Following the calls of public health researchers, advocates, elected officials, and his specially appointed commission, President Donald Trump recently announced his intention to designate the opioid crisis as a national emergency.

In 2015, 52,404 people in the United States died from drug overdoses. Adjusting for age, that equated to 16.3 deaths per 100,000 people, more than 2.5 times higher than the rate in 2000 (6.2 per 100,000). As the president’s commission wrote in its interim report, “The average American would likely be shocked to know that drug overdoses now kill more people than gun homicides and car crashes combined.”

Opioids are the main driver of this trend, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Opioid overdoses—from both prescription (e.g., oxycodone and methadone) and illicit (e.g., heroin and, increasingly, fentanyl) sources—have quadrupled since 1999 and caused over 60 percent of all overdose deaths in 2015. Early estimates for 2016 suggest the numbers have gotten worse.

As staggering as the climb in the nation’s overdose death rate has been, the deepening crisis has hit some populations even harder. Older, working-age adults and non-Hispanic whites experienced faster-than-average increases in drug overdose death rates during the 2000s, growing by factors of 5 and 3.5, respectively. New research by Alan B. Krueger for the Brookings Papers on Economic Activity finds that increases in opioid prescriptions might account for 20 percent of the decline in men’s labor force participation since 1999.

Although virtually no community remains untouched by this epidemic, some parts of the country have borne the brunt of the recent increases.

The media have increasingly chronicled the struggles of people and places affected by growing drug addiction and overdose deaths. Whether in sparsely populated rural areas, the urban core, or suburbia, communities across the country are grappling with similar challenges around access to treatment, effective interventions, and sufficient capacity and resources—challenges that run deeper in many of the economically distressed communities most affected by the opioid crisis.

As policy researchers who are focused on issues of place, poverty, and human services provision, we have been paying close attention to newly emerging data about drug-related deaths and the evolving debate about proper policy responses. We are not addiction experts or clinically licensed practitioners, but we believe the intervention solutions developed nationally must reflect what we know about poverty and the safety net at the local level. In particular, the availability and accessibility of governmental, nonprofit, and for-profit entities providing treatment services vary widely from community to community. Moreover, there is mounting evidence that prevention and treatment of drug addiction require intensive and highly professionalized services. Research shows that effective substance abuse programs also must treat mental health, physical health, and age-related conditions that often accompany addiction. Yet the extent to which such services are available in communities across the country is not clear.

To better understand the geography of the growing drug overdose epidemic, its intersections with poverty and economic distress, and the extent to which communities are equipped with the resources and capacity to address the crisis, the following analysis draws on a range of data sources. We assembled county-level data from the CDC on drug poisoning (which we also refer to as “overdose”) death rates in 2000 and 2015, and poverty estimates from the 2000 decennial census and the 2011-15 American Community Survey. While few good sources of data exist on community-level capacity and provision of addiction services, we drew upon county-level data on nonprofit human service delivery organizations from the National Center for Charitable Statistics (NCCS) in 2013, the most recent year available, to provide insight into the realities of substance abuse programming on the ground. We identified nonprofit human service organizations that are registered as primarily providing substance abuse dependency, prevention, and treatment services. (For more detail on the data used, see the Note on Methods.)

Our analysis of these compiled data sources finds:

More than three-quarters of the nation’s counties reported at least 10 overdose deaths per 100,000 people in 2015.

