Content from the Brookings Doha Center is now archived. In September 2021, after 14 years of impactful partnership, Brookings and the Brookings Doha Center announced that they were ending their affiliation. The Brookings Doha Center is now the Middle East Council on Global Affairs, a separate public policy institution based in Qatar.

Since signing the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), the EU/E3 – the EU, Germany, France, and the UK – have pursued rapprochement with Iran. Since the U.S. withdrawal, the future of the JCPOA has been in jeopardy. This policy briefing provides a critical review of Europe’s policy of rapprochement with Iran. It contends that EU policy on Iran must address two crises: first, a U.S. policy toward Iran that contrasts with the one pursued by Europe, with the transatlantic powers working at cross-purposes and, second, an Islamic Republic that faces an acute crisis at home. This briefing suggests Europe should cooperate with Washington over Iran policy, acting as a corrective. Vis-a-vis Tehran, Europe must pursue a dual strategy of continued cooperation while using its leverage to encourage Iranian course corrections. Such an Iran policy would couple pragmatism with idealism as enshrined in the EU Global Strategy.

Key Recommendations

- Keep the JCPOA alive for two reasons: (1) Containing the Iran nuclear program would help prevent a nuclear arms race in the Middle East; (2) Maintaining the JCPOA ensures that the EU will retain leverage over Iran, which would otherwise dissipate if the deal completely falls apart.

- Engage Washington: A transatlantic Iran policy should not be buried because concerns over Iranian policy are likely to outlive the Trump Administration. Yet the EU should simultaneously pursue the project of strengthening its autonomy from Washington’s Iran policy.

- Use the EU’s leverage with Iran, cognizant of its comparative advantages: The EU should not shy away from introducing conditions for cooperation. Taking a steadfast approach, the EU will present an important driver for Tehran to start changing its behavior. Despite Tehran’s official refusal to engage with Brussels over domestic issues and its regional role, a genuine concern over domestic economic instability will encourage it to accept the EU’s promotion of gradual changes.

- Avoid pro-regime favoritism: The EU needs to take a clear stance in line with its own values and in support of the Iranian people’s democratic rights. Leaving the scene to the United States would play into the hands of the regime’s repressive apparatuses. The EU must use its relations with various sections of Iran’s elite, signaling to them that state repression will negatively impact its economic and political engagement and support.

- Initiate an overdue paradigm shift toward harmonizing foreign and development policies for the sake of sustainable stability: The authoritarian stability and neoliberal economic policies of the past have failed to produce stability in Europe’s neighborhood, including Iran. The EU must now prepare the conceptual grounds for a paradigm shift in its foreign policy.

Introduction

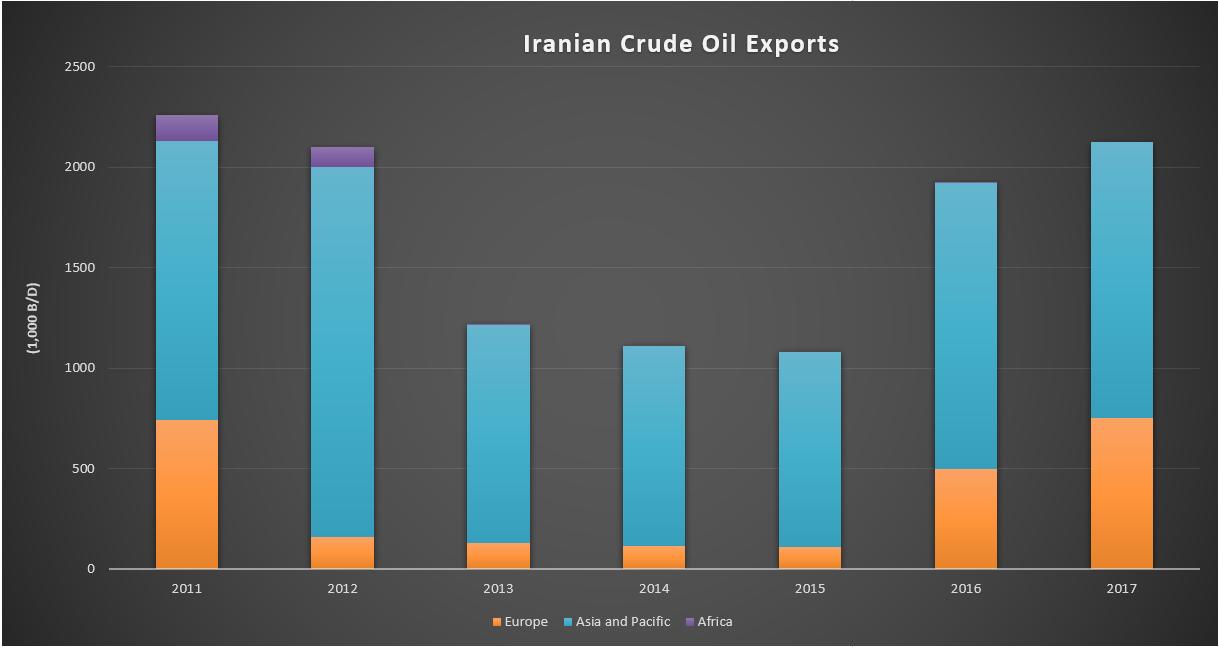

U.S. President Donald Trump’s unilateral withdrawal from the JCPOA on May 8, 2018, followed by Secretary of State Mike Pompeo’s May 21 address on a new Iran policy, has called into question the viability of that multilateral agreement. This development poses an immense challenge to Europe’s policy of cooperation and rapprochement with Iran.1 Pompeo has made twelve maximalist demands, calling on Iran to end its nuclear and ballistic missile programs and to cease regional meddling. This has been accompanied by regime change rhetoric and a public relations campaign questioning the Islamic Republic’s legitimacy.2 Yet the administration insists that it only seeks to change the regime’s behavior.3 At the core of Washington’s maximum pressure strategy toward Tehran stands the re-imposition of U.S. extraterritorial sanctions in two rounds; in early August and more importantly in early November 2018 targeting Iran’s oil exports (see Figure 1) and its central bank.

Figure 1: Iranian Crude Oil Exports

The economic impact of the U.S. sanctions started unfolding even before their re-imposition. Many European companies and financial institutions have been forced to halt their Iran activities while the Iranian national currency has spiraled downwards.

With U.S. sanctions already taking a heavy toll on Iran’s crisis-ridden economy, there is still uncertainty about the end game of the Trump administration’s maximum pressure strategy; is it seeking the regime’s collapse or forcing it to change its behavior through an aggressive containment policy to limit its offensive capabilities, ultimately bringing it closer to bowing to U.S. demands? President Trump’s July 2018 offer to strike a new deal with Tehran without preconditions suggests that the latter might be pursued.4 But this willingness stands in contrast to his secretary of state’s twelve demands, making it hard for the Iranian leadership to enter into public talks while saving face. However, despite Iran’s Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei’s rejection of talks,5 they cannot be excluded given the heavy and comprehensive impact of U.S. sanctions. Indeed, Tehran is left with little benefit of what remains from the JCPOA, at a time of acute domestic crisis.6 Oman and Switzerland might provide back channels for such talks.7

Washington’s new Iran policy might indeed be intended to provoke Tehran to leave the JCPOA and to force it into accepting a new deal. However, Iran abandoning the JCPOA might only be the case under special circumstances, as such a material breach of the accord would abrogate the U.N. Security Council resolution that suspended international sanctions.8 U.N. sanctions would be snapped back, while Tehran would lose the support of the remaining partners to the agreement (EU, Russia, and China).

Since 2017, the Islamic Republic of Iran has entered the most acute crisis in its history. The 2017/2018 revolt and ongoing protests have resulted from interrelated socioeconomic, political, and environmental challenges, reaching an unprecedented climax. The new U.S. strategy is likely to deepen Iran’s internal crisis, at the same time helping to fuel Tehran’s authoritarianism.9 While the chances of Iran abiding by Pompeo’s demands regarding its regional policies is close to nil,10 the unprecedented crisis at home and dwindling resources might pave the way for Iranian compromises.

