Executive Summary

Jeb Bush’s higher education plan attracted little notice in the heat of a campaign that has focused more on personalities than policy details, but his proposed reforms to the federal student loan program deserve serious attention regardless of the outcome of his bid for the presidency. Bush’s plan solves many of the problems of the existing loan system and improves on the leading proposed solutions by allowing individuals to pay for their college educations based on how much they spend and how much they earn after college.

The Bush plan replaces student loans with a $50,000 line of credit that is repaid solely based on income. Students would pay one percent of their income for 25 years for each $10,000 that they access to pay for their college educations. There is no interest and total payments are capped at 1.75 times the original amount borrowed. This plan represents a significant change from existing income-driven plans, which are difficult to navigate and require participants to file onerous paperwork every year and every time their incomes change. As a result, every year hundreds of thousands of students needlessly default on their loans.

This report examines how the Bush plan would affect undergraduate students with different levels of borrowing and income, as compared to both the standard 10-year repayment schedule and the revised pay as you earn (REPAYE) income-driven repayment plan. Specifically, I compare the total repayment amounts of hypothetical borrowers with different incomes and amounts borrowed under each of the three plans. My analysis produces two main findings.

First, the total amount repaid increases much more smoothly with income under the Bush plan than under REPAYE. This is because borrowers pay a constant share of their income under the Bush plan. Low- and high-income borrowers pay more under the Bush plan than under REPAYE, whereas middle-income borrowers pay less under the Bush plan than under REPAYE.

Second, the Bush plan creates a stronger link between borrowing and repayment amounts than REPAYE. This means that the Bush plan addresses a leading concern with automatic income-driven repayment plans—that they will make students less sensitive to the prices charged by colleges and lead to further increases in tuition. For example, I find that REPAYE essentially forgives all borrowing over $30,000 for a hypothetical borrower with a starting income of $30,000. The Bush plan fixes this problem by directly tying payments to amount borrowed.

The core ideas of the Bush student loan plan are worthy of serious consideration by presidential candidates and policymakers on both sides of the aisle. Tying repayment to both income and borrowing could be accomplished in tandem with existing proposals, such as Marco Rubio’s call for income-share agreements and Rubio and Hillary Clinton’s proposals to make student loan repayment income-driven and universal.

A student lending policy that is both income- and borrowing-driven is easily adaptable to the preferences of policymakers with different political philosophies but a common desire to fix the complicated mess that our federal student loan system has become.

***

Last month, presidential candidate Jeb Bush released a higher education plan that attracted little notice in the heat of a campaign that has focused more on personalities than policy details. But Bush’s plan to reform the federal student loan program deserves serious attention regardless of the outcome of his bid for the presidency. By allowing individuals to pay for their college educations based on how much they spend and how much they earn after college, Bush’s plan solves many of the problems of the existing loan system and improves on the leading proposed solutions.[i]

Governor Bush’s plan would eliminate student loans as we currently know them, and instead offer students a line of credit of up to $50,000 that is repaid based on their income. Specifically, borrowers would pay one percent of their income for 25 years for each $10,000 that they use. The typical borrower with a four-year degree, who today takes out about $30,000 in loans, would pay three percent of her income automatically through the tax withholding system, basically eliminating defaults. There is no interest and total payments are capped at 1.75 times the original amount borrowed.[ii]

How does the Bush plan differ from current policy? Under the standard repayment plan, borrowers make fixed monthly payments that cover interest and pay down the principal over 10 years, although that period can be extended for larger loans. Borrowers also have access to a panoply of income-driven repayment programs, which tie payments to income. But these programs are confusing and difficult to navigate, requiring participants to file onerous paperwork every year and every time their incomes change.[iii] As a result, hundreds of thousands of borrowers needlessly default on their loans every year.[iv]

In this report, I examine how the Bush plan would affect undergraduate students with different levels of borrowing and income, as compared to both the standard 10-year repayment schedule and the revised pay as you earn (REPAYE) income-driven repayment plan. Under REPAYE, participating borrowers pay 10 percent of their discretionary income (defined as income minus 150 percent of the federal poverty level) for 20 years. Interest continues to accumulate on the loan, but any remaining balance after 20 years is forgiven.[v]

The Bush plan also ties payments to income, but the percentage of income rises with the amount borrowed and there is no interest. There is no “income offset” of 150 percent of the poverty line, but the percentage of income paid is lower (1-5 percent for up to 25 years) than under REPAYE (10 percent for up to 20 years). The Bush plan caps total payments at 1.75 times the original amount, whereas REPAYE forgives any remaining balance at the end of the repayment period.[vi]

