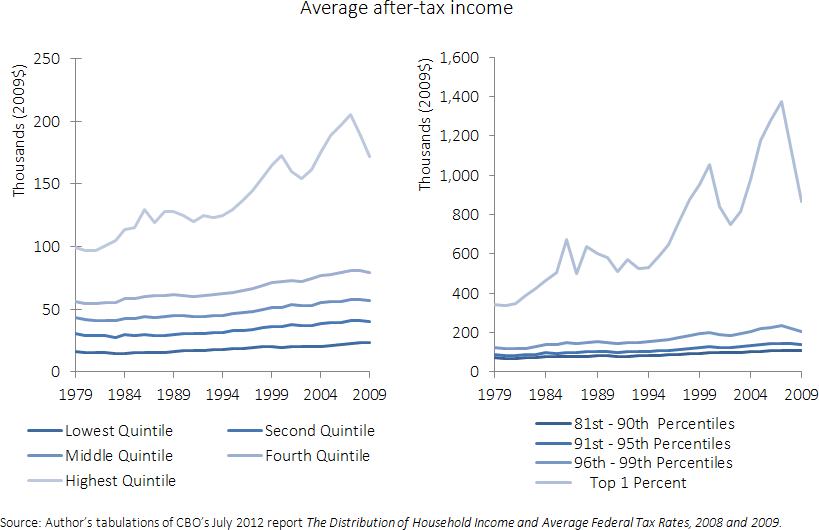

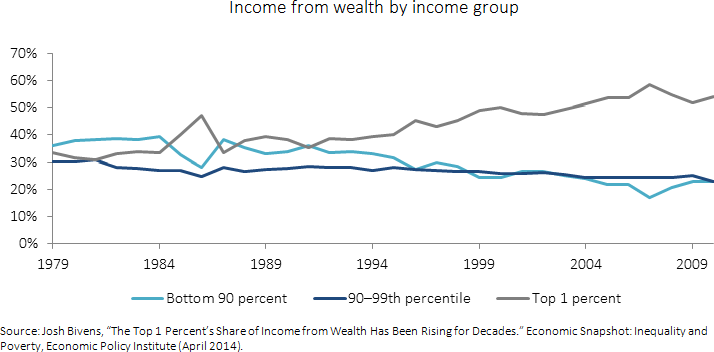

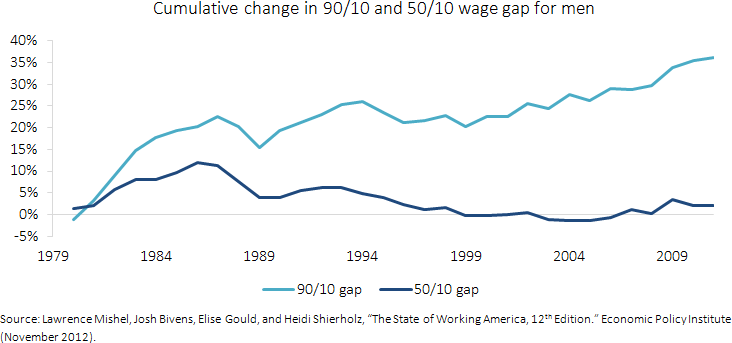

Everyone knows that inequality in the United States has risen in recent decades. And anyone who has looked at any data – or an earlier post from my Brookings colleague Gary Burtless – also knows that most of this rise is explained by the pulling away of the rich from everyone else. Whether you look at income:

Or wealth:

Or wages:

The implications of this particular kind of inequality are quite profound. Not only for politics, policy, and political economy, but even for political philosophy. In recent history, concerns about equality have been, at heart, concerns about the poor. Even now the popular framing of inequality is very often along the lines of “the gap between rich and poor.” Egalitarian political philosophers have tended to adopt a version of John Rawls’ “difference principle” – that inequalities are only acceptable to the extent that they help the worst-off in society, for example by incentivizing overall economic growth. The overarching goal has been to ensure that the poor do not fall behind the majority.

Many social policies are anti-poverty policies of one form or another, whether or not they are described as such: targeted income transfers, additional services for poor families, or subsidized savings or health care. This anti-poverty impulse lay behind many of the social programs of the Great Society. The evidence is that the “war on poverty” was successful, in the sense that poverty has been prevented from rising.

So what happens when the poor are keeping up with the majority, but the majority are falling behind the elite? You might say that keeping up is not good enough, and that we should still be trying hard to close the poor-middle gap. That would be a fair point. You might also say that one reason the poor are keeping up with the middle is that the middle aren’t doing very well. Also a fair point: though a rather different one.

The Rich: Always With Us?

