US rental housing markets are diverse, decentralized, and financially stressed

Editor’s note: In case you missed it, watch an event held on April 21 discussing lessons from around the world related to policies to support stable, affordable rental housing.

The U.S. rental housing market is large and diverse, serving 44 million households in all parts of the country. Renter households are younger, less affluent, and more racially diverse than homeowner households. Historically, U.S. housing policies have substantially favored homeowners over renters, both through federal tax policies and local land use regulations. The COVID-19 pandemic and economic crisis have exposed the limited policy protections for renters—notably, the lack of financial support for low-income households and a patchwork of state and local legal protections.

Overview of renter households and rental housing

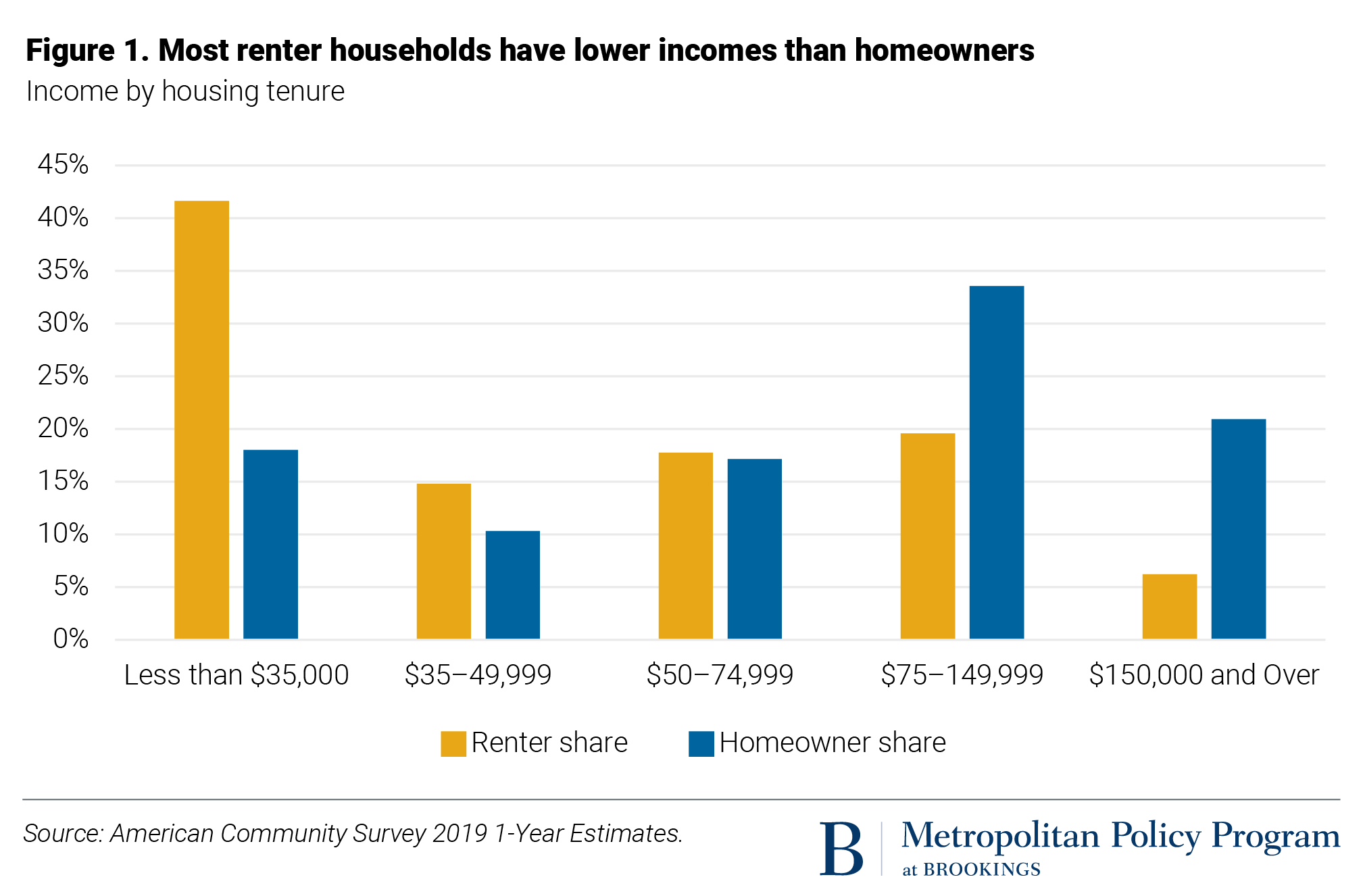

Renter households are younger, less affluent, and more racially diverse than homeowners. For most of the past 50 years, roughly one-third of U.S. households have rented their homes. Rentership rates rose during the Great Recession, and today remain relatively high, at 35.6%. Rentership rates have increased among some groups that have traditionally been more likely to own, including higher-income households and middle-aged adults. Homeowners are more affluent than renters: The median income of renters was $42,479 in 2019, which is roughly half that of homeowners. Over 40% of renter households earn less than $35,000 per year; this group faces the greatest difficulty in affording market-rate housing.