Meanwhile, Europe has pledged its intention to save the JCPOA and has expressed opposition to the new U.S. policy on Iran. However, it cannot ignore that Washington’s maximum pressure policy challenges its own Iran policy of cooperation and rapprochement. Against this backdrop, the EU’s Iran policy must address these two fundamental challenges: the new direction of U.S. policy, as well as Iran’s unprecedented domestic crisis.

Europe and Iran: The EU’s interests, strengths, and limitations

The EU’s interests pertaining to Iran are (1) to maintain stability in the Persian Gulf region, which continues to be vitally important for global oil supplies and prices; (2) to resolve the conflicts in the Middle East, not least in order to prevent further refugee movements toward Europe in the wake of instability and failing states; (3) to diversify its energy supplies by increasing Iranian imports and reducing Europe’s significant energy dependence on Russia; and (4) to boost exports of its industrial goods by expanding economic relations with Iran at a time of weak European growth rates over the past decade.

In its dealings with the Gulf region, the EU Global Strategy, published a year after the signing of the JCPOA, advocates a balanced engagement:

The EU will continue to cooperate with the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) and individual Gulf countries. Building on the Iran nuclear deal and its implementation, it will also gradually engage Iran on areas such as trade, research, environment, energy, anti-trafficking, migration and societal exchanges. It will deepen dialogue with Iran and GCC countries on regional conflicts, human rights and counter-terrorism, seeking to prevent contagion of existing crises and foster the space for cooperation and diplomacy.11

However, these policy aims, for the most part, do not reflect the objectives espoused publicly by many European policymakers, who believe that engaging in trade and rapprochement with Iran should contribute to facilitating change there.

The strengths of Europe’s relationship with Iran lie in the central role it has played in the modernization of Iran’s industrial infrastructure, in the good reputation it enjoys across the Islamic Republic’s political spectrum, and in its substantial role in helping Tehran improve its standing in the international system.12 Importantly, Europe must recognize that it is the only power that can provide Iran with the economic benefits it seeks.13 These comparative advantages relative to other non-Western great-powers in fact constitute the EU’s leverage in its relations with Tehran.

Iran can hardly afford to lose Europe

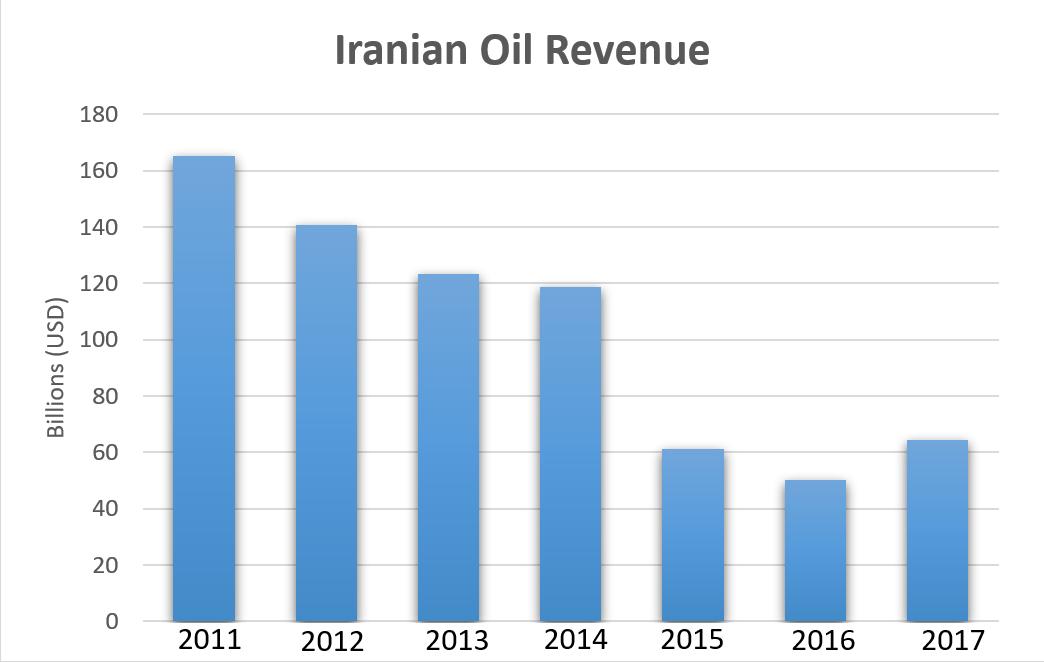

Although Washington’s new tough line on Iran has emboldened hardline circles in Iran opposed to the JCPOA, there is a willingness at the top of the IRI to keep the deal alive. On May 23, Iran’s Supreme Leader demanded from Europe six concrete guarantees. They include increasing EU oil imports from Iran to compensate for re-imposed U.S. sanctions, while not raising the issue of Iran’s ballistic missile program and regional policies.14 Khamenei’s expressed concern about the loss of oil export revenues (see Figure 2), especially in a context of acute economic crisis at home,15 coupled with his stated intention to remain in the JCPOA with the EU’s help, signals that the Islamic Republic needs Europe in its own right, as well as to help offset U.S. pressure. The latter point remains a long-held policy of post-revolutionary Iran.

Figure 2: Iranian Oil Revenue

The EU and the Trump administration: On the necessity of a transatlantic Iran policy

The gulf between the EU and U.S. positions toward Iran might appear unbridgeable. Although it is not easy to imagine transatlantic cooperation over Iran to emerge from the ashes of Washington’s hard exit from the JCPOA and the maximalist demands toward Tehran, there are several factors compelling both sides to find a modicum of common ground.

