not a ruse: the investigation ultimately traced the sextortion back to Ford, an employee at the U.S. Embassy in London.147 Ford contacted his victims from his cubicle, storing elaborate spreadsheets of his victims’ emails and passwords on his work computer.148 His sextortion began the year he was hired at the Embassy; he was busy sextorting at work for six years without anyone at the Embassy noticing before he was finally arrested.149

Ford relied on a phishing scheme to gain his victims’ passwords and steal explicit photos from their accounts, along with personal information such as the victims’ addresses and phone numbers. He sent thousands of emails posing as a member of Google’s “Account Deletion Team,” notifying victims that their Google accounts were set to be deleted and requesting their passwords in order to prevent the purging of their account.150 (Ford saved drafts of these phishing emails on his Embassy computer.)151 He primarily targeted young women who belonged to college sororities or aspired to be models,152 though in one case he sextorted a young man for a female friend’s passwords.153 The man refused to send along more pictures because, in his words, “I’m 16 in those photos [that Ford had already obtained] and if you post/distribute child porn, you’re going to have a bad time.” Ford responded, “Do you really think I care?”154

Once he obtained a victim’s passwords and accessed her account, he would threaten to release her photos to family members or publish the photos on the Internet unless the victim provided him with video of women’s changing rooms.155 Sometimes, he would threaten to make public the victim’s contact information and address as well.156 In several cases he made good on his threats, at one point emailing a victim’s mother a picture of her with a note reading, “Check out your little girl.”157 Some of his victims began to fear for their physical safety: one woman slept with a knife under her pillow, while another considered obtaining a gun to protect herself.158

Ford had successfully hacked into 450 computers and threatened 75 victims at the time of his arrest.159 He was indicted on nine counts of cyberstalking, seven counts of computer fraud, and one count of wire fraud,160 and pleaded guilty to all charges.161 He was sentenced to 57 months in prison.162

Christopher Patrick Gunn and Jeremy Brendan Sears

Christopher Patrick Gunn had two methods of catfishing young girls to extort them for sexual photos.163 In one, he would reach out through a fraudulent Facebook profile and pretend to be a new kid in town looking for friends—a ruse that conveniently explained away why his potential victim never would have heard of him before.164 In his second method, he would contact girls over online chatting apps such as Omegle—a service that randomly pairs chatters for anonymous conversations163—and pretend to be none other than pop heartthrob Justin Bieber, roaming the Internet in the hopes of meeting his fans. As Bieber, he would offer free concert tickets or backstage passes to his young fans if they sent photos or video of their bare chests. He would then quickly move to make ever-more-invasive demands of his victims; if they initially sent a picture of their breasts, he would push for a full-body photo or a photo of the girls’ friends bare-chested as well.164

Gunn was not alone in targeting young Beliebers as potential victims for sextortion. Jeremy Brendan Sears got his start in the “Bieber Hijacking and Trolling Company,” an online group that trolled girls’ fan-sites for Bieber and the boyband One Direction.165 Soon, Sears struck out on his own, harassing the young website owners and spamming their pages in order to extort the girls for explicit photos and videos.166 The fans, who had invested months or even years of work in collecting pictures of their idols, were desperate to regain control over their webpages—which was exactly what made them vulnerable to Sears.167 Sears would also catfish victims using fake social media profiles and post victims’ contact information online, promising to remove it only if the victims provided photographs or video.168 When interviewed by the FBI, Sears stated that his sextortion had “a very minor sexual thing to it,” but that the primary appeal was the “power” it offered him over his victims.169

Christopher Patrick Gunn was charged with six counts of producing child pornography, two counts of possessing child pornography, seven counts of stalking, 20 counts of extortion, and eight counts of interstate transmission in aid of extortion.170 He pleaded guilty to two counts of producing child pornography and four counts of extortion,171 and was sentenced to 35 years in prison.172

Jeremy Brendan Sears received a sentence of 15 years173 after pleading guilty to just one count of producing child pornography.174 He was originally charged with 16 counts of producing child pornography, 11 counts of distributing or receiving child pornography, one count of possessing child pornography, one count of extortion, one count of computer fraud, and one count of aggravated identity theft.175

