This report from The Brookings Institution’s Artificial Intelligence and Emerging Technology (AIET) Initiative is part of “AI Governance,” a series that identifies key governance and norm issues related to AI and proposes policy remedies to address the complex challenges associated with emerging technologies.

Artificial intelligence (AI) is “summoning the demon,” Elon Musk warned, continuing a great tradition of fearful warnings about new technology. In the 16th century, the Vicar of Croyden warned how Gutenberg’s demonic press would destroy the faith: “’We must root out printing or printing will root us out,’ the Vicar told his flock.”1 Preceding Musk’s invocation of the devil by a couple of centuries, an Ohio school board declared the new steam railroad technology to be “a device of Satan to lead immortal souls to hell.”2 Others warned of secular effects: The passing of a steam locomotive would stop cows from grazing, hens from laying, and precipitate economic havoc as horses became extinct and hay and oats farmers went bankrupt.3 Only a few years later, demonic fears appeared once again when Samuel Morse’s assistant telegraphed from Baltimore suggesting suspension of the trial of the first telegraph line. Why? Because the city’s clergy were preaching that messages by sparks could only be the work of the devil. Morse’s assistant feared these invocations would incite riots to destroy the equipment.4

We chuckle at these stories now, but they were once the manifestation of very real fears about the dangers of new technologies. They echo today in our discussions regarding the dangers of artificial intelligence. As evidenced by Musk’s concerns as well as those of other prominent individuals, there are many fears that AI will, among other things, impoverish people, invade their privacy, lead to all-out surveillance, and eventually control humanity.

“As we consider artificial intelligence, we would be wise to remember the lessons of earlier technology revolutions—to focus on the technology’s effects rather than chase broad-based fears about the technology itself.”

In assessing the reality of these claims, it is instructive to look to the lessons of history. Experience with new technologies teaches us that most inventions generated both good and bad results. They were classic “dual-impact” products that helped people at the same time they created harms. As I argue in this paper, a crucial variable in mitigating possible harms was the policy and regulatory response to counteract negative ramifications of the new technology. As we consider artificial intelligence, we would be wise to remember the lessons of earlier technology revolutions—to focus on the technology’s effects rather than chase broad-based fears about the technology itself.

