For many Americans, daily life orbits around a high-speed Internet connection. Workers and students go online to communicate and learn. Families stay in touch through live video feeds. Job seekers often need an electronic resume and an email address for applications. Smartphones put maps, social networks, and video streams in people’s pockets. The American economy has gone digital.

Yet, the rapid transition to online content and services comes at a price. Buying cheaper goods directly from wholesalers, immediately accessing government services, and finding employment opportunities are increasingly only available to those who have an online connection. As a result, individuals without a private Internet subscription or digital skills are at a disadvantage when it comes to accessing economic opportunity.1 Individuals with digital skills but no private broadband subscription –likely due to the United States’ relatively expensive broadband service—must spend extra time getting to public connection points, such as libraries.2 And since everyone cannot regularly access the Internet, government agencies must operate both digital and analog systems, and private businesses miss out on an expanded customer base.3

There is no question that the Internet is a huge boon to the economy and society, but maximizing its potential is only possible if all individuals are online. As a result, it is critical that policymakers closely track broadband adoption rates: the share of households with a DSL, cable, fiber optic, mobile broadband, satellite, or fixed wireless subscription.4

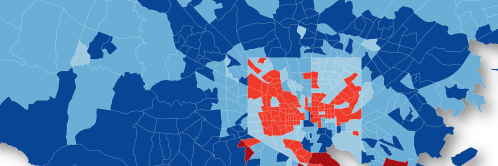

Until now, public, private, and civic leaders have frequently concentrated on broadband adoption at a national or international scale, looking at how rates vary across large segments of the population.5 However, new survey questions from the U.S. Census Bureau enable analysis at the metropolitan scale, creating new ways to measure and understand where America falls short in getting people online. This subnational approach is especially important because local and state governments play a lead role in guiding Internet policy, including infrastructure deployment, public outreach, skills development, and affordability programs.5

This brief uses 2013 and 2014 American Community Survey data to track current and changing broadband adoption rates at the metropolitan scale, while using a combination of other Census and Internet speed data to model what factors affect metropolitan adoption rates. In turn, the results of this analysis have clear implications for efforts to address the significant gaps in American Internet adoption.

Further information on the analytical approach and methods is available in the appendix.

-

Footnotes

- The term “digital skills” is used throughout this report, but is sometimes referred to as digital literacy or digital readiness. For more background the subject and statistical assessments for middle skill jobs, see: “Crunched by the Numbers: The Digital Skills Gap in the Workforce,” Burning Glass, March 2015.

- The National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA) analysis found that 28 percent of non-subscribers list price as their primary reason for not subscribing to in-home internet. This may relate to the United States’ expensive broadband service when compared to other OECD countries. Sources: National Telecommunications and Information Administration, “Exploring the Digital Nation: America’s Emerging Online Experience,” June 2013; the OECD broadband data portal is online at http://www.oecd.org/internet/broadband/oecdbroadbandportal. htm [accessed October 2015].

- Julia Greenberg, “Why Helping the Poor Pay for Broadband Is Good for Us All,” Wired, May 31, 2015. Available online at http://www.wired.com/2015/05/helping-poor-pay-broadband-good-us/ [accessed October 2015].

- This brief uses the Census definition of a broadband subscriber. However, there are competing definitions based on the speed of service and fixed versus wireless access. In addition, this definition was informed by requirements in the Broadband Data Improvement Act, passed by the U.S. Congress in 2008.

- See Table 1 and pages 13 -16 in: Government Accountability Office, “Broadband: Intended Outcomes and Effectiveness of Efforts to Address Adoption Barriers Are Unclear,” GAO-15-473 (Washington, 2015).

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).