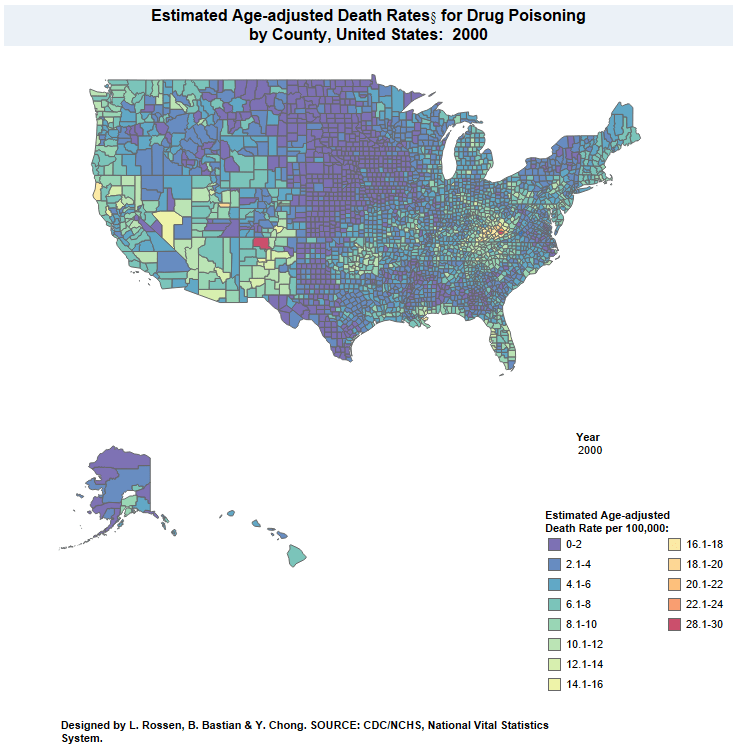

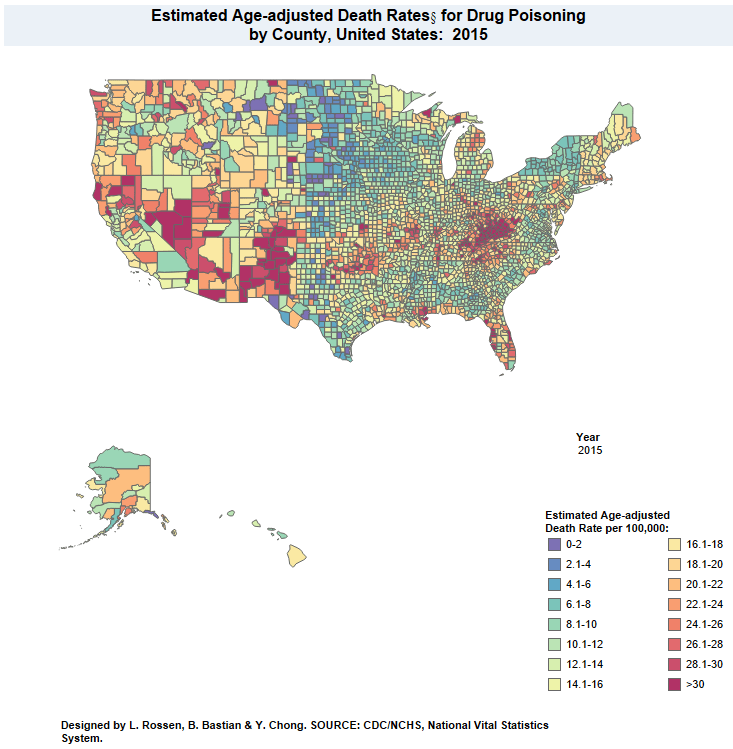

County-level data on drug poisoning death rates reveal the uneven clustering of overdose deaths across the country. The CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) publishes annual drug poisoning death rates at the county level through its data visualization gallery. The data set assigns counties to one of 16 categories—from 0 to 2 deaths per 100,000 in the first category, to 2.1 to 4 deaths per 100,000 in the second category, and so on until reaching the highest category of more than 30 deaths per 100,000.

In 2015, more than three-quarters of the nation’s counties registered double-digit death rates from overdose (Figure 1). Almost one-third, or 982 counties, experienced death rates of 18.1 per 100,000 or higher—that is, at least one category above the national average.

Click to enlarge

Of the counties experiencing above-average overdose death rates in 2015, 646, or roughly two-thirds, were in rural America, 154 (16 percent) were in small metro areas, 126 (13 percent) were suburban counties in the nation’s 100 largest metro areas, and 56 (6 percent) were urban counties in those metro areas. That distribution roughly mirrors the overall allocation of counties across these four geographic categories: 65 percent of all counties are rural, 17 percent are in small metro areas, 15 percent are suburban, and 4 percent are urban, according to our typology. (For more detail on geographic definitions, see the Note on Methods.)

However, looking at patterns within each type of geography reveals that urban counties were the most likely to report above-average death rates. Among urban counties, 49 percent posted death rates of 18.1 per 100,000 or higher, including Baltimore County, Md.; Denver County, Colo.; Philadelphia County, Pa.; and Pima County, Ariz. (home to Tucson). Roughly one-third, or 32 percent, of rural counties, 29 percent of small metro counties, and 28 percent of suburban counties struggled with drug poisoning death rates of that magnitude.