The forces driving the gap between the top and the majority are not likely to pass. Higher returns to education, “assortative mating” (like marrying like), gaps in family structure and parenting, and geographical segregation are deep-seated economic and social trends. They would not be easy to curb, even with quite aggressive policy interventions. Scholars like Sean Reardon suggest that gaps in educational attainment are growing in the top half of the distribution, not the bottom. Work by family researchers, including Isabel Sawhill in her new book Generation Unbound, points to a growing divide between college-educated Americans and the rest in terms of marriage, intentionality of childbearing and family stability. (I summarized some of these trends in a recent talk to the Queen’s Institute of International Social Policy, my slides are here.) Top-majority inequality, then, is likely to be an important pattern in coming years.

The question is, how do we react? Probably in one of three ways:

Reaction 1 to Top-Majority Inequality: Don’t care.

The first reaction is indifference. If inequality in the majority of the population is unchanged, perhaps it really doesn’t matter if the top decile is doing a bit better, and the top percentile doing a whole lot better. It might make some people angry. But it might make others inspired to try and reach the top. So long as the elite are paying their taxes, and not buying the political system, perhaps we all just need to relax. Of course, sometimes they are not paying their taxes, and the structure of political funding means they may well have disproportionate influence: but in theory at least, these problems could be addressed independently.

Others may argue in return that redistribution from those at the top would ease the plight of those lower down. True – but only up to a point. Redistribution from a small group at the top to the whole of society has limited impact, for the simple reason that the money is being spread around so thinly. You only need to take a bit of money from the top 90% to help the bottom 10%; you need to take a lot from the top 10% to help the bottom 90%.

Reaction 2 to Top-Majority Inequality: Do care.

If the big problem is the pulling away of the top from the middle, perhaps policy should be focused on helping the middle. The “new poor” are now arguably the majority, at least compared to the lucky few at the top. So policies could be explicitly aimed at helping the middle. This could mean more tax breaks or tax credits for those on average incomes. Rather than using income tests to focus benefits on the poor, perhaps they could be used to screen out the affluent. The UK government, for example, now gives child benefit to all parents except those making over 50,000 pounds a year. Rather than being universal, or being targeted on the poor, transfer payments and/or services could be for the “ordinary majority” – in other words, for everyone except the rich.

A more radical approach would be the creation of new social insurance schemes designed to top up in incomes or wages for ordinary workers. Economist Lane Kenworthy has suggested a scheme that pays out to employees whose wages fall behind the average growth of the economy. Perhaps this could be funded by much higher taxes on capital gains and inheritance – which only seriously impact on those at the top. Alternatively, we might consider a version of an unconditional basic income (UBI), currently attracting some interest on both the left and right. In light of current inequality trends, perhaps a basic income could be “conditional” in the sense of not going to the affluent. We might withdraw the benefit once somebody’s earnings hit $100,000 a year, for instance.

Reaction 3 to Top-Majority Inequality: Don’t care, unless…

The third reaction to the top-majority gap is to worry about opportunity rather than money: or rather, only money in the sense that it influences opportunity. You might be reasonably relaxed about the affluent doing so well, so long as poverty is not rising – and so long as the children of today’s rich are not automatically going to be tomorrow’s rich. Clearly, wealth and capital taxes will be important here. But there are more important factors that could help those at the top to pull away not only in terms of today’s resources, but in terms of opportunity too. By investing heavily in education, leveraging social capital and networks, and providing buffers against downward shocks, the elite may be able to hoard opportunities for their own children, creating a “glass floor” so that they cannot fall too far.

Opportunity hoarding is otherwise known as committed parenting. All of us want our own kids to do as well as possible. But when this natural instinct interacts with social and economic institutions, we must pay attention. Snagging internships at the law firm of your father’s golf partner, or gaining an alumni place at top university (when, not coincidentally, parental gifts to their alma mater peak) are the kinds of practices that we might come to question more closely if the top-majority inequality pattern remains.

There is already some evidence that the sons of the top 1% of earners are more likely to stay near the top of the earnings ladder in the US than in Canada. This could be a red flag for the future. It is one thing for the top 1% to do well; quite another for them to reserve a place for their children at the top of the ladder.

Conclusion: The New Egalitarianism

It is easy to wonder if politicians proclaiming their support for the “middle class” rather than the “poor” are simply disguising their progressive, redistributive instincts in more voter-friendly language. But maybe there is something deeper going on now. Perhaps politicians are sensing that equality is no longer principally about poverty, but about wealth. A refashioning of political egalitarianism could be the result.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Op-edInequality at the Top: Why Should we Care?

September 16, 2014