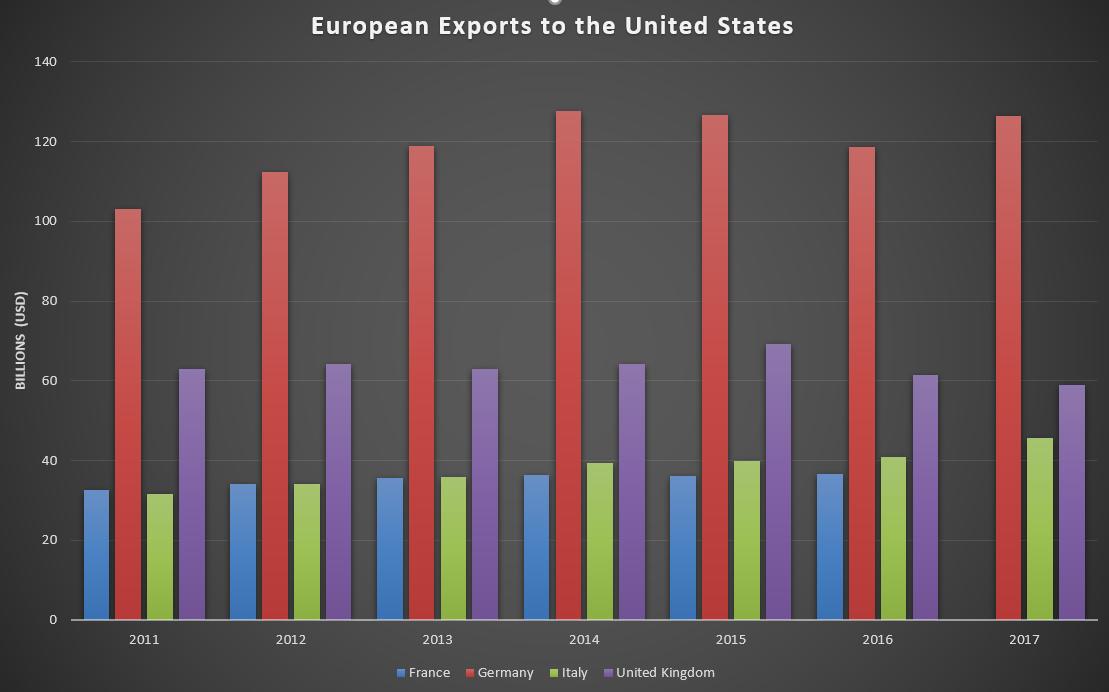

The EU, despite its stated aim to chart its own course on Iran policy, cannot afford to ignore U.S. policy. There are important reasons for this: (1) Economically, the re-imposition of U.S. sanctions will detract European economic engagement with Iran, given U.S. dominance in the international financial system and the dwarfing of the EU’s business relations with Iran in comparison to those with the United States (see Figures 3 and 4);16 (2) Geopolitically, the U.S maximum pressure policy poses a massive challenge to the EU’s policy of cooperation and rapprochement. However, given the EU’s stated objective of stability in West Asia, it is actually in its interest to be more critical of Iranian regional behavior. Indeed, its warmer relationship with Tehran has undermined its ability to effectively help reduce the Iranian–Saudi regional rivalry, which heavily weighs on many theaters of conflict throughout the region, including Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, Bahrain, and Yemen.17 (3) The EU–U.S. rift over Iran cannot be reduced to President Trump only, for concerns over Iranian behavior are likely to continue beyond the current U.S. administration, given the continuity of Tehran’s regional policies.18 Even if Trump leaves the scene, the EU will have to deal with multiple issues of concern raised by its allies and partners who will lobby for a more decisive approach than the one traditionally favored by Europe. It is for this reason that the call had been made early on to embed the JCPOA in a larger Western regional policy.19 It is therefore in the EU’s economic and geopolitical interest to cultivate a transatlantic common ground regarding Iran and the region.

Figure 3: European Exports to the United States

Figure 4: Iranian-European Imports and Exports

Economic Europe trumps political Europe

Brussels has explicitly encouraged European firms to continue and even deepen business ties with Iran, identifying nine areas for the normalization of trade and economic relations with Iran.20 In this vein, the European Commission updated the Blocking Statute to protect European companies’ Iran trade from re-instated U.S. extraterritorial sanctions. It also updated the European Investment Bank’s (EIB) external lending mandate by making Iran eligible for investment activities, although this remains a complicated endeavor.21 However, European politicians do not possess the power to force European economic actors to engage in commercial activities with Iran given the shadow of U.S. sanctions. Based on a cost-benefit calculation, many European firms have already halted their Iran activities out of concern over U.S. penalties, be they financial or exclusion from the far more important U.S. market.

Yet, one must differentiate between European multinational corporations (MNCs) and small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). MNCs’ exposure to the United States has already forced them to halt their Iran operations, thus abandoning their plans for expansion.22 SMEs, however, could indeed continue their business. In the case of Iran’s most important European economic partner Germany, where 5,000 to 7,000 companies regularly do business with Iran, German–Iranian trade was sustained by SMEs. Even during the height of the U.N., U.S., and EU sanctions on Iran between 2012 and 2015, Germany exported goods and services worth around 2 billion euros annually.23

For European economic engagement to continue with Iran, the EU must establish payment channels insulated from the U.S.-dominated financial circuit, with local banks playing an important role but necessitating a larger European commercial bank to conduct such payments.24For the time being, European companies have kept a minimum presence in Iran, thus adopting a wait-and-see approach until the picture between Washington and Tehran clears up.

A modified EU-Iran policy of cooperation and rapprochement

It is necessary to critically review the EU’s Iran policy before embarking on ways to modify it. For any transatlantic dialogue over Iran policy to succeed, it is indispensable to understand the genealogy leading to the May 2018 showdown. The U.S.–EU divide is the culmination of different perceptions of Iranian policies that preceded the U.S. withdrawal from JCPOA. While the European tendency has been to glorify Iran, the U.S. under Trump, has fallen back into demonizing it, as was the case during the George W. Bush administration.

The JCPOA: Successes and limitations

The JCPOA was hailed by the EU as its chief diplomatic success of the recent past, a signature achievement for resolving proliferation crises and promoting a rules-based global order. 25 After an intense two-year negotiation period, the JCPOA succeeded in bringing the decade-long controversy over Iran’s nuclear program to a halt. In accepting the deal in 2015, Iran agreed to extensively curb its nuclear program and subject it to a stringent inspection regime. In return, the five permanent members of the U.N. Security Council– plus Germany (the so-called P5+1), or the EU/E3+3 lifted nuclear-related economic sanctions upon the JCPOA’s implementation in 2016.

Critics have highlighted important flaws in the JCPOA. On one hand, these concern the sunset clauses: In 2020, the U.N. ban on Iranian arms imports and exports will be lifted. In 2023, the U.N. ban on assistance to Tehran’s ballistic missile program will expire, while Iran would be able to restart manufacturing advanced centrifuges. In 2026, most restrictions on the nuclear program will end, and five years later, all of them will be lifted. At each of these stages, given the ongoing U.S.–Iran conflict of which the nuclear crisis was merely a symptom, an international Iran crisis could be triggered anew. On the other, critics deplored the fact that issues pertaining to Iran’s foreign policy, most notably its ballistic missile program and its regional interventions, had been sidelined from the negotiations. Despite the political difficulties to successfully address many of those issues during the talks, their omission has borne the potential for future conflict, jeopardizing the viability of the agreement. The opportunity was missed to effectively use the JCPOA as the start of a process to address larger issues of concern in Iranian–Western relations, rather than as an end-game in itself, as the EU has preferred to view it.26A de facto authoritarian stability policy

The JCPOA enabled the EU to revitalize its relations with Iran. The idea was that trade and political rapprochement would be beneficial to both sides and implicitly contribute to an opening in the Islamic Republic. On July 14, 2015, the ink on the JCPOA had barely dried when Germany’s then-minister of economy and energy, Sigmar Gabriel, landed in Iran along with a large business delegation. The Germans were the first European government to make such a public overture. After all, some financial service firms hailed Iran as the most lucrative economic bonanza since the collapse of the Soviet Union.27 In Germany in particular, and in Europe in general, the renewal of economic and political ties with Iran has been rationalized in the public policy sphere as part of a policy of change through trade and rapprochement (CTTR),28 and as such has became almost immune to objective appraisal. While the German vice chancellor’s visit could be perceived and criticized as a premature overture to an unaltered authoritarian regime, Germany’s political and economic elite supported the visit. Similar situations occurred in France and the UK, albeit to a slightly lesser degree.29

CTTR policy is meant to facilitate a change within autocracies by engaging and trading with them. This strategy has often been invoked in the EU’s relations with autocratic regimes. At least in the public policy sphere, Europe expected that the JCPOA deal would have a positive effect on Iran’s domestic and foreign policies. However, a sober assessment reveals that a change has not materialized on any front.30

On the domestic front, expectations included more space for civil society and improvement of the human rights situation. JCPOA economic dividends were expected to benefit Iranians at large, to empower the reform-minded middle class, and ultimately to cultivate a gradual process of democratization. However, these expectations have not been met. In the domain of human rights, the situation has actually deteriorated, and President Hassan Rouhani’s rhetoric has dampened real reforms while his own Ministry of Intelligence became increasingly complicit in human rights violations.31 Iran under Rouhani has led the world in executions per capita.32 Space for activism has also remained highly restricted.33 It is no coincidence that Iran is currently one of the largest sources of refugees fleeing to major European countries. Furthermore, the EU’s foreign cultural and educational policies have not done enough to incorporate the diversity of Iranian society.34

On the economic front, after signing the JCPOA, the bulk of trade agreements with Iran benefited the economic empires of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), the Supreme Leader, and the bonyads (i.e. tax-exempt conglomerates that Iranian law treats as Islamic charities). In fact, by January 2017, out of almost 110 agreements signed after the JCPOA worth at least $80 billion, 90 were signed with companies owned or controlled by those Iranian state or semi-state entities.35 In other words, the revitalization of trade has almost exclusively benefited the authoritarian state. This is hardly surprising given the reality of the Islamic Republic’s politico-economic power configuration, in which a real private sector and free entrepreneurship barely exist in the face of dominant state or semi-state entities.