I compare the total repayment amounts of hypothetical undergraduate borrowers with different incomes and amounts borrowed under the Bush and REPAYE plans (as well as the standard plan, where payments do not depend on income). This exercise requires making a number of assumptions. Specifically, I assume:[vii]

- Income increases by four percent (in nominal terms) every year

- REPAYE and standard repayment are subject to the current interest rate of 4.29 percent[viii]

- Borrowers are in single-person families, and the corresponding federal poverty level of $11,880 increases by two percent every year due to inflation

- Borrowers have a personal discount rate of three percent, and all repayment totals are discounted to the present[ix]

The last assumption sounds like a technical one, but it is very important in practice. A discount rate is a measure of how much people value money tomorrow compared to money today. A three percent rate assumes that borrowers are as happy receiving a dollar a year from now as they are receiving 97 cents today. This is important because the three percent adds up over longer periods of time. For example, $30,000 divided into 10 yearly payments of $3,000 has a present value of $25,591. But if it is paid over 30 years at $1,000 per year, the present value is only $19,600. This difference reflects the assumption embedded in the discount rate that people prefer to pay money farther in the future.[x]

Discounting is important because it enables analysts to make better comparisons between policy proposals that involve making payments over different periods of time: 10 years under the standard repayment plan, up to 20 years under REPAYE, and up to 25 years under the Bush plan. For example, a borrower of $30,000 with a starting salary of $50,000 makes total (undiscounted) payments of $37,523 under the standard 10-year plan and $52,500 under the Bush plan. But the payments under the Bush plan are spread out over a much longer period of time with no interest (23 years before the 1.75 cap is reached). As a result, the present values of the two series of payments are about the same ($32,008 under 10-year repayment and $32,935 under the Bush plan).

