The President’s Advisors

As we mark the centennial of the 19th Amendment, we can note with pride the incredible strides that women have made in American politics—apart from securing the right to vote and participating more than their male counterparts, women have been consequential activists, won elected office at the local, state, and federal levels and served in the highest tier of the nation’s government. It is this last achievement that I concentrate on—studying the women who have served at the most senior level of the president’s advisory system. Beginning in 1957 when Anne Wheaton became the first woman to serve in a non-clerical position as associate press secretary to President Dwight Eisenhower, women have made slow but steady progress in filling the top echelons of the president’s staff.

It goes without saying that the men and women who work closely with the president are among the most influential, unelected individuals in the U.S. government. They provide critical advice to the chief executive on myriad issues that, taken together, have a profound impact on the American way of life. According to presidential scholar Bradley Patterson, “Staff members have zero legal authority in their own right, yet 100 percent of presidential authority passes through their hands.”1 Though the president’s closest advisers are typically men, over the last three decades women have made important breakthroughs: OMB Director Alice Rivlin; National Security Advisor Condoleezza Rice; Senior Advisor to the President Valerie Jarrett; and CIA Director Gina Haspel to name a few. In an effort to illuminate the role of women on the president’s A Team, this article utilizes a new data set to explain, document, and analyze their contributions over the course of six presidential administrations, from 1981 to 2017.

Perhaps the most noteworthy development in the American presidency is the tremendous growth of the president’s advisory organization. The beginning of this expansion was marked by the release of the Brownlow Committee’s 1937 report recommending that “the President needs help.” This report led to the creation of the Executive Office of the President (EOP) and set off a gradual expansion of the staff over the next several administrations. Later, under President Nixon, there was an even larger expansion in the size of the White House staff, particularly in the realm of communications. Ever since, the trend has been one of increased expertise and policy centralization. In addition, new issues and unforeseen crises (e.g., 9/11 and the 2008 economic crash) have created new roles for the federal government and contributed to a continued expansion of the presidential staff.

At the same time, women have increased their role and status in the political realm—not just voting and increasing political participation, but more women hold elected office at the local, state, and national levels, and have served in senior positions throughout the federal government. Increased educational opportunities and access to employment options that were previously unavailable have allowed women to play pivotal roles in American politics. Careful analysis reveals, however, that such progress is not reflected at the top tier of the president’s staff. Just as women have only sporadically broken through the glass ceiling of major corporations, the same holds true within the group of senior presidential advisers.