On the regional geopolitics front, according to the JCPOA’s preface, “[The EU+3] anticipate that full implementation of this JCPOA will positively contribute to regional and international peace and security.”36 For others, including many of Iran’s neighbors, the expectation was that Iran’s constructive engagement with the West would translate into the moderation of its regional policies. In reality, President Rouhani’s policy of moderation toward the West and on the nuclear issue has been effectively undercut by an increasingly assertive and expansive Iranian regional policy run by the IRGC and the Supreme Leader’s Office.37

Expectations of moderation in Iran’s domestic politics and regional policy have not been realized. Internally, the human rights situation and socioeconomic conditions have worsened.38 Economically, the Islamic Republic’s elites benefited from the process, while most Iranians did not. Disillusionment spread among Iranians, ultimately paving the way to the 2017-2018 revolt. Externally, Iran has pursued its goal of retaining and expanding its regional power with more intransigence. This policy, in turn, has fueled the conflicts in Iraq and Syria and helped escalate tensions with Saudi Arabia and Israel, two important EU partners. The balancing act between maintaining the EU’s close relationships with these partners and simultaneous rapprochement with Iran has constituted a tension that risks turning into open confrontation, putting the EU in a difficult position.

In conclusion, trade and rapprochement toward Iran have not set the stage for change. In fact, the EU’s Iran policy has had more similarities with a policy of authoritarian stability, similar to those pursued over the last decades with other autocracies in the Middle East and North Africa region. This finding was confirmed by an Iran specialist at the German Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy and a senior member of the EU’s Iran Task Force, both of whom confided this view to the author in June 2017 and February 2018 respectively, while their institutions’ public stances claimed the contrary.

Revisiting the shortcomings of the EU’s Iran policy

The shortcomings of the EU’s Iran policy stem from a tendency to glorify in its account of Iranian politics and policies.39 Over the past decades, European states have tended to exaggerate factional differences between the Iranian regime’s hardliners and moderates. Moreover, in the wake of the JCPOA, Europe’s position toward Tehran has been concerned that a more robust approach would imperil its economic and geostrategic interests in its process of rapprochement. Concerning the geopolitics of the region, Europe has succumbed to the fallacy of extrapolation by assuming that the constructive engagement policy, which led to the JCPOA, would translate into similar changes in Iran’s regional policies. Europe’s stance on regional geopolitics was underpinned by stability concerns. In Syria in particular, its interests de-facto aligned with those of the Islamic Republic, allowing the survival of President Bashar Assad’s regime in Syria. As such, Europe by and large ignored that the Assad regime’s barbarity was reinforcing jihadi terrorism, the fight against which the EU has prioritized.40

Europe needs to consider that Iran cannot be viewed as a factor of stability in West Asia. While the EU has rightly increased its awareness regarding malign activities by Saudi Arabia and its allies, it has neglected clear risks regarding Iran, particularly its regional expansionism and the promotion of parallel state structures,41 which have contributed to a marked deterioration in Iran’s relations with its neighbors. In Iraq and Syria, Tehran has been viewed as overplaying its hand. As such, these Iranian policies run counter to the EU’s goal of promoting long-term stability in the region and strengthening state structures there.

Iran’s triple crisis and its ramifications

The 2017-2018 revolt against the regime has ushered in a new chapter in the history of the Islamic Republic.42 In its relations with Tehran, Europe must draw important conclusions from this landmark development. A triple crisis is plaguing the Islamic Republic, covering socioeconomic, political, and environmental dimensions – all of which have acted as interrelated drivers for continuous protests since the 2017-2018 revolt. Firstly, Iran suffers from socioeconomic misery, with half the population living close to the poverty line, almost one third of the urban population living in slums, and one of the world’s highest rates of youth unemployment. The lack of socioeconomic mobility is a product of a political economy favoring regime members and loyalists. In addition, social frustration set in over the lack of a trickling-down effect from JCPOA GDP growth. The economic situation is further exacerbated by the absence of much needed structural reforms.43 Furthermore, the Iranian economy suffers from mismanagement, cronyism, and corruption. Although U.S. sanctions have contributed to the deteriorating situation in the country, with rising prices and a plummeting national currency, their overall impact on Iran’s self-inflicted economic situation has often been overstated.44 Secondly, the Islamic Republic faces an unprecedented political stalemate. As can be witnessed from various protest slogans, hardline and moderate factions, as well as the clerical establishment (many of whom are reformists), all have been the target of popular rage. As a result, the entire regime’s legitimacy has been virulently questioned.45 Thirdly, Iran suffers from an environmental catastrophe that is largely home-made. According to Iranian and U.N. authorities, if ongoing trends prevail, half of the country’s provinces will be inhabitable in 15–20 years, and by 2050 the country could turn into a desert. The environmental disaster, including water scarcity, is arguably a national security threat. It has already started to threaten the livelihood of tens of millions of Iranians.46 Protests fueled by these developments have often been met with repression.

The severity of this new phase is characterized by a number of partly novel factors: (1) Protest slogans exhibit an unprecedented level of politicization that are targeting all factions of the regime; they are not sparing the moderates, as was the case during the 2009 Green Movement; (2) An irreversible chasm is emerging between the state and society, which can only be addressed by political and economic structural reforms; (3) In contrast to the Green Movement, whose social base was largely the urban middle class seeking greater political participation, the social base of the 2017-2018 revolt has been the lower socioeconomic strata, conventionally conceived of as the regime’s social base; (4) The loss of legitimacy of moderate élite groups, including Rouhani and the reformists, ushered in a deep crisis of factional rule in the Islamic Republic;47 and (5) An acknowledgment by Iran’s security establishment that the main threat to national security is from inside and not outside the country.48

Importantly, this triple crisis is set to continue, as its underlying causes are likely to remain unaltered or worsen. This new era in the history of the Islamic Republic of Iran is marked by turmoil and potential instability. Another illustration of the regime’s crisis is that U.S. pressure has failed to create a rally ‘round the flag effect among Iranians. Protests with anti-regime slogans continue, blaming the deteriorating political and economic situation on the regime rather than on U.S. policy or sanctions.49 More than anything else, and due to the lack of alternatives, this crisis has the potential to pave the way for Iranian negotiations with the United States while increasing Tehran’s dependency vis-à-vis great-powers, including Russia and Europe.

Policy recommendations

A modified European Iran policy would live up to the EU’s foreign policy concept of principled pragmatism, which aims to combine “a realistic assessment of the current strategic environment” with “an idealistic aspiration to advance a better world,” as enshrined in its Global Strategy.50 Europe must chart a more balanced Iran strategy of maintaining economic and political ties with Iran without falling into the trap of promoting an uncritical authoritarian stability policy. More of the same is unlikely to avoid chaos and instability.51 Europe must look beyond safeguarding the JCPOA, or as one German policymaker put it, its “nuclear hypnosis,”52 and move toward a more balanced approach of continued cooperation while encouraging Iranian course corrections.

As an indispensable starting point, Europe must first establish a unified Iran policy that is binding to all member states to avoid opportunistic behavior by single countries. Also, it is essential to find a common ground among slightly differing European positions.53 A readjusted policy should include the following core policy elements:

Keep the JCPOA alive

With the support of Russia and China, the EU should save the JCPOA for two reasons: (1) containing the Iran nuclear program would help prevent a nuclear arms race in the Middle East; (2) maintaining the JCPOA ensures that the EU will retain leverage over Iran, which would otherwise dissipate if the deal completely falls apart. To ensure the survival of the JCPOA, Europe must maintain commercial interactions with Iran through its SMEs, allow Iran to export its oil to Europe, and enable European financial institutions to process payments.

