Last year, for the first time in more than nine decades the major cities of the nation’s largest metropolitan areas grew faster than their combined suburbs. At least temporarily, this puts the brakes on a longstanding staple of American life—the pervasive suburbanization of its population—which began with widespread automobile use in the 1920s to the present day when more than half the U.S. population lives in the suburbs.

This reversal is identified in an analysis of newly released Census Bureau data for 2010-2011 and can be attributed to a number of forces. Some are short- term and related to the post 2007 slowdown of the suburban housing market, coupled with continued high unemployment which has curtailed population mobility, now at a historic low.

However, at least some cities may be seeing a population renaissance based on efforts to attract and retain young people, families and professionals.

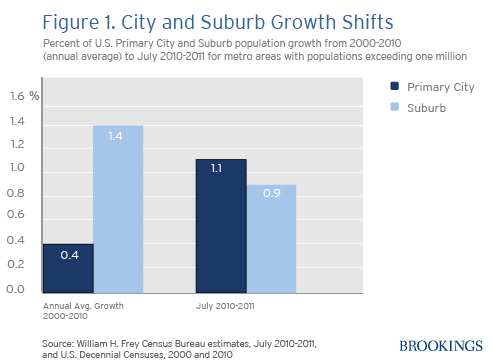

While these forces have led to lower suburban growth and increased city retention toward the end of the 2000s, the new data show a notable tipping point. Using the Brookings definition, core “primary cities” of the nation’s 51 metropolitan areas with populations exceeding one million, grew faster than the suburbs of those areas between July 2010-2011. Cities grew at 1.1 percent while suburbs grew at 0.9 percent. This contrasts with suburban dominated growth in the 2000s, extending the pattern previous decades.

Among the 51 largest metro areas, primary city growth exceeded suburban growth in 27 over the last year, compared with just five in the 2000s decade (see table). Moreover, compared with annual average rates in the 2000-2010, 43 metropolitan areas showed faster primary city growth in 2010-11 while 43 registered slower growth in their suburbs.

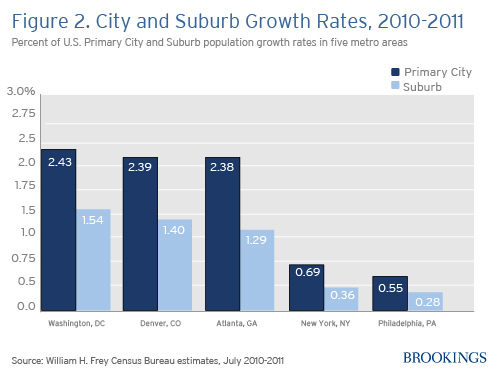

Among the metropolitan areas with sharp sharpest city growth advantages are Washington D.C., Denver and Atlanta, where annual city growth ramped up for 2010-2011 and exceeded suburb growth by about 1 percent. This contrasts with the 2000s decade when suburbs grew substantially faster than the suburbs in all three. As in most of the country, their suburbs disproportionately bore the brunt of the late 2000s housing collapse. However, all three have important urban amenities and economic bases that are attractive to young people and other households now clustering in their cities.

While these are extreme examples of the recent reversal, city gains and suburban downturns are evident in all parts of the country, including the Northeast and Midwest

This is the case for New York, Philadelphia, Kansas City, and Columbus. In Chicago, Pittsburgh, Milwaukee, Rochester, and Minneapolis-St Paul, city declines in the 2000s turned to gains in 2010-2011. At the same time, the city declines of the 2000s lost momentum in 2010-2011 in Detroit, Cleveland, Buffalo, St Louis, and Cincinnati.

Beyond the aforementioned city gainers over the last decade, other Sun Belt and Western examples are Austin, Seattle, Salt Lake City, Houston, Tampa-St Petersburg, Dallas, Memphis, and Birmingham. In New Orleans, Miami, San Francisco, and San Jose both city and suburbs showed higher growth in 2010-2011 compared to their annual average in 2000-2010.

In fact, the only Sun Belt city growth slowdowns occurred where entire metropolitan areas were hard hit by last decade’s housing slowdown. Among these are Las Vegas, Sacramento, Orlando, Jacksonville, Raleigh, and Charlotte. In each case, both cities and suburbs registered lower growth in 2010-2011 than their annual average of the 2000s, with suburbs taking the greatest hit.

This new ‘tipping point” clearly has its origins in the downturns in the national housing and labor markets of the past five years. Young people, retirees, and other householders who might have moved to the suburbs in better times are unable to obtain mortgages or employment. Many remain stuck in rented or shared homes that are more often located in cities. Yet what may look like a temporary lull in the broad sweep of suburban development may turn out to be an opportunity for some cities to showcase their oft cited lifestyle and cultural amenities to a new generation of residents and developers, so that in some regions a new version of the American Dream could take root.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Op-edDemographic Reversal: Cities Thrive, Suburbs Sputter

June 29, 2012