More On

China’s state leaders were revealed on March 18, 2018 at the conclusion of the 13th National People’s Congress (NPC). Most notably, the NPC approved a constitutional change abolishing term limits for China’s president Xi Jinping. Below are background profiles for the seven top government leaders. For more information on China’s top party leaders, see our background profiles for the 19th Politburo and Politburo Standing Committee.

Top Government Leaders

Profiles of the Top Government Leaders

Download Profile as PDF

Download Profile as PDF

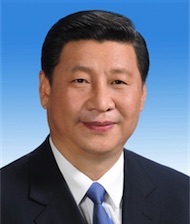

Xi Jinping 习近平

- Born 1953

- President of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) (2013–present)

- General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) (2012–present)

- Chairman of the Central Military Commission (CMC) (2012–present)

- Member of the Politburo Standing Committee (PSC) (2007–present)

- Chairman of the National Security Committee (2013–present)

- Head of the Central Leading Group for Comprehensively Deepening Reforms (2013–present)

- Head of the Central Leading Group for Foreign Affairs and National Security (2013–present)

- Head of the Central Leading Group for Taiwan Affairs (2012–present)

- Head of the Central Leading Group for Financial and Economic Work (2013–present)

- Head of the Central Leading Group for Network Security and Information Technology (2014–present)

- Head of the CMC Central Leading Group for Deepening Reforms of National Defense and the Military (2014–present)

- Commander in Chief of the Joint Operations Command Center of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) (2016–present)

- Chairman of the Central Military and Civilian Integration Development Committee (2017–present)

- Member of the Politburo (2007–present)

- Full member of the Central Committee of the CCP (2002–present)

Personal and Professional Background

Xi Jinping was born on June 15, 1953, in Beijing. His ancestral home is Fuping County, Shaanxi Province. Xi was a “sent-down youth” at an agricultural commune in Yanchuan County, Shaanxi (1969–75)1. He joined the CCP in 1974. Xi received his undergraduate education in chemical engineering from Tsinghua University in Beijing (1975–79) and later graduated with a doctoral degree in law (Marxism) from the Institute of Humanities and Social Sciences at Tsinghua University (via part-time studies, 1998–2002).

Early in his career (1979–82), Xi served as a personal secretary (mishu) to Geng Biao, then minister of defense. Subsequently, Xi served as deputy secretary and then secretary of Zhengding County, Hebei Province (1982–85), and thereafter in Fujian Province as executive vice-mayor of Xiamen City (1985–88), party secretary of Ningde County (1988–90), party secretary of Fuzhou City (1990–96), deputy party secretary of Fujian Province (1996–99), governor of Fujian Province (1999–2002). After his time in Fujian, Xi served as governor of Zhejiang Province (2002) and party secretary of Zhejiang Province (2002–07). In March 2007, Xi was appointed party secretary of Shanghai. Seven months later, he was transferred to Beijing to serve as a Politburo Standing Committee member (2007–present) and executive secretary of the Secretariat of the CCP Central Committee (2007–12). In March 2008, he was elected PRC vice-president (2008–13). Xi was in charge of preparations for both the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing and the 2009 celebrations commemorating the sixtieth anniversary of the founding of the PRC. He also served as president of the Central Party School (2007–12), the most important venue for training officials and ideological/policy research in the CCP. Xi was reelected as general secretary of the CCP and chairman of the CMC at the 19th Party Congress in October 2017, and then as president of the PRC at the 13th National People’s Congress in March 2018. He was first elected to the Central Committee as an alternate member at the 15th Party Congress in 1997.

Family and Patron-Client Ties

Xi is a princeling; he is the son of Xi Zhongxun, a former Politburo member and vice-premier who was one of the architects of China’s Special Economic Zones in the early 1980s2. Xi Jinping is widely considered to be a protégé of both former PRC president Jiang Zemin and former PRC vice-president Zeng Qinghong. Xi’s first marriage produced no children. His ex-wife, Ke Lingling, is the daughter of Ke Hua, former PRC ambassador to the United Kingdom, where Ke Lingling now lives. Xi’s current wife, Peng Liyuan, is from his second marriage. Peng is a famous Chinese folksinger who, until recently, served in the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) at the rank of major general. She served as president of the PLA General Political Department Song and Dance Troupe and president of the PLA Art Institute. Their only daughter, Xi Mingze, received her undergraduate degree in psychology from Harvard University (2010–14) and later pursued a graduate program in the same field at a university in Beijing.

Political Prospects and Policy Preferences

Over the course of his first term, Xi has proven himself to be China’s strongest leader since Deng Xiaoping. Of the many noteworthy developments from this period, the following three efforts stand out:

Anti-Graft Campaign – With the support of his principal political ally in the PSC, “anticorruption czar” Wang Qishan, Xi launched a remarkably bold national anti-graft campaign. The campaign has resulted in the purges of not only retired heavyweight leaders such as former PSC member Zhou Yongkang, but also about 11 percent of the members of the 18th Central Committee, including Politburo member Sun Zhengcai. To some extent, the overriding objective of his anti-corruption campaign has been to restore the Chinese public’s faith in its ruling party, which lost public trust in the wake of the Bo Xilai scandal and the Ling Jihua incident.3

Military Reform – Xi achieved a milestone victory in restructuring the PLA, through efforts which have been officially referred to as “military reform” (军队改革). Reform efforts have centered on marginalizing the four PLA general departments that had undermined the authority of the civilian-led CMC; transforming China’s military operations from a Russian-style, army-centric system toward what analysts call a “Western-style joint command” system; and swiftly promoting “young guards” to top positions in the officer corps. Of the 66 military members of the 19th Central Committee, 60 (91 percent) were newcomers.4

Proactive Foreign Policy – Xi’s “proactive” (奋发有为) approach to foreign policy marks a significant departure from Deng Xiaoping’s strategy of “keeping a low profile” (韬光养晦). Xi’s efforts have sought to showcase China’s rapid rise on the world stage under his leadership, including through the launch of the “Belt and Road Initiative” and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), and China’s deepening engagement in international institutions and forums, most notably his speech at the Davos World Economic Forum in 2017. His efforts have also included concerted attempts to seek a “new model of great power relations” with the United States.