Engage Washington: A transatlantic Iran policy should not be buried

Despite alienation from the Trump administration, Europe needs to pursue steps toward finding a transatlantic common ground on Iran. The EU should engage with the State Department’s Iran Action Group. Also, it must continue to seek exemptions from U.S. sanctions.54 While not burning bridges with Washington, the EU can simultaneously pursue the project of strengthening its autonomy by creating payment channels independent from the United States, such as a European monetary fund and an independent SWIFT system.55 However, these goals cannot be attained in the short-term.56Use the EU’s leverage with Iran, cognizant of its comparative advantages

The EU should utilize its amassed weight in Tehran toward extracting gradual change in its domestic and regional behavior, while highlighting the benefits of such changes to Iran. Cognizant of the comparative advantages it has in Tehran, the EU should not shy away from introducing conditions for cooperation. Taking a steadfast approach, the EU will present an important driver for Tehran to start changing its behavior. Despite Tehran’s official refusal to engage with Brussels over domestic issues and its regional role, a genuine concern over domestic economic instability will encourage it to accept the EU’s promotion of gradual changes. While maintaining dialogue with Iran on regional security, Europe should adopt a dual strategy: (1) guarding Iran against the demonization of its role and (2) asking Iran for constraints in that role. Europe should differentiate between what Iran views as a deterrence strategy against what many of its neighbors regard as hegemonic ambitions.57Avoid pro-regime favoritism

Europe should not re-create the impression it gave during the 2017-2018 revolt, that it favors the regime over society. The EU should avoid alienating large sections of Iranian society, thereby ensuring its long-term reputation and interests in the country. With the prospect of deteriorating domestic conditions in Iran, Europe needs to be prepared for how to react if events in Iran escalate. If they do, the EU needs to take a clear stance in line with its own values and in support of the Iranian people’s democratic rights. Failing to do so will make it easier for the regime to engage in suppression and increase the prospect of a bloodbath. Leaving the scene to the United States would play into the hands of the regime’s repressive apparatuses. The EU must use its relations with various sections of Iran’s elite, signaling to them that state repression will negatively impact its economic and political engagement and support. Europe’s largely favorable reactions toward the 2010-2011 Arab Spring can serve as an example.

Initiate an overdue paradigm shift: Harmonizing foreign and development policies for the sake of sustainable stability

The authoritarian stability and neoliberal economic policies of the past have failed to produce stability in Europe’s neighborhood, including Iran. The EU must now prepare the conceptual grounds for a paradigm shift in its foreign policy. It must support good governance and inclusive economic growth. Toward that end, the lessons from the Arab Spring, as formulated by the German Development Institute (DIE),58 ought to be taken into consideration. Only through harmonizing foreign and development policies in the Middle East can the EU promote long-term stability in Europe’s troubled neighborhood. To devise the actual policies for this paradigm shift, the EU needs to establish an independent expert committee that is not confined by political and bureaucratic constraints and considerations.59

-

Footnotes

- Donald J. Trump, “Ceasing U.S. Participation in the JCPOA and Taking Additional Action to Counter Iran’s Malign Influence and Deny Iran All Paths to a Nuclear Weapon,” Presidential Memorandum, May 8, 2018, https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/ceasing-u-s-participation-jcpoa-taking-additional-action-counter-irans-malign-influence-deny-iran-paths-nuclear-weapon/; Mike Pompeo, “After the Deal: A New Iran Strategy,” Heritage Foundation, May 21, 2018, https://www.state.gov/secretary/remarks/2018/05/282301.htm.

- Jonathan Landay, Arshad Mohammed, Warren Strobel, and John Walcott, “U.S. launches campaign to erode support for Iran’s leaders,” Reuters, July 21, 2018, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-iran/u-s-launches-campaign-to-erode-support-for-irans-leaders-idUSKBN1KB0UR.

- See even the denial by the administration official with the most hawkish, “regime change” past on Iran, National Security Advisor John Bolton: “John Bolton: North Korea has not ‘taken effective steps’ to denuclearize,” interviewed by Nick Schifrin, PBS NewsHour, August 6, 2018, https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/john-bolton-north-korea-has-not-taken-effective-steps-to-denuclearize.

- “Trump says Iran will seek fresh deal as looming sanctions weigh on economy,” Reuters, July 12, 2018, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-nato-summit-iran/trump-says-iran-will-seek-fresh-deal-as-looming-sanctions-weigh-on-economy-idUSKBN1K21LY; Jeremy Diamond and Nicole Gaouette, “Trump says he’d meet with Iran without preconditions’ ‘whenever they want’,” CNN, July 31, 2018, https://edition.cnn.com/2018/07/30/politics/trump-iran-talks-without-preconditions/index.html.

- Parisa Hafezi, “Iran’s Khamenei rejects Trump offer of talks, chides government over economy,” Reuters, August 13, 2018, https://uk.reuters.com/article/uk-iran-usa/irans-khamenei-rejects-trump-offer-of-talks-chides-government-over-economy-idUKKBN1KY14B.

- Suzanne Maloney, “Trump wants a bigger, better deal with Iran. What does Tehran want?,” Order from Chaos(blog), Brookings Institution, August 8, 2018, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2018/08/08/trump-wants-a-bigger-better-deal-with-iran-what-does-tehran-want/; Vali Nasr, “What It Would Take for Iran to Talk to Trump,” The Atlantic, August 8, 2018, https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2018/08/iran-talks-trump-preconditions-nuclear-deal-obama-north-korea/567077/.

- There are indications that Oman has already been the site for exchanges between Tehran and Washington. See Rainer Hermann and Majid Sattar, “Trump geht auf Iran zu: Wieder ein großer Deal?” [Trump approches Iran: Again a grand deal?], Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, July 31, 2018, http://www.faz.net/aktuell/politik/trumps-praesidentschaft/trump-geht-auf-iran-und-rohani-zu-wieder-ein-grosser-deal-15716824.html.

- United Nations Security Council, “Resolution 2231,” July 20, 2015, https://undocs.org/S/RES/2231(2015).

- Amir Ahmadi Arian and Rahman Bouzari, “What Sanctions Mean to Iranians,” New York Times, May 10, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/05/10/opinion/sanctions-iran-nuclear-deal-protests.html; Karim Sadjadpour, “How Trump Could Revive the Iranian Regime,” The Atlantic, May 29, 2018, https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2018/05/iran-trump-khamenei-obama-pompeo/561449/; Michael McFaul and Mohsen Milani, “Why Trump’s plans for regime change in Iran will have the opposite effect,” Washington Post, May 30, 2018, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/global-opinions/wp/2018/05/30/why-trumps-plans-for-regime-change-in-iran-will-have-the-opposite-effect/; Ali Fathollah-Nejad, “The End of the Iran Deal Spells the End of Iranian Moderates,” The National Interest, June 26, 2018, http://nationalinterest.org/feature/the-end-the-iran-deal-spells-the-end-iranian-moderates-26418.

- Suzanne Maloney, “The Trump administration’s Plan B on Iran is no plan at all,” Order from Chaos(blog), Brookings Institution, May 22, 2018, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2018/05/22/the-trump-administrations-plan-b-on-iran-is-no-plan-at-all/; Payam Mohseni, “Closing the deal: The US, Iran, and the JCPOA,” Al Jazeera English, May 13, 2018, https://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/closing-deal-iran-jcpoa-180512115208725.html.

- European Union Global Strategy, “Shared Vision, Common Action: A Stronger Europe, A Global Strategy for the European Union’s Foreign And Security Policy,” June 2016, 35, http://eeas.europa.eu/archives/docs/top_stories/pdf/eugs_review_web.pdf.

- Ali Fathollah-Nejad, “Germany’s Relations with Iran beyond the Nuclear Deal: Readjusting Foreign and Development Policy” in Foreign Policy and the Next German Government: Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats, eds. Christian Mölling and Daniela Schwarzer (DGAPkompakt, No. 7, Summer 2017), 27–30, https://dgap.org/sites/default/files/article_downloads/12_fathollah-nejad_iran.pdf.

