To protect Black women and save America from itself, elect Black women

This piece is adapted from a chapter in Perry’s new book “Know Your Price: Valuing Black Lives and Property in America’s Black Cities” (Brookings Press, 2020). It also draws from research conducted with the Higher Heights Leadership Fund.

One-hundred years ago, women finally gained the right to vote through the 19th Amendment. But it’s taken much longer for women—specifically, Black women—to be granted a seat at the cultural and political table of America.

Shirley Chisholm, the first Black woman elected to Congress (in 1968) and the first woman and African American to seek the nomination for president of the United States from one of the two major political parties (in 1972), famously said, “If they don’t give you a seat at the table, bring a folding chair.” A vanguard for women’s political leadership, Chisholm tactfully pushed for inclusion throughout the political process. But as her quote suggests, if conventional democratic processes fail, then you have to take matters into your own hands.

Recently, across the county, we have seen a new generation of Black political leaders do just that, while a legion of vital Black women voters pushes for long-neglected reforms. But Black women are still vastly underrepresented nationally among political candidates, making up only 2% of challengers to incumbents. If we truly want to create a more equitable America and solidify Black women’s seat at the table, we must bring Chisholm’s folding chair all the way to the White House—with a Black woman vice presidential candidate in 2020.

Representation matters to our political mental health. The fact that all but one president (and every vice president) in the history of the United States has been a white man would be completely unbelievable if the American psyche didn’t see leadership as equating to that one demographic. Today, Black women elected officials—Chisholm’s spiritual children—are not only representing people but also remedying the sick American psyche with every chair they bring to the table.

Black women’s rise should be America’s gain

In recent years, America has seen an unmistakable rise in the power of Black women—but that rise is still accompanied by the old burdens of racism and racial inequity.

Between 2009 and 2012, a higher proportion of Black women enrolled in college (9.7%) than Asian American women (8.7%), white women (7.1%), and even white men (6.1%).1 But the route to a postsecondary degree is still beset with harassment. Schools fail to intervene, contributing to girls’ insecurity. Nationally, Black girls accounted for 45% of all girls who were suspended and 42% of girls expelled from K-12 public schools between 2011 and 2012, the highest among all racial and ethnic groups, according to one University of Pennsylvania study.2