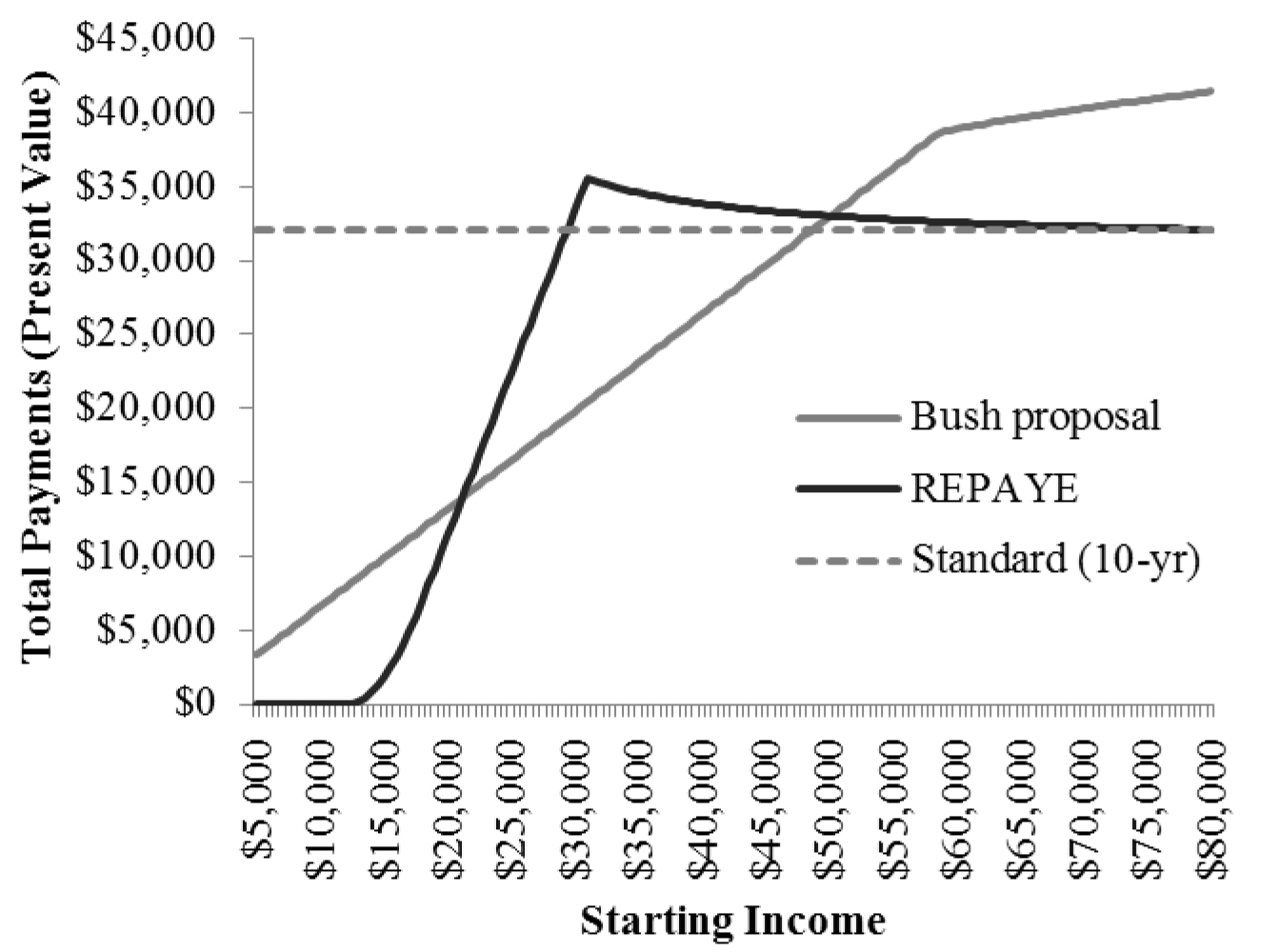

My first main finding is that the amount repaid increases much more smoothly with income under the Bush plan than under REPAYE. Figure 1 shows the total (discounted) payments for different starting incomes, all for a hypothetical borrower of $30,000.[xi] Low- and high-income borrowers pay more under the Bush plan than under REPAYE, whereas middle-income borrowers pay less under the Bush plan than under REPAYE. This is the direct result of the policy design features described above.

Figure 1. Total payments vs. starting income for hypothetical borrower of $30,000

Under REPAYE, borrowers with very low incomes pay nothing because they make less than 150 percent of the poverty level for 20 years and then have the balance forgiven. Starting at roughly $15,000 of income, total payments increase rapidly because the additional income is subject to the 10 percent repayment rate and the amount of forgiveness declines. But once income reaches about $30,000, total payments are approximately flat because borrowers no longer receive forgiveness and thus income only affects whether REPAYE participants finish making payments earlier or later.

The payment-income relationship is much smoother under the Bush plan. Borrowers with higher incomes pay more because they are paying a constant share of their income (three percent in this example). There is a bend in the line at approximately $60,000 of income, as this is where the 1.75 cap kicks in (recall that borrowers pay no more than 1.75 times the original amount). However, higher income above that point means paying the maximum amount earlier rather than later. In present value terms, this means a higher total payment.

