Housing affordability is a financial stress on American families

Housing costs are rising faster than incomes, putting greater financial stress on U.S. families. In 2017, nearly half of renter households spent more than 30 percent of their income on rent, meeting the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s (HUD) definition of being “cost-burdened.” While affordability has long been a problem for poor renters, even middle-income households are facing greater challenges, particularly in urban areas with strong job markets. And where people can afford to live has important implications. Research shows that children who grow up in high-opportunity communities have better economic outcomes as adults. Cities and neighborhoods with strong labor markets and good schools——exactly the places in highest demand——are not building enough new housing, contributing to worsening affordability. Because housing near jobs and transit centers is so expensive, low- and moderate-income people are pushed to cheaper housing on the outskirts of metropolitan areas, requiring them to spend more time and money commuting.

Why better alignment of three housing policies would help

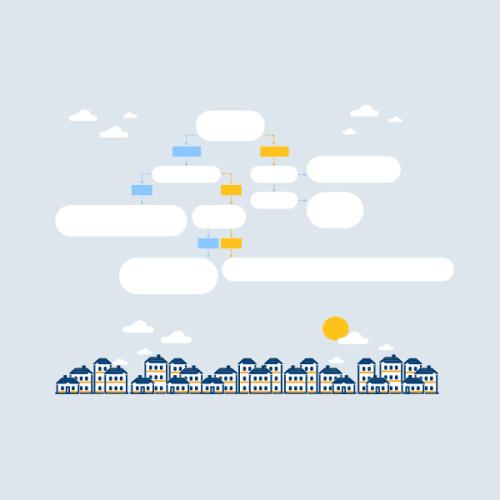

Just as health care reform under the Affordable Care Act was designed as a “three-legged stool,” improving housing affordability will require better alignment of three policy tools: reforming land use regulation to allow smaller, more compact housing; increasing taxes on expensive, underused land; and expanding housing subsidies to low-income households. Each of these changes are described in more detail below.

First leg: zoning reform

The U.S. needs to build more housing, and less expensive housing, especially in high-opportunity communities. To accomplish that, local governments must reduce regulatory barriers that limit the market’s ability to build small, lower-cost homes on expensive land. For example, local zoning regulations prohibit building anything other than single-family detached houses on three-quarters of land in most U.S. cities. Townhouses, duplexes, and apartment buildings are simply illegal. Even where multifamily buildings are allowed, zoning rules like building height caps and minimum lot sizes often limit the financial feasibility of developing new housing. Single-family houses use more land per home than other housing types. Therefore, in places where land is expensive, building multiple homes on a given lot is the most direct way to reduce housing costs, because it spreads the cost of land across multiple homes.

A simple numerical example illustrates how redeveloping existing single-family lots with more compact housing types can improve affordability (Table 1). A typical single-family lot in Washington, D.C., is large enough to accommodate three side-by-side townhomes or a three-story, six-unit condominium building. Based on prevailing construction costs and financing terms, a developer could profitably build three new townhomes that would sell for just under $1 million each—about the same price as an older, poor condition single-family home on the same lot. Or the developer could build six two-bedroom condos, each priced around $580,000—roughly 40% cheaper. While the numbers used for this analysis are for Washington, D.C., the financial implications—adding more homes to a single lot reduces per-unit costs—are similar in other high-priced markets across the U.S.

Redeveloping older, low-density buildings with new, high-density buildings is quite common in expensive cities—except in the wealthiest neighborhoods where affluent homeowners use their financial and political resources to block most new housing. City-wide zoning reforms that open up those neighborhoods to townhomes, duplexes, and small apartment buildings would substantially increase the supply of housing, while also making those communities financially accessible to many more families.

Several of the 2020 Democratic presidential candidates have proposed plans to address housing affordability through relaxing exclusionary zoning. The issue has bipartisan appeal: the White House has issued an Executive Order to reduce regulatory barriers to affordable housing. Making progress on this issue will require cooperation across federal, state, and local governments.

Second leg: land value tax

Removing barriers to developing apartments would eventually lead to more housing in expensive neighborhoods over time. However, the transition would happen faster—and more equitably—if that effort were paired with higher taxes on land. The concept of taxing land dates back to the 19th century, when Henry George proposed it to prevent wealthy landowners from artificially limiting the supply of homes. Unlike typical property taxes, which charge the same rate on both land and structures, taxes that charge a higher tax rate on land and a lower rate on structures encourage owners of expensive land to build more intensively. Pure land value taxes that exempt structures altogether are quite rare in practice, compared to “split rate” taxes.