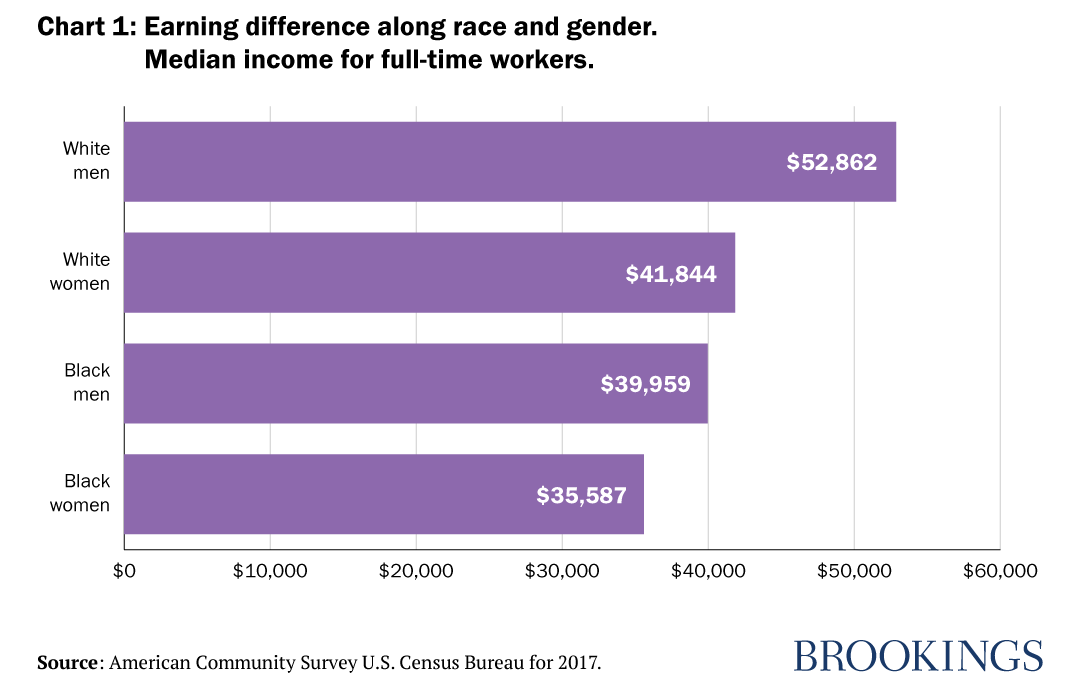

When girls do get out of school and into the workforce, they have to work more than 66 years to earn what a white man earns in 40. Black women have lower earnings than Black men, as well as white men and women. And while Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors, Opal Tometi, and other Black women are credited for popularizing the phrase “Black lives matter,” Black women’s maternal mortality rates are the highest in the world, largely because of racism in the health care system as well as physical violence inflicted upon Black women.

In a democracy, having the ability to legislate, run governments, and shape public policy is the primary way to gain protection, not only for Black women but the country as a whole. For Black lives to matter, Black women must be represented in legislative halls at every level in the United States. Fortunately, across the country, Black women are running for higher office—and winning.

Embracing Blackness to win votes

Black women are underrepresented among elected officials at local, state, and national levels of government. Black women are more likely to hold state house, state senate, and U.S. House of Representatives seats in places where the Black share of the voting-age population is greater. As a result, there is a higher concentration of Black women holding elected office in the Southeast U.S. There have been only two Black women elected to the U.S. Senate in the history of the country. The first was Carol Moseley Braun, who represented Illinois from 1993 to 1999, and the second is former 2020 presidential candidate Senator Kamala Harris of California.

Even though Black women are practically tied in percentage rates within race with white women in voter registration and turnout, they are more likely to be discouraged from running for office than white women and men as well as Black men.3 When Black women do run for office, they are less likely to receive the early dollars and endorsements that help establish campaigns. This is the structural racism and sexism that Black women must contend with. Because of these structural hurdles, Black women often lack access to candidate training to help them translate their experience into effective campaign strategies. Support for Black women on the campaign trail often comes not when they desperately need it, but when their impact can no longer be ignored.

The fact that all but one president (and every vice president) in the history of the United States has been a white man would be completely unbelievable if the American psyche didn’t see leadership as equating to that one demographic.

For generations, Black, mostly male, elected officials came from Black-majority districts. Black people voted other Black people, mostly men, into power. Before the 2018 midterm elections, there were 19 Black women and 30 Black men serving in Congress, as well as two nonvoting delegates. After the January 2019 swearing-in, there were 23 Black women in Congress—22 in the House— and 32 Black men. There is a majority of men despite the fact that there are many more Black women eligible to vote than Black men in Black-majority cities, underlining the underrepresentation of Black women in leadership positions.

However, there is a wave of Black women collectively forging new pathways into public office and breaking glass ceilings: mayors. Muriel Bowser of Washington, D.C., Sharon Weston Broome of Baton Rouge, LaToya Cantrell of New Orleans, and Keisha Lance Bottoms of Atlanta all won in places with significant Black populations.

In places where Black people are the racial minority, Black women politicians differ from their male predecessors by embracing their cultural heritage to attract non-Black voters.

“Can a Congresswoman wear her hair in braids?” Ayanna Pressley asked a crowded assembly hall during her victory speech on Election Day 2018. That night, Pressley became the first woman of color elected to Congress from the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, having earlier bested the 10-term Democratic incumbent, Michael Capuano, with her 17-point win in the primary.

Also in the 2018 midterms, Jahana Hayes won Connecticut’s 5th District; Lucy McBath claimed Georgia’s 6th, and Lauren Underwood won Illinois’ 14th. These are all Black women who saw victory by not shying away from their Blackness in white-majority places. Although Republican representative Mia Love of Utah lost her bid for reelection in 2018, she held her over-90% white district in Utah for two terms. At the municipal level, Vi Lyles’s victory in Charlotte in 2017 and London Breed in San Francisco in 2018—both Black women in white-majority cities—were predictive for Lori Lightfoot to win in Chicago in 2019, the largest city today to elect a Black mayor. Pressley and other Black women in public office are bucking the directive to sanitize one’s self and political agenda for fear of it being “too Black” to garner white votes.