Fear as a substitute for thinking

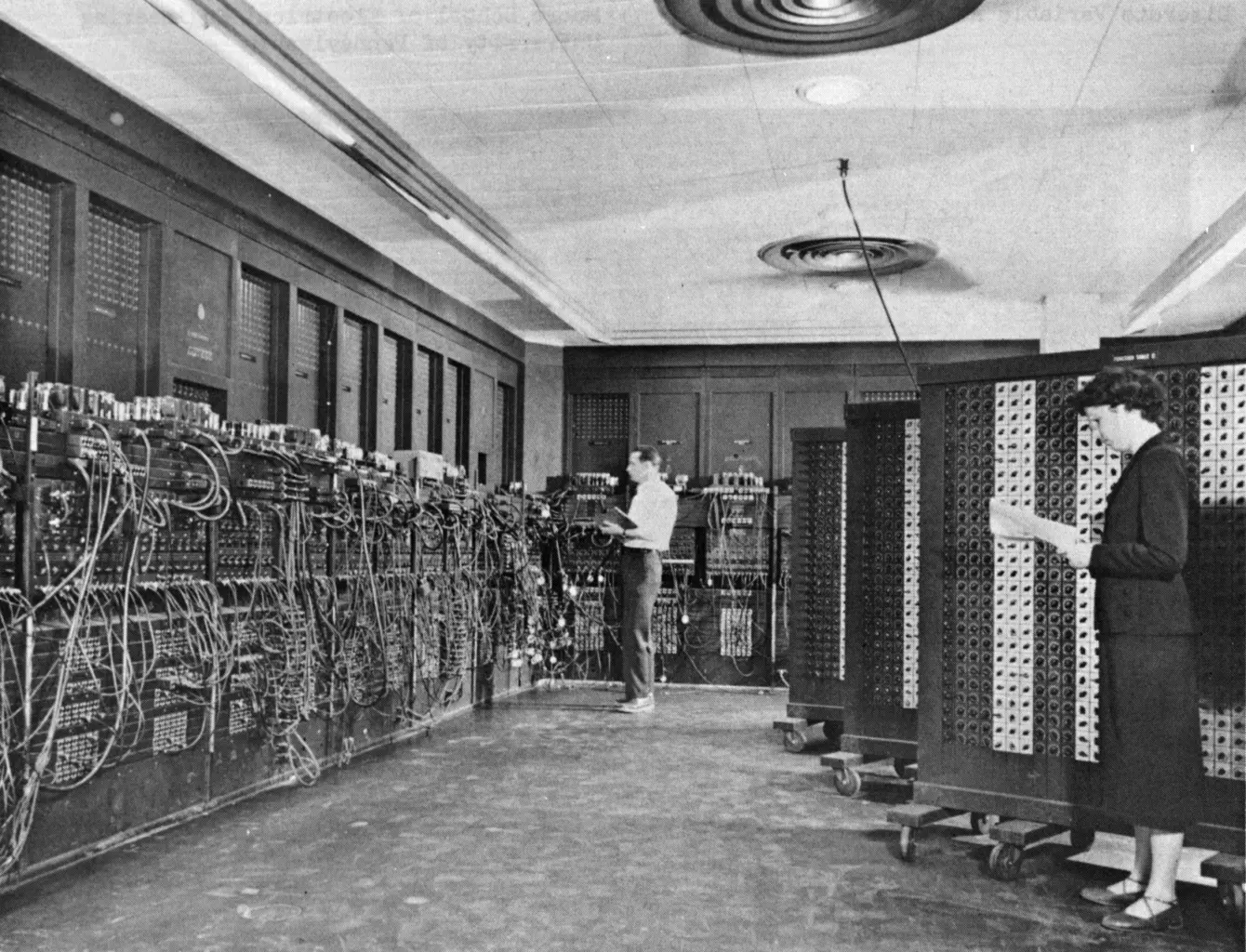

In the mid-19th century, British mathematician Charles Babbage conceptualized the first computer. The idea that God-given human reason could be replaced by a machine was fearfully received by Victorian England in a manner similar to today’s concern about machines being able to think like humans. In both instances, the angst, while intellectually interesting, proved to be overwrought. Babbage’s computer, detailed in hundreds of pages of precise schematics, was never fully constructed. Similarly, research to create human-like AI is not progressing with the feared apocalyptic pace. “We’ve pretty much stopped trying to mirror human thinking out of the box,” explains Andrew Moore, former dean of computer science at Carnegie-Mellon University.

At the forefront of history’s lessons for today’s technology challenges is the imperative to avoid substituting fear in place of solution-oriented thinking that asks questions, identifies issues, and seeks solutions. If thinking machines are not on the horizon to pose an existential threat, then how do we move beyond hysteria to focus on the practical effects of machine intelligence?

“At the forefront of history’s lessons for today’s technology challenges is the imperative to avoid substituting fear in place of solution-oriented thinking that asks questions, identifies issues, and seeks solutions.”

While the idea of artificial intelligence can be intimidating, in practical effect, machine learning is effectively coming to describe all of computer science. It is difficult to discover activity in the field of computer science that is outside of machine learning’s manipulation of data. Over a relatively condensed period, intelligent machines have moved from science fiction into our everyday lives. Importing the fears that confronted Babbage in the Victorian era does little to advance consideration of 21st-century policy decisions.

Elon Musk calls for “[r]egulatory oversight, maybe at the national and international level, just to make sure that we don’t do something foolish.” It is an idea validated by history. As the Industrial Revolution transformed the Western world’s economy and the lives of its citizens, it became apparent that the marketplace rules that had worked for agrarian mercantilism were no longer adequate for industrial capitalism. When the interests of the industrialists clashed with the broader public interest, the result was a new set of rules and regulations designed to mitigate the adverse effects resulting from the exploitation of the new technologies.

The call to similarly come to grips with AI is a legitimate effort. But it is a simple goal with complex components. The first response to such a suggestion is: “What AI are you talking about?” Is the suggestion to regulate AI weaponry? Or its impact on jobs? Is it AI’s impact on privacy? Or its ability to manipulate the competitive marketplace? Is it a suggestion to regulate the machines that drive AI? Or is it to control the activities of the people who create the AI algorithms?

The first step in any such oversight, therefore, is a clear delineation of the problems to be addressed. Regulating the technology itself is like regulating the wind: It blows to bend everything it touches but cannot be captured. Rather than the regulation of the amorphous mashup of technologies we refer to as artificial intelligence, we should focus on how to stormproof our dwellings and deal with the effects of the new technology.

