The Vitals

Student debt is a big issue in the 2020 presidential campaign for an obvious reason: There’s a lot of it—about $1.5 trillion, up from $250 billion in 2004. Students loans are now the second largest slice of household debt after mortgages, bigger than credit card debt. About 42 million Americans (about one in every eight) have student loans, so this is a potent issue among voters, particularly younger ones.

-

About 75% of student loan borrowers took loans to go to two- or four-year colleges. Those borrowers account for about half of all outstanding student loan debt.

-

Despite horror stories about college grads with six-figure debt loads, only 6% of borrowers owe more than $100,000.

-

Over the course of a full-time career, the typical U.S. worker with a bachelor’s degree earns nearly $1 million more than a similar worker with just a high school diploma.

A Closer Look

Q. Is college worth the money even if one has to borrow for it? Or is borrowing for college a mistake?

A. It depends. On average, an associate degree or a bachelor’s degree pays off handsomely in the job market; borrowing to earn a degree can make economic sense. Over the course of a career, the typical worker with a bachelor’s degree earns nearly $1 million more than an otherwise similar worker with just a high school diploma if both work fulltime, year-round from age 25. A similar worker with an associate degree earns $360,000 more than a high school grad. And individuals with college degrees experience lower unemployment rates and increased odds of moving up the economic ladder. The payoff is not so great for students who borrow and don’t get a degree or those who pay a lot for a certificate or degree that employers don’t value, a problem that has been particularly acute among for-profit schools. Indeed, the variation in outcomes across colleges and across individual academic programs within a college can be enormous—so students should choose carefully.

Q. Who is doing all this borrowing for college?

A. About 75% of student loan borrowers took loans to go to two- or four-year colleges; they account for about half of all student loan debt outstanding. The remaining 25% of borrowers went to graduate school; they account for the other half of the debt outstanding.

Most undergrads finish college with little or modest debt: About 30% of undergrads graduate with no debt and about 25% with less than $20,000. Despite horror stories about college grads with six-figure debt loads, only 6% of borrowers owe more than $100,000—and they owe about one-third of all the student debt. The government limits federal borrowing by undergrads to $31,000 (for dependent students) and $57,500 (for those no longer dependent on their parents—typically those over age 24). Those who owe more than that almost always have borrowed for graduate school.