America needs a Black women’s agenda

On the surface, the Democratic Party platform includes many of the items that cross over to a Black women’s agenda. However, there are points of emphasis and priority that distinguish a Black women’s agenda from a Democratic one. If Black women don’t raise key issues such as voting rights and maternal mortality, which are central to the health of our democracy and our people, it’s unlikely either political party will make them a serious priority.

The 2018 American Values Survey explores overall political attitudes and how increased diversity among elected officials could impact the country. On the question of what issues are the most important, Black women cited racial inequality as most critical, at 29%, followed by health care at 21%, and the growing gap between the rich and poor at 18%. The economy ranked as the fourth-most important issue, at 11%; if combined with the wealth gap, it would tie with racial inequality as the top issue for Black women.

Stacey Abrams may have lost her high-profile bid to become the governor of Georgia in 2018, but her campaign helped define an element of racial inequality worth pursuing in 2020: voter suppression. The winner of that gubernatorial race, former Georgia Secretary of State Brian Kemp, oversaw an election process that included voting roll purges and strict registration rules known to negatively impact minority voters.

Yet, on the American Values Survey, racial inequality ranked as the second-least important issue for white men and women (only lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender issues were lower). This means that ending voter suppression wasn’t likely to be a significant focus for either the Democratic or Republican parties; not until Black candidates campaigned and lobbied for it.

When we support and protect Black women, we begin to chip away the culture of physical violence that is normalized in policy in America.

Abrams’ political rise forced Democrats to raise voter suppression higher on their national agenda. In 2019, Rep. John Sarbanes (D-Md.) introduced the For the People Act, which includes provisions for voter registration modernization, that, if enacted, would make suppression more difficult. Abrams’ presence increases the likelihood that future candidates, including presidential ones, will bring voter suppression to the forefront of the party platform.

In April 2019, Representatives Alma Adams (D-N.C.) and Lauren Underwood (D-Ill.) put an unambiguous Black women’s issue on the national agenda. They created the first Black Maternal Health Caucus in an effort to reverse rising maternal mortality rates, which are significantly higher for Black women than white women. The caucus quickly gained 30 members, and is backed by Black maternal health practitioners, researchers, and advocates. Organizations such as Black Mamas Matter Alliance have been vigorously petitioning Congress to respond to the disproportionate number of Black women dying in childbirth. And now that representatives who are looking out for their interests are in the halls of power, those demands have a much greater likelihood of turning into policy.

Both parties are guilty of devaluating Black voters

The 2017 special election for the Alabama U.S. Senate seat vacated by former Attorney General Jeff Sessions accentuates how both major political parties devalue Black women and illustrates why they are underrepresented in Congress. High Black voter turnout in Alabama’s Black-majority cities, particularly among Black women, made the difference in the election, granting Democrat Doug Jones a historic victory over the controversial Republican Roy Moore. Moore is a twice-expelled judge who has been accused by multiple women of sexual harassment and assault when they were underage. Meanwhile, Jones endeared himself to the Black community by prosecuting two Ku Klux Klan members for the 1963 church bombing in Birmingham that killed four Black girls.

A whopping 68% of white voters supported Moore, who, upon being asked when was the last time America was “great,” replied, “I think it was great at the time when families were united—even though we had slavery—they cared for one another…Our families were strong, our country had a direction.”4

Jones beat Moore by only 1.5%, meaning he needed every vote he mustered. All but 4% of African-Americans who cast ballots voted for Jones, with Black residents accounting for roughly 30% of the Alabama electorate, according to Brookings analysis. Ninety-eight percent of Black women (17% of the electorate) cast ballots for Jones. Certainly, Jones needed each vote—but if Moore had courted a portion of the Black electorate, he could have won by a landslide.