It is difficult to translate these geographical patterns into population counts given the categorical nature of the NCHS data. However, a rough calculation based on county population and the lower bound of each county’s death rate category suggests that, in 2015, 41 percent of all drug overdose deaths occurred in urban counties, 26 percent took place in the suburbs, 18 percent in small metro areas, and 15 percent in rural communities (Figure 2).

Click to enlarge

Almost every county in the United States experienced an uptick in drug overdose deaths between 2000 and 2015. None registered a decline.

The NCHS’ mapping tool paints a stark picture of the extent to which drug overdose deaths—fueled by the growing opioid crisis—climbed between 2000 and 2015. (Please see the Methodology overview for a discussion of using the NCHS data to measure change over time.)

Only 35 counties (1 percent of all counties) experienced no change in their overdose death rates between 2000 and 2015. Each of those counties fell in the lowest category (0 to 2 deaths per 100,000) in both years. But those communities were clearly exceptions to the national trend.

To place the national trend in the context of these 16 categories, the increase of 10 deaths per 100,000 between 2000 and 2015 (from 6.2 to 16.3 deaths per 100,000) is the equivalent of moving up five categories. Most counties across the nation (60 percent) experienced a rise of at least that magnitude, and 43 percent registered a move of six categories or more—what we call “high to severe” increases—which roughly means they experienced increases of anywhere from 12 to 28 deaths per 100,000 people (Figure 3). As the NCHS maps suggest, of those hardest-hit counties, more than half were in the South and another 1 in 5 were in the West.

Click to enlarge

Less-populous and lower-density communities have experienced some of the sharpest upticks in their drug poisoning death rates since 2000. Among the counties registering high to severe increases in overdose deaths between 2000 and 2015, 72 percent were rural, 14 percent were in small metro areas, and 11 percent were suburban. Only 4 percent were urban.

Yet, once again, trends within each geographic category underscore the depth of the challenge across different kinds of communities. Nearly half of all urban and rural counties, or 47 percent, experienced high to severe increases in the drug poisoning death rate between 2000 and 2015, and about one-third of small metro area and suburban counties (34 and 32 percent, respectively) registered increases in that range.

Poor counties—and counties that became poorer between 2000 and 2015—have been among the hardest hit by the overdose epidemic.

While this broadly shared crisis isn’t confined to economically struggling places, there’s a reason the national conversation has highlighted economic distress and instability as a factor driving “deaths of despair,” which include drug overdose deaths.

Among high-poverty counties—those with poverty rates of 20 percent or higher—41 percent (342 of 829) reported above-average death rates due to drug poisoning in 2015. In contrast, only 13 percent of counties with poverty rates below 10 percent had above-average death rates (56 of 438).

Moreover, and perhaps not surprisingly, counties that became significantly poorer—or remained very poor—over this period registered larger increases in the rate of drug overdose deaths on average than counties that became less poor (Table 1). For example, counties that moved from low to moderate or high rates of poverty experienced an increase in their drug poisoning mortality rate of almost five categories on average—the equivalent of an increase of about 10 deaths per 100,000 people, similar to the national trend. Counties moving from moderate to high poverty rates experienced even steeper increases in overdose deaths on the whole, moving more than six categories on average. In contrast, counties where poverty rates fell to below 10 percent from 2000 to 2015 experienced much smaller increases in drug poisoning deaths.

That the most distressed and high-poverty counties are often experiencing the largest increases in drug-related deaths underscores the strong connection between economic hardship and social inequality across urban, suburban, and rural America. Such relationships among geography, poverty, and addiction also are concerning because mounting evidence indicates that many high-poverty counties—particularly those in rural and suburban areas—lack access to professional addiction treatment services and resources.

The vast majority of counties have no registered substance abuse nonprofits, with the largest gaps found outside the urban core and in higher-poverty areas.

One very simple indicator of local nonprofit capacity is the presence of any registered nonprofit organizations primarily focused on substance abuse service provision. Roughly 73 percent of all counties in our data have no registered substance abuse nonprofits.

