Part 5 of “Baked in and Wired: eDiplomacy @ State“

| « Read Part 4: Internet Freedom | Read Part 6: Conclusion and Recommendations » |

What’s the Issue?

The third area at State attracting serious ediplomacy resources is knowledge management. This was the first use ediplomacy at State. It is also emerging as one of the most far-reaching applications of ediplomacy, and has garnered the attention of big business as well as other foreign ministries. It is attempting to solve some of the toughest organizational challenges foreign ministries face including:

- helping managers realize when expensive knowledge resources are being wasted or duplicated to deliver cost savings;

- delivering immediate and easy access to the organization’s total knowledge stock on an issue or subject in order to improve decision and policymaking;

- promoting knowledge transfer and reducing knowledge loss, e.g., during personnel transitions; Identifying centers of expertise and valued knowledge sources;

- allowing managers to know what knowledge resources the organization has and where to find them.

Knowledge management is an issue with which the private sector is also wrestling. MIT’s Andrew McAfee undertook a detailed assessment of what he calls Enterprise 2.0—“the use of emergent social software platforms by organizations in pursuit of their goals” (p. 73) tools that mirror those managed by the Office of eDiplomacy. Towards the end of Enterprise 2.0, he writes (pp. 186-7):

Discussions about ROI [return on investment] from Enterprise 2.0 always remind me of an experience I had during a seminar in 2006.

In this seminar, I was presenting the concepts and structure of my MBA course to a diverse group of Harvard Business School colleagues. Pretty early on, one of the professors in the finance area asked me the question I was most dreading and least prepared for: ‘Andy, what do you teach students about conducting a financial analysis of a proposed IT investment? How do you build a business case for IT?’ I was about to launch into a long-winded and poorly argued answer, but Bob Kaplan spoke up first. ‘You can’t,’ he said.

Like all good academics, Kaplan provided McAfee with one of his books, which McAfee goes on to cite (p. 187):

None of these intangible assets has value that can be measured separately or independently. The value of these intangible assets derives from their ability to help the organization implement its strategy…. Intangible assets such as knowledge and technology seldom have a direct impact on financial outcomes such as increased revenues, lowered costs, and higher profits. Improvements in intangible assets affect financial outcomes through chains of cause-and-effect relationships.

That is unfortunate for foreign ministries, whose principal asset is the knowledge stored in their workers’ brains and the millions of documents they have written and stored in a myriad of locations (cables, emails, Word documents, blogs, intranets etc).

In addition, while it is perhaps true that “knowledge and technology seldom have a direct impact on financial outcomes,” there are obvious examples at foreign ministries where a failure to price knowledge has a direct financial bearing on the organization, even if at the moment foreign ministries do not realize it. For example, in the intake in which I joined the Australian Foreign Service, there was a colleague who spoke Korean and Japanese fluently but who was posted to the Middle East, even though that required him spending two years learning Arabic at the foreign ministry (and taxpayer) expense. Two other colleagues, neither of whom spoke Korean or Japanese, were sent to Seoul and Tokyo, requiring them to undertake language training as well. Of course, other considerations are taken into account in the decision to post a diplomat overseas, but without putting even an indicative price on that knowledge, very little consideration need be given to decisions that result in significant financial waste. In this particular case, sending my Japanese and Korean speaking colleague to either Tokyo or Seoul instead of the Middle East could have saved hundreds of thousands of dollars, a consideration that should form an element of the posting decision. This case and those like it are arguably just bad management decisions, but having readily available knowledge of staff members’ skills should improve decision making and is something State’s new digital tools should contribute towards.

Related examples occur when diplomats finish their postings overseas and are reassigned. Even though the foreign ministry has spent millions of dollars on the area knowledge that diplomat has acquired while abroad (via their salary, language training, housing costs, the expenses of running the Embassy, travel and other costs), because that knowledge is not priced, the organization does not realize any loss if it reassigns that individual to a completely unrelated work area. From the perspective of the organization’s bottom line, it makes no difference if the person is reassigned from Tokyo (for example) to Bagdad or sent to work on the Ethiopia desk at headquarters. In practice, when the foreign ministry makes just such a very common decision, it effectively incurs a large loss of that person’s area knowledge. Unless that person is sent back to the counterpart desk at headquarters, there is no mechanism or incentive for them to pass on any of their expertise. They will inevitably be consumed by work in their new area, and their former embassy (and the counterpart desk) will in only rare instances have anything to do with them. Foreign ministries might argue they need generalists who can adapt to a range of country and functional needs even if this comes at the cost of losing specialist expertise. But even if foreign ministries want to maintain this generalist approach, harnessing technologies and adapting management practices to facilitate better knowledge transfer, retention and retrieval makes sense.