On other policy issues, however, Xi has exhibited paradoxical preferences and tendencies. For example, the objective of his economic policy, as articulated at the third plenum of the 18th Central Committee in 2013, has been to make the private sector the decisive driver of the Chinese economy. Yet, Xi continues to favor China’s industrial policy and has called for making flagship state-owned enterprises “bigger and stronger.”

His attitude toward public intellectuals has proven similarly ambivalent. On the one hand, Xi has promoted Chinese think tanks, which are mostly staffed with academics. On the other, his politically conservative approach to governance—in particular, his reliance on ideological oversight and media censorship—has left him at loggerheads with many of the country’s intellectuals. A similar tension exists in Xi’s approach to legal reforms. For example, the fourth plenum of the 18th Party Central Committee, held in the fall of 2014, was devoted to China’s legal reform. This marked the first time in CCP history that a plenum concentrated on law. Further, Xi’s work report at the 19th Party Congress established the Central Leading Group of Rule of Law in the party and a constitutional review system in the state. It seems that Xi, more than any previous top leader, is interested in having his legacy centered on the development of rule of law and the judiciary in China. Yet, critics often point to the arrests and harassment of human rights lawyers in China as examples that the rule of law in China has actually regressed under Xi’s leadership.

Some of this cognitive dissonance may be temporary compromises as Xi positions himself to gain broad support from various forces in the country. If Xi aspires to be a truly great and transformative Chinese leader, he must eventually present a clear and coherent vision for the country while also respecting the political rules and norms that have laid the groundwork for China’s economic and political rise.

The recent NPC meeting has proposed removing a clause from the country’s constitution—added during the Deng Xiaoping era—which limits both the presidency and vice presidency to two five-year terms. Undoing this restriction essentially lines Xi up to be “President for Life.” It appears that Xi has seized upon his moment at the pinnacle of accrued political capital to avoid becoming a lame duck and to cement his hold over the country for as long as he desires.

This latest action by Xi alienates two critical constituencies, whose power Xi may be underestimating. Intellectuals will be among the first to push back and shape the public discourse. They have been disillusioned by Xi’s leadership since 2013, when authorities began cracking down on open discussion of “seven subversive currents,” including universal values, constitutional democracy, human rights, civil society, and media freedom. Their perceptions of Xi as a Mao-like figure may now be crystallized.

The political establishment, while certainly composed of some “yes-men” willing to do the president’s bidding, is by no means monolithic. Some political elites may stand up for their belief in the institutionalized norms of the Deng era. Others may see Xi’s reversal of constitutional constraints on term limits as heralding a return to an era of vicious power struggles—a zero-sum game in which they will also ruthlessly engage in the years to come.

Compiled by Cheng Li and the staff of the John L. Thornton China Center at BrookingsNotes

- “Sent-down youth” (插队知青) refers to young, educated urbanites who left their home cities to serve as manual laborers in the countryside during the Cultural Revolution.

- For more information on Xi’s family background and his early life experiences, see Liang Jian 梁剑, New Biography of Xi Jinping [习近平新传] (New York: Mirror Books, 2012), and Wu Ming 吴鸣, Biography of Xi Jinping [习近平传] (Hong Kong: 文化艺术出版社, 2008).

- For a detailed discussion of these cases, see Cheng Li, Chinese Politics in the Xi Jinping Era: Reassessing Collective Leadership (Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution Press, 2016), pp. 1–5, 23–24.

- This includes four military alternate members of the 18th Central Committee who were promoted to be full members of the 19th Central Committee. If these four leaders are excluded, 85 percent would be newcomers.

Download Profile as PDF

Download Profile as PDF

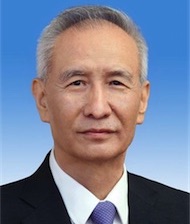

Wang Qishan 王岐山

- Born 1948

- Vice president of the People’s Republic of China (2018–present)

Personal and Professional Background

Wang Qishan was born in 1948 in Tianzhen County, Shanxi Province1. Wang was a “sent-down youth” at an agricultural commune in Yan’an County, Shaanxi (1969-1971)2. Wang was a staff member at the Shaanxi Museum (1971–73 and 1973–79) before he joined the CCP in 1983. He received his undergraduate education from the history department at the Northwestern University in Xi’an City, Shaanxi Province (1976). Early in his career, Wang worked as a researcher and director at the Institute of Contemporary History of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (1979–82) and then moved to the Rural Policy Research Office of the CCP Central Committee (1982–88).

Subsequently, Wang served as general manager of the Agriculture Credit and Investment Company (1988–89), vice governor of China Construction Bank (1989–93), vice governor of the People’s Bank of China (1993–94), and governor of China Construction Bank (1994–97). Wang was transferred to Guangdong Province in 1997 to serve as vice governor. Three years later, in 2000, he was appointed director of the State Council General Office of Economic Reform. Wang then worked as party secretary of Hainan Province (2002–03). At the peak of the SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome) crisis, Wang was appointed mayor of Beijing (2004–07). He then became vice premier of the State Council (2008–13), a Politburo member (2007–17), and a Politburo Standing Committee Member (2012–17). Wang most recently served as secretary of the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (2012–17). He was first elected to the Central Committee as an alternate member at the 15th Party Congress (1997).