Look past the specific technology to its effects

A key lesson of history is that effective regulation focuses on prioritizing the effects of the new technology, rather than the ephemeral technology itself. The transformational nature of a new technology is not per se the primary technology itself, but rather the secondary effects enabled by that development. We didn’t regulate the railroad tracks and switches; we regulated the effects of their usage, such as rates and worker safety. We didn’t regulate the telegraph (and later telephone) wires and switches, but whether access to them was just and reasonable. History’s road map is clear: If there is to be meaningful regulation of AI, it should focus on the tangible effects of the technology.

Two factors make such regulation particularly challenging. One is the vast breadth of AI’s reach. The ability to rapidly access and process vast quantities of data will drive our cars, fly our planes, cook in our kitchens, conduct research without laboratories and test tubes, and manage everything from our homes to how we conduct war. Here is where the industrial regulatory model runs into difficulty. Previously, effect-based regulation could be centralized in a purpose-built agency or department. The applications of AI will be so pervasive, however, that its oversight must be equally pervasive throughout all the activities of government at all levels—with an agility not normally associated with the public sector.

The other challenge to regulating AI is the speed of its advancement. Until recently, the slow evolution of technology afforded a time buffer in which to come to grips with its changes. The spindle, for instance, was a hallmark of the first Industrial Revolution, yet it took almost 120 years to spread outside Europe. At such a pace, society, economic activity–and regulation–had time to catch up. In place of history’s linear technological progress, however, AI’s expansion has been described as “exponential.” Previously, time allowed the development of accountability and regulatory systems to identify and correct the mistakes humans make. But under the pressure of the exponential expansion of machine learning, we are now confronted with dealing with mistakes that machines make, whether it is flying a 737 or prejudicing analytical analysis.

Our history is clear: In a time of technological change, it is the innovators who make the rules. This should not be surprising, since it is they who see the future while everyone else is struggling to catch up. But history is also clear that such a situation exists only until the innovators’ rules begin to infringe on the public interest, at which time governmental oversight becomes important. Regulation is about targeting the effects of the new technology, determining acceptable behavior, and identifying who oversees those effects.

“Our history is clear: In a time of technological change, it is the innovators who make the rules.”

Effective regulation in a time of technological change is also about seeking new solutions to protect old principles. Our challenge in response to AI is the identification of the target effects, development of possible remedies, and structuring of a response that moves beyond industrial remedies to the data-driven AI challenge itself. The metamorphosis into an AI-based economy will be a challenge as great as the challenge 150 years ago of adapting an agrarian economy to industrial technologies.

While the list of AI-driven effects is seemingly boundless, there are at least two effects that reprise issues of the Industrial Revolution: the exploitation of new technology to gain monopoly power, and automation’s effect on jobs.

The capital asset of the 21st century

The Industrial Revolution was built on physical capital assets, such as coal or iron, that could be manufactured into new assets from building girders to sewing machines. The AI revolution, in contrast, is built on a non-physical asset: digital information. Pulling such information from various databases and feeding it into an AI algorithm produces as its product a new piece of data.

“Like the industrial barons of the 19th and 20th centuries, the information barons of today seek to monopolize their assets. This time, however, the monopoly has more far-reaching effects.”

By one estimate, about half of this new capital asset is personal information. The internet has created a new digital alchemy that transforms an individual’s personal information into a corporate asset. Like the industrial barons of the 19th and 20th centuries, the information barons of today seek to monopolize their assets. This time, however, the monopoly has more far-reaching effects. The consequence of a Rockefeller monopoly of oil or a Carnegie monopoly of steel was control over a major sector of the economy. The consequence of monopoly on the collection and processing of data not only puts the information barons in control of today’s online market, but also in control of the AI future by controlling the essential data inputs required by AI.

As mystical as artificial intelligence may sound, it is nothing more than algorithmic analysis of enormous amounts of data to find patterns from which to make a high percentage prediction. Control of those input assets, therefore, can lead to control of the AI future. Of course, monopolistic control of capital assets is nothing new. Historically, bringing the application of those assets into accord with the public interest has been a pitched battle. The results of previous such battles have been not only the protection of competitive markets, consumers, and workers, but also the preservation of capitalism through the establishment of behavioral expectations. Reaching an equivalent equilibrium when a handful of companies control the capital asset of the 21st century will be similarly hard fought.

AI and human capital

Another import from history is concern about the effect of automation on human capital. In the 19th century, when automation eliminated many of the farm jobs that had been the backbone of local economies, the former farm workers simply moved to the city and learned the rote jobs of factory workers. Such mobility was less available in the 20th century. The so-called “Automation Depression” of the late 1950s was attributed to “the improved machinery [that] requires fewer man-hours per unit of output,” but without the safety net of the worker’s ability to move to a new endeavor. Responding to effects such as this, President John F. Kennedy described machine displacement of workers as “the major domestic challenge of the ‘60s.”