Another major knowledge management problem faced by foreign ministries is simply knowing what expertise they actually have. This can extend to the most basic level of knowing how many speakers it has in X language and where they are physically located. Let alone more niche questions like how many Eritrean economic experts it has or how many arms control specialists.

A similar issue is identifying what the foreign ministry as a collective already knows on a subject. Foreign ministries have paper files, electronic cables, word documents, intranets, websites, emails and for some, now blogs and wikis. None of these link to each other and there is no foreign ministry equivalent of Google that lets a diplomat quickly search and scan all existing organizational written knowledge.

It all adds up to a diabolical mess. It leaves foreign ministries making irrational economic decisions, expertise that was hugely expensive to acquire being completely wasted, an organization unable to marshal its collective talent and doubling up of effort. Perhaps worst of all, because all of this waste and inefficiency is unpriced and therefore not realized, there is no value assigned to the tools that could help alleviate the problem. While the specifics might be different, all large organizations face very similar problems. The next section looks at how State is addressing this challenge.

Knowledge Management at State

Work on knowledge management began a decade ago at State with the creation of the Task Force on eDiplomacy in 2002, making it the world’s first ediplomacy unit. Since then the Task Force has been renamed the Office of eDiplomacy. Three other units at State also work predominantly in the area of knowledge management including: the Sounding Board, the Social Media Hub and CO.NX. Other important and related knowledge management areas include the SharePoint Users Group (that uses Microsoft SharePoint which allows for sharing across multiple work areas at State) and the Foreign Service Institute.

The Office of eDiplomacy began with six staff and remained near this staffing level until 2009 (p. 10). Since then it has grown sharply in size to 80 personnel, half of whom work on ediplomacy (the other half being staff from the Customer Liaison Division).

The Office’s core knowledge management work centers around several platforms it has created and operates. These include:

- Corridor: an internal professional networking site that is a hybrid of LinkedIn and Facebook, but with a stronger resemblance to the Facebook interface.

- Diplopedia: an internal Wiki, with the same look and feel as Wikipedia.

- Communities@State: an internal multi-author blogging platform.

- Enterprise Search: a search tool covering State’s unclassified intranet and some State internet websites.

- The Innovation Fund: a $2 million fund that aims to crowd source innovations from staff.

- The Virtual Student Foreign Service: a microtasking platform that taps into specialized external knowledge among university students.

In addition to these principal platforms, it also offers consultative knowledge management services via Idea Exchanges. These are described on the State Department website as follows:

eDiplomacy provides advice and support to Department organizations (domestic and abroad) to create Idea Exchanges. These online forums enable domestic and overseas employees to share and evaluate ideas for innovation and reform. The Idea Exchange program builds on the experience of The Sounding Board, an initiative launched by Secretary Clinton that encourages employees to contribute their ideas and suggestions for how to make the Department work in new, smarter, and more effective ways to advance our nation’s foreign policy goals.

The Office of eDiplomacy is also working on a range of other ways to address the knowledge management challenge at State. It is actively looking to include digital tags on all written documents that would allow officers to immediately draw together all related documents on their desktop. It is also looking at ways to identify knowledge nodes or centers of expertise. Presented visually, this would allow officers to quickly identify key internal authorities on a subject.

The Sounding Board is an attempt to source ideas and innovation directly from State Department employees. It started as a blog, but now uses ideation software (Bright Idea). It is the first thing all staff see upon logging on to State’s intranet.

The Social Media Hub, one of the Communities@State multi-author blogs, provides a range of knowledge management services, primarily to overseas posts. It runs and operates the Social Media Hub web portal, which contains detailed information for posts on best-practice use of social media, advice on the most suitable social media platforms for each market, and examples of successful applications and innovative uses by posts.

The Hub also fields specific social media queries such as on relevant State Department policies, troubleshoots social media problems such as hacked accounts, assists with compliance with legal obligations, running educational webinars and app development.

CO.NX, running on Adobe Connect, has a strong knowledge management component. It is used for training purposes, resulting in considerable savings (by eliminating airline costs or video teleconferencing fees) and internal discussions. This year the CO.NX team ran approximately 1,500 programs (up from 1,000 the year before), with the virtual speaker program now matching the in-country speaker program.

CO.NX studio, U.S. Department of State

CO.NX started with an average audience size of 30-50 people for public events. Now, for some larger ones like the Rio+20 conference it can hit close to 70,000 in a week. It has also moved from broadcasting solely from its D.C. studio to content produced by U.S. missions abroad. Around 30 missions now have their own CO.NX channels (see conx.state.gov) with most coming from Latin America.

Evaluating the effectiveness of knowledge management at State

Even though the Office of eDiplomacy has been working on knowledge management issues for a decade, the concept remains a relatively new one, even for private corporations, so much so that the World Bank, International Monetary Fund and several major U.S. corporations have approached the Office about its work.