Family and Patron-Client Ties

Wang’s father was a professor at Tsinghua University who also worked as an engineer at the Design Institute in the Ministry of Construction. As the son-in-law of Yao Yilin, a former Politburo Standing Committee member and vice premier, Wang is considered a princeling. Wang is married to Yao Mingshan. The two met in 1969 in Yan’an, where both were sent-down youths. Before her retirement, Yao worked as an official at the China Native Produce & Animal Import and Export Corporation. The couple does not have any children.

Wang is widely considered to be a protégé of both Zhu Rongji and Jiang Zemin. During his work in the financial sector in the 1990s, Wang established his patron/mentor relationship with Zhu, who was in charge of China’s financial affairs at the time. Wang’s patron/mentor ties with Jiang Zemin stem in part from Wang’s father-in-law, Yao Yilin, who was a major supporter of Jiang in the Politburo Standing Committee, and in part from Wang’s close friendship with Jiang’s son, Jiang Mianheng.

Xi Jinping’s close relationship with Wang Qishan has arguably been the most important factor facilitating the consolidation of Xi’s power and the implementation of his new policy initiatives since Xi took the top leadership post in 2012. It is not clear when Xi and Wang first met. However, several Chinese sources reveal that Wang and Xi became close friends over forty years ago, when both were “sent-down youths” in two neighboring counties in Yan’an.3

Political Prospects and Policy Preferences

Wang Qishan is viewed by the Chinese public as capable in crisis situations. In particular, his management of the SARS epidemic in the spring of 2003 has been taken as evidence of his efficacy in crisis.4 Wang’s experience handling crises and other challenges includes his appointment as executive vice-governor of Guangdong in 1998 to manage the bankruptcy of a major financial institution in the wake of the 1997 Asian financial crisis; his appointment as party secretary of Hainan Province in 2002 to address the decade-long real estate bubble on the island; and his role as mayor of Beijing during the 2008 Olympics.5

Wang is widely recognized in China by the nickname “chief of the fire brigade” (救火队长). Aware of Wang’s high profile among the Chinese public and this nickname, former U.S. Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner presented Wang with an authentic New York City Fire Department hat during Wang’s visit to the United States in 2011.6

During Xi’s first term, Wang Qishan was Xi’s strongest political ally and acted as the party’s “anticorruption czar.” Wang launched the largest anti-graft campaign in the PRC history, purging approximately 440 leaders at the vice-ministerial and vice-provincial levels (副省部级) on corruption charges, including 79 PLA officers holding the rank of major general or higher and 45 members of the CCP’s 18th Central Committee.7

Wang Qishan’s toughness, popularity among the Chinese public, expertise in finance, and international reputation have made him indispensable to Xi. However, Wang has ostensibly also made many political enemies. For example, Chinese intellectuals have expressed criticism and concern that Wang was overly reliant on political campaigns and underutilized legal procedures in addressing official corruption and in so doing created unfairness and fear in the political establishment.

Wang will likely assist Xi in two important fields: China-U.S. relations and the “Belt and Road Initiative.” Both tasks will be very challenging due to the rapidly changing international environment. How the relationship between these two strongmen in China, Xi and Wang, will unfold in the years to come remains to be seen.

Compiled by Cheng Li and the staff of the John L. Thornton China Center at BrookingsNotes

- Some unofficial biographers say he was born in Qingdao City, Shandong Province, and that Tianzhen was his ancestral home.

- “Sent-down youth” (插队知青) refers to young, educated urbanites who left their home cities to serve as manual laborers in the countryside during the Cultural Revolution.

- Zhang Lei, “Nongchaoer” [The man who paddles against the incoming tide], Nanfang Renwu Zhoukan [Southern People Weekly], August 26, 2013; and Wu Rujia and Lin Zijing, “Wang Qishan lianpu” [Changing roles of Wang Qishan], Fenghuang Zhoukan [Phoenix Weekly], December 5, 2013.

- Cheng Li, Chinese Politics in the Xi Jinping Era: Reassessing Collective Leadership (Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution Press, 2016), p. 268.

- Ibid., pp. 313-314.

- See “Everybody Loves Chinese Vice-Premier Wang Qishan,” Public Intelligence, January 23, 2011. (https://publicintelligence.net/everybody-loves-chinese-vice-premier-wang-qishan/).

- See“Xi Jinping’s Personal Secretary Suddenly Speaks Prior to China’s Two Conferences: Some People Are Attempting An Internal Coup In the Party.” [习近平大秘两会前突发声:有人想篡党夺权] Boxun, February 25, 2018. (https://boxun.com/news/gb/china/2018/02/201802251958.shtml), and also Cheng Li’s research.