Renters are also more racially diverse and younger than homeowners. Black, Latino or Hispanic, and Asian American households are disproportionately likely to rent their homes. In 2018, 48% of renters were nonwhite, compared to27% of homeowners. The median renter was15 years younger than the median homeowner in 2018. Renter households are also smaller on average than owner households: About 37% of renter households are single-person households, compared to 28% of homeowner households. The number of renter households with children has increased in recent years.

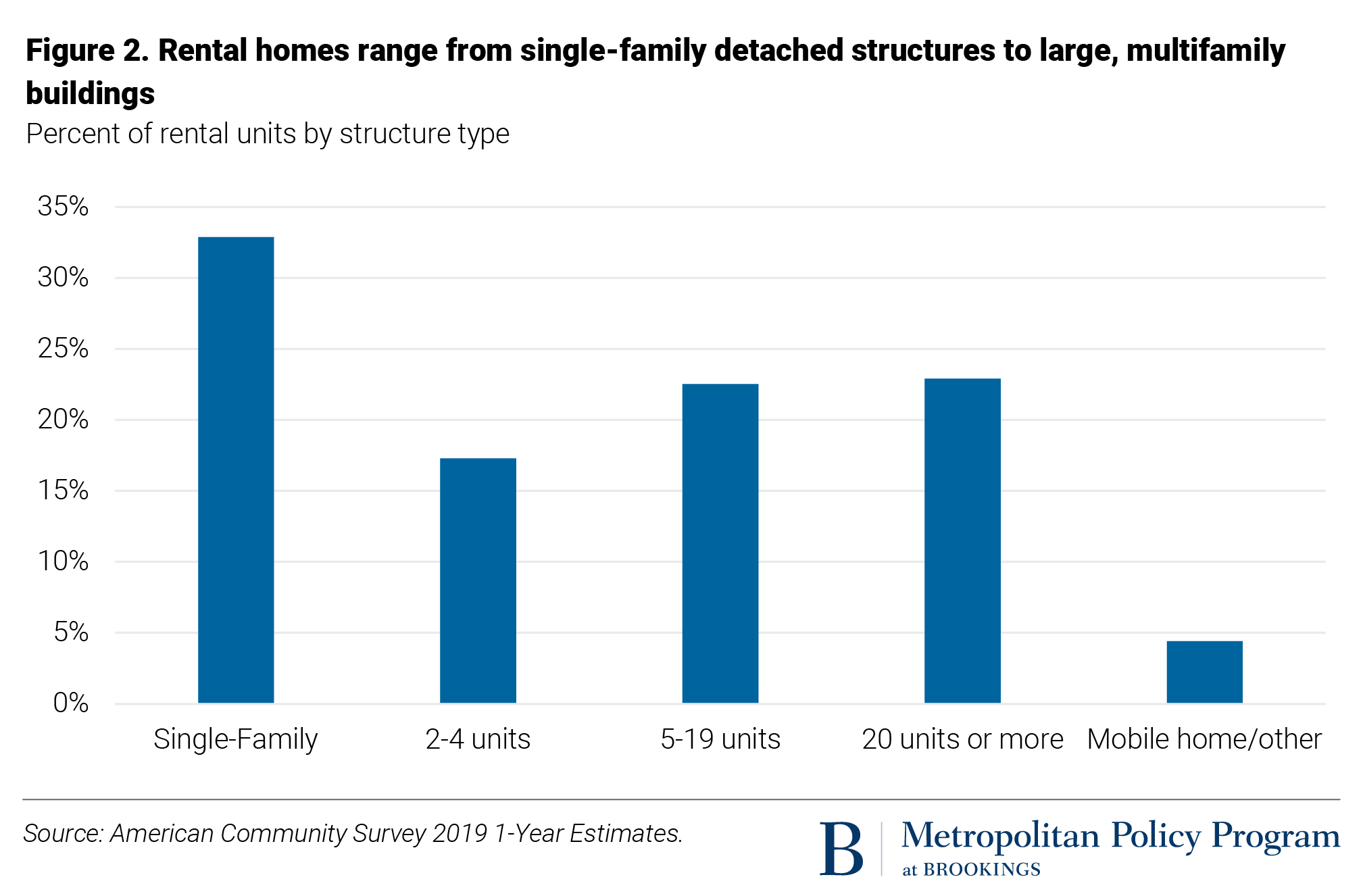

The rental housing stock is similarly diverse, with substantial variation in structure type, building size, quality, and rent level across regions of the country. Rental properties range from single-family detached homes to large, multifamily buildings (Figure 2). Nearly half of rental homes are in small buildings (one to four units), while 23% of rental units are in buildings with 20 or more units. Rental housing is a larger share of the housing stock in urban areas.

