The Vitals

President Trump has advocated for greater trade protectionism and imposed a series of tariffs on China, Mexico, Canada, the European Union, and other trading partners. His administration justified these policies on three grounds: that they would benefit American workers, especially in manufacturing; that they would give the United States leverage to renegotiate trade agreements with other countries; and that they were necessary to protect American national security. Judged by these three metrics, how successful were Trump’s tariffs? And what’s at stake in this election for the future of American trade policy?

-

American firms and consumers paid the vast majority of the cost of Trump’s tariffs.

-

While tariffs benefited some workers in import-competing industries, they hurt workers in sectors that rely on imported inputs and those in exporting industries facing retaliation from trade partners.

-

Trump’s tariffs did not help the U.S. negotiate better trade agreements or significantly improve national security.

A closer look

What are tariffs?

Tariffs are taxes paid on imported goods. In earlier eras tariffs were an important source of government revenue, but in recent decades the U.S. government has used tariffs primarily to shield certain industries from foreign competition. Over the years, Congress has delegated substantial authority to impose tariffs to the executive branch, which means presidents have considerable discretion to increase tariffs on specific products or imports from specific countries.

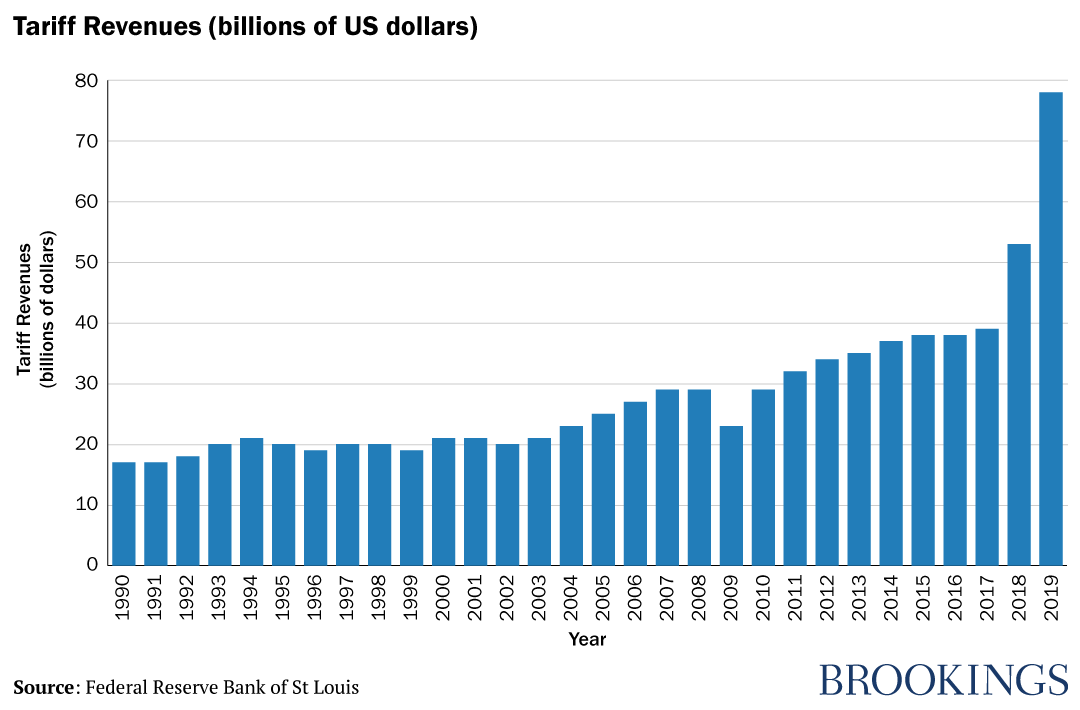

President Trump used this power to increase tariffs on solar panels, washing machines, steel, and aluminum, as well as on a broad range of products from China. Overall, in 2019, the U.S. government brought in $79 billion in tariffs, twice the value from two years earlier and a sharp break from recent trends.

Who pays for tariffs?

The $79 billion brought in by the Treasury could in principle come from three different sources: the foreign companies exporting goods to the United States; the American companies importing goods from abroad, or using imported inputs in their production processes; and American households as final consumers. Tracking precisely who pays for tariffs is difficult, because it depends on how buyers and sellers adjust their prices in response to tariffs, and how these price changes then ripple though supply chains and down to final consumers. The Trump administration has repeatedly argued that foreign companies are paying for tariffs. But multiple studies suggest this is not the case: the cost of tariffs have been borne almost entirely by American households and American firms, not foreign exporters. While estimates vary, economic analyses suggest the average American household has paid somewhere from several hundred up to a thousand dollars or more per year thanks to higher consumer prices attributable to the tariffs.

Did tariffs benefit American workers?

It depends which workers we’re talking about. Workers who produce the specific goods covered by tariffs typically benefit from the protection. While it is difficult to pin down exact numbers, the tariffs on steel products appear to have helped create several thousand jobs in the steel industry; similarly, tariffs on washing machines are associated with approximately 1,800 new jobs at Whirlpool, Samsung, and LG factories in the US. In these specific industries, then, tariffs have probably been good for workers.

But any benefits for workers in import-competing industries need to be balanced against losses for two other groups of workers. First, many workers are employed in factories that use imported goods as inputs in their production processes, and when these imports increase in cost due to tariffs, it harms their production, often leading to job losses. Second, when the U.S. unilaterally imposes tariffs, American trading partners often implement retaliatory tariffs which may limit U.S. export production, again ultimately harming workers in these industries.