Download Profile as PDF

Download Profile as PDF

Li Keqiang 李克强

- Born 1955

- Premier of the State Council (2013–present)

- Member of the Politburo Standing Committee (2007–present)

- Vice-Chairman of the National Security Committee (2013–present)

- Deputy Head of the Central Leading Group for Comprehensively Deepening Reforms (2013–present)

- Deputy Head of the Central Leading Group for Financial and Economic Work (2013–present)

- Vice-Chairman of the Central Military and Civilian Integration Development Committee (2017–present)

- Chairman of the Committee on Organizational Structure of the Central Committee of the CCP (2012–present)

- Chairman of the National Defense Mobilization Committee (2013–present)

- Director of the State Energy Commission (2013–present)

- Head of the National Leading Group for Climate Change and for Energy Conservation and Reduction of Pollution Discharge (2013–present)

- Head of the State Council Leading Group for Rejuvenating the Northeast Region and Other Old Industrial Bases (2013–present)

- Head of the State Council Leading Group for Western Regional Development (2013–present)

- Head of the State Council Three Gorges Project Construction Committee (2008–present)

- Head of the State Council South-to-North Water Diversion Project Construction Committee (2008–present)

- Head of the State Council Leading Group for Deepening Medical and Health System Reform (2008–present)

- Member of the Politburo (2007–present)

- Full member of the Central Committee of the CCP (1997–present)

Personal and Professional Background

Li Keqiang was born on July 1, 1955, in Dingyuan County, Anhui Province. Li joined the CCP in 1976. He was a “sent-down youth” at an agricultural commune in Fengyang County, Anhui (1974–76)1. He served as party secretary of a production brigade in the county (1976–78). Li received both a bachelor’s degree in law (1982) and a doctoral degree in economics (via part-time studies, 1994) from Peking University. As an undergraduate majoring in law, Li studied under Professor Gong Xiangrui, a well-known, British-educated expert on Western political and administrative systems. Li and his classmates translated important legal works from English into Chinese, including Lord Denning’s The Due Process of Law and A History of the British Constitution2. As a Ph.D. student in economics, Li studied under Li Yining, a well-known economist whose theories have been instrumental in guiding China’s state-owned enterprise reform.

Li advanced his early career primarily through the Chinese Communist Youth League (CCYL), serving as secretary of the CCYL Committee at Peking University (1982–83). Within the Secretariat of the CCYL Central Committee, Li served as alternate member (1983–85), secretary (1985–93), and first secretary (1993–98). In 1998, Li was transferred to Henan Province, where he served as governor (1998–2003) and, concurrently, deputy party secretary (1998–2002) and then party secretary (2002–04). Li then served as party secretary of Liaoning Province (2004–07). In October 2007, he was promoted to Politburo Standing Committee member (2007–present) and, shortly thereafter, served as executive vice premier of the State Council (2008–13). He was first elected to the Central Committee as a full member at the 15th Party Congress in 1997. Li remained on the Politburo Standing Committee after the 19th Party Congress and retained his premiership for a second term at the 13th National People’s Congress in March 2018.

Family and Patron-Client Ties

Li comes from a mid-level official family. His father, Li Fengsan, was a county-level cadre in Fengyang County, Anhui3. Li’s wife, Cheng Hong, is currently a professor of English language and literature at Capital University of Economics and Business in Beijing. She received her undergraduate degree in English at the PLA Foreign Language Institute in Luoyang and her doctoral degree in literature at the Chinese Academy of Social Science. She was a visiting scholar at Brown University in the mid-1990s. Li’s father-in-law, Cheng Jinrui, served as deputy secretary of the Henan Provincial CCYL Committee. Li’s mother-in-law, Liu Yiqing, was a journalist at the Xinhua News Agency. Li Keqiang and Cheng Hong have one daughter, who received her undergraduate degree from Peking University and later studied in the United States, according to some unverified sources.

Li is widely considered to be a protégé of Hu Jintao. Li began working in the CCYL Central Committee at the end of 1982, precisely when Hu Jintao became secretary of the CCYL. Li Keqiang worked closely with Hu, assisting him in convening the Sixth National Conference of the All-China Youth Federation in August 1983. Having been nominated by Hu, Li was promoted to alternate member of the CCYL Secretariat three months later. When Hu was made first secretary of the CCYL in 1985, Li became a full member of the Secretariat. For most of the Hu era, Li was seen as a possible successor to his mentor.

Political Prospects and Policy Preferences

In comparison to his two predecessors, Premier Zhu Rongji and Premier Wen Jiabao, Li Keqiang’s power and authority are noticeably limited—even on economic policy, which has traditionally fallen under the purview of the premier. Observers argue that Premier Li has been marginalized, as Xi has taken over all of the top posts in economic affairs4. Nevertheless, in his first term as premier, Li promoted a number of policy priorities. These include township-centered urbanization (城镇化), affordable housing, employment, food security, public health care, clean energy technology, and the reduction of bureaucratic barriers for private sector development.

In particular, Li has frequently called for “mass entrepreneurship and innovation” (大众创业, 万众创新). This policy has been credited with China’s technological development over the past few years, as evidenced by the vitality of China’s e-commerce and e-payment systems. His township-centered urbanization, however, was regarded by Xi’s economic team as neither desirable (due to its resulting inefficiency of resources and widespread pollution) nor feasible (because young people are less interested in staying at small towns) and thus was largely replaced by a development strategy for large urban clusters.

At a time when Xi enjoys tremendous individual power, Li can potentially be viewed as a balancing force—though not an impressive one thus far—within the political establishment.

Compiled by Cheng Li and the staff of the John L. Thornton China Center at BrookingsNotes

- “Sent-down youth” (插队知青) refers to young, educated urbanites who left their home cities to serve as manual laborers in the countryside during the Cultural Revolution.

- Li Meng, “Li Keqiang and the class of ’77 at the Department of Law at Peking University” [Li Keqiang suozai de beida falüxi 77 ji], Democracy and Law [Minzhu yu fazhi], October 26, 2009.

- For more information about Li Keqiang’s family background and his early experiences, see Hong Qing 洪清, “He will be China’s Top Manager: The Biography of Li Keqiang” [他将是中国大管家—李克强传] (New York: Mirror Books, 2010).

- Jeremy Page, Bob Davis, and Lingling Wei, “Xi Weakens Role of Beijing’s No. 2,” Wall Street Journal, December 20, 2013.