In the information era, artificial intelligence and machine learning have similarly eliminated jobs, but they have also created jobs. ATMs eliminated the jobs of bank tellers, for instance, but bank employment is up because the savings was used to open new branches that required more trained customer service representatives. “The big challenge we’re looking at in the next few years is not mass unemployment but mass redeployment,” Michael Chui of the McKinsey Global Institute has observed. The AI-driven challenge, therefore, is to equip individuals with the skills necessary for information era redeployment: technical competence to interface with smart machines and the critical thinking and judgment capabilities those machines lack.

The Industrial Revolution’s demand for an educated workforce fostered a revolution in public education. Using factory-like methods, young raw material was fed into an educational process that 12 years later produced an employable individual with the math and reading skills necessary to understand the shop floor manuals. Such a basic level of knowledge allowed mobility among basic-skills jobs. If you lost your job making buggy whips, for example, your basic skills still worked at the automobile factory. The difficulty today is that those kinds of repetitive jobs are being turned over to AI. We run the risk of “preparing young people for jobs that won’t exist,” according to Russlynn Ali, CEO of the education nonprofit XQ Institute.

When Randall Stevenson, CEO of AT&T, told his workforce that those who don’t spend five to 10 hours a week learning online “will obsolete themselves with technology,” he identified a new educational paradigm for the information economy. “There is a need to retool yourselves, and you should not expect it to stop,” was his prescription. When it comes to human capital, oversight of AI’s effects extends to an education system that is geared to the skills necessary to exist and prosper in a smart world.

The right to a future

Defining the new technology in terms of its effects, and structuring policies to deal with those effects, allows us to move beyond the kind of demonic fear that historically characterized new technology. But it does not dispose of citizens’ concerns of adverse consequences to their future—especially their economic future.

Today’s politically explosive angst about immigration is not only an expression of fear about intelligent technology, but also about whether leaders care enough to do something about it. In historical perspective, it echoes the last time automation made people worry about their future employability. As industrial technology displaced workers in the 19th century, anti-immigrant sentiment was fueled by fear: “They’re coming to take our jobs.” In the 21st century the fear is now, “They’re automating to take our jobs.” Harvard Professor Jill Lepore has observed, “Fear of a robot invasion is the obverse fear of an immigrant invasion. … Heads, you’re worried about robots; tails, you’re worried about immigrants.”

“Societies impose government oversight for the protection of old principles in a time of new technology. Foremost among those principles is each individual’s right to a future.”

Societies impose government oversight for the protection of old principles in a time of new technology. Foremost among those principles is each individual’s right to a future; and it comes in multiple manifestations. In the educational realm, it means adequate training to be meaningfully employed. Economically, it means maintaining the benefits of capitalism through checks on its inherent incentive to excess.

Most importantly, the right to a future begins with the belief that there is a future, and that national leaders care about whether individuals affected by new technologies participate in that future.

The new technology lessons of history are grounded in two messages: Don’t panic and don’t stand still. The experiences with technological innovations of the past have taught us that we can be in control if we will assert ourselves to be in control.

The Brookings Institution is a nonprofit organization devoted to independent research and policy solutions. Its mission is to conduct high-quality, independent research and, based on that research, to provide innovative, practical recommendations for policymakers and the public. The conclusions and recommendations of any Brookings publication are solely those of its author(s), and do not reflect the views of the Institution, its management, or its other scholars.

Microsoft provides support to The Brookings Institution’s Artificial Intelligence and Emerging Technology (AIET) Initiative, and AT&T provides general, unrestricted support to the Institution. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions in this report are not influenced by any donation. Brookings recognizes that the value it provides is in its absolute commitment to quality, independence, and impact. Activities supported by its donors reflect this commitment.

-

Footnotes

- Tom Wheeler, From Gutenberg to Google: The History of Our Future (Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press, 2019), 4.

- Christian Wolmar, Blood, Iron, and Gold: How the Railroads Transformed the World, First edition (New York: PublicAffairs, 2010), 78.

- John F. Stover, The Routledge Historical Atlas of the American Railroads, Routledge Atlases of American History (New York: Routledge, 1999), 44.

- Tom Standage, The Victorian Internet: The Remarkable Story of the Telegraph and the Nineteenth Century’s on-Line Pioneers (New York: Walker, 2007), 52.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).