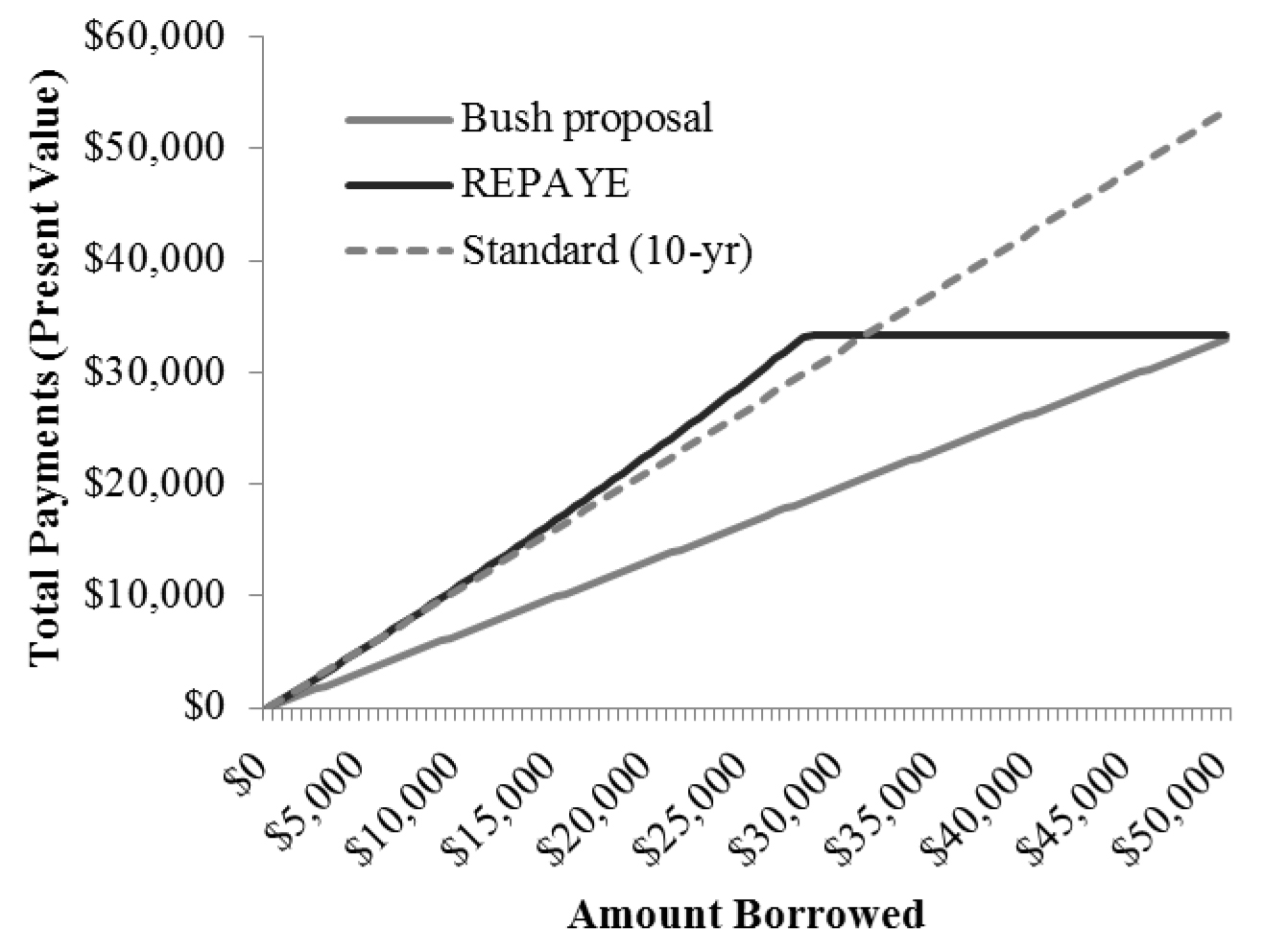

My second finding is that the Bush plan creates a stronger link between borrowing and repayment amounts than REPAYE. Figure 2 shows the total (discounted) payments of hypothetical borrowers of different amounts, assuming a starting income of $30,000.[xii] Under the Bush plan, more borrowing means more payments because the percentage of income paid is directly tied to the amount borrowed. But under REPAYE, that is only true until about $30,000, above which additional borrowing results in no additional payments because the percentage of income paid is unrelated to borrowing and the additional borrowing is forgiven.[xiii]

Figure 2. Total payments vs. amount borrowed for hypothetical borrower with starting income of $30,000

This finding is important because a leading concern with automatic income-driven repayment plans is that they will make students less sensitive to the prices charged by colleges and lead to accelerated tuition inflation. In the example above, the hypothetical student doesn’t pay back any of the extra borrowing over $30,000.[xiv] The Bush plan fixes this incentive problem by directly tying payments to amount borrowed (in addition to income).

This analysis suggests that the Bush plan offers a number of improvements over existing income-driven repayment plans, as well as proposals that would make some version of the current IDR plans automatic. But it is important to emphasize that none of the features of existing proposals are set in stone. For example, the Bush plan could be revised to include an income offset (such as some percentage of the federal poverty level) that would allow very low-income borrowers to make no payments. Alternatively, the REPAYE plan could be revised yet again (and renamed REREPAYE) to eliminate some of its unintended consequences, such as the weak link between amount borrowed and amount repaid.

But the Bush plan has the great advantage of putting the income-driven nature of payment for college at the center of the plan rather than embedding it in a set of complicated and confusing repayment plans. Students would know at the point of borrowing that they were committing to repay a given percentage of their income for up to 25 years, rather than taking on a debt balance that they may or may not know can be repaid based on their incomes in their future.

For this reason, the core ideas of the Bush student loan plan are worthy of serious consideration by presidential candidates on both sides of the aisle and by policymakers working on the overdue reauthorization of the Higher Education Act. Additional analysis is needed to assess both the loan and the non-loan components of competing higher education plans, especially the costs of these plans to taxpayers. Other components of the Bush plan include the elimination of most federal borrowing for graduate school (due to the $50,000 limit) and making Pell grants to low-income students easier to access (by eliminating the FAFSA). The total cost of the plan is unclear, in part due to the uncertainty about who would participate.