Download Profile as PDF

Download Profile as PDF

Han Zheng 韩正

- Born 1954

- Executive Vice Premier of the State Council (2018–present)

- Member of the Politburo Standing Committee (PSC) (2017–present)

- Deputy Head of the Central Leading Group for Comprehensively Deepening Reforms (2018–present)

- Head of the Three Gorges Project Construction Committee (2018–present)

- Head of the South-North Water Diversion Construction Project Committee (2018–present)

- Head of the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Joint Development Leading Group (2018–present)

- Head of the Central Leading Group for “Belt and Road Initiative” Construction (2018–present)

- Member of the Politburo (2012–present)

- Full member of the Central Committee of the CCP (2002–present)

Personal and Professional Background

Han Zheng was born in April 1954 in Shanghai. His ancestral home is Cixi City, Zhejiang Province. Han joined the CCP in 1979. He was a “sent-down youth” at a collective farm in Chongming County, Shanghai, during the Cultural Revolution (1972–75)1. Han attended a two-year college program at Fudan University in Shanghai (1983–85), completed his undergraduate degree (via part-time studies) in politics at East China Normal University in Shanghai (1985–87), and graduated with a master’s in international political economy from East China Normal University (1994–96).

Han spent much of his early career working at the grassroots level. Han worked in the warehouse of a lifting installation company in Shanghai, and as a clerk in the supply and marketing division of the same company. Han then served as deputy secretary of the Chinese Communist Youth League (CCYL) (1975–80) and as a clerk of the Shanghai Chemical Equipment Industry Co., Ltd (1980–82). Han was then made secretary of the CCYL committee of the Chemical Industry Bureau of the Shanghai Municipal Government (1982–86), deputy party secretary of the Shanghai School of Chemical Engineering (1986–87), party secretary and deputy director of Shanghai No. 6 Rubber Shoes Factory (1987–88), and party secretary and deputy director of the Dazhonghua Rubber Plant in Shanghai (1988–90).

Subsequently, Han served as deputy secretary (1990–91) and secretary (1991–92) of the CCYL Shanghai Municipal Committee. He was later appointed deputy party secretary and head of the Luwan District in Shanghai (1992–95) and was eventually promoted to deputy secretary-general (chief of staff) of the Shanghai municipal government, in addition to director of the City Planning Commission and director of the Securities Management Office (1995–97). He became a member of the Standing Committee of the Shanghai Municipal Party Committee while continuing to work as deputy secretary-general (1997–98).

Han continued to advance his career in Shanghai, serving as vice-mayor (1998–2003), deputy party secretary (2002–12), mayor (2003–12), acting party secretary (2007), and finally party secretary (2012–17). He also served as deputy head of the 2010 Shanghai World Expo Organizing Committee and head of the Executive Committee (2004–11). He was first elected to the Central Committee as a full member at the 16th Party Congress in 2002.

Family and Patron-Client Ties

Prior to the 19th Party Congress in the fall of 2017, Han spent his entire career working in Shanghai. It was during his time in Shanghai that Han met five of his patron-mentors, namely Huang Ju, Wu Bangguo, Zhu Rongji, Zeng Qinghong, and Yu Zhengsheng, all of whom later served as members of the Politburo Standing Committee2. Han has been widely recognized as a member of the Jiang Zemin-Zeng Qinghong “Shanghai Gang.” Although Han served as a top CCYL official in Shanghai, his promotions have been more closely aligned with Jiang’s Shanghai Gang than with the Hu Jintao-Li Keqiang CCYL faction3. He also developed good relations with Xi Jinping when Han served as Xi’s deputy in Shanghai in 2007, before Xi moved to Beijing to serve as a member of the Politburo Standing Committee. Han appears to have earned Xi’s support, obtaining a Politburo seat after Xi became general secretary of the CCP in 2012.

Not much information is available about Han Zheng’s family. According to an unverified source, Han Zheng’s wife, Wan Ming, previously served as vice-chair of the Shanghai Charity Foundation. The couple has one daughter.

Political Prospects and Policy Preferences

Having served for two decades as a top administrator of China’s pacesetting city, Shanghai, Han Zheng emerged from the 19th Party Congress as a top economic decision-maker in national leadership. Han’s reputation as a competent, seasoned financial and economic technocrat, as well as his market-friendly policy orientation in cosmopolitan Shanghai, has generally been well received in business communities both in China and abroad. According to the current CCP regulations and norms, Han will most likely serve only a single term in the Politburo Standing Committee and then retire in 2022–23. If, for some reason, Li Keqiang steps down from his position as premier of the State Council before the end of his term, Han may be a leading candidate for that position.

Compiled by Cheng Li and the staff of the John L. Thornton China Center at BrookingsNotes

- “Sent-down youth” (插队知青) refers to young, educated urbanites who left their home cities to serve as manual laborers in the countryside during the Cultural Revolution.

- In 1988, for example, Zhu Rongji, then mayor of Shanghai, visited the city’s Dazhonghua Rubber Plant, where Han Zheng was employed. During the visit, Zhu lauded Han’s work. See Xu Yanyan 许燕燕, “Han Zheng recalls Zhu Rongji’s visit to factory” [韩正回忆朱镕基下工厂], Yicai Web [第一财经网], August 14, 2013, http://www.yicai.com/news/2939288.html.

- Cheng Li, Chinese Politics in the Xi Jinping Era: Reassessing Collective Leadership (Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution Press, 2016), p. 281.