The Northeast and Midwest regions have a somewhat older housing stock (which typically has more maintenance problems) than the South and West. Manufactured housing—homes that are constructed in a factory then placed on a steel chassis—form a larger share of rental housing in rural areas, especially in the South. These homes are an important source of lower-cost, unsubsidized housing.

Nationally, only a small fraction of rental homes have severe housing inadequacies, such as problems related to heating, plumbing, and electrical systems. In recent years, tight restrictions on new construction have encouraged investors to renovate and upgrade older apartment buildings, especially in desirable locations. This process prevents these apartments “filtering” down and becoming affordable to lower-income households, exacerbating affordability problems.

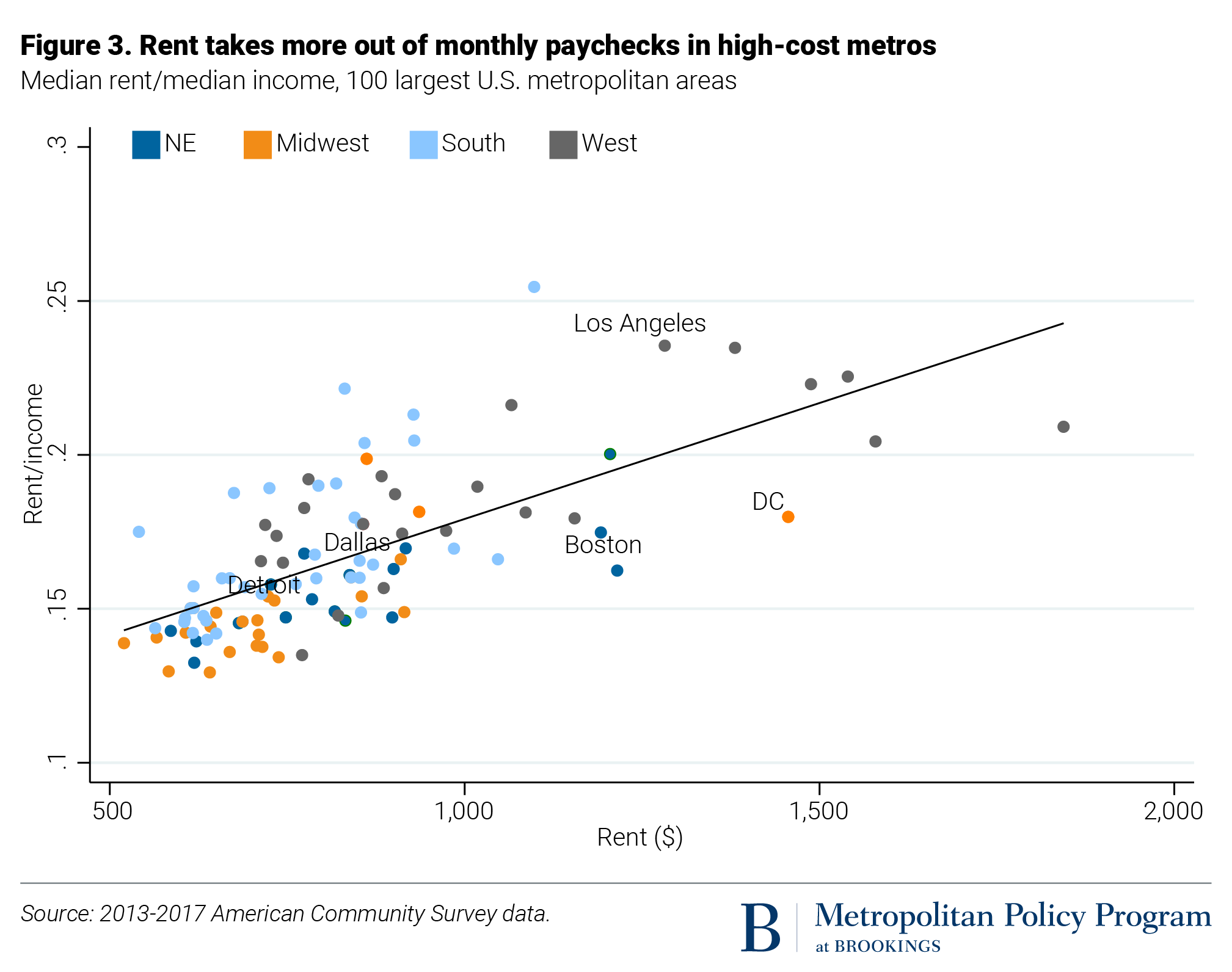

The affordability of rental housing, both in rent levels and relative to household income, varies widely across geographic areas. Median monthly rents are highest in large metro areas on the West Coast, and generally lower in the Midwest and South (Figure 3). Incomes tend to be higher in expensive regions, but do not completely compensate for higher rent levels.

Institutional and policy environment of rental housing

Private sector firms play the largest role in developing and managing rental housing

Most rental housing in the U.S. is developed, financed, and owned by a diverse group of private, for-profit companies. Government entities such as local public housing authorities own a relatively small share of rental housing. Even in the below-market rental sector that serves low-income renters, most properties are developed and owned either by not-for-profit organizations or private, for-profit landlords.

Private landlords run the gamut from individual investors (one person or family) to large institutional investors, such as insurance companies, real estate investment trusts (REITs), private equity firms, and other corporate entities. Individual investors own a majority of small rental properties (one- to four-unit buildings), while institutional investors own most large (50-plus units) rental properties. Since the Great Recession, institutional investors have acquired an increasing share of the single-family rental market. Ownership of rental housing is not highly concentrated nationally, but exhibits some concentration within local geographic areas. The real estate industry has consolidated somewhat since the Great Recession, with a few large firms making up a larger share of both development and property ownership.

Financing to develop and acquire rental housing is available from a range of sources—primarily commercial banks, insurance companies, and specialized financial service companies. In general, large properties and those developed or owned by institutional investors tend to have more complex financing arrangements. Over the past several years, nonbank financial institutions have grown their market share of commercial real estate lending. The U.S. has an active market in commercial mortgage-backed securities (CMBS), in which loans backed by apartment buildings are bundled and traded as financial instruments.

The US provides more generous housing subsidies to homeowners than to renters