Tying repayment to both income and borrowing could be accomplished in tandem with candidates’ existing proposals. Marco Rubio has been a longtime supporter of automatic income-driven repayment, and could improve his proposal using elements of the Bush plan. Rubio is also a supporter of income-share agreements, which are a private-sector analog of the Bush plan.[xv] He could propose the public version for college and a private-sector version focused on the financing of graduate education.

Hillary Clinton agrees with Bush and Rubio on the need for making student loan repayment income-driven and universal.[xvi] Clinton could propose a version of the Bush plan that retains its progressivity at the middle and higher income levels, and makes it more progressive at the bottom by adding an income offset. She could also expand it to higher borrowing levels that would better accommodate graduate students.

Our student loan system is a complicated mess in many ways. Fixing it should be a priority for Congress and the next president. The evidence presented above suggests that Governor Bush’s plan is a promising starting point for any policymaker serious about higher education reform.

***

Addendum: After this report was published, the Bush campaign brought to my attention a (previously unpublished) detail of their plan, which is that borrowers who qualify for the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) have their payments suspended in an amount equal to 15 percent of the value of their EITC. This means that low-income borrowers will repay less under the Bush plan than is indicated by my analysis.

[i] Disclosure: Governor Bush previously chaired the advisory board of the Program on Education Policy and Governance at Harvard University, with which I have been affiliated for many years. Additionally, I know a number of the informal advisors who worked on his higher education plan.

[ii] This report is focused on the student loan component of the plan. For description and analysis of the broader plan, see https://jeb2016.com/education/?lang=en, http://www.nationalreview.com/article/429921/jeb-bush-higher-education-reform-financing-college-tuition, and https://www.brookings.edu/blogs/social-mobility-memos/posts/2016/01/18-what-can-jeb-plan-do-higher-education-akers.

[iii] https://www.brookings.edu/research/papers/2016/01/07-student-loans-low-earnings-dynarski

[iv] https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2015/10/01/student-loan-defaults-drop-obama-admin-again-tweaks-rates

[v] Under current law, loan forgiveness is treated as taxable income. For the purpose of this analysis, I assume that this law will be changed given that borrowers who qualify for forgiveness will generally be unable to pay the tax on the forgiven balance.

[vi] The Bush plan is technically equivalent to an automatic income-driven repayment plan with a 75 percent origination fee, no interest, no early repayment, and (tax-free) forgiveness after 25 years.

[vii] Additionally, my analysis calculates repayment on an annual (rather than monthly) basis for simplicity. This should not alter any of the qualitative conclusions.

[viii] I ignore origination fees, which are currently applied to federal student loans. I also ignore the interest benefits in REPAYE.

[ix] A discount rate of three percent is typical in the retirement planning literature (http://www.hks.harvard.edu/pepg/PDF/Papers/PEPG13_01_West.pdf). I obtain qualitatively similar findings using discount rates of five and seven percent.

[x] In my analysis, total discounted payments made under programs that include interest (i.e. standard repayment and REPAYE) are lower if they are paid off sooner because the assumed discount rate (3 percent) is lower than the interest rate (4.29 percent).

[xi] Changing the amount borrowed (e.g., to $10,000 or $50,000) shifts the location of the bend points in Figure 1, but does not change the overall shape of the curves.

[xii] Changing the assumed income shifts the location of the REPAYE bend point in Figure 2. For a sufficiently high income, the bend point would be above the maximum amount that can be borrowed under the Bush plan ($50,000).

[xiii] Jason Delisle and Alexander Holt call this the “zero marginal cost” threshold, which is especially relevant for graduate student borrowers given the higher amounts of borrowing typically involved (https://www.newamerica.org/downloads/ZeroMarginalCost_140910_DelisleHolt.pdf).

[xiv] This is not particularly relevant for dependent undergraduate borrowers, for whom maximum lifetime borrowing is capped at $31,000. But for the independent borrowers the maximum is $57,500 and for graduate students it is essentially unlimited (https://studentaid.ed.gov/sa/types/loans/subsidized-unsubsidized#how-much). The Bush plan caps borrowing at a combined $50,000 for undergraduate and graduate school.

[xv] https://marcorubio.com/issues-2/marco-rubio-position-higher-education-policy-college/

[xvi] https://www.hillaryclinton.com/briefing/factsheets/2015/08/10/college-compact-costs/

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).