Download Profile as PDF

Download Profile as PDF

Sun Chunlan 孙春兰

- Born 1950

- Vice Premier of the State Council (2018–present)

- Member of the Politburo (2012–present)

- Deputy Head of the Central Leading Group for United Front Work (2015–present)

- Head of the State Council Leading Group of Deepening Medical and Health System Reform (2018–present)

- Deputy Head of the Central Coordination Group for Hong Kong and Macao Affairs (2016–present)

- Full member of the CCP Central Committee (2007–present)

Personal and Professional Background

Sun Chunlan was born on May 24, 1950, in Raoyang County, Hebei Province. She joined the CCP in 1973. She received a technical education from the Anshan Institute of Iron and Steel Technology in Anshan City, Liaoning Province (1965–69)1. She later studied economic management in the Department of Economics at Liaoning University in Shenyang, Liaoning Province (via correspondence studies, 1981–84); participated in a program in economic management at the Liaoning Party School in Shenyang City, Liaoning Province (via correspondence studies, 1989–91); and attended a one-year training program at the Central Party School in Beijing (1992–93). Sun also completed a master’s program in management at Liaoning University in Shenyang (via part-time studies, 1992–95) and a master’s program in politics at the Central Party School (via part-time studies, 2000–03).

Sun began her career as a worker in a watch factory in Anshan (1969) and, eventually, became a party official in the same factory (1971–74). She served as secretary of the Chinese Communist Youth League (CCYL) of the Light Industry Bureau of Anshan City (1974–77), and served as a manager and party official of the Anshan Textile Factory (1977–88). She was head of the Women’s Association of Anshan City (1988–91), deputy head of the Workers’ Union of Liaoning Province (1991–93), head of the Women’s Association of Liaoning (1993–94), head of the Workers’ Union of Liaoning (1994–97), and deputy party secretary of Liaoning (1997–2005). She also served as party secretary of Dalian, Liaoning (2001–05), and as first secretary of the All-China Federation of Trade Unions (ACFTU) (2005–09). She then served as party secretary of Fujian (2009–12) and party secretary of Tianjin (2012–14). Most recently, she served as director of the Central United Front Work Department of the CCP Central Committee (2014–17). She was first elected to the Central Committee as an alternate member at the 15th Party Congress in 1997.

Family and Patron-Client Ties

Sun Chunlan comes from a humble background. Her father was a factory worker. No further information is available on Sun’s family. Sun is widely considered a protégé of Hu Jintao, but it is unclear where and when Sun established her patron-client relationship with Hu. Their political connection likely began or was consolidated during her studies at the Central Party School in the early 1990s, when Hu served as president of the school2. According to some Chinese observers, Sun effectively constrained the power and influence of Bo Xilai in Dalian after she took over as the city’s party chief from 2001 to 2005.3

Policy Preferences and Political Prospects

Like her mentor Hu Jintao, Sun is known for her keen interest in promoting a harmonious society, supporting policy initiatives for affordable housing, social welfare for low-income families, and poverty reduction.

Sun is the only woman leader whose age allowed her to stay on the Politburo for another term, through the 19th Party Congress. Moreover, Sun Chunlan has some political leverage in promoting policy initiatives among her peers in the Politburo. First, her leadership experience running an important province (Fujian) and two major cities (Tianjin and Dalian), as well as her tenure as first secretary of the All-China Federation of Trade Unions and director of the Central United Front Work Department of the CCP Central Committee, have prepared her for even more important posts in the national leadership. Second, her low-profile personality and her demonstrated tenacity and political acumen, most notable in removing Bo Xilai’s protégés in Dalian even before Bo’s downfall, are indicative of her potential for leadership and political nerve. She also took over Ling Jihua’s post when Ling was under investigation in 2014. Given her age, Sun will likely retire in the next leadership transition in 2022-23.

Compiled by Cheng Li and the staff of the John L. Thornton China Center at BrookingsNotes

- In 2002, the school was renamed the Anshan Institute of Science and Technology. Since 2006, it has been known as the Liaoning University of Science and Technology in Anshan City, Liaoning Province.

- Hu Min, Hu Jintao’s Five Golden Flowers (Hong Kong: Beiyunhe Press, 2012), pp. 159–63.

- Ibid.

- Mandy Zuo, “Party’s number two woman Sun Chunlan named chief of Tianjin,” South China Morning Post, November 22, 2012, (http://scmp.com/news/china/article/1087831/partys-number-two-woman-sun-chunlan-named-chief-tianjin).

Download Profile as PDF

Download Profile as PDF

Hu Chunhua 胡春华

- Born 1963

- Vice Premier of the State Council (2018–present)

- Member of the Politburo (2012–present)

- Deputy Head of the Central Leading Group for “Belt and Road Initiative” Construction (2018–present)

- Full member of the Central Committee of the CCP (2007–present)

Personal and Professional Background

Hu Chunhua was born in April 1963 in Wufeng County, Hubei Province. Hu joined the CCP in 1983. He received a bachelor’s degree in Chinese literature from Peking University (1979–83) and a master’s degree (via part-time studies) in world economics from the Central Party School (1996–99).

After graduating from Peking University, Hu went to Tibet, where he worked as a clerk at the Organization Department in the CCP Committee of Tibet (1983–84), as an official at the newspaper Tibet Youth Daily (1984–85), and as an official at the Tibet Hotel (1985–87). Hu advanced his political career largely through the Chinese Communist Youth League (CCYL). He served as deputy secretary (1987–92) and secretary (1992–95) of the CCYL in Tibet. He also worked as deputy head of Linzhi Prefecture, Tibet (1992), and as deputy party secretary and head of Shannan Prefecture, Tibet (1995–97). He then served as a member of the Secretariat of the CCYL National Committee and vice-chairman of China’s Youth Federation (1997–2001). In July 2001, Hu returned to Tibet, where he served as secretary-general (chief of staff) of the CCP Committee of Tibet (2001–03) and deputy party secretary and executive vice-governor of Tibet (2003–06). He then served as the first secretary of the Secretariat of the CCYL Central Committee (2006–08). After that, Hu served as governor and deputy party secretary of Hebei Province (2008–09). In 2009, he was transferred to Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, where he served as party secretary (2009–12) and chairman of the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Regional People’s Congress (2010–12). He served as party secretary of Guangdong (2012–17). Hu was first elected to the Central Committee as a full member at the 17th Party Congress in 2007.

