The Vitals

Formulating a strategy to deal with China will be an

unavoidable responsibility of the next presidential administration, no matter

who wins the election. In previous campaigns, candidates from both parties have

promised to pursue tougher policies toward China, and there are signs that aggressive

approaches have bipartisan support in Congress, but the level of public support

for an adversarial relationship casts doubt on the likelihood that strategies

for responding to China’s rise will become a major issue in the 2020 election.

-

The disillusionment within the American business community has arguably had the most impact on the politics of China in the United States.

-

While the Trump administration has cast the US-China relationship as a multi-domain strategic competition, the president himself has been more narrowly focused on resetting trade relations and improving the trade balance.

-

Based on Americans’ perceptions of China, it’s unlikely the 2020 presidential election generates an in-depth national conversation on the most effective strategy for responding to China’s rise.

A Closer Look

China has been a salient political issue in each

presidential election dating back to at least the 1992 contest between George

H.W. Bush and Bill Clinton, when, in the shadow of the Tiananmen tragedy, Bill

Clinton promised to get tough on “the butchers of Beijing.” Clinton saw China

as an issue on which to attack Bush, who had prioritized preserving relations

with Beijing over punishing China for its massacre of peaceful protestors. With

the possible exception of

Barack Obama in 2008, presidential candidates of both parties have politicized China

to score points in each successive presidential campaign, by promising to get

tough and secure better terms from the relationship than their predecessors

had, and their challengers would. The 2020 presidential election almost

certainly will continue this trend.

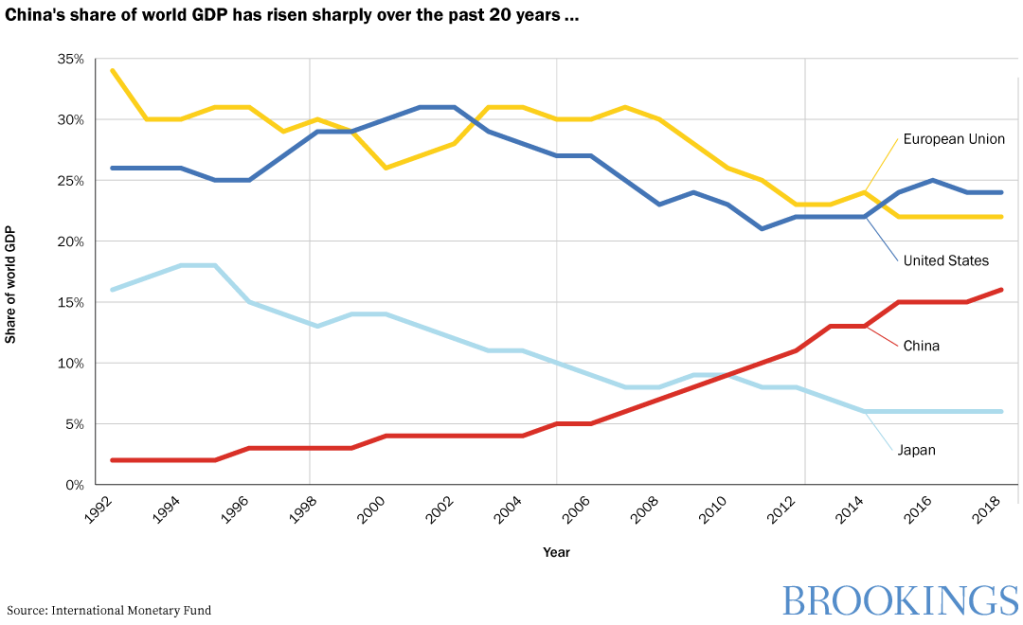

China has grown from an underdeveloped country into America’s foremost economic competitor. Since 1992, China’s share of global GDP has grown from less than 1 percent to 16 percent. During this period, America’s share of global GDP has declined, but only a bit – 26 percent in 1992 to 24 percent in 2017. The big shifts are the declines in Europe’s and Japan’s shares.

