The Vitals

Many

Democratic presidential candidates would raise taxes on the wealthiest Americans

to reduce inequality, fund programs benefitting lower income households, and mitigate

the amount of dynastic wealth in the U.S. However, those who disagree with

these proposals argue they will have negative consequences, including less investment,

slower economic growth, and more creative tax avoidance.

-

The Congressional Budget Office estimates that the best-off 1 percent of American households saw their income before taxes nearly triple between 1979 and 2016.

-

The Federal Reserve estimates that the top 1 percent of Americans hold slightly more wealth than entire the bottom 90 percent, and their share has been rising over time.

-

Under current law, only two out of every 1,000 people who die are wealthy enough to trigger the estate tax – or about 1,900 estates in 2018.

Watch

A Closer Look

Several Democratic presidential candidates propose to raise taxes on the rich to raise money both to pay for their spending agenda and to reduce income inequality. They argue that the people who have benefited the most in recent years should bear the burden of the cost of programs that help the rest of the population. In light of the widening gap between economic winners and losers, they would use the tax code to reduce inequality more aggressively than today’s tax code does, and they devote some of the revenues to fund programs that benefit less well-off Americans. They also point out that the average tax rate paid by people at the top has fallen. Opponents say the rich already pay at least their fair share of federal taxes, and warn that raising taxes will have unwelcome side effects on the economy such as less investment and slower economic growth.

What do we mean when we talk about rich Americans? There are the well-off: About 9% of the households in the U.S. have income greater than $200,000, and they get almost 45% of all pre-tax income, according to the Tax Policy Center. And then there are the really rich: the top 0.4% of households—about 700,000 in all—have incomes above $1 million a year and get 13% of all pre-tax income. Since the 1980s, those at the very top have enjoyed faster growing incomes than the rest of the America. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that the best-off 1% of American households (average annual income $1.8 million in 2016) saw their inflation-adjust incomes before taxes nearly triple between 1979 and 2016; the next best-off 9% saw theirs grow by 75% while everyone else saw their pre-tax incomes rise by 33%.

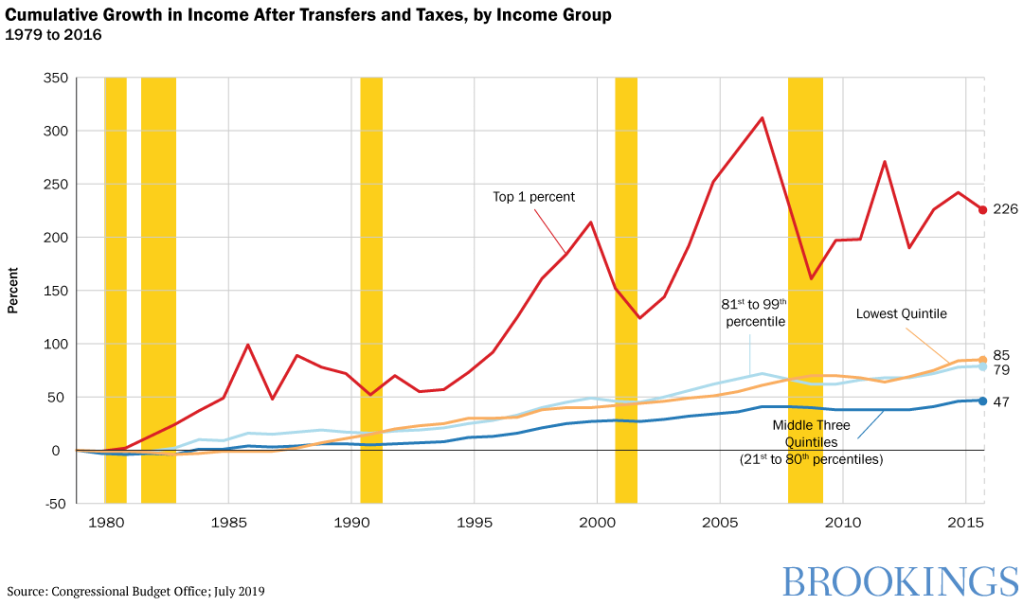

The rich generally pay more of their incomes in taxes than the rest of us. The top fifth of households got 54% of all income and paid 69% of federal taxes; the top 1% got 16% of the income and paid 25% of all federal taxes, according to the CBO. Some people argue that inequality is not as bad as some accounts suggest because they don’t take into account “transfer payments”—government benefits such as Social Security, food stamps, and the like—that are designed to help lower-income folks more than upper-income folks. Still, as the chart here shows, even after accounting for all federal tax and benefit programs, incomes of the top 20% rose faster than those of the rest of the population. And the after-tax-and-transfers income of the top 1% rose by 226% between 1979 and 2016, nearly five times faster than the incomes of people in the middle of the income distribution.

So if we wanted to raise taxes on the rich, how might we do it? Here are brief descriptions of a few of the proposals being discussed in the 2020 campaign:

Increase income tax rates at the top

Couples

with taxable incomes (that is, after deductions) of $612,000 or more currently face

a 37% tax rate on each additional dollar of income; those with incomes between $408,000

and $612,000 face a 35% marginal tax rate. In the several decades, that top marginal

tax rate has fallen from 50% in 1986 to 28% in 1988 and risen as high as 39.6% just

a couple of years ago. Democratic candidates often propose undoing the 2017 Tax

Cuts and Jobs Act or otherwise raising the income tax rate on the best-off Americans.