Family and Patron-Client Ties

Hu Chunhua was born into a family of very humble means. His parents were farmers in a poor and remote village within an ethnic minority autonomous county in Hubei Province. Hu Chunhua has six siblings. He was the first person from his county to attend Peking University. Hu volunteered to work in Tibet after graduation, where he established his patron-mentor relationship with Hu Jintao, who was then serving as party secretary (1988–92). Hu Chunhua has been widely characterized as “a carbon copy of Hu Jintao” and has even been called “little Hu.”1 Both come from humble family backgrounds, served as student leaders during their college years, advanced their political careers primarily through the CCYL, worked in arduous environments like Tibet, served as provincial party secretaries at a relatively young age, and have low-profile personalities.

Not much information is available regarding Hu Chunhua’s family. He and his wife were married in Tibet and have one daughter.

Policy Preferences and Political Prospects

Hu Chunhua was selected as a Politburo member in 2012 and is considered a front-runner of the so-called sixth generation leadership. Some analysts have viewed Hu’s Politburo membership as a reflection of Deng Xiaoping’s political design for a “grandpa-designated successor” (隔代指定接班人).

This refers to the pattern whereby Deng designated Hu Jintao, Jiang Zemin designated Xi Jinping, and Hu Jintao designated Hu Chunhua to be the top leaders of the succeeding generations2. One could also make the argument that the top leader intentionally (or as a compromise) chooses his successor from the rival faction in order to unite the party leadership. In other words, the party boss selects a “team of rivals” (政敌团队) in order to consolidate power.3

Therefore, Chinese public expectations in the lead-up to the 19th Party Congress were that Hu Chunhua would ascend to the 19th Politburo Standing Committee, which presented a serious challenge for Xi. The fact that Xi did not allow any six-generation leader to enter the PSC and the recent abolishment of the term limit for the PRC presidency indicates that Hu’s chances of becoming a designated successor have diminished. One could reasonably make the point that Xi has prevented Hu Chunhua from rising to the pinnacle of power.

Yet, as the youngest vice premier of the State Council and a two-time Politburo member, Hu is still the highest-ranking leader of the sixth generation. Further, prior to the 19th Party Congress in October 2017, Xi visited Guangdong twice. During these visits, Xi affirmed the good work carried out under Hu Chunhua’s leadership, especially in the areas of supply-side economic reform, technological innovation, and social stability4. Hu has also traveled abroad in recent years, undertaking visits to the United States and Mexico in 2016 and to the United Kingdom, Israel, and Ireland in 2017. In conjunction with his frequent meetings with foreign leaders in Guangdong, these trips abroad have helped to broaden Hu’s international experience.

Compiled by Cheng Li and the staff of the John L. Thornton China Center at BrookingsNotes

- For more discussion about Hu Chunhua’s patron-client ties with Hu Jintao, see Ren Huayi, The Sixth Generation: The CCP’s Last Generation of Successors [第六代:中共末代接班群] (New York: Mirror Books, 2010), and Ke Wei, The Rising Stars of the CCP’s Sixth Generation [中共第六代明星传] (Hong Kong: New Culture Press, 2010).

- Zhang Ping, “The sixth generation of leaders in the Chinese Communist Party was born out of speculations,” Deutsche Welle, November 21, 2012.

- Cheng Li, “China’s Team of Rivals,” Foreign Policy, March/April 2009, pp. 88–93.

- Nanfang ribao [南方日报], April 12, 2017.

Download Profile as PDF

Download Profile as PDF

Liu He 刘鹤

- Born 1952

- Vice Premier of the State Council (2018–present)

- Member of the Politburo (2017–present)

- Head of the Financial Stability and Development Committee of the State Council (2018–present)

- Head of the Air Traffic Control Committee of the State Council and the Central Military Commission (2018–present)

- Head of the Production Safety Committee of the State Council (2018–present)

- Head of the Leading Group for Building an Advanced Manufacturing Industry (2018–present)

- Head of the Leading Group for the Promotion of Small and Medium-sized Enterprises of the State Council (2018–present)

- Director of the General Office of the Central Leading Group for Financial and Economic Work of the CCP Central Committee (2013–present)

- Vice Minister and Deputy Party Secretary of the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) (2013–present)

- Full member of the Central Committee of the CCP (2012–present)

Personal and Professional Background

Liu He was born on January 25, 1952, in Beijing. His ancestral home is Changli County, Hebei Province. Liu joined the CCP in December 1976. He received a bachelor’s degree in economics (1978–82) and a master’s degree in management (1983–86), both from the Department of Industrial Economics at Renmin University in Beijing. He received an MBA from the School of Business Administration at Seton Hall University (1992–93) and an MPA from the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University (1994–95), where he was a Mason Research Fellow. Liu was a founder and convener of the Chinese Economists 50 Forum1. He serves as a professor of economics at Renmin University, Peking University, Tsinghua University, and the Beijing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics.

