Schools have historically been the beneficiaries of public and private sector investments in digital infrastructure, programs, and other resources. Funding has been primarily directed at in-school internet connectivity, after school programs and a wide range of related activities, including teacher professional development, e-books, and on-site computer labs. One of the largest sources of technology funding is the Federal Communications Commission’s (FCC) E-rate program, which invests in internet access and infrastructure in schools, including Wi-Fi. The 21st Century Community Learning Centers program, which was created in 1994 through a reauthorization of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act, also supports technology education for students during non-school hours. Combined, these federal programs have allocated nearly $86 billion in the last 23 years that can be added to numerous investments from philanthropic organizations and corporations.

However, getting internet to the school is just one piece of the puzzle in closing the digital divide and the growing “homework gap” in which students lack residential and community broadband access.1 Even in communities with exceptional broadband in their schools, how are student experiences affected when nearby institutions and establishments, including libraries, churches and other public facilities, have limited digital resources and connectivity? How does this impact students’ ability to share the digital experiences learned in school to the community?

The paper relies on data collected from visits to schools in two different cities—Marion, Alabama, and Phoenix, Arizona.2 Both schools were the beneficiaries of the ConnectED initiative (ConnectED), which was launched under the Obama administration to accelerate on-site internet access and teacher technology training in 2013. Public and private sector partnerships were at the center of ConnectED with participating entities providing financial support, equipment, wireless infrastructure upgrades, and software donations to eligible schools and libraries. Apple, Inc. was one of many corporate participants in the ConnectED initiative and provided the two schools profiled in this paper with tablets, software, and professional development workshops.

Given the availability of technology within each school, I explore how the in-school digital experiences of their students compared to access and use within the surrounding communities, especially among libraries, community-based organizations, and local businesses. More specifically, I examine both the availability and capacity of local entities to close the homework gap and the much broader digital divide in historically disadvantaged communities.

While this paper provides detail on how each school implemented their partnership with the Apple and ConnectED initiative, my primary focus is on the school and community connections, especially as students’ technology use is often contained within educational institutions. I conclude the paper with a series of proposals and programs to bridge these local divides that are stifling robust digital interactions in low-income communities.

The White House ConnectED initiative

In the 1990s, lively debates on the digital divide ensued, largely focused on strategies to enhance public computing access, equipment, and software and digital literacy training for providers and users. Former deputy administrator of the National Telecommunications and Information Administration, Larry Irving, coined the term “digital divide” to compare the experiences of those who were online with those who were not.3 These citizens were disproportionately people of color, foreign-born residents, high school dropouts, older Americans, and rural residents.

A steady stream of federal, state, and municipal support would soon follow, going to community technology centers (CTCs) to address these digital access disparities. Government resources, including those allocated from programs like the former Broadband Technology Opportunities Program (BTOP) administered by the U.S. Department of Commerce, primarily supported the expansion of CTCs, which were often created and operated by community and faith-based leaders. Private philanthropy later supplemented BTOP by providing additional grants to CTCs and other community-based organizations focused on closing the digital divide.

Generally, the programmatic efforts happening in schools and communities were established to address the persistent divide, which still affects more than 10% of U.S. citizens who either do not have access to high-speed broadband or have no general interest in technology.4

Parallel to the conversations on community technology were ones related to expanding digital access in schools, resulting in a plethora of resources. This included smart boards and other in-classroom devices, online messaging tools, and interactive web-based tools for educators, parents, and students. Professional development for teachers was also a priority as more schools adopted new technologies with the goals of introducing new pedagogical frameworks for classroom instruction.

“New industries, including those empowered by artificial intelligence and machine learning algorithms, are quickly transitioning citizens from an analog to a digital economy.”

Today, innovation is steadily increasing as evident in new online products, services, and platforms. New industries, including those empowered by artificial intelligence and machine learning algorithms, are quickly transitioning citizens from an analog to a digital economy. However, American students fall behind their peers from China, South Korea, and Singapore when it comes to creating and working in this new gig economy. While some research argues that the global disparities are due to the lack of access to universal, high-speed broadband networks in the U.S., the availability of devices, teacher readiness, and earmarked resources to expand digital proficiencies can also be blamed.5 Further, the homework gap—a term coined by FCC Commissioner Jessica Rosenworcel—is rapidly widening as schools and communities fail to develop digital bridges into the places where students live.6

In June 2013, the Obama administration created the ConnectED initiative after learning that teachers in certain communities were often experiencing subpar internet access compared to other American households.7 The program goals were to fix disparate online access for students in public schools, with a specific focus on unreliable and slow internet that was preventing teachers from effectively using technology in the classrooms.

When first announced, ConnectED’s explicit goals included:

- Connecting more than 99% of students to the internet in their schools and libraries at speeds of no less than 100 megabits per second (Mbps) per 1,000 students at a targeted speed of 1 gigabit per second (Gbps) by 2018.

- Creating partnerships with the private sector and nonprofit organizations to make affordable devices available to students.

- Training teachers to incorporate technology into the classroom.

One year after its announcement in 2014, the private sector quickly reacted and joined the administration’s effort, including Apple, Microsoft, Verizon, AT&T, and the Sprint Corporation. Since the program’s start, Apple has awarded $100 million in in-kind donations, including hardware, software and necessary Wi-Fi and other infrastructure upgrades. Participating schools, including the ones surveyed in the paper, have received iPads, software, and teacher training as part of Apple’s competitive, national grant program.

Research methodology

As part of my research, I chose to focus on two awardees of the Apple and ConnectED program, largely due to the presumption of existing technology resources within the school. The first case study is on Francis Marion School, a pre-K through 12th grade consolidated school in Marion, Alabama, and a program grantee since 2016. The student body of Francis Marion School is 98% African American, and predominantly low-income. The school is in the Perry County School District, a highly rural community that is approximately two-hours from the city of Birmingham. Perry County has a long history of fighting racial segregation. In 1966, the school district was part of a landmark state desegregation case after the noticeable concentration of Black students in public schools.8 The history, along with its location, made the inclusion of Francis Marion unique, along with the size of the student population (700 students). Francis Marion students were also able to take their devices home because of available broadband service on their iPads (a program to be discussed later in the paper).