The newness of its work means there are few established measures of its effectiveness. A mostly gushy review of the Office of eDiplomacy by the Office of Inspector General that made it sound something akin to a Silicon Valley start-up found its Knowledge Leadership team (responsible for many of the above mentioned Office of eDiplomacy platforms):

… has identified and is tracking a wide variety of metrics for its products. Output measures have been identified and, for the most part, are being tracked and reported. These measures, along with informal surveys conducted by the OIG team, indicate wide usage of and appreciation for the KL team’s knowledge management tools within the Department. However, current measures focus more on outputs than on longer term outcomes and results. eDiplomacy notes that knowledge management programs are fairly easy to measure in terms of activity; however, every peer organization, both in the government and the private sector, that ediplomacy has benchmarked against has had difficulty determining outcomes, because so much of what knowledge management must accomplish occurs at the local level. There are currently no clear, systematically collected measures of the impact of these products on Department operations. The KL team could improve these measurements by formalizing the collection of anecdotal evidence to support outcomes.

The OIG suggestion is reasonable, but clearly not a solution to the broader problem of measuring results across the department.

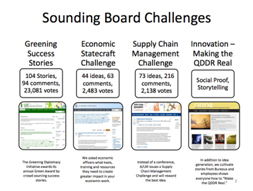

The Sounding Board also attempts to measure its impact, detailed (in part) below in two slides covering results to April 2012. These include a range of macro metrics. For example, it averages between 15,000-25,000 page views a week from internal users. Its managers count 54,736 active users, who have made 27,160 comments on 2,840 ideas submitted since February 2009. It has registered 66,986 votes and 604 subject matter expert comments.

The team has also begun tracking the status of individual ideas, providing direct feedback to State’s employees on their proposals. In April, for example, 82 ideas were completed, 17 were under consideration, 63 in the works, 64 in planning, 23 at the building block stage, 26 already at State, 41 classified as do-it-yourself, and 27 judged to be not currently feasible.

The CO.NX team has not done a detailed cost-benefit analysis (which would be a good way to justify its funding) but estimates it has saved around half a million dollars in security travel. Security technology experts now host a monthly virtual CO.NX session instead of flying to posts.

These tools are a serious effort to try to begin addressing the knowledge management challenges outlined above and each has significant potential. Diplopedia offers a platform to record and share knowledge on everything from internal processes to country facts. Communities@State provides area experts with the opportunity to share and exchange views on the latest developments. Corridor allows officers to record their expertise and for anyone to then search this. It also has the potential in future to geocode the person’s location, providing even greater utility to a globally dispersed organization. The Sounding Board aims to allow good ideas and better business processes to bypass bureaucratic bottlenecks and be dispersed quickly. CO.NX provides a means of enhancing knowledge diffusion and skills transfer by making face-to-face (virtual) training cheaper and thereby more viable. The Social Media Hub attempts to provide an easy mechanism for sharing knowledge on best practice in an area that remains unfamiliar to many and where expertise can exponentially improve impact.

These efforts to address some of the most complex institutional challenges faced by State are at the vanguard of all other foreign ministries. At the core of knowledge management, there are a few key assumptions:

- Ordinary staff (not just managers) have ideas for doing things better and are worth listening to.

- Giving managers and staff a fuller picture is worth the investment in the tools to allow this.

- Being more aware of the financial investment being made in workers’ knowledge will feed into decision making processes and reduce unnecessarily costly management decisions.

- Pooling knowledge across an organization and facilitating easy access to it improves outcomes.

In principle, State Department management has already accepted these assumptions by funding the rollout of knowledge management platforms. However, knowledge management is not yet fully baked in at State. There is a significant risk that a less visionary Secretary of State or Department Chief Information Officer could wind back gains. Even more critically than this, though, the initiatives will not survive without being able to deliver results that prove the abovementioned assumptions correct.

Formalizing the collection of anecdotal evidence as the OIG suggested is one way to supplement existing metrics. However, broader management buy-in across State also seems essential for driving cultural change. In Enterprise 2.0, McAfee writes these tools “are what Gourville calls ‘long hauls’—products that represent significant technological leaps forward and are therefore potentially quite valuable, but require major behavioral changes from their target audience” (p. 171).