Liu began his career as a “sent-down youth” at an agricultural commune in Jilin Province (1969–70)2. He also served as a soldier in the 38th Group Army of the PLA (1970–73). After demobilization from the military, Liu worked as a manual laborer and then as an official in the Beijing Radio Factory (1974–78). He later taught at Renmin University as an instructor (1986–87). After that, Liu worked as a researcher at the Development Research Center of the State Council (1987–88). He then served as deputy director of the Research Office and then deputy director of the Industrial Policy and Long-term Planning Department in the State Planning Commission (1988–98). Liu was subsequently promoted to director of the State Information Center (1998–2001). He then served as deputy director of the State Council Information Office, where he was in charge of e-commerce and international cooperation (2001–03).

Liu served as deputy director of the Central Leading Group for Financial and Economic Work, where he was responsible for overseeing macro-economic policy-planning and drafting speeches for CCP General Secretary Hu Jintao to deliver at annual CCP national conferences on economic affairs (2003–11). Liu then served as party secretary and deputy director of the Development Research Center of the State Council (2011–13). He served as vice-minister and deputy party secretary of the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) (2013–18). He was first elected to the Central Committee as a full member at the 18th Party Congress in 2012.

Family and Patron-Client Ties

Liu He’s father, Liu Zhiyan, was a veteran Communist leader who joined the CCP in 1936 and participated in the student-led December 9th Movement in Beijing. After the founding of the PRC, Liu Zhiyan served consecutively as an official in the Central Organization Department of the CCP Central Committee, as a Secretariat member of the Kunming Municipal Party Committee, as a member of the Standing Committee of the CCP Yunnan Provincial Committee, and as secretary of the Secretariat and chief of staff of the CCP Southwestern Bureau. Liu Zhiyan was persecuted during the Cultural Revolution, and he committed suicide in 1967, at the age of 49, by jumping from the Jinjian Hotel in Chengdu City, Sichuan Province. He was Liu Zhiyan’s only child from his first marriage, which ended in divorce. Liu Zhiyan’s second marriage resulted in one son and one daughter. The daughter, Liu He’s half-sister, married Gong Zheng, the current governor of Shandong Province.

Liu He is one of Xi Jinping’s most trusted confidants3. Their friendship stems from their childhoods in Beijing. Some foreign and Chinese media outlets have reported that Xi Jinping and Liu He attended the same middle school4. In fact, Xi attended the Bayi School and Beijing No. 25 School, while Liu went to Beijing No. 101 School in the same district. It is likely that their friendship developed through growing up together in the same neighborhood.

As an accomplished financial expert as well as an effective communicator in both Chinese and English, Liu He has proven to be a great asset to Xi. Liu He has also been recognized for his humble demeanor. He has responded to praise of his work by stating that it is inappropriate to emphasize any one individual’s contributions to China’s economic policy. Unsurprisingly, when Xi Jinping became general secretary of the party, he promoted Liu He to vice-minister of the NDRC and office director of the Central Leading Group for Financial and Economic Work, in which capacity he serves as Xi’s chief economic strategist.

Policy Preferences and Political Prospects

The author of five books and over 200 articles, Liu He focuses his research on five broad areas: the relationship between economic development and changes in industrial structure in China; macroeconomic theory; corporate governance and property rights; the new economy and the information industry; and the reform of Chinese SOEs. Liu He has contributed significantly to the new economic paradigms and concepts outlined in Xi Jinping’s first term, such as the “economic new normal” and “supply-side reform.” His economic outlook is remarkably liberal. Liu served as a chief drafter of the communiqué at the Third Plenum of the 18th National Party Congress, which claimed to be “version 2.0” of China’s market development.5

Liu He is widely considered to be an adviser rather than a policymaker. However, Liu’s career path, especially over the past two decades, has closely mirrored that of former vice-premier and Politburo member Zeng Peiyan6. As vice premier in charge of China’s finance and economic structural reforms, Liu plays a key role in implementing Xi’s economic agenda, including that of innovation-driven and environment-sensitive urbanization, prevention of financial crisis, and poverty alleviation. As Liu He articulated at the Davos World Economic Forum in 2018, active participation in economic globalization and the deepening of China’s economic reform and openness have remained central to the country’s long-standing economic outlook. Given his age, Liu will most likely serve only a single term in the Politburo.

Compiled by Cheng Li and the staff of the John L. Thornton China Center at BrookingsNotes

- The Forum consists of the country’s most influential economists and financial technocrats, including the current governor of the People’s Bank, Zhou Xiaochuan; executive vice-governor Yi Gang; and former minister of finance, Lou Jiwei. The mission of the Forum is to provide policy recommendations to the government on major economic issues. For more information, see http://www.50forum.org.cn/home/article/jianjie.html.

- “Sent-down youth” (插队知青) refers to young, educated urbanites who left their home cities to serve as manual laborers in the countryside during the Cultural Revolution.

- In the fall of 2013, Xi introduced Liu He to the U.S. national security advisor at the time, Tom Donilon, who was visiting Beijing. Xi said, “This is Liu He. He is very important to me.” Quoted from Bob Davis, “Meeting Liu He, Xi Jinping’s Choice to Fix a Faltering Chinese Economy,” Wall Street Journal, October 6, 2013.

- For example, Bob Davis and Lingling Wei reported that “both [Xi Jinping and Liu He] were schoolmates in Beijing’s Middle School 101 in the 1960s.” Ibid. Also see Wu Ming, “China’s new leader: Biography of Xi Jinping” [中国新领袖:习近平传], enlarged new edition (Hong Kong: 文化艺术出版社, 2010), p. 572.

- Cheng Li, Chinese Politics in the Xi Jinping Era: Reassessing Collective Leadership (Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution Press, 2016), p. 324.

- Ibid., pp. 362–63.

Author

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).