Methodology

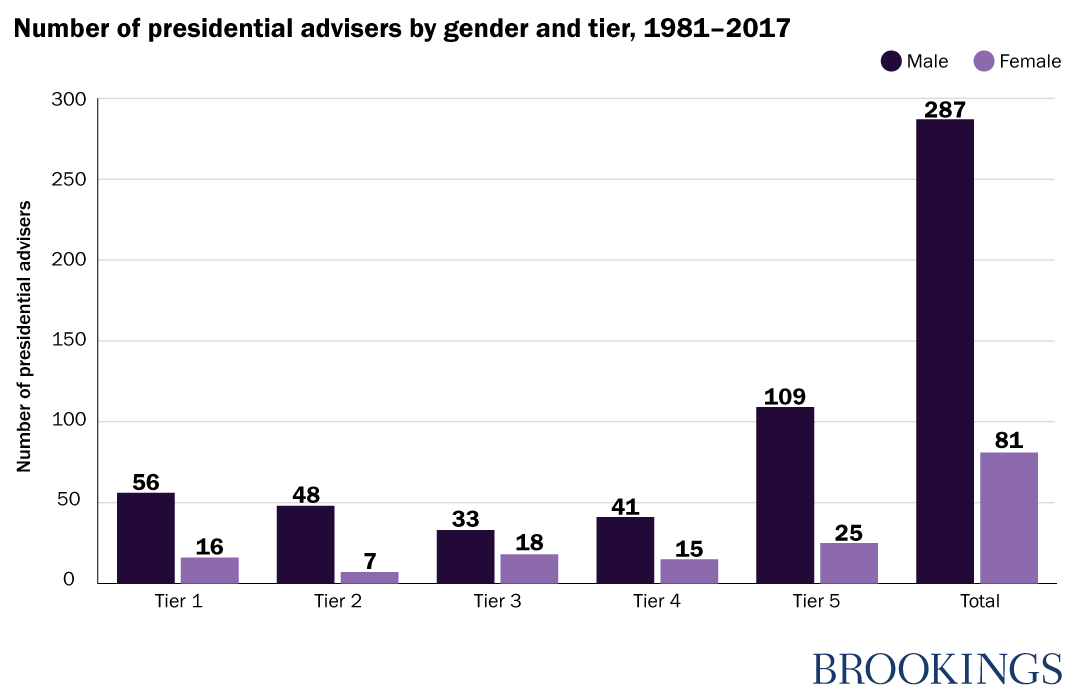

Obtaining a comprehensive, accurate list of the president’s staff is not possible, and identifying the president’s most influential staff is a complex and highly subjective task. There is little transparency in regard to the composition of a president’s staff, and government publications like The U.S. Government Manual are often incomplete or incorrect. Fortunately, the National Journal published a special volume called “Decision Makers” (what I call here the “A Team”) in which a team of reporters identified the most influential incoming staff members. Published for Presidents Reagan through Obama and released in spring or early summer of the first year in office, the National Journal’s special edition provides a staff listing and short biographies of those deemed to be “Decision Makers.” Across the five lists published, each profiled an average of 60 staff members from the Executive Office of the President. (Note that the National Journal reporters were not systematic about selecting every entity in the EOP; most staff members identified were from the White House Office and the remainder worked at other entities like the Office of Management and Budget, the National Security Council, or Office of the First Lady.) Since the National Journal was no longer publishing in 2017, I and journalist Madison Alder took an inventory of all “Decision Maker” positions and filled in Trump’s advisers in the fall of 2017. Taken together, there are 368 A Team members across all six administrations. Of those, 81 are women (22%). In an effort to shed light on this subset of female “Decision Makers,” I have gathered additional demographic data from a variety of online sources and analyzed the types of jobs these women have held.

Findings

In order to understand the lay of the land, it is important to provide a historical overview of female representation on the president’s A Team. The table below illustrates how the percentage of women has increased since the Reagan administration, but that women currently remain well under-represented—only exceeding 33% representation during the Obama administration.

Relative Seniority

As noted above, the five National Journal “Decision Maker” editions have provided a listing of the most influential positions in the president’s advisory organization. In an effort to rank the relative seniority of these jobs, I have divided the roles into five tiers. Tier One being the most influential down through Tier Five. Tier One includes those positions that were highlighted in every edition of the National Journal’s “Decision Makers,” thus signifying enduring importance across administrations and the most influential positions. Tier Two jobs were named in four of the five editions, Tier Three were listed in three out of five editions, Tier Four jobs were listed in two of the five editions, and Tier Five jobs were only listed once (in other words, the jobs were only identified as “Decision Makers” in a single administration).

Once again, women are underrepresented among the most influential, Tier One, roles. In fact, this bar chart demonstrates how men outnumber women in every single tier and, at times, by staggering margins.

Types of Positions

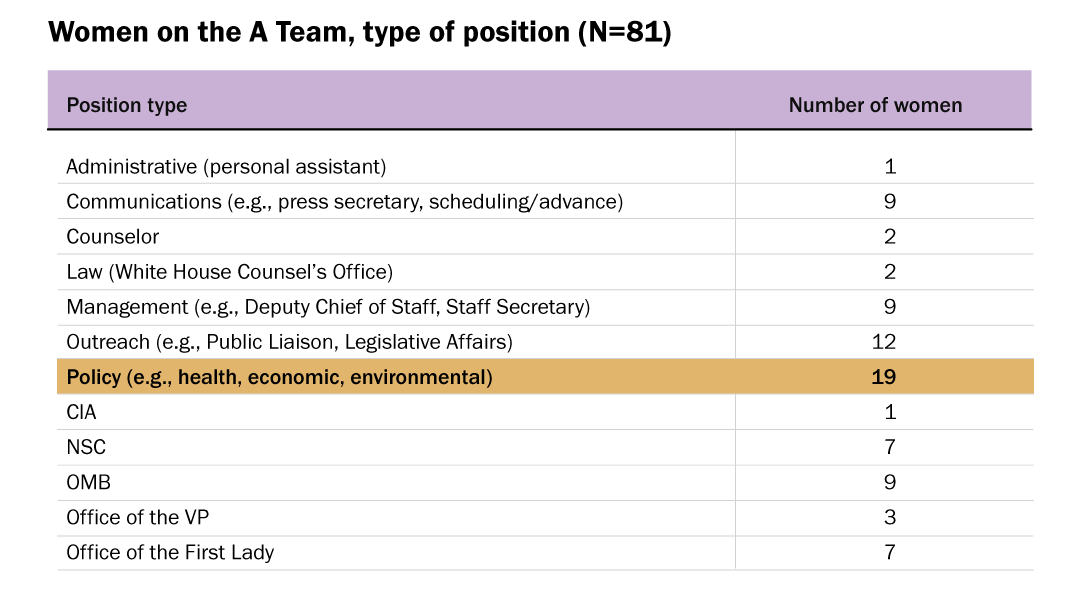

Moving beyond the numbers, it is worthwhile to consider the range of jobs held by these 81 women on the president’s A Team. I have created twelve categories of jobs: administrative, communications, counselor, law, management, outreach, policy, and the various subunits included in the National Journal’s “Decisionmakers” editions (CIA, NSC, OMB, Vice President’s staff, First Lady’s Staff).