Even more striking, more than 80 percent of rural counties and almost 60 percent of suburban and small metro counties that reported above-average rates of drug poisoning deaths in 2015 do not contain a registered nonprofit substance abuse service provider. In contrast, all of the urban counties with above-average overdose death rates in 2015 have at least one such provider.

Not only are registered substance abuse nonprofits scarce (outside the urban core) in counties that reported the highest drug poisoning death rates in 2015, but counties with the steepest increases in overdose deaths in recent years are even less likely to be home to a registered substance abuse nonprofit.

Nearly 80 percent of counties experiencing high or severe increases in drug poisoning deaths have no registered substance abuse nonprofit organizations (Figure 4). By comparison, 67 percent of counties with only a slight or no increase in drug-related deaths do not contain a registered substance abuse service nonprofit.

Click to enlarge

Areas hit hardest by increases in drug overdose deaths, but without registered substance abuse nonprofits, are disproportionately likely to be located in rural areas. Almost 90 percent of rural counties experiencing high to severe increases in drug poisoning deaths have no registered substance abuse nonprofits; more than 60 percent of suburban and small metro counties experiencing the most significant increases do not contain a registered substance abuse nonprofit.

As might be expected, the poorest counties also are most likely to lack nonprofit substance abuse service organizations. Roughly 8 in 10 counties experiencing the largest increases in drug overdose deaths and with poverty rates over 20 percent do not contain a single registered substance abuse nonprofit (Table 2).

It should be noted that these data likely overstate the absence of nonprofit substance abuse programs (click here for more detail on methodology.) Many counties without a registered nonprofit may be home to programs operated by county government, health care systems, satellite offices of regional nonprofits, or small faith-based organizations, none of which would appear in these NCCS data.

However, the lack of registered nonprofit service organizations in such a large share of counties is striking. Absent local registered nonprofits providing substance abuse services, we can imagine counties struggling to maintain the social service infrastructure necessary to address rising need. These numbers also suggest the challenges that many people fighting addiction face in finding and accessing treatment. For instance, an NPR profile from January 2017 described the two-hour drive one resident of rural Logan County, Colorado—which registered between 16.1 and 18 overdose deaths per 100,000 in 2015—undertakes to find treatment. Similarly, a New York Times story in March 2017 noted that, particularly in rural areas, “Counseling centers and doctors who can prescribe addiction-treating medications are often an hour’s drive away, in communities with little public transportation.” Such distances can become insurmountable for people living in poverty or for those who may have lost their driver’s licenses because of their addiction.

Implications

Widespread increases in opioid addiction have led to greater public discussion about the consequences for individuals, families, and communities across the country. Chief among these are concerns about overdose deaths and the services needed to address a shocking health crisis in nearly every urban, suburban, and rural area. We find, much like anecdotes from recent media narratives, many areas hit hardest by the rise of drug overdose deaths appear to have the least capacity to provide treatment or services.

The absence of nonprofit service providers matters for many reasons. It means that those struggling with drug addiction may have few options for treatment nearby. In communities outside the urban core, many may have to travel great distances to access services. Counties with few or weakly resourced nonprofit organizations depend more on publicly provided services and behavioral health services offered through health care systems. Moreover, evidence suggests that substance abuse service providers working in rural and suburban areas, particularly those working with low-income populations, rely heavily upon Medicaid funds to cover operating costs and care.

Given the limited availability of services and the crisis of addiction, we should expect the federal government—particularly a White House that campaigned on solving the problem and a Republican Party that represents many of the hardest-hit areas—to seek additional funds and ways to boost capacity. Instead, the current budget and health care proposals do just the opposite. Proposed cuts to Medicaid would undermine a key source of funding for addiction services and interventions, particularly for lower-income households. Broader reductions in funding for social service and safety net programs also would reduce the resources available for treatment and prevention programs. Neither state and local governments nor charitable philanthropies have the funds to fill in these proposed federal cuts.

While President Trump’s Commission on Combating Drug Addiction and the Opioid Crisis warns that the “scourge” of drug use and addiction will affect every family in America unless bold action is taken, the federal budget proposals under debate in Washington, D.C. fall far short of such action. Without efforts to expand local service capacity and to devote greater funding to interventions that work, the administration and Congress will leave our communities and families more exposed—not less—to addiction and its consequences for years to come.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).