- See Joost Hiltermann, “Europe’s dilemma after US withdrawal from Iran nuclear deal,” video interview, International Politics and Society: Friedrich Ebert Foundation (FES), July 23, 2018, https://www.ips-journal.eu/videos/show/article/show/europes-dilemma-after-us-withdrawal-from-iran-nuclear-deal-2874/. In this vein, Russia’s alleged readiness to invest $50 billion in Iran’s oil and gas sectors can be questioned. Rather Russia is using Iran’s current international weakness to further its own interests, as Moscow’s suggestion for an oil-for-goods program might signal. See Henry Foy and Najmeh Bozorgmehr, “Russia ready to invest $50bn in Iran’s energy industry,” Financial Times, July 13, 2018, https://www.ft.com/content/db4c44c8-869b-11e8-96dd-fa565ec55929.

- “To remain in JCPOA, Imam Khamenei announces conditions to be met by Europe,” Khamenei.ir, May 23, 2018, http://english.khamenei.ir/news/5696/To-remain-in-JCPOA-Imam-Khamenei-announces-conditions-to-be; see “Ayatollah Khamenei Outlines Tehran’s Conditions for Staying in Iran Nuclear Deal,” Tasnim News Agency, May 24, 2018, https://www.tasnimnews.com/en/news/2018/05/24/1732859/ayatollah-khamenei-outlines-tehran-s-conditions-for-staying-in-iran-nuclear-deal; see also Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Islamic Republic, “Statement of the Government of the Islamic Republic of Iran on U.S. Government Withdrawal from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action,” May 10, 2018, http://en.mfa.ir/index.aspx?siteid=3&fkeyid=&siteid=3&pageid=36409&newsview=514000.

- Djavad Salehi-Isfahani, “How Iran Will Respond to New Sanctions,” Project Syndicate, May 2, 2018, https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/iran-sanctions-nuclear-deal-by-djavad-salehi-isfahani-2018-05.

- In the case of Iran’s most important European partner, Germany, German trade with the United States is about $170 billion, in contrast with German trade with Iran, worth around $3 billion. Federal Statistical Office (Destatis), “Außenhandel: Rangfolge der Handelspartner im Außenhandel der Bundesrepublik – 2017” [Foreign trade: Ranking of the trading partners in Federal Republic’s foreign trade–2017], accessed September 23, 2018, https://www.destatis.de/DE/ZahlenFakten/GesamtwirtschaftUmwelt/Aussenhandel/Tabellen/RangfolgeHandelspartner.pdf.

- For details on the rivalry’s sources and drivers, see Ali Fathollah-Nejad “The Iranian–Saudi Hegemonic Rivalry,” Iran Matters(blog), Belfer Center’s Iran Project, Harvard University, October 25, 2017, https://www.belfercenter.org/publication/iranian-saudi-hegemonic-rivalry.

- For the latter, see Mahmood Sariolghalam, “Prospects for Change in Iranian Foreign Policy,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, February 20, 2018, http://carnegieendowment.org/2018/02/20/prospects-for-change-in-iranian-foreign-policy-pub-75569.

- See Robert Einhorn, “The JCPOA should be maintained and reinforced with a broad regional strategy,” Brookings Institution, September 29, 2016, https://www.brookings.edu/research/the-jcpoa-should-be-maintained-and-reinforced-with-a-broad-regional-strategy/.

- European Union External Action, “Remarks by HR/VP Mogherini at the press conference following ministerial meetings of the EU/E3 and EU/E3 and Iran,” May 15, 2018, https://eeas.europa.eu/headquarters/headquarters-homepage/44599/remarks-hrvp-mogherini-press-conference-following-ministerial-meetings-eue3-and-eue3-and-iran_en.

- European Commission, “Upholding the EU’s commitment to the Iran nuclear deal and protecting the interests of European companies, Next Steps,” Daily News, June 6, 2018, http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_MEX-18-4085_en.htm; William Horobin and Birgit Jennen, “EU Looking to Sidestep U.S. Sanctions With Payments System Plan,” Bloomberg, August 27, 2018, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-08-27/eu-looking-to-sidestep-u-s-sanctions-with-payments-system-plan.

- See the cases of German MNCs Deutsche Telekom, Daimler, Deutsche Bahn, and Herrenknecht (manufacturer of tunnel boring machines): Elisabeth Behrmann and Chris Reiter, “Daimler Shelves Iran Expansion Plan on U.S. Trade Sanctions,” Bloomberg, August 7, 2018, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-08-07/daimler-scraps-iran-expansion-plan-because-of-u-s-sanctions-jkjijlfl; Christian Schlesiger, “ Herrenknecht zieht sich aus Iran zurück” [Herrenknecht retreats from Iran], WirtschaftsWoche, August 9, 2018, https://www.wiwo.de/unternehmen/industrie/folge-der-us-sanktionen-herrenknecht-zieht-sich-aus-iran-zurueck/22895446.html; “Telekom und die Deutsche Bahn ziehen sich aus dem Iran zurück” Telekom and Deutsche Bahn retreat from Iran, Handelsblatt, August 16, 2018, https://www.handelsblatt.com/unternehmen/dienstleister/us-sanktionen-telekom-und-die-deutsche-bahn-ziehen-sich-aus-dem-iran-zurueck/22919060.html.

- Michael Tockuss, Managing Board member, German Iranian Chamber of Commerce Association, interviewed by Christoph Heinemann, Deutschlandfunk, August 7, 2018, https://www.deutschlandfunk.de/deutsch-iranische-wirtschaftsbeziehungen-wir-erwarten.694.de.html?dram:article_id=424882.

- See the statements by Dagmar von Bohnstein, delegate of the German economy in Iran based at the German–Iranian Chamber of Industry and Commerce in Tehran, in Karin Senz, “Iran-Geschäfte deutscher Firmen: Rückzug statt Goldgräberstimmung” [Iran business of German companies: Retreat instead of gold-rush mood], tagesschau.de, August 14, 2018, http://www.tagesschau.de/ausland/iran-sanktionen-129.html.

- European Union Global Strategy, “Shared Vision, Common Action,” 15, 42.

- See Ali Ansari, “What future for the Iran nuclear deal?,” Prospect, May 5, 2018, https://www.prospectmagazine.co.uk/world/what-future-for-the-iran-nuclear-deal.

- See the late 2015 statement by Morgan Stanley: “Iran is the largest economy to return to the global fold since the break-up of the Soviet Union and similarities include the complexity of the sanctions regime involved, the attempt at political rapprochement with the West and Iran’s vast energy wealth. […] In many respects, there is no direct comparator for Iran, given its economic size, the scale of the sanctions imposed and its political structure. In particular, the potential reintegration of Iran into the global economy is arguably uncharted territory in that there is no other hydrocarbon frontier economy that has been subjected to comparable economic and political sanctions.” Mike Bird, “Morgan Stanley: Iran Is the Biggest Thing for the Global Economy since the Berlin Wall Fell,” Business Insider, December 2, 2015, http://uk.businessinsider.com/morgan-stanley-iran-is-the-biggest-thing-for-the-global-economy-since-the-berlin-wall-fell-2015-12.

- See Anne Bartels et al., “Change through Trade: Fair and Sustainable Trade Policy for the 21st Century, European Parliamentary Group Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats (S&D),” accessed September 23, 2018, http://www.bernd-lange.de/imperia/md/content/bezirkhannover/berndlange/2016/bl_bro_handelsbeziehungen_en_rz_web.pdf. The CTTR approach originated in the context of then-German Chancellor Willy Brandt’s policy toward the Eastern Bloc, famously dubbed Ostpolitik.

- For the French context, see the explanations by Clément Therme in Marie-France Chatin, “Iran : les défis du retour” [Iran: the challenges of return], Radio France Internationale (RFI), November 19, 2016, http://www.rfi.fr/emission/20161119-iran-sanctions-etats-unis-trump-election-obama.

- Ali Fathollah Nejad, “The West’s Iran Policy: For Real Change Through Trade,” Qantara.de: Dialogue with the Islamic World, August 23, 2017, http://en.qantara.de/node/28703.