Historically, the U.S. has devoted more resources to subsidizing homeowners than renters, despite the fact that renter households are on average less affluent. Federal tax policy includes several subsidies for homeowners—notably the mortgage interest deduction (MID), which allows homeowners to deduct the value of interest paid on their mortgage from their income subject to federal taxes. Most of the benefits from the MID accrue to high-income households, especially after changes made in the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act.

Rental subsidies in the U.S. are targeted at low-income households. Unlike benefits administered through the tax code, the amount of rental subsidies depends on annual appropriations from Congress. Only one in four eligible low-income renter households receives any federal rental assistance.

Three programs make up the bulk of federal rental assistance: household-based vouchers, public housing, and the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) program. Nearly 2.3 million low-income families receive vouchers, which they can use to rent homes owned and operated by private landlords. Voucher holders pay 30% of their monthly income toward housing costs, with the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) covering the remainder. The U.S. has approximately 1.2 million public housing units owned and operated by local public housing authorities, which receive operating subsidies from HUD. The U.S. largely stopped building public housing by 1990, and has since demolished or redeveloped more than 300,000 units.

The primary source of funds for new construction of below-market rental housing is the LIHTC program, which allocates federal income tax credits to private and nonprofit developers. These credits are sold to private investors, raising equity for income-restricted rental housing. Over 2 million apartments have been constructed or preserved through LIHTC.

Some state and local governments also fund their own rental subsidies, but the amount of funding through these programs is much smaller than federal subsidies.

Developing new rental housing faces legal and political barriers

Over the past 40 years, the legal and political environments have become increasingly hostile to developing new rental housing. Land use planning and development permitting are primarily the responsibility of local governments. States exercise some authority over land use regulation, while the federal government has quite limited powers. Local governments use a wide range of tools to regulate new housing development, particularly zoning laws that specify where structures of different types and sizes may be built. Zoning generally sets rules by structure type (multifamily versus single-family) rather than housing tenure (rental versus owner-occupied). Nearly all local governments have zoning laws that are more favorable to single-family homes than apartments and other high-density structures. Many affluent communities ban development of multifamily buildings on the majority of land. Where permitted, apartments are often constrained by strict size rules such as maximum building height or caps on the number of homes per acre of land. Since the 1970s, procedural barriers to apartments have become widespread, such as requiring extensive community reviews and discretionary approvals.