For example, consider the development incentives for the owner of a downtown parking lot in expensive cities like Boston or Los Angeles. Under a typical property tax regime, the owner would owe more taxes if she built an apartment building on the lot. But under a land value tax, the owner would face the same tax bill whether the land was developed for parking, apartments, office space, or any other use.

One concern about zoning reforms that allow higher density development is that such upzoning increases property values, creating windfall gains for existing property owners. Upzoning could also encourage landowners to delay development as they await the opportunity to build larger, denser buildings. Assessing taxes on the increased land value not only incentivizes more development more quickly on expensive land, but also allows local communities to capture some of the returns on additional land value. This feature of land value taxes is especially attractive in locations where the local government has made investments that increase land values, for instance by building public transit. Imposing a land value tax in locations already developed to maximum capacity without relaxing zoning would hand landowners a larger tax bill, but not enable more housing supply.

Land value taxes paired with upzoning would similarly change incentives for owner-occupants of large single-family homes in expensive locations. Zoning reforms that allow higher density housing would increase land values and, under land value taxes, yield higher tax bills. Current owners who treasure their yard space could keep their single-family homes as-is and pay the taxes. But some homeowners might decide to subdivide their homes (for instance, turning garages into accessory dwelling units) or sell their properties to developers. From the upzoning example, a land value tax bill would be the same if the lot remained a single-family home or was redeveloped as townhouses or condos. But the tax bill would be split across three households under the townhouse scenario, or six households under the condo scenario, just as the land costs would be shared.

Land is most expensive in city centers, near job clusters and transportation nodes. Land value taxes primarily change financial incentives for owners of expensive land with low density structures. The increased density encouraged by shifting to a land value tax would enable more people to live near work, reducing commuting distances. If all communities within a state adopted land value taxes, single-family homes on inexpensive land far from city centers or in low-cost metros would be less affected.

Third leg: More housing subsidies

Building more housing, especially smaller housing, will over time bring down housing costs (or at least keep them from rising as quickly). But expanding the supply of market-rate housing is not enough to help the poorest families. For the 14 million low-wage workers with median income around $20,000, HUD guidelines suggest they should spend no more than $500 per month on housing costs. That’s less than the operating expenses for minimum quality apartments in most of the U.S. For low-income families, the only way to bridge the gap between incomes and housing costs is through public subsidies.

The federal government could reduce financial stress for low-income families by expanding housing subsidies, like vouchers or the National Housing Trust Fund. Unlike food stamps or Medicaid, federal housing subsidies are not an entitlement: currently around one in five eligible renter households receives federal assistance. Alternatively, supplementing incomes through the Earned Income Tax Credit or higher minimum wages would help poor families pay the rent.

In one sense, more subsidies for poor families is independent of zoning and tax reforms—housing affordability has been an urgent concern for many years. But upzoning and moving to land value taxes could worsen affordability pressures. In hot real estate markets, these two policies would likely prompt redevelopment of older, low-density, low-rent apartments into new, larger buildings that are out of reach for existing renters. Expanding housing vouchers to cover more families would therefore help protect low-income renters from displacement. It is also possible that expanding housing subsidies without enabling more supply through zoning reform would push up rents in some markets.

Implementation questions and challenges

The economic intuition behind zoning reform, land value taxes, and increased housing subsidies is straightforward, but implementing these policies poses some challenges. Single-family-exclusive zoning benefits long-term homeowners, also known as highly engaged voters. Mayors and city councils face stiff opposition from their constituents from proposing zoning reform. State and federal policymakers are increasingly interested in how to encourage zoning reform, but have limited direct control. This raises the question: are there financial or legal levers that could effectively encourage local governments to reform their zoning—especially when the most exclusionary localities are wealthy?

Like zoning, property taxes are largely the domain of local governments, although states create the legal framework under which localities operate. Some states might have to amend their constitutions to permit a “split” property tax, with different tax rates applied to land and structures. One technical challenge is that accurately assessing market values for land, separate from structures, is not easy. But a new dataset created using appraisal data from the Federal Housing Finance Administration is highly promising.

Expanding vouchers is legally and procedurally simple. It just requires Congress to demonstrate the political will to spend more money on poor people. Low-income families who receive federal housing vouchers rent apartments from private landlords. Families pay thirty percent of their income toward rent, with the remainder picked up by HUD. Vouchers reduce financial stress, crowding, and the risk of homelessness among low-income families. Recent research shows that with relatively inexpensive program changes, vouchers can also help poor families move to neighborhoods that offer better economic opportunity.

In conclusion, better housing policy has the potential to improve the efficiency of local housing markets, create more homes in high opportunity locations, and provide financial relief to low-income families. It represents a way to gain substantial payoffs for people and a way to tackle big challenges in America.

Thanks to Sarah Crump for outstanding research assistance.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).