Prior to the election, many Black voting rights activists criticized the Democratic Party’s last-minute get-out-the-vote effort in the state’s Black-majority districts. The New York Times reported that the Democratic Party cautioned against a late investment in advertising because “spending any money…would stir up the Republican base.” Meaning, the Democratic National Committee didn’t deploy resources into on-the-ground efforts, many of which are managed and staffed by Black women, in Black-majority areas—not exactly an astute assessment of value.

This shows that Black women have been saving the Democratic Party, which is not doing very much to uphold its promises to the Black community. There have always been charges from Democrats and Republicans that the Democratic Party takes advantage of—or devalues—the Black vote. From replacing Black leadership in the party to woo white suburban voters, to not putting financial support behind Black candidates, to not investing in the Black get-out-the-vote organizations in cities, the Democratic Party seemingly has not delivered policy to reciprocate the Black vote.5

For all intents and purposes, Black women carry the Black electorate in Black-majority cities. Meaning, they are the majority of voters and a greater share of the get-out-the-vote infrastructure there. Investments in Black women can yield sizable gains, as evidenced in the Alabama special election. Black men are present and voting at higher rates in recent years. However, Black men’s lower numbers in the electorate emphasize why Black women’s votes, voices, and leadership are critical. If they are not in positions of power, Black communities lose even more of our collective voice. Make no mistake: Black women value themselves and may very well walk away from the Democratic Party if their votes are taken for granted.

The future of Black women in power

Growing up in Black America during the 1970s, portraits of Martin Luther King, Jr., John F. Kennedy, and Jesus hung on many families’ walls. Today, the new trinity of Oprah, Beyoncé, and Michelle Obama could almost replace them. The success of movies like Girls Trip and Hidden Figures and the economic and cultural power of events like the Essence Music Festival in New Orleans are testaments to the flourishing strength of Black women. The might of Serena Williams, the political leadership of those behind the Women’s March, and the public intellectualism of Melissa Harris-Perry, Janet Mock, and Brittney Cooper, among others, equal or exceed their male and white counterparts.

Without question, Black women are standard-bearers who transcend race and class. But we should be clear: The growing educational and cultural influence of Black women doesn’t equal protection.

When we support and protect Black women, we begin to chip away the culture of physical violence that is normalized in policy in America. Suspensions and expulsions, physical violence, political underrepresentation, and lower pay all reflect a culture of American violence and devaluation. Black women’s experiences give them a unique perspective that can shed light on how racism and sexism stratify groups.

There can be no real, sustainable protection in a democracy without citizenship. Our quality of life and even our existence is tied to the assumptions of who is an official member of the country. Our lack of protection signals second-class status. Yet there is no more important power that can change that standing in the life of a citizen than the right to vote. Ending racism may solve many of Black people’s problems, but electing a Black woman to the highest offices in the land may save America from itself.

This piece is part of 19A: The Brookings Gender Equality Series. Learn more about the series and read published work »

- Fast Facts, Data Snapshot and Video Archive, National Center for Education Statistics, https://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/dailyarchive.asp.

- Edward J. Smith and Shaun R. Harper, “Disproportionate Impact Of K-12 School Suspension and Expulsion on Black Students in Southern States,” August 25, 2015, 92, https://www.issuelab.org/resource/disproportionate-impact-of-k-12-school-suspension-and-expulsion-on-black-students-in-southern-states.html.

- Kelly Dittmar, The Status of Black Women in American Politics, The Higher Heights Leadership Fund and the Center for American Women and Politics, Rutgers University, 2014, http://d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net/themes/51c5f2728ed5f02d1e000002/attachments/original/1404487580/Status-of-Black-Women-Final-Report.pdf?1404487580.

- Lisa Mascaro, “Roy Moore: America Was Great ‘When Families Were United—Even Though We Had Slavery,’” LAtimes.com, December 8, 2017, https://www.latimes.com/politics/washington/la-na-pol-essential-washington-updates-roy-moore-america-was-great-when-1512758057-htmlstory.html.

- Terry M. Neal and Thomas B. Edsall, “Democrats Fear Loss of Black Loyalty,” washingtonpost.com, August 3, 1998, https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/politics/campaigns/keyraces98/stories/keydem080398.htm