Richard Finkbiner

When FBI agents searched Richard Finkbiner’s rural Indiana home in 2012, they discovered more than 22,000 video files saved on his computer, roughly half of which were sexually explicit and most of which depicted minors.176 Finkbiner routinely sextorted so many people for these videos, he told the FBI, that it was impossible for him to recognize the images of any one particular victim that agents had presented to him: he had too many victims to recall them individually.177

Finkbiner would reach out to potential victims—usually teenage boys—through Omegle or other anonymous chatting programs. Like Chansler, he would ask them to strip and perform sexual acts while he surreptitiously recorded them, hiding his own identity by displaying sexually explicit videos in place of his own camera feed.178 Then he would threaten to upload the video to pornographic websites unless the victims emailed him—and as soon as they did so, he would threaten to distribute the material to friends, family, and school acquaintances unless they agreed to become what he referred to as his “cam slaves.”179 In as many as three cases, Finkbiner may have used image editing software to trick his victims into believing that he had uploaded their videos to pornographic sites.180

At one point, a 17-year-old girl wrote to Finkbiner saying that she had attempted suicide the previous night and would attempt it again if he did not stop his requests. Finkbiner wrote back, “Glad i could help.”181

When one boy protested against Finkbiner’s requests, Finkbiner responded, “yes it is illegal im ok with that … i wont get caught im a hacker i covered my tracks.”182 In fact, he made no effort to hide his IP address, and the FBI was able to trace the email and Skype accounts he used for sextortion to the small Internet service company registered in his name.183

Overall, Finkbiner sextorted ” “hundreds, if not thousands, of . . . minors and adults all over the world,” prosecutors claimed.184 Most of the victims were minors. He was charged with six counts of producing child pornography, 20 counts of interstate extortion, eight counts of interstate transmission in aid of extortion, two counts of possessing child pornography, and seven counts of stalking.185 He pleaded guilty to all seven counts of stalking, two counts of producing child pornography, and 15 counts of extortion,186 and was sentenced to 40 years in prison.187

Adam Savader

Adam Savader, a college student active in Republican politics, spent the summer and fall of 2012 in a prestigious position as Paul Ryan’s “sole intern” on the Romney-Ryan presidential campaign.188 But by September 2012, he had begun sextorting,189 targeting young women whom he knew from high school or college190—one of whom had threatened to take out a restraining order against him in the past.191 In the case of one victim who was similarly politically active, Savader threatened to release her photos to her mother, her sorority sisters, and the Republican National Committee.192 He would usually goad his victims into responding to him: a typical series of messages reads, “I’m about to send those pics… Should I? If not tell me. I’m running out of patience… Answer me now or pay.”193

Savader extorted at least 15 women in total,194 hacking into victims’ email and social media accounts in order to access sexually explicit photos stored there. His college and hometown connections with his victims allowed him access to their accounts, as he could reset their passwords by guessing the answers to security questions that asked about information such as high school mascots and street of residence.195

Once he had the photos, he would contact victims through Google Voice, a service that allows users to create a new number from which to receive and forward calls.196 Savader’s multiple Google Voice accounts allowed him to keep his cell phone number hidden from his victims, and may also have allowed him to prevent them from contacting him back in turn: Google Voice allows users to turn off call forwarding to their devices,197 and one victim’s account of her failed attempts to contact Savader is consistent with Savader’s having used this function.198 Savader used freshly created email accounts to register for the Google Voice numbers,199 but both the forwarding number for the Google Voice accounts and the IP addresses used to create those email addresses traced directly back to Savader.200

Savader was sentenced to two-and-a-half years on one count of cyberstalking201 after pleading guilty to one count of cyberstalking and one count of extortion;202 he had originally been charged with four counts of each.203 While in prison, Savader has registered a Super PAC lobbying for legislation supporting improved reintegration of previously incarcerated individuals into society. According to Savader’s father, the PAC will refrain from fundraising until his son is released from prison.204

Rinat: Israeli case of sextortion

The problem of sextortion is not by any means limited to the United States. In 2013, a 30-year-old man was convicted in Israel of extortion, sexual harassment, and the publication of obscene material after posing as a female soldier on various social media sites and tricking young girls into communicating with him. Under pressure, the communications became sexually explicit and exploitative, with the offender requesting nude photos and other pornographic material from at least three minors.