Raising the tax rate by one percentage point on the top two brackets would raise

about $125 billion over 10 years, according to the Congressional Budget Office. Some Democrats

talk of raising the top tax rate as high as 70%.

Advocates

of raising the tax rates by one point see it as an administratively simple act that

the top earners in the U.S. wouldn’t really feel that much, and that would result

in a more progressive—and revenue-producing—tax code than we have today.

Opponents of raising the tax rates

hold that higher

tax rates can reduce the affected taxpayers’ incentive to work and save. They also

can encourage taxpayers to shift income from taxable to nontaxable or tax-deferred

forms (by substituting tax-exempt municipal bonds for other investments, for example,

or by opting for more tax-exempt fringe benefits instead of cash compensation).

Impose a tax on wealth

Income

is different from wealth. Income is what you earn from your labor each year as well

as interest, dividends, capital gains, and rents (if you’re lucky enough to have

any). Wealth is the value of the things you own, such as stocks, bonds, houses,

etc. The federal government taxes income, but generally doesn’t tax wealth except

when someone makes a profit on the sale of assets, such as a share of stock or a

piece of property. The Federal Reserve estimates

that the top 1% holds slightly more wealth (31.1%) than entire the bottom 90% of

the population (29.9%), and their share has rising been over time.

Senator Elizabeth Warren’s proposal would impose a 2% annual tax on

households with a net worth of more than $50 million, and a 3% tax on every dollar

of net worth over $1 billion. A family worth $60 million, for instance, would owe

$200,000 in wealth tax on top of their income taxes. The developers of this tax,

Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman of the University of California at Berkeley, estimate

that 75,000 households—or about one out of 1,700—would pay the tax.

Advocates

say a wealth tax would dilute the largest fortunes in the U.S. and restrain the

emergence of a plutocracy. It could encourage the wealthy to dissipate their fortunes

by spending the money, giving it to charity, or giving it to their children to avoid

the tax. But even so it would still raise a lot of money. Saez and Zucman say Warren’s

tax would yield $2.75 trillion over 10 years. Critics, including former Treasury

Secretary Larry Summers, say that’s a substantial overestimate.

Opponents say that a wealth tax could discourage or penalize the most successful entrepreneurs, not just old money. And they say these sorts of taxes are hard to administer—the IRS would have to value art collections and antiques, for instance—and would spur creative tax avoidance. In 1990, a dozen countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development had wealth taxes. Today, only three do—Norway, Spain and Switzerland. Opponents also note that wealth taxes often don’t meet the redistributive goals their proponents envision, drawing on a 2018 OECD report.

Increase the estate tax

The estate tax is levied on the assets of the very best-off Americans when they die. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act increased the level at which the federal estate tax kicks in so that the tax—at a rate of 40%—applies only to estates over $11.2 million. Only two of every 1,000 people are wealthy enough to trigger the tax when they die, or about 1,900 estates in 2018, according to the Tax Policy Center. Only 80 small farms and small businesses (defined as estates with farm or business assets of more than $5 million that make up at least half of the estate) paid the estate tax in 2017, again according to the Tax Policy Center. Estate and (related) gift taxes brought the government about $19 billion in 2019, only 0.5% of all federal revenues.

One proposal would lower the threshold to estates worth $3.5 million

(where it used to be) and impose graduated taxes depending on the size of the estate

from 45% up to 65%. It would raise more than $300 billion over 10 years. Advocates

of an estate tax hold that it is a good way to avoid dynastic wealth in the U.S.

and make the U.S. a fairer place where merit matters more and the net worth of one’s

parents matters less. As the wealthy get wealthier, they say, a stronger estate

tax is increasingly important.

Opponents argue that the truly wealthy find ways

to avoid the estate tax with high-priced lawyers and accountants before they

die, and that the tax is simply unfair to those who want to pass along their hard-earned

assets onto children—such as successful small business owners or independent investors,

for instance. A tough estate tax can penalize people who invest in high risk, high-reward

ventures that produce innovation and prosperity.

When someone dies with stocks, property or other assets that are worth more than he or she paid for them, the heirs do not have to pay capital gains taxes on those profits. No one does; the profits go completely untaxed. (In the tax world, this is known as “a step-up in basis”) Former Vice President Joe Biden, among others, has proposed taxing these profits. Heirs would have to pay tax when they sell the assets they inherit.

Lift the Social Security payroll tax cap

Social Security is financed by a 12.4% tax

on wages, split evenly between employers and employees. This payroll tax applies

to wages up to $132,900 in 2019. When Social Security began in the 1930s, about

92% of earnings from jobs covered by the program were taxed—but as wages have grown,

the cap hasn’t kept up, so today about 83% of earnings are hit by the Social Security

payroll tax.

One option is to raise the ceiling to $285,000

and adjust it annually so 90% of earnings are taxed, with an increase in the Social

Security benefits these workers get in retirement. According to the Congressional

Budget Office, this would raise $805 billion over 10 years. Advocates

of lifting the cap say it will shore up Social Security finances so it can continue

to pay all promised benefits beyond 2034, the year that Social

Security trustees say the trust fund will run dry. Advocates also point

to the fact that it would only affect higher-paid workers.

Opponents say this would cut cash wages

to the affected workers—the more taxes an employer pays the less it will be willing

to pay in cash wages, economists say. It also reduces higher-income Americans’ incentive

to work while increasing incentives for employers to provide more untaxed benefits

instead of cash wages.

Commentary

Who are the rich and how might we tax them more?

October 15, 2019