The legal environment around rental housing varies widely across the US

State governments establish the legal framework around rental housing, leading to wide variation across states in renter protections. The landlord-tenant relationship is generally based in property law, with both parties being assigned rights and responsibilities set out in a lease. One-year leases are standard across most of the U.S. Landlords may evict a tenant from their property for violating the terms of the lease agreement; the most common cause of evictions is failure to pay rent. The eviction process varies widely across states and cities. Key provisions include the length of time between an initial filing and completed eviction, and whether tenants have the right to legal counsel. Most evictions take place in civil court.

Federal law provides few explicit renter protections. The Fair Housing Act prohibits discrimination in all housing-related transactions on the basis of race, gender, family status, religion, ethnicity, national origin, or disability. The U.S. does not have a national “right to housing,” meaning there is no affirmative obligation for the public sector to provide housing to everyone.

Rent regulation of privately owned rental properties (e.g., caps on annual increases on rent) is relatively scarce, although it has drawn increasing attention in recent years. Some large cities—notably New York City, San Francisco, and Washington, D.C.—have local rent control programs. But more than half of U.S. states have laws that preempt local governments from adopting rent control. Tenants’ unions exist in some states and localities, allowing groups of tenants to engage in collective bargaining with landlords and state and local governments.

Key challenges facing rental housing markets include affordability and limits on development

The most important challenges facing U.S. rental housing markets over the past decade are affordability for low-income households, restrictions on new development, and—in some parts of the country—poor-quality housing and overcrowding.

Low-income renters everywhere in the U.S. face high housing cost burdens. HUD defines nearly 20.8 million Americans as “cost-burdened,” meaning that they spend more than 30% of their income on housing and utilities. Some 25% of renters are severely cost-burdened, spending more than 50% of income on housing.

Excessively strict land use regulations are limiting the supply of rental housing and increasing rents, particularly in large metropolitan areas along the West Coast and the Northeast Corridor. Local zoning makes it illegal to build multifamily buildings (either owner- or renter-occupied) on most land in urban areas. The development process has become increasingly long, complex, and risky, which also adds to the cost of finished housing.

Poor-quality housing is a concern in some parts of the U.S., particularly in older industrial cities in the Northeast and Midwest, as well as rural areas with declining populations. Largely this is due to old housing stock with deferred maintenance problems.

The COVID-19 pandemic has drawn renewed attention to overcrowded housing. Although crowding is not a widespread problem among U.S. renters, families with children living in high-cost metro areas are most at risk. Immigrant communities tend to have higher rates of crowded housing.

The COVID-19 pandemic has hit renter households especially hard

The COVID-19 pandemic has inflicted the greatest health and economic damage on low-wage workers, including Black and Latino or Hispanic households. Thirty-nine percent of people who were working in February 2020 and had a household income below $40,000 reported a job loss in March 2020. Renters have consistently reported higher levels of housing insecurity than homeowner households. Nine million adult renters were behind on rent in November 2020. Renters of color were more likely to report housing insecurity, with 31% of Black renters experiencing hardship. Some large, expensive metro areas have seen declining rent levels, while smaller, more affordable cities have seen continued rent growth. Missed rent payments create greater financial stresses on small, nonprofessional landlords who own older, lower-rent properties.

Federal, state, and local policy interventions have provided temporary financial relief to renters through several channels. The federal CARES Act, passed in March 2020, expanded the amount of weekly unemployment insurance, including to workers normally excluded from these programs. Under the same legislation, the federal government distributed one-time stimulus checks of up to $1,200 to millions of Americans based on income and household size. Congress passed additional relief measures in December 2020 and March 2021, extending cash payments to households and assistance to state and local governments.

The pandemic has generated unprecedented federal attempts to regulate evictions. In September 2020, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued a temporary nationwide eviction moratorium through the end of December, based on the public health risks of displacing families. The CDC moratorium supplemented a patchwork of temporary state and local moratoriums adopted over the spring and summer.

State and local governments across the U.S. have also implemented rent relief programs, dispersing funding to support struggling renters. These programs, often funded by the federal CARES Act, vary widely in design. Most programs only had funds to serve a small fraction of eligible renters.

Conclusion

U.S. housing policies heavily favor homeowners over renters, from local restrictions on multifamily construction to federal tax policies. Low-income renters faced high housing cost burdens and housing instability even before the COVID-19 pandemic. The current economic crisis has disproportionately impacted low-wage, Black, and Latino or Hispanic renters, while public policy interventions exposed the lack of a permanent social safety net.