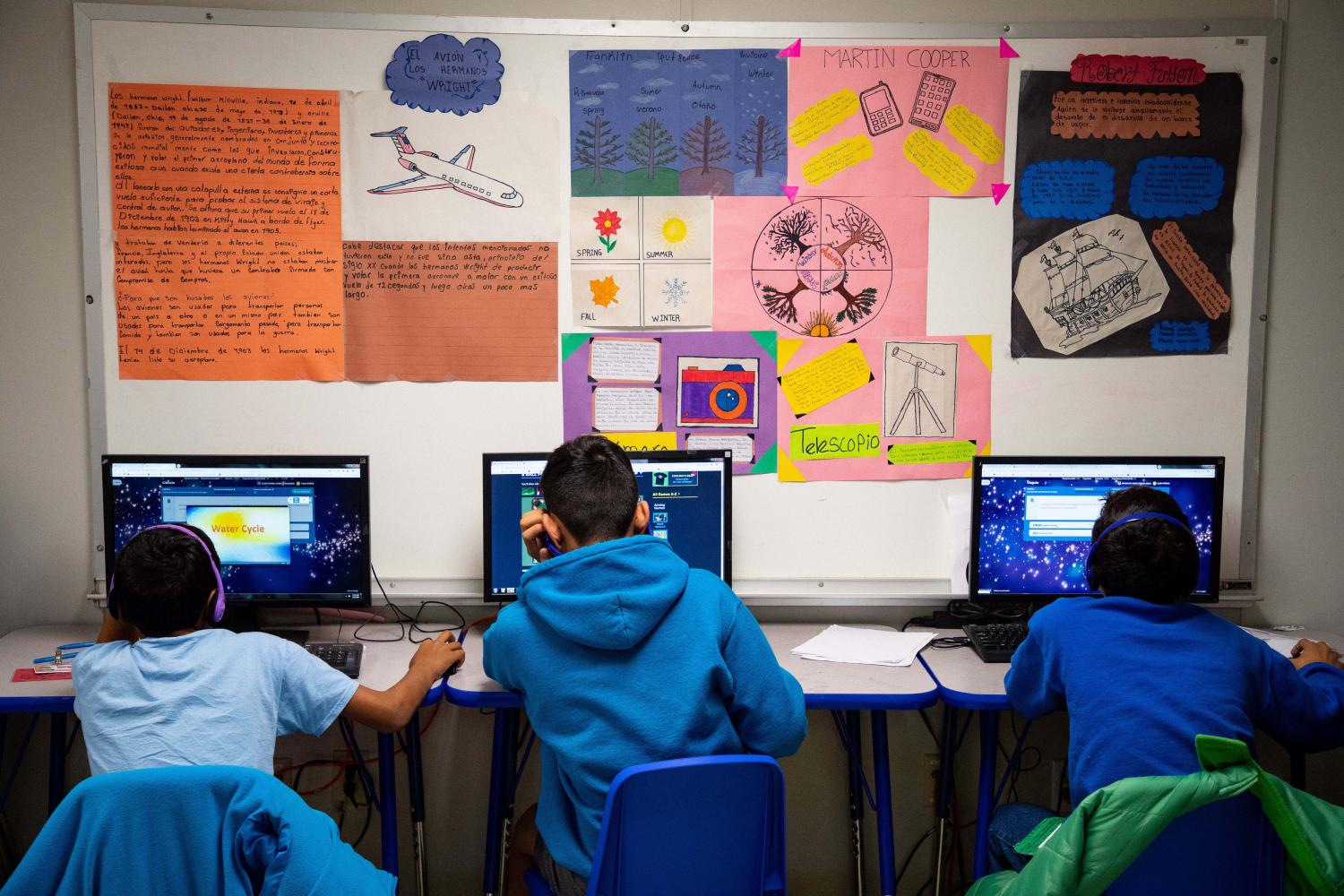

Pendergast Elementary in Phoenix, Arizona, is the second case study for this research and another grantee since 2016. Pendergast received iPads for all students and benefited from three years of professional development training from Apple. Unlike Francis Marion, Pendergast students were not permitted to take their iPads off campus.

Located in Arizona’s Maricopa County, the student body of Pendergast Elementary is 95% Latino, and majority low-income. The school is in the western outskirts of downtown Phoenix with a large population of undocumented immigrants. Maricopa County has an embattled history of villainizing immigrants under the leadership of former Sheriff Joseph Arpaio, who was notorious for racially profiling and detaining Latinos in the Phoenix area.9 After 24 years in office, he was unseated and sentenced to prison for his unfair and unconstitutional treatment of Latino residents, many of which were not legal residents at the time.

In addition to their demographic differences, I also chose each school because their respective local communities have a vast range of local assets, including libraries, local businesses, and nonprofits. This information was ascertained prior to actual field visits through an online search.10

For each case study, data was compiled through direct interviews with principals, teachers, parents, and community leaders. Students were not interviewed for this paper, but observational data may be shared.11 Prior to the start of the site visits, research permissions were sought and approved by district superintendents.

The next section provides case studies of each school, relying upon the qualitative data collected during the interviews and field visits. Following this section, common themes and recommendations for improving community digital access are shared, including active legislative proposals.

Francis Marion Elementary School

Overview

Alabama ranks 47th or below on reading and math scores for the 2019 National Assessment of Educational Progress.12 In Alabama, 59% of students are white, 33% are African American, and the remaining percentages are other racial and ethnic groups.13 Of all students in Alabama public schools, 52% are economically disadvantaged. The state’s Department of Education shows reading, math, and science proficiencies generally fall slightly below 50% for all categories. The graduation rate for the state is roughly 90%, with about 75% of students ready for college, according to state standards.

“Of all students in Alabama public schools, 52% are economically disadvantaged.”

Francis Marion School, one of two schools in the Perry County School District, is a consolidated pre-K through 12th grade school with 694 students, 99% of whom are African American.14 More than 70% of the students are economically disadvantaged. The students’ performance in core studies, including reading, math and science, fall at 23%, 19%, and 15% respectively, ranking near the bottom of Alabama schools on standardized test scores. Despite these low scores, 92% of students graduate with a little over 50% ready for college.

In Perry County, broadband access is at an all-time low, with only 39.8% of households being connected to the internet, according to U.S. Census Bureau data from 2013-2017. Alabama ranks 41st in the nation in terms of broadband connectivity and download speeds.15

The school’s principal is Dr. Cathy Trimble. She was born and raised in Marion, Alabama, and has been in the district for almost 30 years. Before becoming principal, she only left the city for college and soon returned after her now-husband became the school’s physical education teacher. Dr. Trimble started as a substitute teacher in the Perry County school system, and over the last three decades worked her way into the role of the school’s top administrator.

At the time of the proposal submission to Apple, the school was only serving high school students. Soon after the grant was awarded, the school went on the state’s failing list and risked closure. The district immediately drafted the plan for the school’s consolidation, which now enrolls students from pre-K to high school. The resources were successfully redirected to the consolidated school, which makes their case study unique because of the school’s size.

In 2016, Francis Marion School received 700 iPads as part of the program; the inventory is still the same in 2019. All students receive an Apple iPad as part of their classroom experience and can take them home at the end of the school day. Dr. Trimble fought through racial stereotypes in her decision to permit home use. “Because we are African American, people thought that [the students] were going to sell or lose their iPads,” she shared. “But, in one year, we may have lost two or three and one of them, someone [in the community] called and told me [the location of one of these iPads].”

As mentioned, internet access is not readily available in Marion, Alabama. On my drive into the community from Birmingham, the two-lane road was flooded with colorful signs marketing cheap internet offers. Dr. Trimble considered the lack of home broadband access as a primary reason for her decision to allow home use, recognizing the potential of the device to have a multiplier effect in the students’ household. The equipment at Francis Marion is also bundled with AT&T broadband service so that the students and other family members can also access the internet at home.

“Before the program, I would come to the school on the weekends and see parents pulled up in their vehicles using the school’s Wi-Fi,” Dr. Trimble stated. “When we first got the iPads without the broadband package, kids would still be sitting on the ground or on the stoop, doing their homework or studying,” she continued. With some ingenuity, she brokered the deal with AT&T, ensuring that her students had access to Wi-Fi during the school year.

Creating digital norms in schools

Some researchers have argued that having effective leadership in schools is the first step in the slow acculturation to and adoption of technology.16 The leadership drives the vision for school technology use to energize participation by amplifying the critical importance of digital resources. Integrating technology into the existing culture of the school was challenging, according to Dr. Trimble. At the program’s onset, she had to encourage teachers, students, and parents to use the technology, and develop new teaching methods, which was very uncomfortable for many of her teachers. Thoughtful in her choice of words during the interview, Dr. Trimble detailed how she walked each group through the transition, starting with the basics on how to turn on the tablet.

In their research, Tyler-Wood, Cockerham, and Johnson (2018) share the difficulties that new technology presents in rural schools: less-equipped teachers and other disparate physical resources make technology integration more difficult in rural schools, layered on top of insufficient funding.17 Francis Marion is no exception. Parents were brought into the program at the start to not only gain buy-in, but also to identify their own needs. Parallel with the program’s implementation, the school instituted a parent computer lab where adults could fill out job applications or conduct other online business. Students were also empowered to manage the lab and work with teachers to secure the school’s computer equipment against viruses. Dr. Trimble called these “baby steps” to help stakeholders gain “the basics of the basics” after realizing their low levels of digital proficiencies.

Staff development is also a critical element of the school’s success, according to Dr. Trimble. Further, an organizational realignment to accommodate the technology helped her to create and shift roles among some faculty to ensure positive outcomes. A science teacher at the school, Gylendora Davis, was given the joint role as a tech and media instructor. In my interview with Ms. Davis, she supported the principal’s technology integration plan:

Students already know some of this stuff because they have cell phones. Dr. Trimble has just made it mandatory to bring technology into our lesson plans. There are some challenges with us, teachers. We had to figure out a way to put a lesson into our regular curricula and use some of the available online content on the iPads.

Francis Marion is empowering their teachers to look beyond the traditional subjects associated with technology, including math and science to the arts, music, and writing areas that are usually less technical. “Our students are coding, learning robotics, and also engaging the arts,” Dr. Trimble shared. “Sometimes, it’s not uncommon for the students to even lead the teachers on ideas of what to cover.” Her students are also using more advanced technology applications, such as designing QR codes for research projects and using iMovie for storytelling.

Going fully digital in classroom instruction is an aspiration of the Francis Marion School. “What we have now is a prelude to what is to come,” Dr. Trimble predicted. “I see us progressing to a mobile music program where the band director can help students learn how to play instruments from mobile devices. Marching bands are popular here in Alabama that would be such a complement to what the kids can do now.” Unlike schools that struggle to maintain technology as a core part of science and mathematics, Dr. Trimble’s extension into the humanities and arts may be able to foster increased adoption by both students and teachers.

“In this rural town of Marion, the optimism around the technology in the school is going viral among students, teachers, and parents.”

In this rural town of Marion, the optimism around the technology in the school is going viral among students, teachers, and parents. In my observation of students exiting the building at the end of the day, most of them had an iPad under one arm and a mobile phone in the other hand, suggesting that the school’s culture is embracing digital use. One of the fifth-grade teachers supported what I saw by saying: “[The school] starts early to give these students the right values around the use of technology. Most of the students have phones, but we want to show them what the world will be like with forthcoming virtual and augmented realities. We are not stopping.”

Research suggests that African Americans access the internet via their mobile devices at a much higher percentage compared to white individuals.18 Moreover, these populations tend to be “smartphone dependent,” relying only upon their mobile device as a gateway to the internet. While such access can be promising, some of the challenges with the homework gap refer to students’ inability to use their phones to complete research papers or other assignments that require more robust internet and device access. Fluctuations in monthly costs can also lead to more service interruptions for this population, resulting in less consistent access for lower-income households.19

The ability to complement smartphone access with a tablet may serve to lessen the barriers to broadband adoption at home and in the school. A 2008 study from the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System reiterated this point by concluding that teenagers who have access to home computers are 6–8 percentage points more likely to graduate from high school than teenagers who do not have home computers.20

Dr. Trimble shared her plans for sustaining the momentum of her students’ technology use for the next few years, given the formal partnership with Apple ended in the summer of 2019:

Next school year [2019-2020] will be the first time without Apple and their program. The students will still have their tablets and we have now built the technology into lesson plans. Going forward, we have teachers who are ready to further customize the curricula to the different grade levels. When we gave the tablet to the high school students, they saw it as a new way to get on social media, but now, we are pushing it toward college applications. Last year, 100% of our graduates went to college. So, we have to keep going.

Given the school’s commitment to contributing to the learned digital experiences of its students, what role does the surrounding community play in reinforcing these goals? In what way can technology access in schools become a catalyst for expanding local access?

Making tech the new normal in Marion

It’s no question that technology access within the Francis Marion School has been a game changer, forcing a new level of digital engagement and responsibility among students and faculty. However, these digital accomplishments are not necessarily changing the broader community.

“We are doing such a good job [at the school] that many of these students are deciding not to return home,” Dr. Trimble shared. What she is referring to is the increasing exodus of families from Marion in search of new opportunities, especially given the downward turn in the local economy. “This town used to be thriving,” Dr. Trimble stated. “The plant for Mercedes Benz [in nearby Tuscaloosa] used to be a reliable source for jobs before it closed. Now, some students are traveling within the South and even above the Mason-Dixon Line to attend college. In some cases, students are leaving school early to go with their parents who are finding work outside of the city.”

During the interview, one of the parents, Twanda White, stopped by the office to let the principal know that she accepted a job in Selma, Alabama. Twanda was moving immediately with her children just one month into the school year. “I’m going to miss this school and Dr. Trimble,” she said. “My son was not doing well last year, then he got an iPad and he was able to get his grades up because he got more interested in school. I remember telling myself, the principal has taken my child from me because he always wants to be at school.”

When asked about her own technology literacy, she continued, “I already know some things, but the program here has helped me to do things like apply for jobs, send my references, and track my application.” Unfortunately, it is the lack of access to livable-wage jobs in the city that make it impossible for single parents like White to survive in Marion.

While one might think that the existence of technology would be transformative by itself, a mismatch exists between these added resources, the broader impact on educational achievement, and insufficient local opportunities—particularly jobs.

For example, Francis Marion is on Alabama’s failing school list, despite having access to such robust digital resources and cultivating increased student engagement. “I almost feel inadequate,” Dr. Trimble stated. “We have successfully changed the culture of the school, but our test scores don’t reflect this.” States like Alabama still rely upon traditional learning metrics and assessments to rank city schools, particularly test scores. Alabama also publishes a state report card on a school’s progress in terms of student attainment. Francis Marion is on that list.

Race may be a factor in this distinction from other schools. Jim Crow laws established a legacy of historically segregated schools in the South, which could explain the high ratio of African American students at Francis Marion. While explicit educational discrimination was outlawed in Alabama, segregation is now driven by income and wealth inequalities, causing communities like Marion to have more concentrated populations of lower-income students.21 The school is also nearly 100% African American because many affluent white families in the community send their children to the local private school.

While the technology program appears to have increased student engagement, research also concludes that it is not a catalyst for improved test scores, or at least not immediately.22 Digital access alone cannot dismiss the structural and social discriminations affecting communities of color. But, the case of Francis Marion suggests that it can improve upon school culture and drive some level of student engagement by empowering teachers to be more creative in classroom instruction and equip students with new tools. As suggested in conversations with Dr. Trimble, having access to technology breaks the mundanities of living within Marion where opportunities are limited.

From my observations, Dr. Trimble is committed to improving upon the life experience of her students and stands firm in her conviction to the school:

I feed these children when they are hungry. I cry with them and their families when they are going through something. I used to complain about them to the teachers. But, somehow, God just won’t release me from here.

For communities and students to be full beneficiaries of digital technology, it also seems natural to share these online experiences within their respective communities, thereby building local capacities and creating shifts in acceptable digital norms and practices.

However, three months out of the school year, or on summer break, Francis Marion students are without their iPads. “The kids in this community do not have a lot of places to go, and I know that they wait for the iPads to return,” she said.

The divide between the community and school

Marion, Alabama, resembles other rural towns. The usual temperament of the town enveloped by farms and green pastures is quiet. Sounds do make it into the more bustling commercial district where local businesses sit across from City Hall and the local library. A few blocks from Main Street is a tall water tower inscribed with the town’s name, which marks the town’s boundaries.

The library in Marion has computers and patrons have full access when it’s open. On the day of my visit, the library—which is about two to three miles from the school—was closed. Dr. Trimble shared that the library is a main resource for the students, if they can get there. Common transportation barriers or an unavailable parent or guardian stymie continuous traffic to the local institution.

Across from the public library is The Social, a newly opened ice cream parlor. The building blends into the row of antique stores and sits next to a Southern-cuisine restaurant. As described by Dr. Trimble, The Social is just that—a place for ice cream, board games, and internet access. It is new to the community and when I walk in, the large space is lined with rectangular tables from the entrance to a few feet before the ice cream parlor. A high-top table surrounds the walls of the space with appropriately sized chairs for use. Board games are scattered on tables and a sign invites patrons to use the Wi-Fi.

The owner is an African American woman, Betty Cadore, who sold her house in Bridgeport, Connecticut to relocate to Marion one year ago. “My daughter was working here as a Teach for America fellow. I came to visit her and loved the community so much that I moved,” she shared. “Local people didn’t think that we would last,” she continued. “But we are still here.” Aside from her daughter, who now works at Francis Marion, the Cadores have no family connections to the town except through the family business.

In addition to ice cream, Cadore also provides breakfast to local kids on their way to school. One of her daughters commented, “My mom is here at 6:30 am every morning. She saw a need for breakfast and wanted to provide that for the young people.”

While schools are abundant with resources primarily earmarked and targeted to educational gains, surrounding communities lack the digital infrastructure to support the technology training that happens within schools. Getting to any of these places may also require some form of transportation.

“We sometimes have more white people here [at The Social] than [Black] students because they have no transportation,” Cadore pointed out. “I really wish that I could figure that problem out because we are here to offer a safe space for the kids to do their homework.” From this statement and the general case study findings, it was also clear that there were not too many places that offered Wi-Fi or fixed broadband services to community residents.

Francis Marion’s experiences closely resemble the findings at the second school, Pendergast Elementary School in Phoenix, Arizona.

Pendergast Elementary School

Overview

The district that houses Pendergast Elementary School has 13 schools that enroll pre-K to eighth grade students. The district has 9,753 students and 500 full-time equivalent teachers, creating a student-to-teacher ratio of 19.5. In 2018, per student spending in the district was $7,438, compared to $8,269 statewide. In 2017, average spending per student in Arizona was the fourth-lowest in the nation.

The students at Pendergast Elementary are predominantly Latino, many of them the children of undocumented workers. Of the 813 students at the school, 85% are of Hispanic origin. In state math assessments, 29% of students in grades 3-8 scored “proficient” or “highly proficient.” In science, only 39% of students “meet” or “exceed” state requirements.

The school building overlooks the mountains, complementing its open architecture and LEED compliance. Pendergast is a green school with eco-friendly student work stations scattered around campus. Technology access is prevalent at the school. Students have access to a 3D printer and in-classroom smart boards.

When walking into the school, the faculty were welcoming. The receptionist behind the first entry way has a nameplate on her desk that reads: “Like a boss.” Students in school uniforms appear to embrace her title as evidenced by the number of them approaching her for help. There is a constant exchange of “excuse me” and “thank you” as I wait for the principal. Arizona state law bans the use of bilingual education, so everything is taught in the English language.

Getting the school connected

Principal Mike Woolsey is an almost “lifer” like Dr. Trimble. For decades, he has been the principal at Pendergast and a resident of Phoenix. Like his counterpart from the rural South, he wants to leverage the technology to ensure that his students have exposure to 21st-century tools and jobs. He applied for Apple’s competitive grant program with the goal of expanding the horizons of students. “I wanted our kids to have options [so] that they are not stuck, unless they want to be,” he asserted. “Many of their parents didn’t finish school. I want my students to thrive instead of survive in this world,” he continued.

When Principal Woolsey wrote his grant to the Apple and ConnectED initiative, he started with the assumption that most of the students had smartphones. His teachers were already depending on these devices to assist with homework. “We don’t send a lot of homework home,” Principal Woolsey shared. “But what I have done is to enable applications on smartphones since most students have them.”

Like African Americans, Latinos also have a heavy reliance on smartphones. Approximately 25% of Latino populations are “smartphone dependent” and use their mobile device as their only gateway to the internet.23 In addition to accessing basic services, this population uses their devices for email, entertainment, government services, health care, and other relevant functions. But like Francis Marion, students with only smartphone connectivity may be challenged in completing research papers or other extensive assignments.

The school received the award from Apple in 2016. Since then, the iPad program has provided a cushion between students’ smartphone use and their lack of home PC access to generate more interest and engagement in the digital economy. Mobile access is important in this community of immigrants—many of whom are undocumented. Principal Woolsey shared how the egregious acts against immigrants have affected his students:

First, some of my parents are afraid to drive their kids to school. They drive with their passports in hand because of the fear. Maricopa County had a bad reputation because our neighborhoods were targeted by coyote people 10 years ago and had to pay ransoms.

He continued: “Most of the students and their families have mobile phones for safety. Our parents are afraid to leave the house. Here, a phone is about safety and staying in contact with that child.”

Like Francis Marion, Pendergast undertook several steps to design and implement its one-to-one technology solution, starting with a formal plan. “You have to plan for the technology with an implementation plan that you can revise,” continued Principal Woolsey. “And, you shouldn’t put in place a plan of tech to just substitute paper.”

At Pendergast, students in certain classes can take home their devices, including those enrolled in STEM classes. Unfortunately, not all students have broadband access at home. Cox Cable has a low-cost broadband offering, but the school is unsure of how many households subscribe. For Principal Woolsey, the main implementation of technology happens on campus.

On the point of local broadband access, Ruth Roman, the library media technician, commented, “Most parents do not have internet at home. Every year, we have a hard time getting the parents to complete the required paperwork for free or reduced-price lunch as a result.” Referencing Cox’s low-cost program, Roman shared that subscribers that she knows are usually signed up on a “pay as you go” basis.

Being an Apple and ConnectED recipient has helped the school to reach some of their technology goals. Both Roman and Principal Woolsey agree that the school quickly benefited from the program’s equipment and software donations, as well as the structured teacher training. Reflecting on his school’s experience in setting up the program, Principal Woolsey stated: “We were able to upgrade our network. There was so much to do, but each time we got better at it.”

Like Francis Marion, stolen devices among the student body are not an impediment at Pendergast. “We have had these iPads for three years and had zero theft,” he shared. “There will always be fears versus benefits. In my opinion, the benefits outweigh the fears.”

Teachers at Pendergast underwent a paradigm shift related to the use of technology in the classroom. The principal had to first get buy-in and then work to phase in aspects of the new applications, software, and hardware. Beginning with the expansion of the role of library instructor and technician, the school quickly put in place policies and infrastructure, including a mobile iPad cart that could be transported to each classroom.

Eliza Oldham, the technology teacher for kindergarten through eighth grade, led the efforts to connect parents to the program and address their fears about technology. She shared during her interview that the program has helped young people in the home teach their parents about these online tools, making it more comfortable for the parents. In her research, Katz (2010) found that while media experiences have primarily benefited more affluent communities, they can generate more trust within immigrant communities when young people serve as brokers to online information.24 In a survey of parents and children in an immigrant community in Los Angeles, her findings demonstrated that children’s use of traditional and newer forms of media helped in the settlement of their families.25

“At Pendergast, technology access has also encouraged students to explore STEM careers.”

At Pendergast, technology access has also encouraged students to explore STEM careers. “[At the school], we tell the students about jobs in coding and help them with resumes to get them started on their job search,” said Ms. Oldham. Additionally, the technology program at Pendergast Elementary School is also used to provoke problem-solving among students, an action favorable to teachers.

Mr. Quinones, a fifth-grade teacher, used his iPads for a research project where the students had to identify and write about women of color in the community. While his students couldn’t take their devices home, they used the time in school to engage in cultural and ethnic studies research. Once the project was completed, they shared their presentations with the subjects of their research.

The class project was a success for students and community leaders, despite some parents not attending. In response to this, Mr. Quinones shared: “We need a program for adults so they can see what we do at school. We want them to be able to help their kids.”

Tech exposure and test scores are not aligned

Having robust exposure to digital resources does not lead to improved test scores at Pendergast, nor is it proven anywhere else at this time. While interviews with the principal and teachers suggest a more collaborative approach to learning can be beneficial, their students still lag others in state test scores.

Like Dr. Trimble in Marion, Principal Woolsey experiences the same type of disbelief around how local schools are assessed under rigid state standards—despite huge investments in new digital resources. “Our states still seem to see these things as black and white,” he commented. “We are teaching our kids how to thrive and not survive in the new economy, yet when it comes to testing, they can’t compete with other schools and other districts. For some of my students, this is their first experience in a formal school setting.”

Pendergast’s large immigrant population largely contributes to the school’s rank, but this phenomenon is not unfamiliar among schools in low-income areas whose achievement gaps are already well documented. Moreover, educational research suggests very little correlation between technology access and test scores. In 2019, a report by the Reboot Foundation found that test scores decreased for fourth graders who used tablets in “all or most” of their classes.26 However, some variance appeared among students when the technology was used for research, problem-solving, or complimented some other critical thinking skill.27 While more research needs to be done on whether technology can be a catalyst for improved test scores, both principals identified an increase in student engagement, which could be an interesting correlate itself.

A 2019 Gallup study on student creativity found that teachers who leveraged technology to assign “creative, project-based activities” experienced more positive responses from students, including higher self-confidence, and improved critical thinking and problem-solving skills.28 While the merits of such performance could be argued, these findings suggest an increased level of student engagement as demonstrated at both schools at the core of this paper. As Principal Woolsey described, “We want to push our kids to do more extended things that go way beyond their personal experiences.”

This part of Phoenix is a digital desert

However, limited resources available in the surrounding community can impact the students’ digital learning. “We need more involvement from the community,” Principal Woolsey stated. “Kids have TVs at homes. They need access that will help them improve their lives. Every app that we use at school should be able to go home.”

The surrounding community is without many local resources for students when it comes to online access. Only 79.6% of the households in Pendergast’s school district have broadband subscriptions, despite the city of Phoenix being among the most connected cities in Arizona.29

More than a half-dozen pawn shops, liquor stores and used-tire establishments line the main streets around the school. Given the school’s location, a car or sufficient public transportation is needed to get around. The school assistant, or “the boss” shared, “Students’ households lack adequate transportation and because of the climate, they do not walk. It’s too hot. And when they have internet access at home, most of the students go on[line] for entertainment.”

There are two local libraries near the school—each approximately five miles from the school on opposite sides. I visited one—Desert Sage Library, which took me approximately 15 minutes to get to by car. Like schools, libraries have also been recipients of grants to bring more access to communities. In this library, more than 20 computers were lined between the books and the walls. People were actively logged in and the location was extra quiet as patrons maintained their focus on their screens. In front of two librarians was an African American woman who was trying to renew a library card but was told that she had to go online.

Her name was Francis and she had just moved to Phoenix to escape the cold weather in the northeast. She was recently separated from her spouse and patiently waited for her son to finish playing a game on one of the library stations. When asked how she would ultimately obtain her card, she shared that going online would be her best bet, but she’d have to wait to use her son’s phone. She gave it to him for emergencies at school.

“You can’t do nothing without being online,” Francis said. “Social services prefer that you go online and now the library. If you want to apply for a job, go online. Everything is digital and a lot of older people don’t even know how to do it.”

In many ways, Francis speaks to the challenges that the Pendergast teachers shared. There is a huge digital divide within local communities that restrict the full use of new technologies. In the case of adults, they have to learn as they go, or as Francis put it, “I need to rely on my son to help me get things that I need online.”

Francis also shared the challenges of doing everything over a mobile phone. “If you do it, like internet surfing, on your phone, it’s a cost [in terms of data] and I’m not working right now, so this all adds up.” She is aware of the low-cost broadband program available through Cox, but for someone on a limited income, that is still more than she can afford. Her son is in high school, so he cannot participate in the iPad program. Instead, he has a Chromebook provided by the school district to which she directed some reservations: She’s not sure if he’s using it for homework or gaming.

However, Francis understands the importance of being connected. Recently, she visited her doctor and was given an advanced stage cancer diagnosis. Because the doctor was able to reach her on her son’s phone, she was admitted to treatment immediately. “My doctor put all of my records online, through something like My Chart,” she recalled with half of a smile. “And, here I am today getting treatment.”

The need to support the intergenerational use of technology is obvious from my interview with Francis. Deploying technology between the schools and communities can potentially create a multiplier effect that not only amplifies in-school investment, but also builds the individual and community capacities necessary to thrive in an increasingly digital economy.

Bridging local divides between schools and communities

In a lofty illustration, the two case studies suggest that the inside of the schools appear to have a few gallons of water, while the community—though rich in family and institutional connections—is dehydrated or thirsty. As a result, some residents are compelled to relocate despite the positive effect the school’s technology program is having on their children. Or, residents may be digitally stuck because the robust and contained use of technology within the school does align with absent local opportunities. Overall, these communities are experiencing their own local divides, where the resources within schools are not often imparted into the surrounding communities, and vice versa.

Generally, what I discovered during both site visits is that Pendergast and Francis Marion have shared goals when it comes to the effective integration and adoption of technology by students, faculty, and some parents. Yet, they are sucked into educational models that restrict technology use to the facility, and as a result, are forced to measure student growth through traditional metrics.

Principal Woolsey described this challenge as feeding into the acts of survival that his families undertake from being fully disconnected. In Marion, students are similarly trapped within stalled local economies that fall behind the opportunities emboldened in the new information economy. In both case studies, school-based technology programs alone face obstacles to changing the economic and social trajectories of students. First, the current methodology for deploying digital access is school-centered. Second, the surrounding communities are digitally barren and unable to reinforce these digital experiences, or at best, keep these students connected.

Thus, creating a local digital infrastructure starts with mapping the available assets within a community, from libraries, community-based organizations, and local champions like Betty Cadore from The Social. In their research, Rideout and Katz (2016) pointed to the benefits in creating such local supports, primarily because they advance intergenerational cooperation and adoption of new technologies. Thus, there is a logical need for more engagement by local institutions, including libraries, community centers, and other gathering places, for families without home access to get online.30 Francis Marion is an exception when it comes to home-use of school devices. But not all schools can provide an in-home resource or have technology available at all, leading to increased inequalities that will only widen as the information economy becomes more widespread.

“Local libraries are not only the most visited when it comes to public computing, but they are the most utilized asset by individuals without home internet access.”

Local libraries are not only the most visited when it comes to public computing, but they are the most utilized asset by individuals without home internet access.31 In most rural communities, the library is normally the anchor of local activities, such as government services, benefits enrollment, and tax preparation services. Yet, some local libraries are still far from where some local people live, work, or go to school, thereby compromising their ability to do more. Librarians and other staff are also tasked with a variety of functions from checking out materials to helping individuals apply for jobs and access government services. Challenged by limited funding, staff, professional development opportunities, equipment, and software, local libraries can themselves become barriers to adoption.

Community-based organizations, including CTCs, and local businesses are also other local resources that permit free Wi-Fi use, like The Social and, in some cities, the local McDonald’s. However, these institutions also have limited times for availability, may require additional collateral (e.g., a library card or enrollment), or are restricted by limited bandwidth to available unlicensed Wi-Fi.

In the end, schools need connections to reliable, convenient, and safe local digital infrastructure, inclusive of libraries, community-based organizations, and even households to bolster their activities. This can address the growing divides that are quickly widening within low-income and rural communities.

The final part of the paper offers recommendations that make home and community internet access more readily available and supports intergenerational efforts to establish local digital norms around technology among certain groups. The next section also surfaces legislative proposals to advance community-based technology access that overcome the barriers associated with the homework gap.

How to enhance connections between schools and communities

1. Make community internet access available 24/7 to low-income students and their communities.

Several U.S. cities have deployed lending programs for Wi-Fi hotspots, in addition to providing computer centers. The New York Public Library launched in 2014 a lending program in response to a survey revealing that 55% of library patrons did not have internet access at home. For families making under $25,000, the percentage increased to 65%. Initially seeded through a $500,000 Knight News Challenge Grant, the pilot focused on public school students who lacked home broadband access and through additional donations targeted 10,000 households with internet access.

The Chicago Public Library has also deployed a similar initiative in three libraries that allow residents to check out a Wi-Fi hotspot like they would a book. By mid-2016, the library had 973 wireless internet hotspots for checkout through their Internet to Go program.

In addition, creative solutions to bring internet access to where students are is demonstrated in the wiring of local school buses. In 2013, the rural Coachella Valley Unified School District (Coachella Unified) in California was the first to provide iPads to every K-12 student as part of their mobile learning initiative. Because 95% of students live below poverty, they are challenged in their transportation to local institutions or do not have the economic means to subscribe to a monthly broadband service. In 2016, the school district equipped its school buses with solar-powered Wi-Fi routers to provide internet access while in transit. When stationary, the buses were parked within underserved neighborhoods to offer 24/7 Wi-Fi coverage.

Coachella Unified’s Wi-Fi on Wheels project has enabled broadband internet where students live to minimize the obstacles that disrupt use between the school and community. The program has resulted in a jump in district graduation rates from 70% to 80%, according to one study.32

In 2017, Google piloted a similar initiative, Rolling Study Halls, in the Berkeley County School District that enables broadband on 28 school buses. The program has since been expanded to 16 additional school districts and provides Wi-Fi routers, data plans, and devices for students to use while in transit.

Policymakers are finally understanding the need to empower local resources. In May 2018, Sens. Tom Udall (D-N.M.) and Cory Gardner (R-Colo.) introduced a bipartisan bill to equip school buses with internet access. The bill extends the FCC’s E-rate program—which provides schools and libraries with affordable broadband services—to reimburse school districts for the cost of outfitting their buses with internet access. In a press release on the bill, Udall stated, “It’s time to end the homework gap. Our legislation will help give all students the ability to get online to study and do homework assignments while they’re on the bus—a common sense, 21st-century solution.”

In 2019, Rep. Grace Meng (D-N.Y.) introduced a similar bill to reduce the homework gap. Meng’s bill, the Closing the Homework Gap through Mobile Hot Spots Act, would develop a $100 million grant program for libraries, schools, U.S. territories, and federally recognized American Indian tribes for the purchase of mobile hotspots. According to Meng’s press release, the mobile hotspots program would be established for students in need of internet access for homework completion. In her statement, she reinforces the need for such action:

Every child deserves their best chance at pursuing an education. But it breaks my heart knowing that millions of kids, every night, are unable to finish their homework simply because they are without internet access. Before the internet became ubiquitous, students completed their homework with pen and paper-today, that is no longer the case.

Taken together, these two bills can help scale and sustain many of the pilot programs being instituted within local communities while closing the homework gap. Although most of these programs rely upon philanthropic and private sector support, the adoption of federal legislation would bring more certainty in terms of appropriations and deployment, making these programs less vulnerable to political changes like the ConnectED program.

2. Create more intergenerational projects between schools and local communities to foster broadband adoption and use.

Between 2008 and 2011, the Mooresville Graded School District in North Carolina issued 4,400 Apple MacBooks to students in grades 4–12. Subsequent gains were seen in graduation rates from 80% to 91%, and students exhibited greater proficiency in reading, math, and science—73% to 88% overall. But their story, as some suggested, had less to do with the availability of hardware and more to do with the leadership and their plan for technology deployment. According to its website, the district continues to distribute laptops to its students. It has been the online content, teacher development, parent engagement, and student outcomes that make their technology program effective.

The same type of methodical deployment was adopted by both principals in my case studies. With the help of the Apple and ConnectED initiative, these leaders also revamped existing processes and staff roles to ensure a seamless integration of the technology into the classroom.

What’s even more comparable to the Mooresville lessons is the time spent by both schools on creating the trust of technology among students, teachers, parents, and other community members. In communities of color, intergenerational connections are fundamental to this process, especially as the parents and caregivers of students experience a host of other social problems. For example, when Dr. Trimble decided to allow her students to bring home their iPads, she was appealing to the intergenerational relationships within her community while enabling additional online activities for family members, such job searching, distance learning, among other functions.

Research has long supported the role of students in influencing parents to engage new technologies.33 When young people become “brokers” to new technologies for their parents and other caregivers, there is a higher likelihood of broadband adoption within the home and a greater exploration of the functionality of the internet (e.g., for health care, employment, and other critical decisions). Children are often seen as the most trustworthy source for families when it comes to internet use. In her research, Corea (2012) found that despite one’s demographic status (as defined by socio-economic status, income, family structure, among other variables), young people are the key agent for introducing and integrating technology into the home.34 Thus, the imperative to create more robust, local programs that enhance intergenerational engagement could be one of the bridges between schools and local communities. The fifth-grade research project at Pendergast was an attempt to pull the community into the school, which is an incremental step in creating a more digitally enabled community.

“When young people become “brokers” to new technologies for their parents and other caregivers, there is a higher likelihood of broadband adoption within the home and a greater exploration of the functionality of the internet.”

Other nationally known programs are attempting to build such bridges. For the last nine years, Comcast’s Internet Essentials program has been offering low-cost broadband to low-income families, using young people as digital connectors or local ambassadors for training and service within their respective communities. In some affiliate programs, students receive community-service credit or a small stipend for their efforts.

Establishing both trust and purpose for the technology is important for schools, community-based organizations, and other local institutions introducing digital resources.

3. Consider technology as a catalyst for increased student engagement in schools and communities.

Despite the availability of digital resources, schools like Francis Marion and Pendergast are assessed by stringent metrics, including student grades, test scores, and college enrollment. Low-income schools start with a deficit and consequently must catch up with more affluent institutions. While the an in-school technology program and available local resources should be ingredients for more effective learning, such goals are often unrealistic given the basis of cognitive retention around test scores and the institutional funding and staffing constraints for certain communities.

While the Apple and ConnectED initiative offered a framework for how designing and implementing a robust technology initiative, both principals faltered at changing overall student achievement. Going forward, more research is needed to understand how technology can be used to foster improved test scores, or if the reliance on test scores are representative of student performance at all.

What is apparent in both case studies is that both principals awakened some of the dormant realities of their students, who were simultaneously navigating through distressed economic and social circumstances. On this point, a Francis Marion high school student shared, “I really didn’t know what I could do for myself until we received an iPad.”

While test scores may not be affected, student engagement within schools can improve. In the 1960s, this type of educational quagmire was understood in the failures of Brown v. Board of Education to create parity within public schools. Facilities were still separate and unequal, despite the legal mandate of desegregation. As a result, low-income and rural poor schools faced the academic repercussions of these inequalities as demonstrated in poor student achievement and growth.

In many ways, schools like Francis Marion and Pendergast are still experiencing the historical effects of being on the wrong side of segregation. Yet, technology access has the potential to enliven the energy of dissatisfied and disassociated teachers, as well as students whose socio-economic status often dictates predictable (or discouraging) life outcomes.

Moving toward an ethos that assesses how technology affects student, parent, and teacher engagement should count for something. The increased inquiry and activity happening within America’s low-income and remote rural schools can be considered progress, especially if more students are enrolling in college or, at least, enhancing their critical thinking and problem-solving skills. Further, measuring increases in student engagement as a corollary to boredom or disengagement should be added to the conversation on school performance. In both case studies, each principal was excited about the potential of technology to change the course of their students’ life trajectories.

Policymakers, state education officials, and educators should start to explore more fully such indices to measure how schools are adapting to the skills necessary for 21st century advancement. Further, educational districts should be calling upon their affiliated schools to explore these opportunities to ensure that parents and other caregivers are provided with the same type of interest and proficiency in new digital skills. As summarized in an old cliché, “it takes a village.”

Conclusion

Getting closer to parity with the time and investments made around technology in schools and communities is one of the primary arguments of this paper. There are benefits to having more robust bridges between where students learn and live in places that ultimately influence their future decisions. The schools in this research have clearly surfaced why technology access is critical for their students as it slowly develops the norms and values for future participation in the new economy. Each case study also demonstrates the importance of making relevant community connections to better prepare households for the burgeoning digital economy so that the tide of progress rises for all and not just the fortunate few.

Nicol Turner Lee is a Fellow at the Brookings Institution, and the author of the forthcoming Brookings Press book, “Digitally Invisible: How the internet is creating the new underclass.”

Special thanks to everyone at Pendergast Elementary and the Francis Marion School, as well as Brookings’s Jack Karsten and Lia Newman for their help with this report.

The Brookings Institution is a nonprofit organization devoted to independent research and policy solutions. Its mission is to conduct high-quality, independent research and, based on that research, to provide innovative, practical recommendations for policymakers and the public. The conclusions and recommendations of any Brookings publication are solely those of its author(s), and do not reflect the views of the Institution, its management, or its other scholars.

Apple, AT&T, Comcast, Google, Microsoft, and Verizon provide general, unrestricted support to the Institution. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions in this report are not influenced by any donation. Brookings recognizes that the value it provides is in its absolute commitment to quality, independence, and impact. Activities supported by its donors reflect this commitment.

-

Footnotes

- Hart, Kim. “The Homework Divide: 12 Million Schoolchildren Lack Internet.” Axios, December 1, 2018. https://www.axios.com/the-homework-gap-kids-without-home-broadband-access-3ad5909f-e2fb-4208-b4d0-574c45ff4fe7.html. This definition differs from the traditional educational reference to achievement gap. It primarily explores students’ access to broadband at home and within the community.

- Each school was visited in August 2019 as part of the research study. Visits were set up after approval from the district superintendents in each community. Field work consisted of data collection through participant observation and direct interviews with administrators, teachers, and community leaders.

- “Testimony of Administrator Irving on The Digital Divide: Bridging the Technological Gap.” National Telecommunications and Information Administration, July 27, 1999, available at https://www.ntia.doc.gov/speechtestimony/1999/testimony-administrator-irving-digital-divide-bridging-technological-gap (last accessed November 18, 2019).

- Monica Anderson et al., “10% of Americans Don’t Use the Internet. Who Are They?,” Pew Research Center (blog), April 22, 2019, available at, https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/04/22/some-americans-dont-use-the-internet-who-are-they/ (last accessed November 18, 2019).

- Colby Leigh Rachfal and Angele A. Gilroy, “Broadband Internet Access and the Digital Divide: Federal Assistance Programs” (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, October 25, 2019), https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/RL30719.pdf.

- Rosenworcel, Jessica. “How to Close the ‘Homework Gap.’” Miami Herald. December 5, 2014. https://www.miamiherald.com/opinion/op-ed/article4300806.html.

- “Fact Sheet: Update Of E-Rate For Broadband In Schools And Libraries,” Federal Communications Commission, July 19, 2013, https://www.fcc.gov/document/fact-sheet-update-e-rate-broadband-schools-and-libraries.

- United States v. Perry County Board of Education, Maury Smith (U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Alabama 1971).

- Cecillia Wang, “How the People of Maricopa County Brought Down ‘America’s Toughest Sheriff,’” blog, American Civil Liberties Union (blog), August 3, 2017, https://www.aclu.org/blog/immigrants-rights/state-and-local-immigration-laws/how-people-maricopa-county-brought-down.

- Before visiting each location, I completed a preliminary asset-mapping of the libraries, community-based organizations, churches, business establishments, and community centers to identify and locate the local resources that can complement the in-school technology programs.

- As part of the project, permissions were secured by district superintendents in each city to interview and observe students on-site. Student information is anonymized for this paper and not reported or attributed to any one individual.

- “State Profiles,” Database, The Nation’s Report Card, 2019, https://www.nationsreportcard.gov/profiles/stateprofile?chort=1&sub=MAT&sj=AL&sfj=NP&st=MN&year=2019R3.

- “Alabama State Department of Education,” Alabama Department of Education, 2019, http://reportcard.alsde.edu/Alsde/OverallScorePage?schoolcode=0000&systemcode=000&year=2019.

- “Francis Marion School,” Alabama Department of Education, 2019, http://reportcard.alsde.edu/Alsde/OverallScorePage?schoolcode=0025&systemcode=053&year=2019.

- BroadbandNow Team, “Report: US States With the Worst and Best Internet Coverage 2018,” August 14, 2018, https://broadbandnow.com/report/us-states-internet-coverage-speed-2018/.

- Aimee A. Howley, Lawrence Wood, and Brian H. Hough, “Rural Elementary School Teachers’ Technology Integration,” Journal of Research in Rural Education 26, no. 9 (2011), http://jrre.psu.edu/articles/26-9.pdf.

- Tandra L. Tyler-Wood, Deborah Cockerham, and Karen R. Johnson, “Implementing New Technologies in a Middle School Curriculum: A Rural Perspective,” Smart Learning Environments 5, no. 1 (October 10, 2018): 22, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40561-018-0073-y.

- Monica Anderson, “Racial and Ethnic Differences in How People Use Mobile Technology,” Pew Research Center FactTank (blog), April 30, 2015, https://pewresearch-org-preprod.go-vip.co/fact-tank/2015/04/30/racial-and-ethnic-differences-in-how-people-use-mobile-technology/.

- John Horrigan, “Connections, Costs and Choices,” Pew Research Center: Internet and Technology (blog), June 17, 2009, https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2009/06/17/connections-costs-and-choices/.

- Daniel O Beltran, Kuntal K Das, and Robert W Fairlie, “Home Computers and Educational Outcomes: Evidence from the NLSY97 and CPS,” International Finance Discussion Papers, no. 958 (November 2018): 47.

- Michelle Alexander, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness (New York: The New Press, 2012).

- Tabassum Rashid and Hanan Muhammad Asghar, “Technology Use, Self-Directed Learning, Student Engagement and Academic Performance: Examining the Interrelations,” Computers in Human Behavior 63 (October 1, 2016): 604–12, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.05.084.

- “Demographics of Mobile Device Ownership and Adoption in the United States,” Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech (blog), June 12, 2019, https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/mobile/.

- Vikki S. Katz, “How Children of Immigrants Use Media to Connect Their Families to the Community,” Journal of Children and Media 4, no. 3 (August 1, 2010): 298–315, https://doi.org/10.1080/17482798.2010.486136.

- Ibid.

- “Does Educational Technology Help Students Learn?” (Reboot Foundation, June 6, 2019), https://reboot-foundation.org/does-educational-technology-help-students-learn/.

- Ibid.

- “Creativity in Learning” (Washington, DC: Gallup, 2019), https://www.gallup.com/education/267449/creativity-learning-transformative-technology-gallup-report-2019.aspx.

- U.S. Census Bureau; 2013-2017 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates, https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=ACS_17_5YR_GCT2801.ST51&prodType=table

- Victoria Rideout and Vikki Katz, “Opportunity for All? Technology and Learning in Lower-Income Families” (The Joan Ganz Cooney Center at Sesame Workshop, February 3, 2016), https://joanganzcooneycenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/jgcc_opportunityforall.pdf.

- Samantha Becker et al., “Opportunity for All: How the American Public Benefits from Internet Access at U.S. Libraries,” Institute of Museum and Library Services, January 3, 2010.

- “Cradlepoint Helps California School District Ensure No Child Is Left Offline” (Cradlepoint, 2016), https://www.cosn.org/sites/default/files/Coachella-Customer-Success-Story.pdf.

- Rideout and Katz, “Opportunity for All?”; Teresa Correa, “Bottom-up Technology Transmission within Families : How Children Influence Their Parents in the Adoption and Use of Digital Media,” December 2012, https://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/handle/2152/22115; Katz, “How Children of Immigrants Use Media to Connect Their Families to the Community.”

- Correa, “Bottom-up Technology Transmission within Families.”

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).