In general, then, Trump’s tariffs have helped some workers and hurt others. Nothing is particularly surprising about this; trade policy almost always has important distributive effects, and any change in trade policy is a choice to benefit some groups at the expense of others. Yet, overall, when economists have attempted to add up the net effect of Trump’s tariffs on jobs, any gains in importing-competing sectors appear to have been more than offset by losses in industries that use imported inputs and face retaliation on their foreign exports. And even those jobs that have been created have come at great cost: studies suggest American consumers paid about $817,000 in higher prices attributable to the tariffs for every job created in the washing machine industry and $900,000 in the steel industry. While policy interventions to support manufacturing jobs may be warranted, there are cheaper ways to do so.

Did tariffs help the US negotiate better trade agreements?

The Trump administration also argued tariffs were part of a tougher negotiating posture that would give the United States leverage to secure more favorable trade agreements. During its first term the administration completed two major trade agreements: the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), which updated the previous North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA); and the so-called “Phase One” China deal. U.S. tariffs certainly shaped the context for both the USMCA and China negotiations: in the absence of U.S. pressure, including the application of tariffs and threats of future tariffs, it seems unlikely either Mexico and Canada or China would have sought to negotiate a new deal with the Trump administration. In this basic sense, then, Trump’s tariffs did give the U.S. trade negotiators some leverage.

Yet when we look in closer detail at the outcome of these negotiations, the threat of tariffs does not appear to have brought substantial gains to the U.S. The USMCA is, in general, very similar to NAFTA. And the Phase One trade deal consisted mostly of basic purchase agreements—which, due in part to the COVID-19 shutdown, are extremely unlikely to be attained—while punting the trickier, but more important, structural questions to a hypothetical Phase Two deal (which at this point seems unlikely to ever occur). Tariffs may get other countries’ attention, but don’t necessarily lead them to make substantial concessions to U.S. demands.

And while Trump’s tariffs may have brought some countries to the negotiating table, in the long run the tariffs likely also contributed to pushing other potential trade partners away. When negotiating trade agreements, countries want partners whose policies are stable and predictable, with the goal of establishing a long-term, win-win partnership. Trump’s eagerness to resort to tariffs, including in relations with close allies, has made the U.S. a less desirable trade partner for other countries.

Did tariffs improve American national security?

More than any other recent administration, President Trump has cited national security concerns as a justification for protectionist trade policies. His administration imposed tariffs on steel and aluminum imports on the basis of national security reviews (known as Section 232 investigations), and threatened to do so for automobiles, uranium, and titanium. The administration has framed its China trade policy in national security terms, particularly with respect to technology competition involving companies such as Huawei and TikTok. White House advisor Peter Navarro has argued “economic security is national security,” and sought to explicitly link a more confrontational and assertive international economic policy with a more aggressive military and foreign policy.

Evaluating the impact of trade policy on national security is difficult. Overall, there is a general consensus among Washington policymakers that America’s heightened security competition with China merits revising the economic strategy of the 1990s and 2000s, which was premised primarily on increasing engagement, but less clarity on what changes are needed. The national security case for tariffs on steel and aluminum is even murkier: while there may be a case for ensuring domestic production capacity for these commodities, it isn’t clear tariffs are the best instrument (or that they even achieve this goal). These tariffs antagonized many of America’s closest security partners, particularly Canada, which undermined efforts to cultivate a broader multilateral alliance to challenge China. Moreover, the Trump administration’s frequent recourses to national security on flimsy grounds will make it more difficult for the U.S. to push back when other countries cloak protectionism in tenuous appeals to national security.

What’s at stake in the upcoming election?

If Joe Biden wins, he will likely seek to reverse some of Trump’s more protectionist pushes. In particular, Biden will seek to repair trade relations with allies in North America and Europe, and to work through established channels such as the World Trade Organization (WTO). Yet he appears unlikely to simply return to the trade paradigm of the Clinton, George W. Bush, and Obama administrations. Several Democratic trade policy advisors have argued that Biden should break with earlier, more pro-corporate approaches to trade. For example, Biden’s trade policy would likely have greater emphasis on labor and environmental concerns than in previous administrations. Biden has promised his administration “won’t enter into any new trade agreements until we’ve made major investments here at home, in our workers and our communities” and advocated for a strong Buy American procurement policy. He has sharply criticized Trump’s tariffs on China, but it’s not clear if his administration would maintain them or not. Either way, a Biden administration would almost certainly adopt a more confrontational trade policy with China than Clinton, Bush, and Obama did.

For his part, if Trump wins a second term, we should not necessarily expect just a continuation of his first-term trade policies. While Trump himself has long had protectionist impulses, during his first term his team of advisors was divided between a more establishment, pro-trade group and a more protectionist faction. One result was that, particularly through the early years of his presidency, Trump’s trade rhetoric far outpaced actual changes to policy—Trump’s most aggressive proclamations never came to pass, and when the administration did renegotiate trade deals (such as NAFTA), the changes were quite modest. Over the course of the last three and a half years, however, many of the advisors and officials who restrained Trump’s protectionism have left office, tilting the balance in favor of bolder, more radical policy options. This dynamic would likely extend during a second term, which suggests the Trump administration might be more likely to follow through on some of his more extreme ideas. These include withdrawing from the WTO (though to be sure, this idea would still face strong resistance) and provoking further trade fights with allies such as Europe, Canada, Mexico, and Japan. In a second term, the guardrails that kept Trump’s trade policies from deviating too far from established approaches would further erode, opening the door to more radical changes.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Did Trump’s tariffs benefit American workers and national security?

September 10, 2020