- Center for Human Rights in Iran (CHRI), “Rouhani’s Citizens’ Rights Charter: A Harmful Distraction,” May 2018, https://www.iranhumanrights.org/2018/05/rouhanis-citizens-rights-charter-a-harmful-distraction/. See also CHRI, “Rouhani’s Intelligence Ministry and Khamenei’s IRGC Widen Crackdown Ahead of Election,” March 16, 2017; Raha Bahreini, “Iran just gave foreign delegates a tour around a ‘luxury’ part of one of their most notorious prisons,” Independent, July 13, 2017, https://www.independent.co.uk/voices/iranian-evin-prison-iran-luxury-foreign-delegates-tour-prisoners-inhumane-conditions-torture-human-a7838786.html ; CHRI, “Rouhani Should Be Called to Account for Human Rights Abuses in Iran at UN Gathering,” September 19, 2018, https://www.iranhumanrights.org/2018/09/rouhani-should-be-called-to-account-for-human-rights-abuses-in-iran-at-un-gathering/.

- George Arnett, “Executions in Saudi Arabia and Iran – the Numbers,” The Guardian, January 4, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/news/datablog/2016/jan/04/executions-in-saudi-arabia-iran-numbers-china.

- Human rights activists, dissidents, women’s rights activists, labor activists, and minorities suffer ongoing political repression. For instance, in late August 2017, Tehran-based human-rights lawyer Nasrin Sotoudeh, recipient of the 2012 European Parliament’s Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought, together with director Jafar Panahi, said: “No, with President Rouhani the human rights situation hasn’t improved. In the last four years, we’ve experienced more arbitrariness than ever. The repression of human rights activists, dissidents, women rights activists, trade unionists, and minorities is part of everyday life. The security forces have intruded all parts of our life.” Cited in Shabnam von Hein, “Rohanis Wähler(innen) enttäuscht” [Rouhani’s voters disappointed], Deutsche Welle (DW), August 23, 2017, https://www.dw.com/de/rohanis-w%C3%A4hlerinnen-entt%C3%A4uscht/a-40208389. On Rouhani’s broken promise of extending press freedom, see Committee to Protect Journalists(CPJ), “On the Table: Why now is the time to sway Rouhani to meet his promises for press freedom in Iran,” May 24, 2018, https://cpj.org/reports/2018/05/on-the-table-rouhani-iran-press-freedom-journalists-deal-EU-US.php.

- For instance, German cultural, journalistic, and academic exchanges with Iran have overwhelmingly sidelined dissident voices, an integral part of Iranian political culture. Rather, these exchanges have often merely followed the paths offered by the Islamic Republic, prompting criticism by independent Iranian artists. See Ali Fathollah-Nejad interviewed by Dorothea Grassmann (Institute for International Cultural Relations-IFA),“Cultural Rapprochement with Iran: Laden with Promise,” Qantara.de: Dialogue with the Islamic World, April 4, 2016, http://en.qantara.de/node/23316. For policy recommendations, see Ali Fathollah-Nejad, “Cultural and academic relations between Iran and the West after the nuclear deal: Policy recommendations,” Brookings Institution, November 15, 2017, https://www.brookings.edu/research/cultural-and-academic-relations-between-iran-and-the-west-after-the-nuclear-deal-policy-recommendations/. The author has been writing the major study on the future of German–Iranian cultural and academic relations after the nuclear deal, as commissioned by IFA.

- Yeganeh Torbati, Bozorgmehr Sharafedin, and Babak Dehghanpisheh, “After Iran’s Nuclear Pact, State Firms Win Most Foreign Deals,” Reuters, January 19, 2017, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-iran-contracts-insight/after-irans-nuclear-pact-state-firms-win-most-foreign-deals-idUSKBN15328S.

- European Union External Action, “Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action,” July 14, 2015, https://eeas.europa.eu/headquarters/headquarters-homepage/8710/joint-comprehensive-plan-action_en.

- Ali Fathollah-Nejad, “German–Iranian Relations after the Nuclear Deal: Geopolitical and Economic Dimensions,” Insight Turkey, Vol. 18, No. 1 (Winter 2016), 59–75 and 64–67, http://www.insightturkey.com/fathollah/germaniranian-relations-after-the-nuclear-deal-geopolitical-and-economic-dimensions.

- In relation to Rouhani’s economic policy doctrine, see Ali Fathollah-Nejad, “Rouhani’s Neoliberal Doctrine Has Failed Iran,” Middle East Institute, May 18, 2017, http://www.mei.edu/content/article/rouhani-s-neoliberal-doctrine-has-failed-iran.

- [1] Ali Fathollah-Nejad, “Kritik der Iran-Analysen unter Präsident Rohani: Von Dämonisierung zu Glorifizierung” [Critique of Iran analyses under President Rouhani: From demonization to glorification], in Iran-Reader 2017: Beiträge zum deutsch-iranischen Kulturdialog, Sankt Augustin & Berlin, ed. Oliver Ernst (Germany: Konrad Adenauer Foundation (KAS), 2017), 9–24, http://www.kas.de/wf/de/33.49042/.

- For details, see Fathollah-Nejad, “German–Iranian Relations after the Nuclear Deal,” 64–67; “Iran and Syria’s War: Fighting ‘Terror’ Publicly, Mourning the Dead Secretly,” Al Jazeera English, May 1, 2018, https://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/iran-fighting-terror-publicly-mourning-dead-secretly-180430140249437.html.

- Suzanne Maloney, “The Roots and Evolution of Iran’s Regional Strategy,” Atlantic Council, Issue Brief, October 2, 2017, http://www.atlanticcouncil.org/publications/issue-briefs/the-roots-drivers-and-evolution-of-iran-s-regional-strategy; Ranj Alaaldin, “How Iran Used the Hezbollah Model to Dominate Iraq and Syria,” International New York Times, March 31, 2018, A9, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/03/30/opinion/iran-hezbollah-iraq-syria.html; Guido Steinberg, “Umgang mit dem Iran: Fünf Thesen auf dem Prüfstand,” [Dealing with Iran: Five theses under scrutiny], Internationale Politik, Berlin: German Council on Foreign Relations (DGAP), May/June 2018, 64–69, https://zeitschrift-ip.dgap.org/de/ip-die-zeitschrift/archiv/jahrgang-2018/mai-juni-2018/umgang-mit-dem-iran.

- On the revolt, see Ali Ansari, “As protests rage in Iran, there are few certainties—except that the Revolution has run out of steam,” Prospect, January 3, 2018, https://www.prospectmagazine.co.uk/politics/as-protests-rage-in-iran-there-are-few-certainties-except-that-the-revolution-has-run-out-of-steam; Hamid Dabashi, “Iran Protests,” seminar at the Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies (ACRPS), Doha, January 3, 2018, https://www.dohainstitute.org/en/Events/Pages/Protests_in_Iran.aspx; Hassan Hakimian, “What’s driving Iran’s protests?”, Project Syndicate, January 6, 2018, https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/iran-protests-economic-growth-unemployment-by-hassan-hakimian-2018-01; Ali Fathollah-Nejad, “Causes behind Iran’s Protests: A Preliminary Account,” Al Jazeera English, January 6, 2018, http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/iran-protests-preliminary-account-180105232533539.html; Nader Habibi, “Why Iran’s protests matter this time,” The Conversation, January 8, 2018, https://theconversation.com/why-irans-protests-matter-this-time-89745; Asef Bayat, The Fire That Fueled the Iran Protests, The Atlantic, January 27, 2018, https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2018/01/iran-protest-mashaad-green-class-labor-economy/551690/; Ali Fathollah-Nejad, “There’s more to Iran’s protests than you’ve been told,” PBS NewsHour, April 3, 2018, https://www.pbs.org/newshour/world/opinion-theres-more-to-irans-protests-than-youve-been-told; Siavash Saffari, “Iran Protests: Changing Dynamics between the Islamic Republic and the Poor,” DiverseAsia, Seoul National University Asia Center (SNUAC), No. 1 , June 2018, http://diverseasia.snu.ac.kr/?p=324.

- Fathollah-Nejad, “Rouhani’s Neoliberal Doctrine Has Failed Iran”; “Where will the Rouhani administration’s neoliberal doctrine lead Iran to?” (Persian), pecritique.com (Political Economy Critique), November/December 2017, pecritique.com/2017/11/20/آموزهی-نولیبرال-دولت-روحانی-ایران-ر/; Shahram Khosravi, “How the Other Half Lives in Iran,” International New York Times, January 15, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/01/14/opinion/iran-protests-inequality.html.