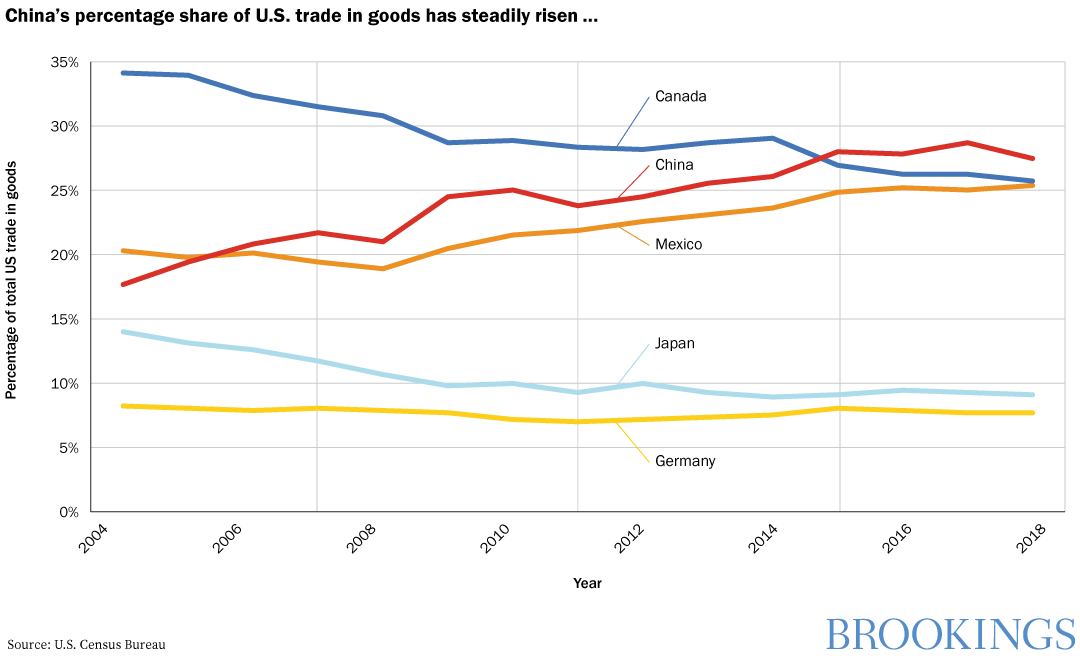

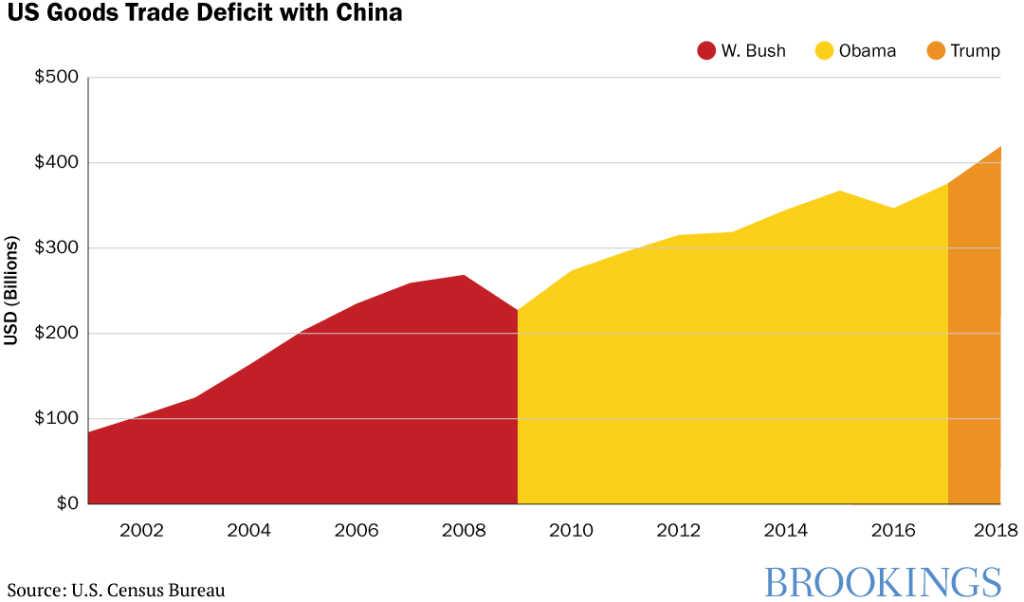

China’s rise in economic power has been accompanied by an

increase in U.S.-China bilateral trade. The United States overall goods and services trade deficit with China in 2018 was $378.6 billion. The U.S. imported

more from China than from any other country in 2018, and China was the third

largest market for U.S. exports. Agricultural goods, aircraft, semiconductors,

and motor vehicles have become leading American goods exports to China, and

computers and electronics are America’s largest goods imports from China.