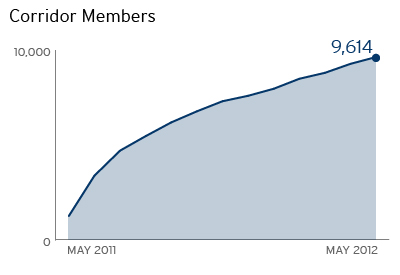

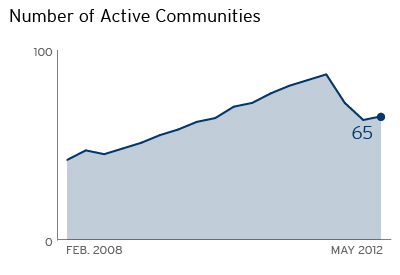

One serious risk for State (and any organization following suit) is that the platforms do not reach a critical mass of usage. Without that, the knowledge they connect employees to will be out of date or incomplete and of less use. The UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office has already experienced this issue with its internal wiki, which is currently undergoing an overhaul. The uptake of State’s knowledge applications has been strong in some areas, such as Corridor, which has grown to almost 10,000 members in under a year, and weaker in others, such as the uptake in the use of Communities@State (65 active communities, with many more social in orientation), and active contributors to Diplopedia (437 new articles in the February to May quarter).

As noted, phasing in these sorts of reforms is a long haul, but it could be accelerated and given a better chance of success through wider integration with management structures. Below are some possible ways to achieve this.

Options for Embedding Knowledge Management

One way to embed knowledge management initiatives across State would be an organizational tweak. The Office of eDiplomacy currently sits under the Chief Information Officer, Information Resource Management (IRM). The primary advantage of this placement is that it has allowed the Office of eDiplomacy to skim off what is essentially a rounding error from the Department’s IT budget to spend on innovation. However, IRM lacks clout among State’s economic and political reporting officers—the ones who write most policy-related cables—and is separated from the human resources function. For this reason, the Office of eDiplomacy could be shifted to sit under the Director General of the Foreign Service and Director of Human Resources. This makes sense in terms of providing the Office with the platform for integrating its initiatives more rapidly, building wider organizational buy-in, and because so many of its tools have direct human resources applications.

A second, related, issue is incentivizing knowledge exchange. At present, employees newly rotated out of a position have no motive to pass on their expertise, contacts and know-how to their successors. The performance structure does not reward them for making themselves easily available to their new replacement, nor incentivize other departmental experts to help them get up to speed in the shortest possible time-frame. The two-year rotation system for Foreign Service Officers adds a further complication. A reform to the performance appraisal process that gave credit to an officer (and, in particular, officers who have just left a post) for actively engaging their successor, reviewing their reports, holding regular debriefing sessions on Microsoft Communicator (allowing users to share their desktop) or CO.NX or providing guidance via Communities@State would help change this. Their bosses would also likely need to be incentivized to let their staff allocate a small part of their time to transferring their knowledge. This would have the added benefit of building a community of subject area experts.

An additional reform worth considering would be encouraging Human Resources to adopt Corridor as its central staffing platform. It could be adopted as the principal platform for recording each officer’s skills and experience, as well as the vehicle for managing all aspects of the staffing process, from posting applications to marshaling crisis response teams. It is already a far more useable tool than human resource forms, and if it were adopted as an essential platform for human resource purposes could be relied upon to be more regularly updated (and therefore accurate) than the current centralized approach. By making this general information freely available, searchable and geo-coding it, it would also greatly assist staff in quickly identifying specific (and nearby) expertise.

Speeding the integration of the platforms is another option. It is cumbersome for users to have so many different things to check: cables, emails, Corridor, Communities’ posts, Sounding Board posts, let alone external news sites. Information on these sites also needs to link together. A more seamless integration of the various platforms, which is already under discussion, could help improve usability.

Another possibility is to begin exploring basic ways to measure the knowledge held by staff. The efforts underway at the moment to try to measure knowledge nodes are steps in this direction and should help in identifying specific areas of expertise. Human resources could also begin to price some of the core foreign policy skill sets such as language skills and country knowledge. For example, it is well known how long it takes to train an individual in a given language to various levels of proficiency and so a precise cost can easily be assigned to each language at each level of competency. A registry of all staff with language skills and the equivalent value of those skills would help foreign ministries better inform staffing movements and recruitment decisions. A similar register could be developed for officers with other skills sets. For example, the cost of posting an officer to Japan for X years to cover economic issues could be used to assign a value to their Japan economic skills. This is a less precise measure of knowledge than language skills but offers a start in the right direction. As this process becomes more sophisticated and more routine, it would not only allow more rational financial decision making, but could also help make the case for investments in knowledge management tools.

Knowledge management is the least high profile of the three topics covered in this paper, but from an organizational and business perspective, the most interesting and potentially beneficial. If State is able to truly network and integrate its staffing and information systems, it will create major financial and informational awareness advantages. Of the three areas, it is also the one where ediplomacy is least baked in, making ongoing efforts to drive cultural change critical.

| « Read Part 4: Internet Freedom | Read Part 6: Conclusion and Recommendations » |

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).