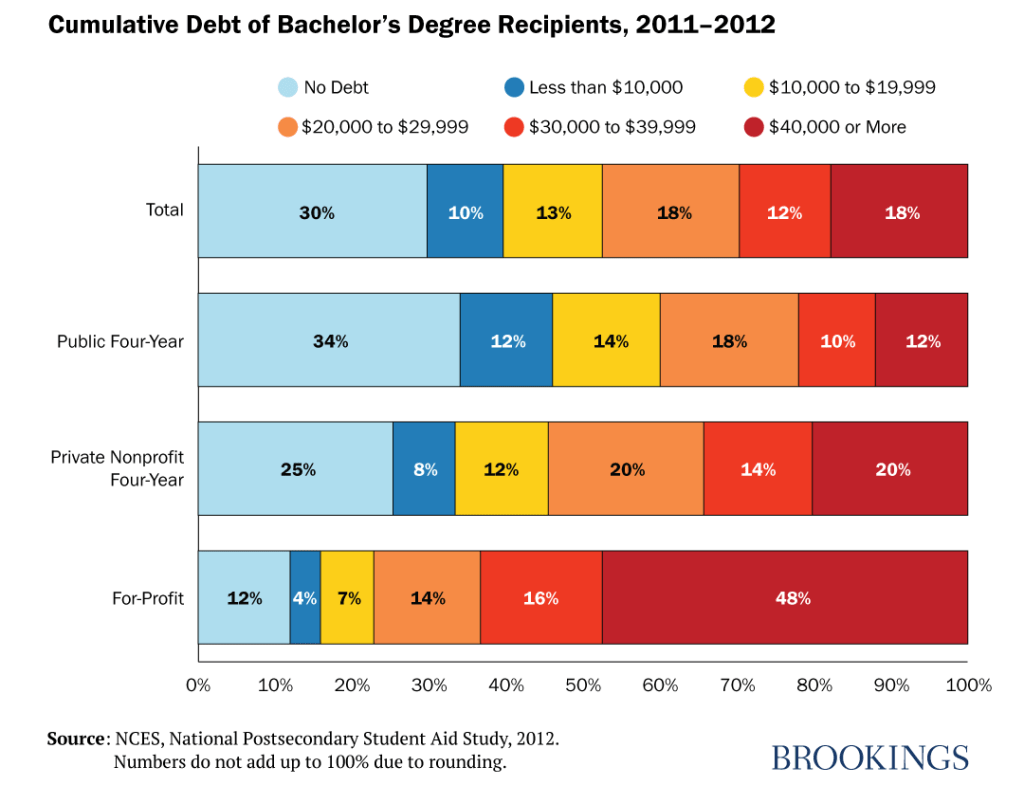

Where one

goes to school makes a big difference. Among public four-year schools, 12% of

bachelor’s degree graduates owe more than $40,000. Among private non-profit

four-year schools, it’s 20%. But among those who went to for-profit schools,

nearly half have loans exceeding $40,000.

Among two-year schools, about two-thirds of community college students (and 59% of those who earn associate degrees) graduate without any debt. Among for-profit schools, only 17% graduate without debt (and 12% of those who earn an associate degree).

Q. Why has student debt increased so much?

- More people are going to college, and more of those who go are from low- and middle-income families.

- Tuition has risen, particularly among four-year public institutions, but rising tuition isn’t as big a factor as well-publicized increases in posted sticker prices; at private four-year colleges, tuition net of scholarships hasn’t risen at all after taking account of scholarships and grants. According to Brad Hershbein of the Upjohn Institute, rising tuition accounts for 62% of the increase in the number of students who borrowed for bachelor’s degrees between 1990 and 2012, and 39% of the increase in the size of the median loan. At community colleges, the average full-time student today receives enough grant aid and federal tax benefits to cover tuition and fees; they do often borrow to cover living expenses.

- The federal government has changed the rules to make loans cheaper and more broadly available. In 1980, Congress allowed parents to borrow. In 1992, Congress eliminated income limits on who can borrow, lifted the ceiling on how much undergrads can borrow, and eliminated the limit on how much parents can borrow. And in 2006, it eliminated the limit on how much grad students can borrow.

- Parents have borrowed more. The average annual borrowing by parents has more than tripled over the last 25 years. As a result, more parents owe very large sums: 8.8% of parent borrowers entering repayment on their last loan in 2014 owed more than $100,000, compared to just 0.4% in 2000.

- Borrowing for graduate school has increased sharply. Between 1994 and 2014, for instance, average annual borrowing by undergrads increased about 75% (to $7,280) while average annual borrowing by grad students rose 110% (to $23,875).

- Borrowing for for-profit schools zoomed as enrollments in higher ed soared during the Great Recession. Between 2000 and 2011, for instance, the number of borrowers leaving for-profit schools nearly quadrupled to over 900,000; the number of borrowers leaving community colleges tripled but totaled less than 500,000.

Q. How many student loan borrowers are in default?

A. The

highest default rates are among students who attended for-profit institutions. The

default

rate within five years of leaving school for undergrads who went to for-profit

schools was 41% for two-year programs and 33% for four-year programs. In

comparison, the default rate at community colleges was 27%; at public four-year

schools, 14%, and at private four-year schools, 13%.

Put differently, out of 100 students who ever attended a for-profit, 23 defaulted within 12 years of starting college in 1996 compared to 43 among those who started in 2004. In contrast, out of 100 students who attended a non-profit school, the number of defaulters rose from 8 to 11 in the same time period. In short, the government has been lending a lot of money to students who went to low-quality programs that they didn’t complete, or that didn’t help them get a well-paying job, or were outright frauds. One obvious solution: Stop lending money to encourage students to attend such schools.

The

penalty for defaulting on a student loan is stiff. The loans generally cannot

be discharged in bankruptcy, and the government can—and does—garnish wages, tax

refunds, and Social Security benefits to get its money back.

Q. Which student loan borrowers are most likely to default?

A. According

to research

by Judy Scott-Clayton of Columbia University, Black graduates with a

bachelor’s degree default at five times the rate of white bachelor’s graduates—21%

compared with 4%. Among all college students who started college in 2003–04 (including

borrowers and non-borrowers), 38% of Black students defaulted within 12 years, compared

to 12% of white students.