Since the announcement of his presidential candidacy, Donald

Trump has viewed China as an important element of his political brand. Trump

has demonstrated willingness to shatter old conventions and stake out new

approaches to what he has described as

China’s unfair treatment of the United States. He consistently has portrayed

China as taking advantage of American weakness to grow wealthy and powerful at

America’s expense.

While the Trump administration has cast the relationship as

a multi-domain strategic competition,

President Trump himself has been more narrowly focused. Trump has concentrated

his rhetoric and his personal diplomacy with China’s leaders on resetting trade

relations. Consistent with his views since the 1980s, he has identified the

trade balance as the key measure of fairness in the bilateral relationship. Trump

also has kept pressure up on Beijing to play a helpful – or at a minimum,

non-harmful – role in support of his efforts to denuclearize North Korea.

Meanwhile, there have been indications of growing

bipartisan

political support for a more aggressive

approach toward China, if not necessarily for the tactics the Trump

administration has employed for doing so. Congressional leaders including

Senator Chuck Schumer (D-NY) and Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) have encouraged

efforts to stand up to China. Senators Mark Warner (D-VA) and Marco Rubio

(R-FL) have found common cause in efforts to raise public awareness of threats China

poses to the United States.

Beijing’s actions have had significant bearing on this

political realignment toward China. The country’s leadership seems to have

reversed momentum on economic reform, doused any lingering hopes of political

liberalization, grown indifferent to the deepening concerns of the U.S.

business community, intensified efforts to stifle challenges to government

policy, sought forcefully to assimilate ethnic groups into Chinese society, pursued

greater control over Hong Kong, strained relations with America’s academic and

NGO community, and shown ambitions to displace the United States from its

traditional leadership role in Asia, if not more broadly.

The disillusionment within the American business community arguably has had the most impact on the politics of China

in the United States. In the early 1990s, following the Tiananmen tragedy, the

business community led the call for the Clinton administration to moderate its

approach toward China. At the time, China’s paramount leader, Deng Xiaoping,

was advancing reforms to create a more welcoming environment for foreign firms,

providing an incentive for the U.S. private sector to support deepening ties.

Now, the situation is reversed. Xi Jinping’s economic policies are cementing in

place an uneven playing field for foreign firms to compete against their

Chinese counterparts, causing key voices within the corporate community to

withdraw their advocacy for improving relations. Beijing’s high-profile efforts

to compel American brands to accept China’s positions on sensitive issues such

as Hong Kong and Taiwan have further chilled the U.S. private sector’s

willingness to be perceived as advocating for improved ties, for fear that

doing so could be viewed as shilling for the Chinese Communist Party. Overall, there

is not presently any politically influential constituency within the United

States advocating for strengthening U.S.-China relations.

At the same time, there is not broad public support in the

United States for an adversarial approach toward China. Even as public

attitudes in the United States toward China have grown unfavorable, this trend

has not been matched by public support for seeing China as a danger. According

to a national survey conducted by Chicago Council on Global Affairs, the

American public is evenly split between whether the United States and China are

mostly rivals (49%) or partners (50%). China ranks eighth in a list of twelve

threats in the poll, well behind the threat posed by international terrorism,

North Korea’s nuclear program, and Iran’s nuclear program. Polling by Pew provides similar

results. In that poll, respondents were asked to rate seven threats. China came

in fourth, behind cyber issues, climate change, and Iran. Two-thirds of

respondents in a separate Chicago Council poll have expressed

a preference to deal with the rise of China through friendly cooperation and

engagement, whereas just 30 percent preferred to seek to limit China’s power.

For many Americans, China is not a central concern. So, too,

trade is largely a subset of broader economic perceptions and does not rank

among the highest priority concerns of likely voters. These dynamics will frame

the parameters of political debate around China in the upcoming election.

Barring a new development in greater China that shocks the American public conscience, this suggests the 2020 presidential election most likely will not generate an in-depth national conversation on the most effective strategy for responding to China’s rise. Achieving clarity on this question may be deferred by the vote, but it likely will not be deferred for long. Formulating a strategy to deal with America’s foremost global competitor will be an unavoidable responsibility of the next administration, no matter who prevails.

Research Assistant Kevin Dong provided

assistance with this piece, including on the graphs.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Why has China become such a big political issue?

November 15, 2019