- For instance, according to Hossein Raghfar, an economist at Tehran’s Allameh Tabataba’i University, Iran’s economic problems can be attributed to only 15 percent to sanctions; cited in Natalie Amiri, “US-Sanktionen: Wirtschaftliche Lage im Iran wird schwieriger” [U.S. sanctions: Economic situation Iran gets more difficult], Tagesschau, August 6, 2018, http://www.tagesschau.de/multimedia/video/video-433791.html.

- Fathollah-Nejad, “There’s more to Iran’s protests than you’ve been told.”

- Small Media & Heinrich Böll Foundation, “Paradise Lost? Developing solutions to Iran’s environmental crisis,”2016, https://smallmedia.org.uk/work/paradise-lost-irans-environmental-crisis; Ali Fathollah-Nejad, “Wüste Eden: Über Irans Wasser- und Umweltkrisen” [Desert Eden: On Iran’s water and evironmental crises], ARTE-Magazin, May 2018, 21–22, https://www.arte.tv/sites/de/das-arte-magazin/2018/05/15/die-wueste-eden/; Ali Fathollah-Nejad, “Proteste im Iran: Politikum Umweltkrise” [Protests in Iran: Political issue environmental crisis], Heinrich Böll Foundation, July 6, 2018, https://www.boell.de/de/2018/07/06/proteste-im-iran-politikum-umweltkrise.

- In this vein, in the wake of the revolt in February 2018, Mohsen Rezaee, Secretary of the Expediency Council and former IRGC Commander, and as such one of the leading members of the country’s security establishment, said on state TV: “The truth is that the era of administering the country fractionally is over. The roots of the country’s problems can no longer be solved with the dichotomy of principlism–reformism. This game is over. If political actors haven’t realized that they cannot run the country with this game, one should say it is either because they are not paying attention, or they have realized it but are so much entangled in their own mental issues that they have lost their sense of responsibility.” “Time of principlism-reformism game is over!,” Iran Tag, February 19, 2018, http://irantag.net/?p=5145.

- See the statement by IRGC Major-General Yahya Rahim Safavi in Ahmad Majidyar, “Water crisis fueling tension between Iran and its neighbors,” Middle East Institute, February 28, 2018, http://www.mei.edu/content/article/io/water-crisis-fueling-tension-between-iran-and-its-neighbors.

- On the latter, see Rahman Bouzari [journalist with the pro-reform daily Shargh], “What do the Iranian people want? Faced with a false choice between authoritarianism and imperialism, the Iranian people reject both,” Al Jazeera English, June 4, 2018, https://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/iranian-people-nuclear-deal-180604101300453.html; Ali Ansari, “It’s not Trump Iranians are worried about – it’s their homegrown crises,” The Guardian, July 24, 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/jul/24/trump-iranians-crises-president-twitter-economic; Najmeh Bozorgmehr and Monavar Khalaj, “Poor Iranians bear the brunt of sanctions as food prices soar,” Financial Times, August 7, 2018, https://www.ft.com/content/d0e17cac-94dc-11e8-b747-fb1e803ee64e; Saeed Kamali Dehghan, “‘Desperate to find a way out’: Iran edges towards precipice,” The Guardian, July 20, 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/jul/20/desperate-to-find-a-way-out-iran-edges-towards-precipice.

- European Union Global Strategy, “Shared Vision, Common Action,” 8.

- For German concerns over such a scenario, “Maas warnt vor Chaos in Iran” [Maas warns of chaos in Iran], Spiegel Online, August 8, 2018, http://www.spiegel.de/politik/ausland/us-sanktionen-heiko-maas-warnt-vor-chaos-in-iran-a-1222133.html; Christiane Hoffmann, “What if Iran becomes the next Syria?”, Der Spiegel, editorial, No. 33/2018, August 14, 2018, http://www.spiegel.de/international/world/editorial-what-if-iran-becomes-the-next-syria-a-1223167.html.

- “US-Sanktionen gegen den Iran – “Die Zivilbevölkerung wird davon massiv betroffen sein” [U.S. sanctions against Iran – “Civil society will be massively affected”], Omid Nouripour, the German Green Party’s foreign-policy spokesperson and his party’s chairman in the Bundestag’s Committee on Foreign Affairs, interviewed by Dirk-Oliver Heckmann, Deutschlandfunk, August 6, 2018, https://www.deutschlandfunk.de/us-sanktionen-gegen-den-iran-die-zivilbevoelkerung-wird.694.de.html?dram:article_id=424745.

- See Piotr Buras & Anthony Dworkin & Silvia Francescon & Josef Janning & Manuel Lafont Rapnouil & Jeremy Shapiro, “The View from the Capitals: Trump’s withdrawal from the Iran deal,” European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR), May 11, 2018, http://www.ecfr.eu/publications/summary/vfc_the_view_from_the_capitals_trumps_withdrawal_from_the_iran_deal.

- See also the letter by the E3 to U.S. authorities, asking them exempt European companies’ Iran business from U.S. sanctions; Bruno Le Maire, Twitter post, June 8, 2018, https://twitter.com/BrunoLeMaire/status/1004246658010542080.

- See the statement by the Directors of IFRI(Institut français des relations internationals), Chatham House – The Royal Institute of International Affairs, German Council on Foreign Relations (DGAP), Istituto Affari Internazionali (IAI) respectively, Thomas Gonnart, Robin Niblett, Daniela Schwarzer, and Nathalie Tocci, “America is more than Trump: Europe Should Defend the Iran Deal Without Burning Bridges to the US,” IFRI, May 18, 2018, http://www.iai.it/en/pubblicazioni/europe-trump-and-iran-nuclear-deal; Heiko Maas (German Foreign Minister), “Balancierte Partnerschaft zwischen Europa und den USA: Wir lassen nicht zu, dass die USA über unsere Köpfe hinweg handeln” [Balanced partnership between Europe and the U.S.: We don’t allow the U.S. to go over our head], Handelsblatt, August 21, 2018, https://www.handelsblatt.com/meinung/gastbeitraege/gastkommentar-wir-lassen-nicht-zu-dass-die-usa-ueber-unsere-koepfe-hinweg-handeln/22933006.html.

- See “USA: So reagierten Experten auf Maas’ US-Strategie” [USA: This is how experts reacted to Maas’ U.S. strategy] Handelsblatt, August 22, 2018, https://www.handelsblatt.com/politik/international/reaktionen-auf-vorschlag-des-aussenministers-hoechste-zeit-den-ernst-der-lage-zu-begreifen-experten-loben-maas-usa-strategie/22938206.html

- See Emile Hokayem, “Saudi Arabia Has No Idea How to Deal With Iran,” New York Times, November 16, 2007, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/11/16/opinion/saudi-iran-strategy.html.

- Benjamin Schraven, Bernhard Trautner, Julia Leininger, Markus Loewe and Jörn Grävingholt, “How Can Development Policy Help Fight the Causes of Flight?” German Development Institute(DIE), 2016, https://www.die-gdi.de/briefing-paper/article/how-can-development-policy-help-to-tackle-the-causes-of-flight/.

- The EU’s 50-million-euro package for Iran aims to address the country’s key economic and social challenges. Although a good initiative, this package is insufficient in responding to the challenges mentioned above, both in its scope and target. See European Commission, “European Commission adopts support package for Iran, with a focus on the private sector,” press release, August 23, 2018, https://ec.europa.eu/europeaid/news-and-events/european-commission-adopts-support-package-iran-focus-private-sector_en; see also Esfandyar Batmanghelidj, “Here’s How the European Commission Will Allocate EUR 18 Million in Iran,” Bourse & Bazaar, September 12, 2018, https://www.bourseandbazaar.com/articles/2018/9/11/heres-how-the-european-commission-will-allocate-eur-18-million-in-iran.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).