In one instance, the perpetrator filmed a 13-year-old female minor without her knowledge over Skype after pressuring the girl to masturbate on camera. The young girl eventually attempted to end the relationship with the person she knew as “Rinat,” cutting off communication with the offender. However, the man then told her that he had recorded all of their online conversations and would publish the material if she refused to continue their relationship. After the victim refused, the sextortionist published explicit images of the minor on Facebook.

In another instance, the perpetrator pressed a different 13-year-old minor to engage in sexual acts over Skype. When the minor told the sextortionist that her mother was in the room, he asked and eventually convinced his victim to pretend to change her clothes in front of her webcam, so as not to attract the attention of her mother, and to allow him to see her naked. According to the court opinion, the victim’s mother was present in the room as she was sextorted.

The court wrote: “The thought that children are unsafe in their own home is a difficult one, and it turns out that there, in their own room in their house under the watchful eye of their parents, the appellant managed to trick them, hurt them, and cause them unimaginable harm.”

In denying the man’s appeal against the two-year prison sentence imposed on him, the Israeli Supreme Court stated, that “the appellant’s action, absent any physical contact, does not reduce the severity of the offence.” In a chilling conclusion, the court wrote: “The thought that children are unsafe in their own home is a difficult one, and it turns out that there, in their own room in their house under the watchful eye of their parents, the appellant managed to trick them, hurt them, and cause them unimaginable harm.”205

Impact of sextortion on victims

The harm that many victims experience as a result of sextortion is, indeed, unimaginable. But it is also real. Victims of sextortion feel a justified sense of powerlessness and vulnerability: they are at the mercy of their hackers. Victims have described descried feeling like a “slave” to the hackers during the sextortion scheme.206 Victims of these schemes spend every moment in fear of the next message demanding more compromising pictures or videos, living in perpetual anxiety of the risk of public exposure. With every new picture sent to the hacker is the worry that it isn’t enough or that the hacker will never leave. Related is the feeling of helplessness: the inability to reach out to others about what is going on for fear of the attacker’s retaliation. The days, weeks, and months under the sextortionist’s control can be an absolute “nightmare,” where a victim is “trapped” and can’t “talk to anyone.”207 One teenager told investigators that the experience “felt like I was being virtually raped.”208

The traumatic effects on child victims can be particularly severe. Younger victims are sometimes paralyzed by the potential social repercussions of sextortion. One victim recounted that, as a young teenager, she was “already getting teased in middle school” and was terrified she might lose friends and become a target of cruel teenage bullying if her classmates found out what was going on.209 The nature of sextortion also makes for easy victim-blaming: the victims, after all, took pictures and videos of themselves and sent them along. Why didn’t they just refuse to go along with the scheme?

Martha Finnegan, an FBI expert in child forensics explains that this kind of psychological cruelty—forcing the victim to participate in the production of these images—can have “a devastating emotional effect” on the victims:

[T]hat’s what society doesn’t get: Yes, the girls participated in this. But they’re children; they’re still very much victims. Even though they haven’t been touched, the trauma level we see is as severe as hands-on offenses, because a lot of these kids don’t know how to end what can go on, sometimes, for years. … And they think it’s not happening to anyone else.210

Children are often the easiest targets of these sorts of crimes not only because of their social vulnerability, but because they often do not realize that what is happening is criminal behavior. They are often left defenseless and too scared to admit to their parents or to anyone else what is happening. They also sometimes have no idea when threats are completely idle ones. One young sextortion victim complied with demands for nude photos because her attacker threatened to “blow up” her computer if she did not, and the computer was a treasured new Christmas present.211

That defenselessness does not cease even in when the hacking is over and the sextortionist is prosecuted. One of Luis Mijangos’ victims described the visceral fear of her hacker that has stayed with her since, despite Mijangos’ prosecution and ultimate jail time: “He [still] haunts me every time I use the computer.”212 Another one of Mijangos’ victims explained that moving away from the Los Angeles area has not made her feel any safer: as long as he had an Internet connection, Mijangos was able to attack from anywhere, at any time. This is a crime from which some victims have a great deal of trouble escaping. They carry the weight of this anxiety and distrust with them.

To make these points tangible, consider some of the victim impacts from the case studies in the previous section. In sentencing Abrahams, for example, the judge declared: