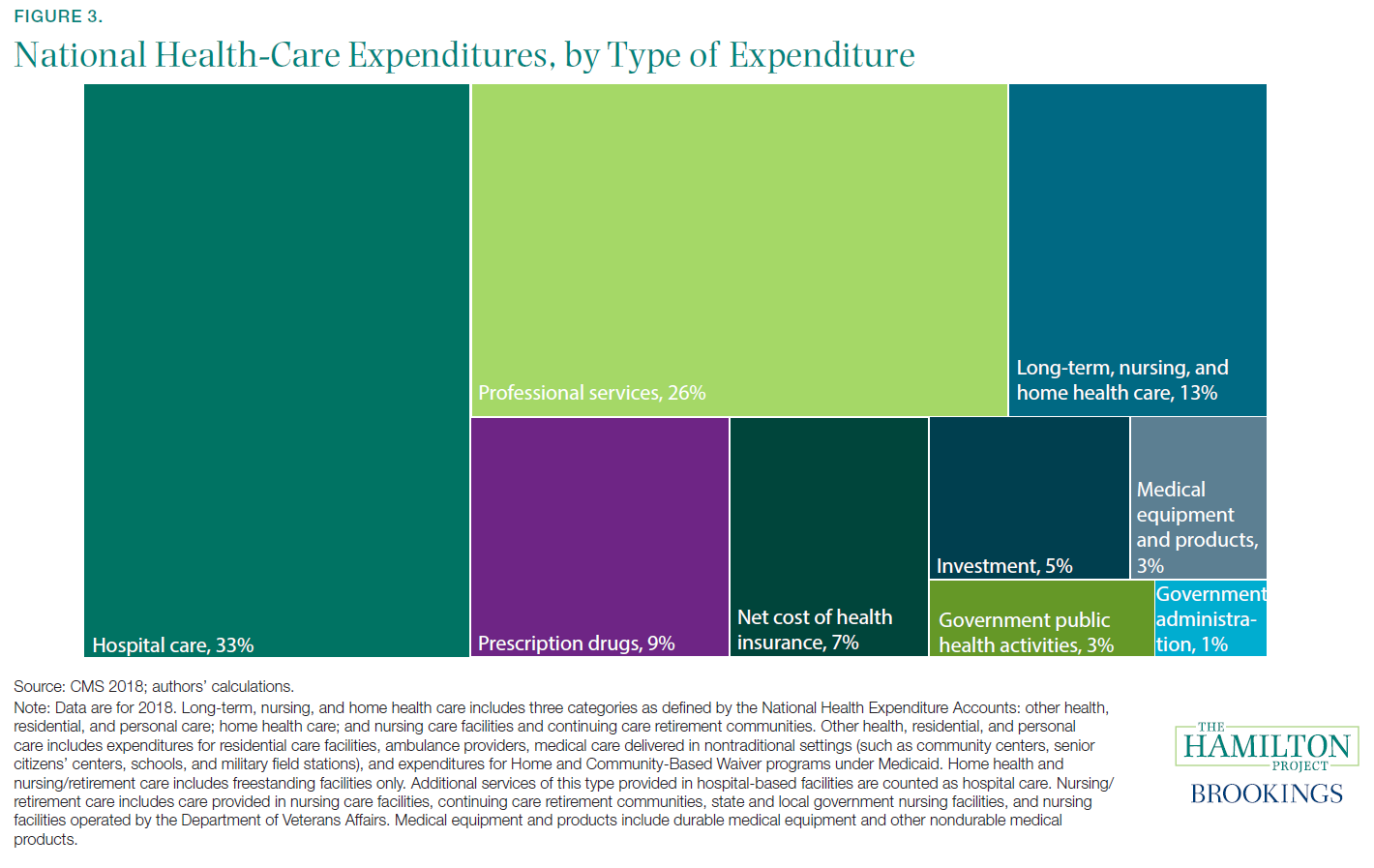

The health-care sector is in many ways the most consequential part of the United States economy. It is a fundamental part of people’s lives, supporting their health and well-being. Moreover, it matters because of its economic size and budgetary implications. The health-care sector now employs 11 percent of American workers (Bureau of Labor Statistics [BLS] 1980–2019b and authors’ calculations) and accounts for 24 percent of government spending (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services [CMS] 1987–2018; Bureau of Economic Analysis 1987–2018; authors’ calculations).[1] Health insurance is the largest component (26 percent) of nonwage compensation (BLS 2019b) and health care is one of the largest categories of consumer spending (8.1 percent of consumer expenditures; BLS 2019a).

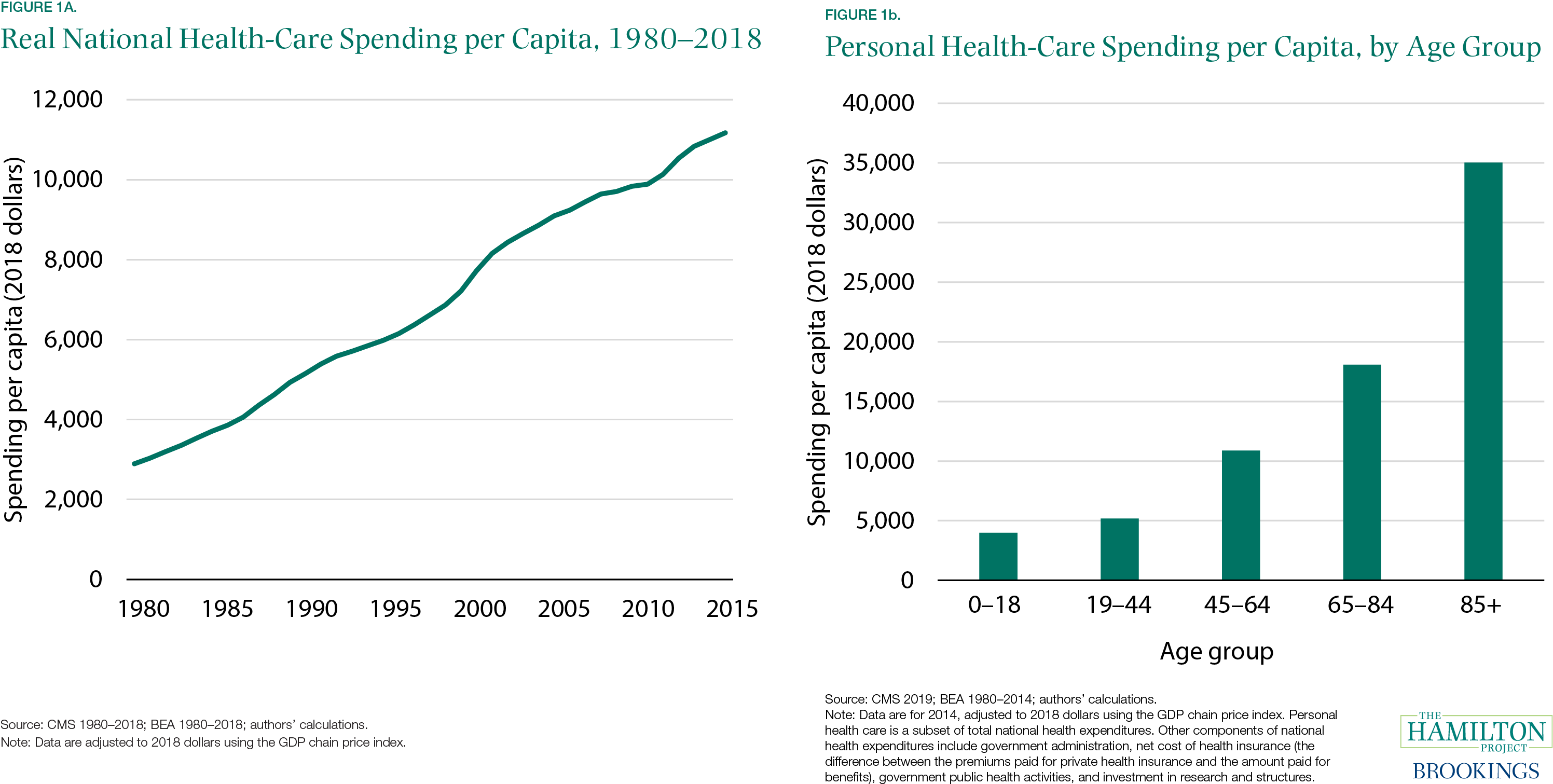

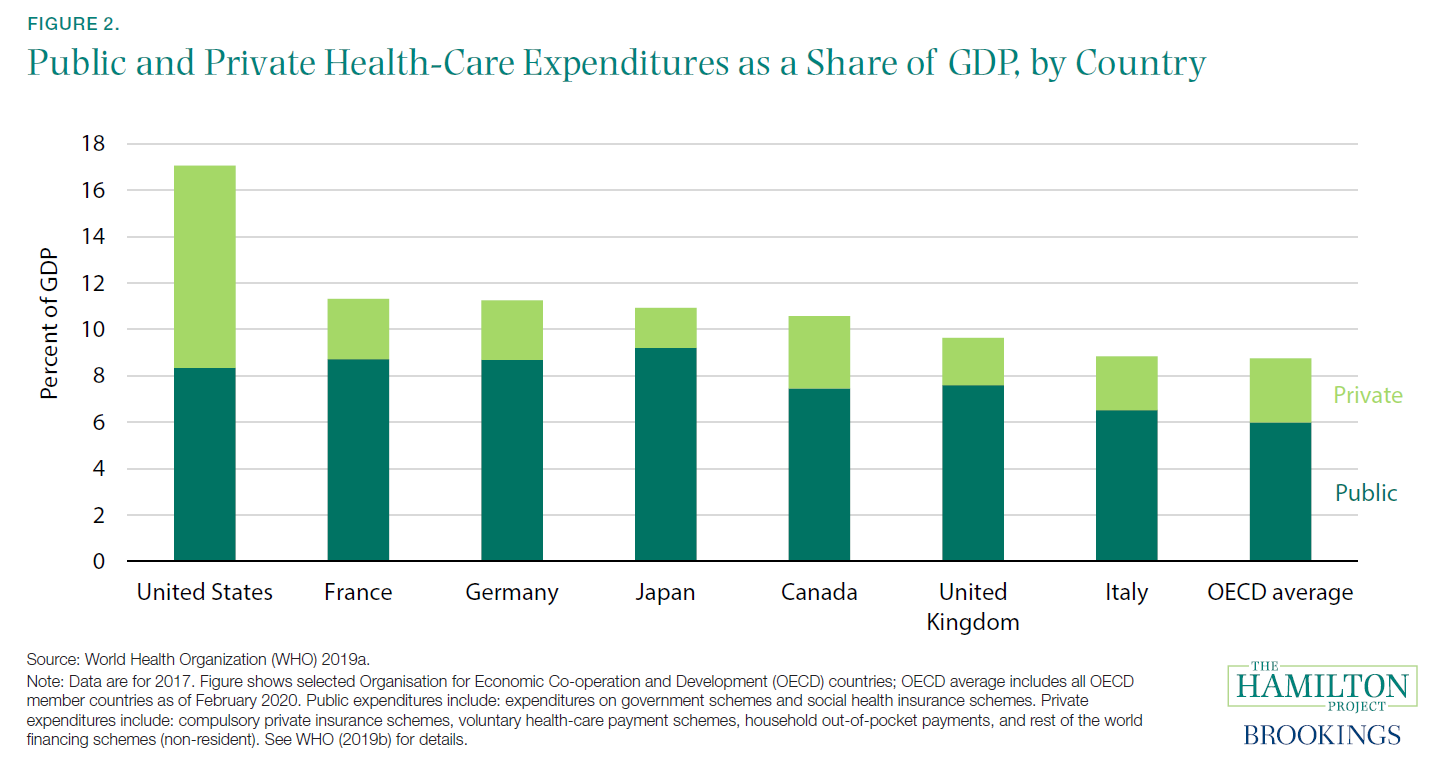

A well-functioning health-care sector is therefore a prerequisite for a well-functioning economy. Unfortunately, the problems with U.S. health care are substantial. The United States spends more than other countries without obtaining better health outcomes (Papanicolas, Woskie, and Jha 2018). Health care is growing as a share of the economy and government budgets in ways that appear unsustainable (CMS 1960–2018; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD] 2015). This growth has slowed at times; health spending as a share of GDP was roughly flat in much of the 1990s, and growth has also slowed to some extent in recent years. But even if expenditures as a share of GDP plateaued at their current level, they would still represent a massive expenditure of resources. Sixty years ago, health care was 5 percent of the U.S. economy, as can be seen in figure A; at 17.7 percent in 2018, it was more than three times that.

This growth represents a range of factors, from new health-care treatments and services to better coverage, higher utilization, and rising prices. Some of these changes are desirable: As a country gets richer, spending a higher share of income on health may be optimal (Hall and Jones 2007).[2] Countries with a higher level of output per capita tend to have a higher level of health expenditures per capita (Sawyer and Cox 2018). In addition, as the population ages, health deteriorates and health-care spending naturally rises. Finally, if productivity advancements are more rapid in tradable goods like agriculture or manufacturing than in services like health care or education, the latter will tend to rise in relative price and as a share of GDP.[3]

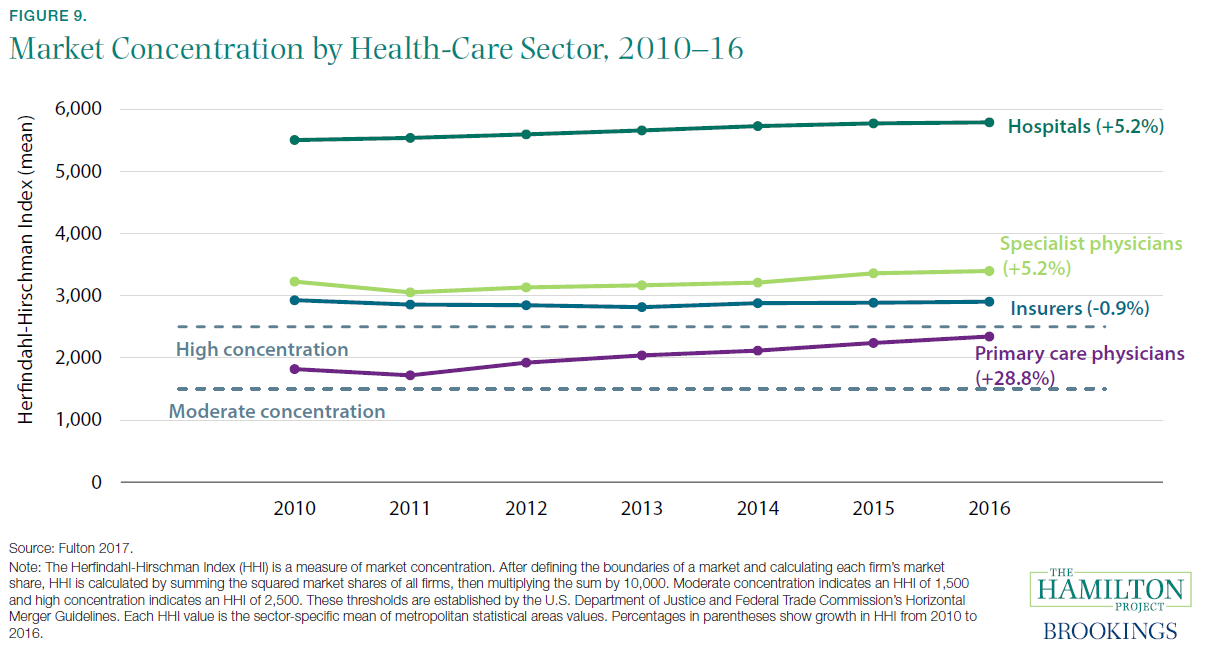

But some of the increase in health-care costs is undesirable (Cutler 2018). Rent-seeking, monopoly power, and other flaws in health-care markets sometimes result in unnecessary care or in elevated health-care prices. In several of the facts that follow, we describe these factors and how they are shaping health care.

Spending by private and public payers have both increased. The United States has a health-care system that largely consists of private providers and private insurance, but as health care has become a larger part of the economy, a higher share of health-care funding has been provided by government (figure B). As of 2018, 34 percent of Americans received their health care via government insurance or direct public provision (Berchick, Barnett, and Upton 2019).

As shown in figure C, health care has doubled as a share of total government expenditures in the last three decades, from 11.9 percent in 1990 to 24.1 percent in 2018. This increase comes from the rising shares of the population enrolled in Medicare, Medicaid, state Children’s Health Insurance Programs, and veterans’ health benefits. Policy changes like the introduction of the Medicare prescription drug benefit (Part D) in 2006 and a major expansion of Medicaid eligibility in 2014 played important roles. At the same time, spending on discretionary programs like education and research and development have decreased as a share of GDP (Congressional Budget Office 2020). If health expenditures continue to increase as a share of government spending, the increase will eventually necessitate either tax increases or reduced spending on other important government functions like public safety, infrastructure, research and development, and education.

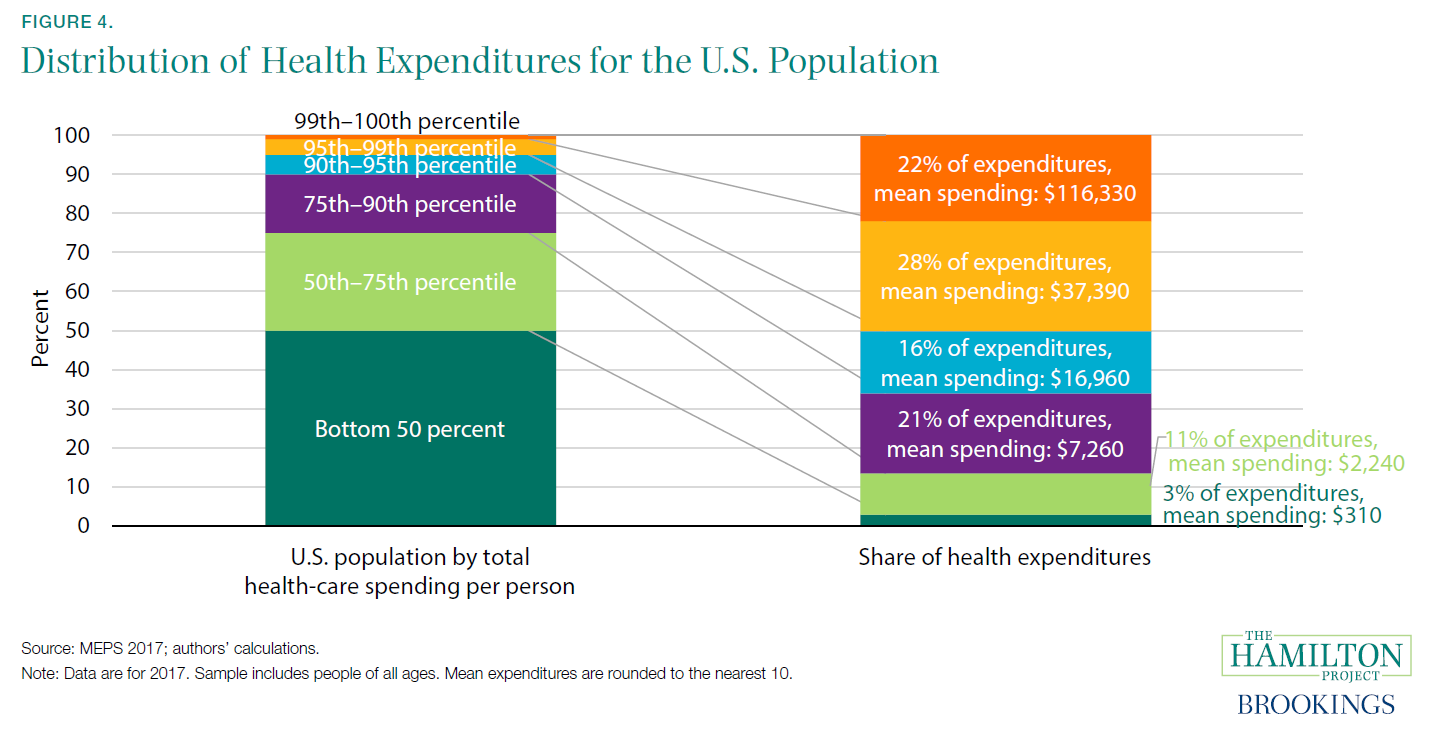

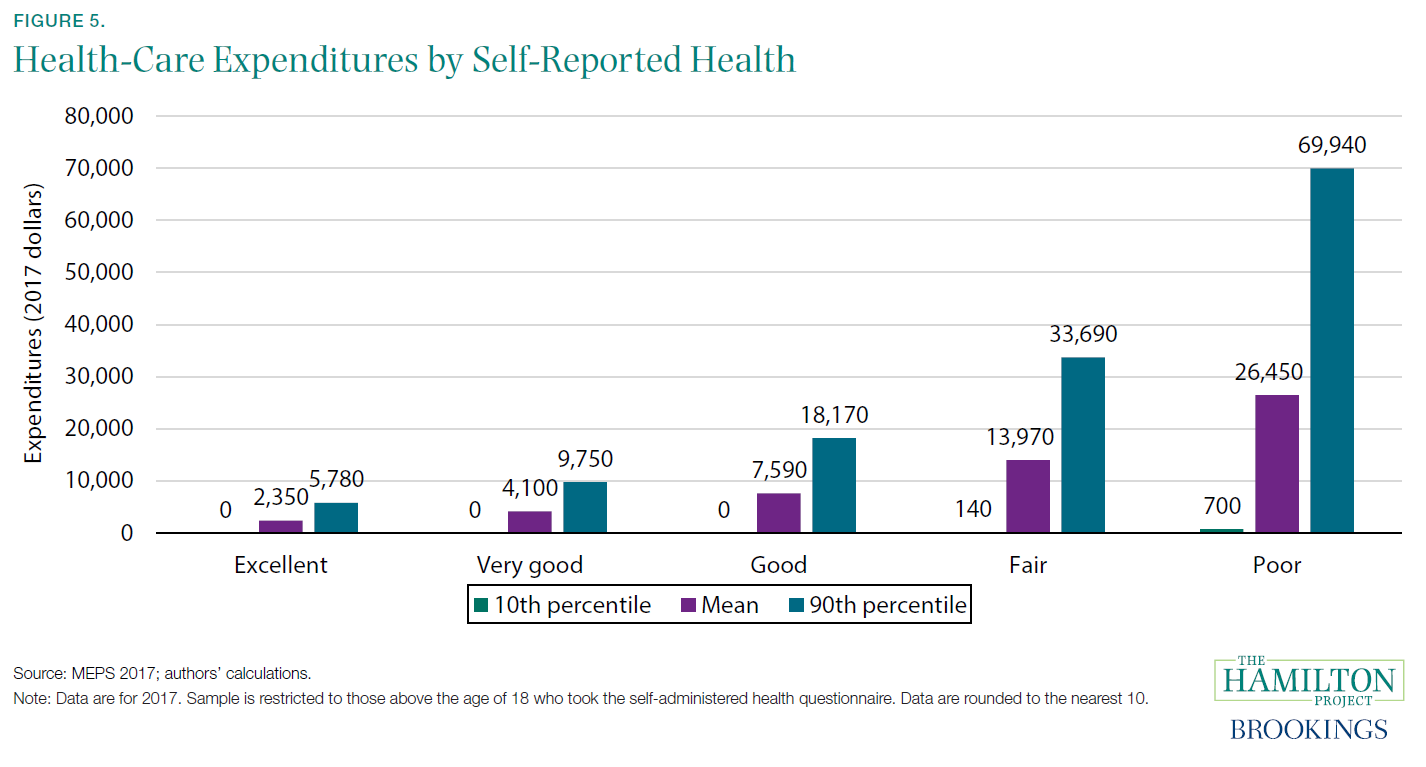

Of course, health costs are also borne by the private sector. Firms and households in the United States spent 10 percent of GDP on health care in 2018. Despite widespread coverage—as of 2018, 91.5 percent of Americans had either private or government health insurance for all or part of the year (Berchick, Barnett, and Upton 2019)—many people still face large and variable out-of-pocket health-care costs. In 2017, more than 1 in 50 Americans who interact with the health-care system have out-of-pocket costs in excess of $5,000, and 1 in 200 have costs over $10,000.[4] At the other end of the distribution, roughly one in seven have no out-of-pocket costs at all in a given year (figure D).[5]

The upper end of the distribution of out-of-pocket costs dwarfs the liquid resources of many U.S. households, meaning that many people faced with a negative health shock may also find themselves in financial trouble. Negative health shocks tend to be associated with loss of income, thereby compounding the problem (Garcia-Gómez et al. 2013). Unexpected health costs can generate bankruptcies and ongoing financial hardship (Gross and Notowidigdo 2011).[6]

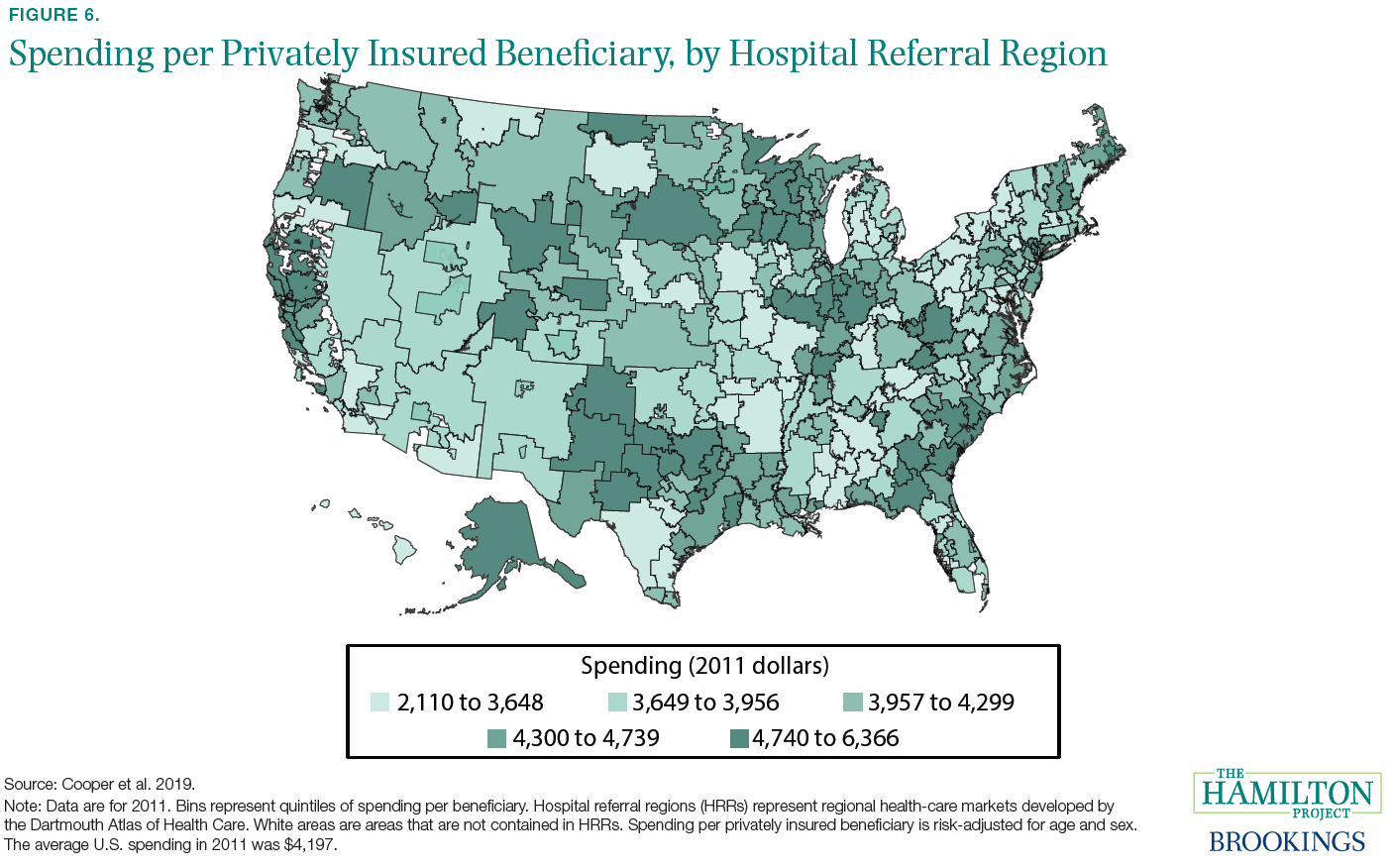

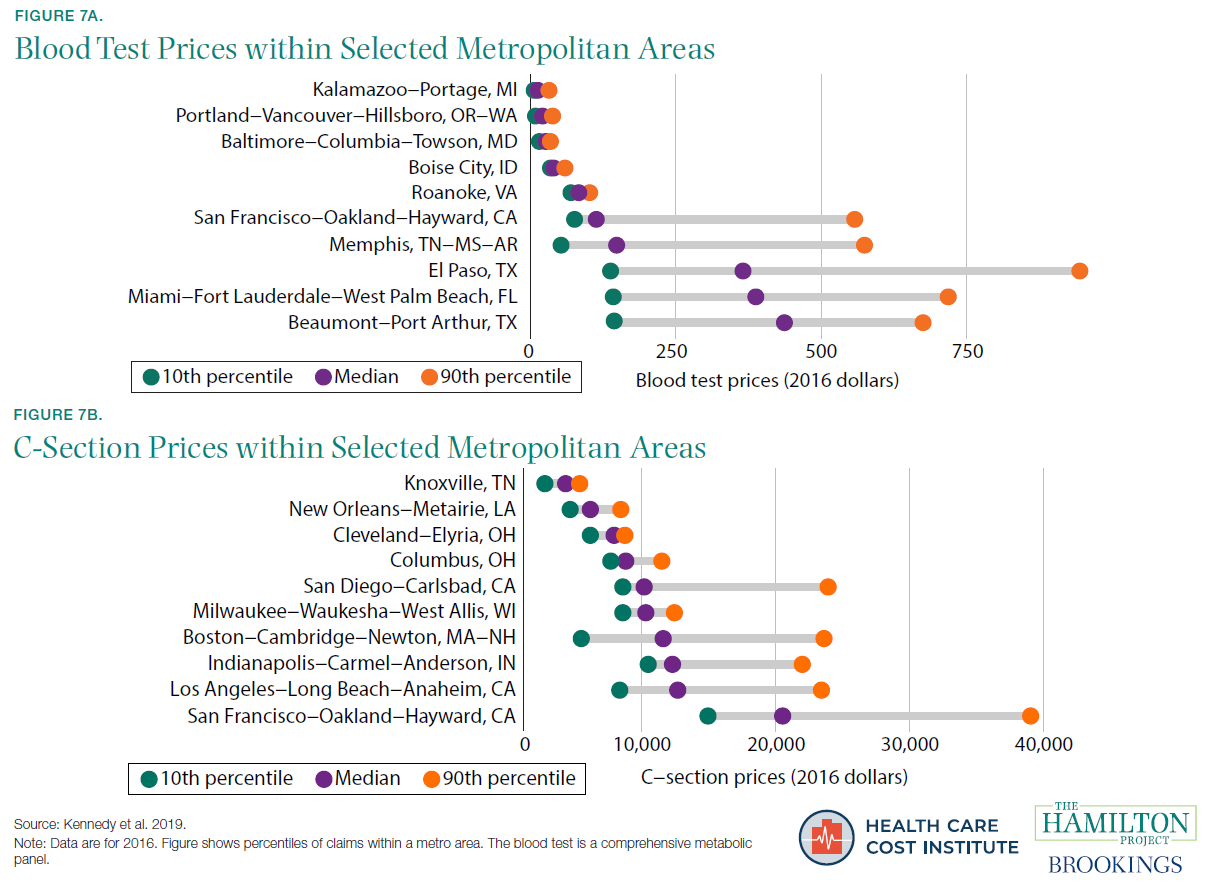

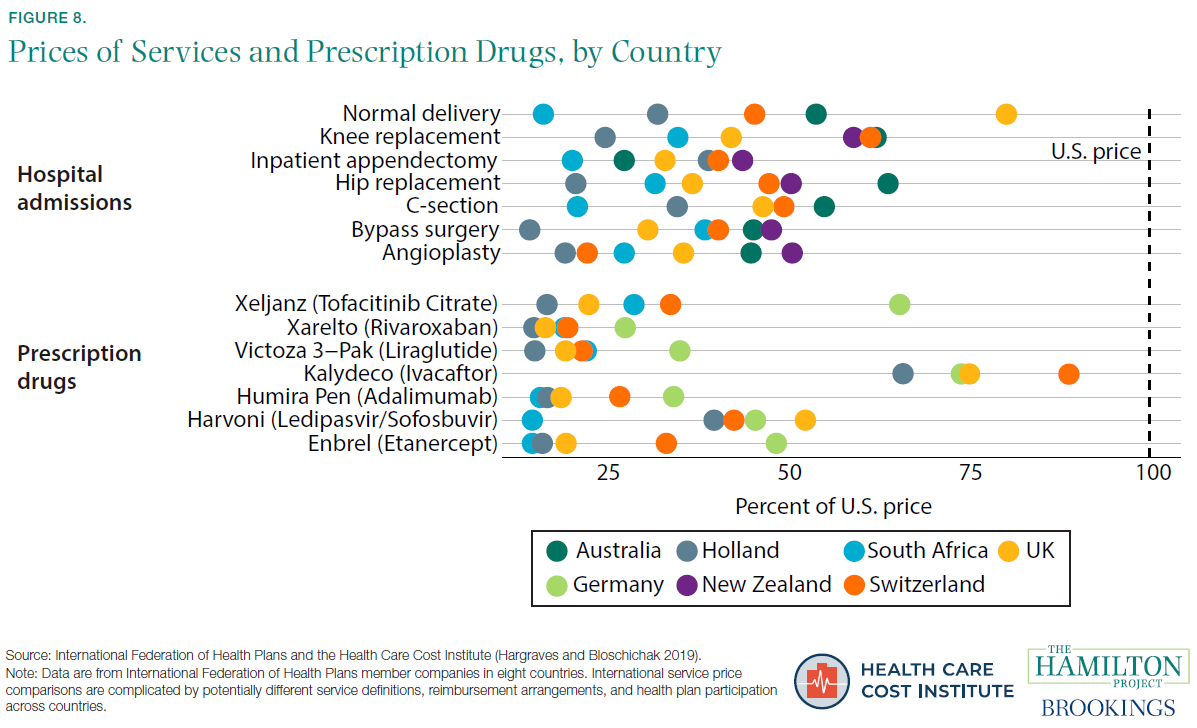

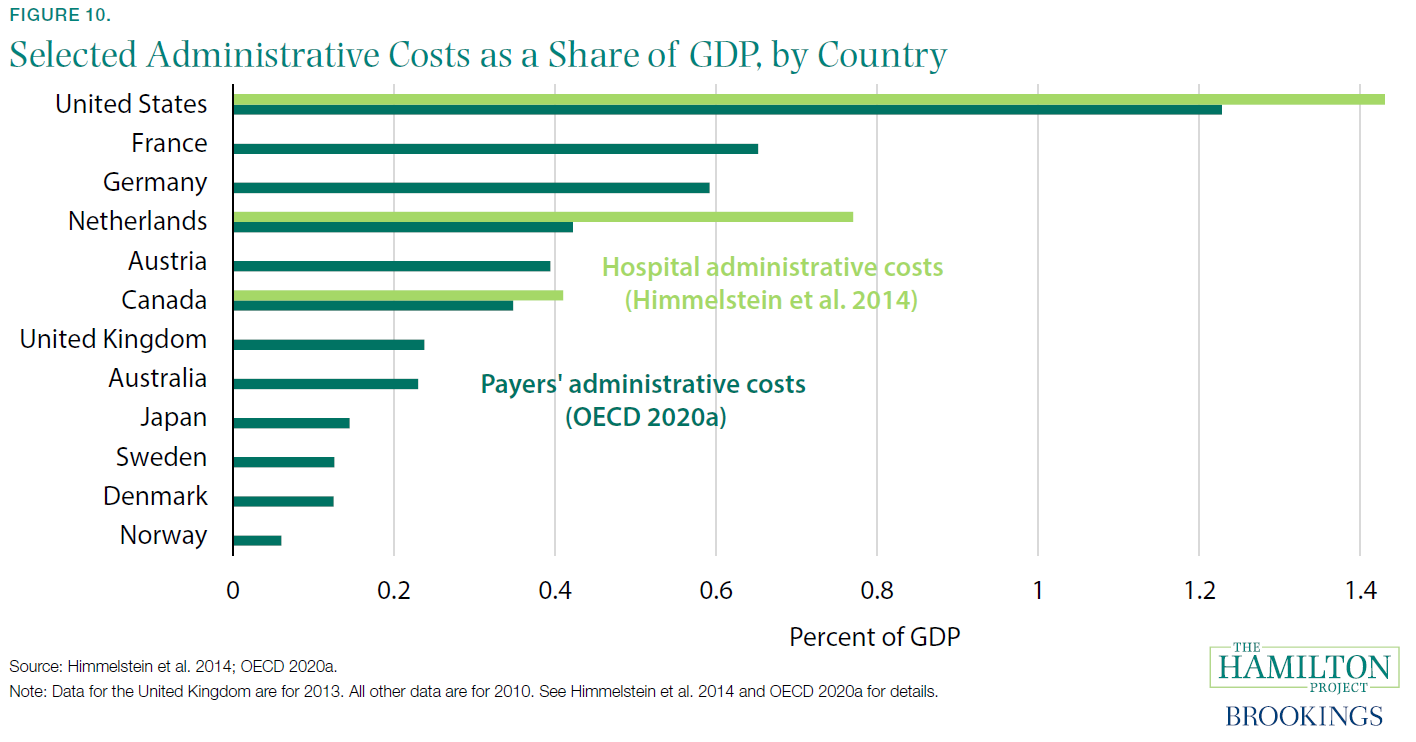

In this document, we provide 12 facts about the economics of U.S. health-care, focusing largely on the private-payer system. We highlight the surge in health-care expenditures and their current high level. We note the wide variation of expenditures across individuals—something that necessitates insurance. We document that the United States pays higher prices than most countries and that these prices vary widely across and within places. We show that a lack of competition and high administrative costs are especially important contributors to high expenditures, indicating the need for reforms to reduce costs in the United States. To keep the focus on these issues, we do not discuss questions of coverage or of how coverage is provided (publicly or via the market), but instead address the questions of why expenditures, costs, and prices are so high.

This analysis aims to promote The Hamilton Project’s mission to support broadly shared economic growth. Removing excess costs from the health-care system is both an economic imperative and a complement to policy efforts to improve health-care access and outcomes. In the following facts we provide context for understanding the landscape of policy options for reducing costs in the health-care system.

Endnotes

[1] The share of health-care employment refers to the share employed by the health-care industry.

[2] However, see Acemoglu, Finkelstein, and Notowidigdo (2013) for a contrasting view. They find that the income elasticity of health care is likely below one.

[3] This dynamic is referred to as Baumol’s cost disease and reflects the need for service-sector wages to keep pace with rising wages in the sectors with high productivity growth.

[4] These calculations use the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS), which excludes long-term care and other components of health-care spending that are included in the national health care expenditure accounts (NHEA) data from Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) used elsewhere in this document. These excluded expenditures could be distributed unevenly across the population and can therefore affect the patterns shown in figures based on MEPS data. For more on a comparison of the types of spending covered in the MEPS and spending covered in the NHEA, which is used in other figures in this document, see Bernard et al. (2012).

[5] High-deductible plans have sometimes been suggested as a way to increase the sensitivity of patients to health-care prices. However, these plans seem to lead patients to reduce their spending indiscriminately, cutting valuable and less-valuable care alike (Brot-Goldberg et al. 2017).>

[6] However, it is important not to overemphasize the role of health expenses in generating bankruptcies; recent research suggests that hospitalizations of uninsured adults generate only about 6 percent of bankruptcies for that group (Dobkin et al. 2018).

[7] Data are for 2014, the most recent year for which spending data by age are available from CMS, and are adjusted to 2018 dollars using the GDP chain price index. These per capita costs are for personal health-care spending, which is a subset of the total spending presented in figure 1a and excludes government administration, net cost of health insurance (the difference between the premiums paid for private health insurance and the amount paid for benefits), government public health activities, and investment in research and structures.

[8] This calculation focuses on the 1980 to 2014 period, rather than 1980 to 2018, due to limited data on spending by age.

[9] This estimate for the United States is slightly lower than that shown in figure A, which is based on data from CMS.

[10] This comparison excludes Italy, which is not included in Papanicolas, Woskie, and Jha (2018).

[11] In the MEPS, which excludes long-term care and other components of health-care spending that are included in the national health care expenditure accounts data from CMS, both out-of-pocket and total spending on prescriptions are roughly 25 percent of total out-of-pocket spending and total expenditures, respectively.

[12] The MEPS excludes long-term care and other components of health-care spending that are included in the national health care expenditure accounts data from CMS used elsewhere in this document. These excluded expenditures are likely distributed unevenly across the population and can therefore affect the patterns shown in figures based on MEPS data. For more on a comparison of the types of spending covered in the MEPS and spending covered in the NHEA, which is used in other figures in this document, see Bernard et al. (2012).

[13] It is not always clear in advance that such care is end-of-life—in other words, the hope is that patients will recover as a result of the care. As such, the amount spent knowingly at the end of life is even lower (Einav et al. 2018).

[14] It is not surprising that the United States has higher prices than poorer countries. The Balassa-Samuelson effect notes that high-income countries have higher prices for non-traded goods and services (like health care) than low-income countries (Balassa 1964; Samuelson 1964). But the Balassa-Samuelson effect does not predict much variation among high-income countries, and yet the United States is clearly at the upper end of the price distribution for health care.

[15]Other studies of international price differences have sometimes found the United States to be less of an outlier, but still high. For example, one survey found that U.S. hospital service prices are only 30 percent higher than the OECD average and just slightly above those of countries like Canada and Austria (Lorenzoni and Koechlin 2017).

[16] Neither of these estimates includes administrative costs to providers. Thus, these calculations embody a different accounting of administrative costs than is cited in Cutler (2020), and the estimated fractions of health-care expenditures are substantially lower.

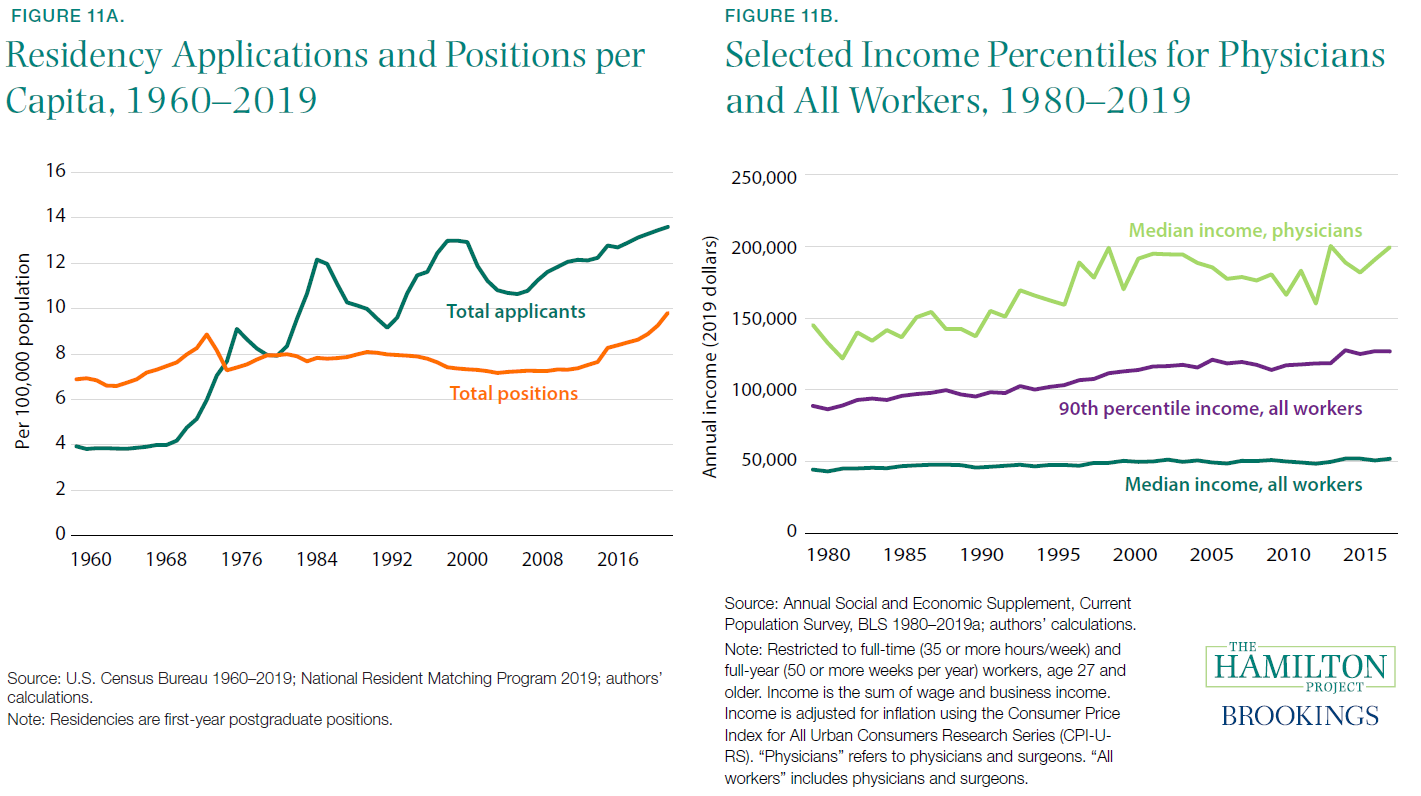

[17] Health-care providers’ share of the labor force refers to health-care occupations.

[18] As described by the American Medical Association, “The number of available first-year (PGY-1) positions rose to 32,194, an increase of 1,962 (6.5 percent) over the prior year. That increase in opportunity reflects the growth in the number of osteopathic programs joining the Main Residency Match as a result of the ongoing transition to a single accreditation system for graduate medical education (GME) programs” (Murphy 2019).

[19] Calculation courtesy of Morris Kleiner.

[20] However, it is less clear what limited health-care labor supply implies for service use, which may diminish when labor supply is restricted.

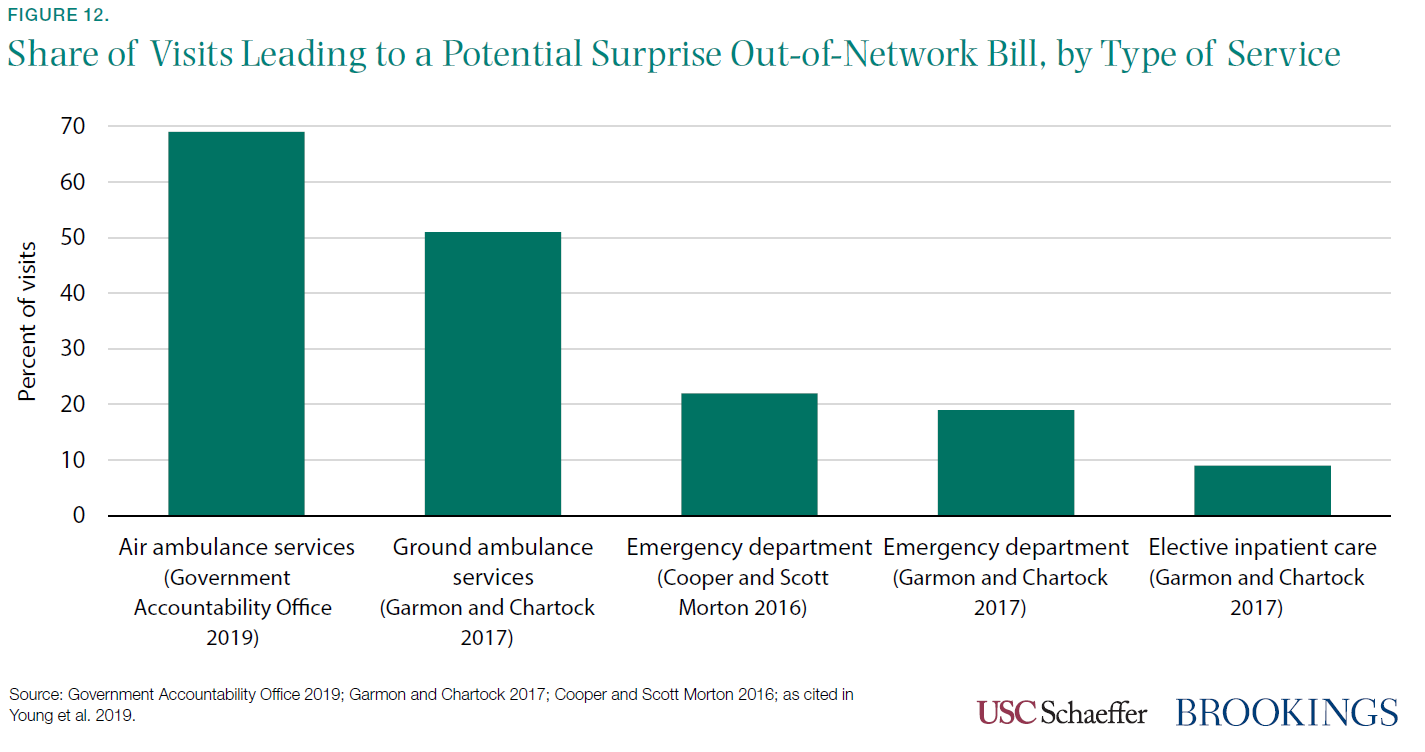

[21] Surprise billing is also more likely when a health plan has no in-network options at a hospital in a particular provider category. In a study of Texas hospitals, between 21 percent and 56 percent of in-network hospitals had no in-network emergency physicians, depending on the health plan (Hall et al. 2016, citing Center for Public Policy Priorities 2014).

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).