Part of

the disparity is because Black students are more likely to attend for-profit

colleges, where almost half of students default within 12 years of college

entry. And Black students borrow more and have lower levels of family income,

wealth, and parental education. Even after accounting for types of schools

attended, family background characteristics, and post-college income, however, there

remains an 11-percentage-point Black–white disparity in default rates.

Q. If so many students are struggling to repay their loans, how much are taxpayers on the hook for?

A. For many years, federal budget forecasters expected the student loan program to earn a profit—until recently. In its latest estimates, the Congressional Budget Office expects the program to cost taxpayers $31 billion for new loans issued over the next decades. And that figure uses an arcane and unrealistic accounting method required by federal law. Using an accounting method that calculates the subsidy to borrowers from getting loans from the government at rates well below those they’d be charged in the private sector, the cost to taxpayers is $307 billion. And that largely excludes the cumulative losses already anticipated on loans issued prior to 2019.

Q. Are student loan burdens economically handicapping an entire generation?

A. More adults between 18 and 35 are living at home, and fewer of them own homes than was the case for their counterparts a decade or two ago. But these trends are mostly due to these folks entering the work force during the Great Recession rather than due to their student loans. Federal Reserve researchers estimate that 20% of the decline in homeownership can be attributed to their increased student loan debt; the bulk of the decline reflects other factors.

Q. What about income-driven repayment plans?

A. Income-driven repayment plans are designed to ease the burden of student loans for those borrowers whose earnings are not high enough to afford payments under the standard plan. Basically, these plans set the monthly loan payment based on family income and size. With most programs in the income-driven repayment plan, monthly payments are 10 or 15% of discretionary income (defined as the amount of income above what’s needed to cover taxes and living expenses, usually 150% of the poverty line), but never more than you would pay with the standard 10-year repayment plan. Unlike the standard repayment plan, any outstanding balances in the income-driven repayment plans are forgiven after 20 or 25 years of payment. There are currently 8.1 million borrowers enrolled in one of the government’s four income-driven plans. Even admirers of the income-driven repayment approach say the current approach in the U.S. is too complicated to work well, and there is substantial criticism of the way the government and the loan servicing outfit it has hired have administered a program established in 2007 to forgive loans for students who took public service jobs. Still, many experts see an improved version of income-driven repayment schemes as a promising approach for the future.

Q. What’s with all these proposals to forgive student debt?

A. Some Democratic candidates are proposing to forgive all (Bernie Sanders) or some student debt. Sen. Elizabeth Warren, for instance, proposes to forgive up to $50,000 in loans for households with less than $100,000 in annual income. Borrowers with incomes between $100,000 and $250,000 would get less relief, and those with incomes above $250,000 would get none. She says this would wipe out student loan debt altogether for more than 75% of Americans with outstanding student loans. Former Vice President Joe Biden would enroll everyone in income-related payment plans (though anyone could opt out). Those making $25,000 or less wouldn’t make any payments and interest on their loans wouldn’t accrue. Others would pay 5% of their discretionary income over $25,000 toward their loan. After 20 years, any unpaid balance would be forgiven. Pete Buttigieg favors expansion of some existing loan forgiveness programs, but not widespread debt cancellation.

Forgiving

student loans would, obviously, be a boon to those who owe money—and would

certainly give them money to spend on other things.

But whose

loans should be forgiven? “What we have in place and we need to improve is a

system that says, ‘If you cannot afford your loan payments, we will forgive

them’,” Sandra Baum, a student loan scholar at the Urban Institute, said at a

forum at the Hutchins Center at Brookings in October 2019. “The

question of whether we should also have a program that says, ‘Let’s also

forgive the loan payments even if you can afford them’ is another question.”

Despite her best intentions and her description of her plan as “progressive,” in fact, the bulk of the benefits from Sen. Warren’s proposal would go to the top 40% of households because they have the bulk of the loans. Borrowers with advanced degrees represent 27% of borrowers, and would get 37% of the benefit.

Loan forgiveness proposals also raise questions of fairness: Is forgiving all or some outstanding loans fair to those who worked hard to pay off their debts? Is it fair to taxpayers who did not attend college?

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Who owes all that student debt? And who’d benefit if it were forgiven?

January 28, 2020