The table above suggests that women are best represented in policy-related roles, followed (by a wide margin) by outreach types of positions. The number working in substantive policy jobs is encouraging: if the policy category was expanded to include OMB and NSC jobs, it would come close to representing almost half of the total positions occupied by women on the A Team. Unlike earlier eras in which women primarily filled clerical jobs on the president’s staff, this data provides a sense of the inroads that women have made in the policy realm.

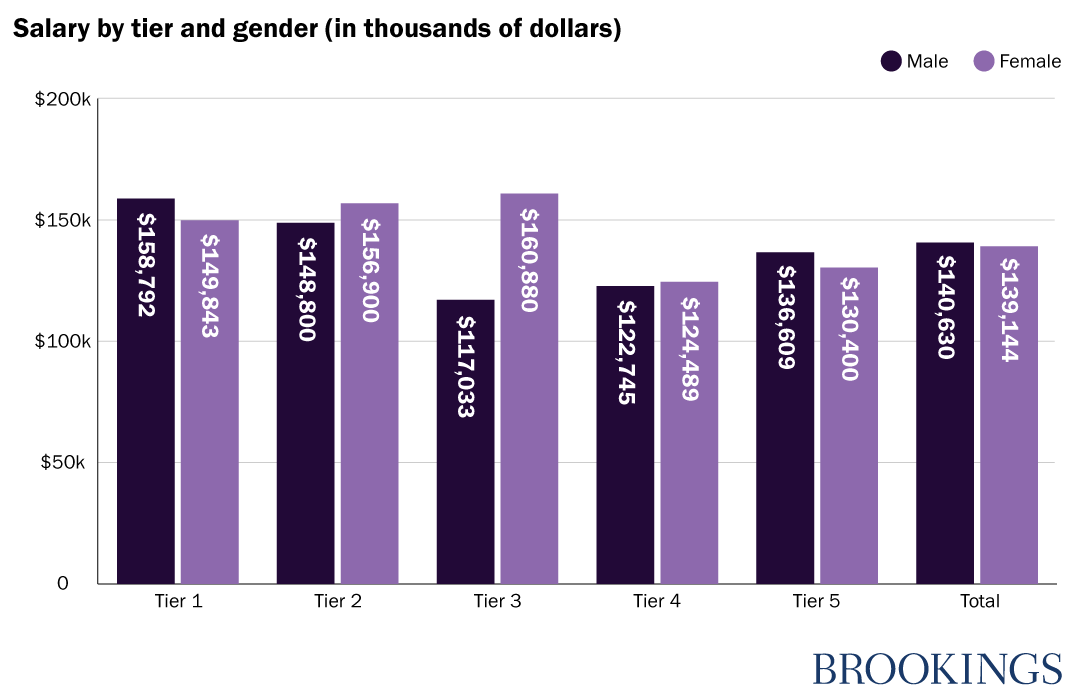

Salary

Another indicator of women’s progress is salary. Midway through the Clinton administration, presidents were required to send a report to Congress indicating the name, position, and salary of White House staffers. Meshing the salary data with A Team data allows me to compare White House salaries for Presidents George W. Bush, Barack Obama, and Donald Trump. Since the A Team data set includes non-White House positions like OMB and the vice president’s staff, I do not have salary data for the entire A Team. For the purposes of illustration, however, I have provided salary data for those men and women who worked in the White House and were part of the A Team.

Though the sample size is small (92 men and 36 women), this salary data reveals relatively minor differences between men and women except for Tier 3 jobs, wherein women commanded a significantly higher salary, approximately $44,000 more (on average) than their male counterparts in that tier. Upon closer inspection of the individual level data, this discrepancy may be the result of President Trump’s former National Economic Director, Gary Cohn, who requested the salary of $30,000. This outlier likely skewed Tier 3 salary data. The overall minor discrepancies might also be explained by the fact that presidentially commissioned, White House titles (assistant to the president, deputy assistant, and special assistant) are assigned specific salary ranges, such that one would not expect to see a great deal of variation within those subgroupings.

Career Path

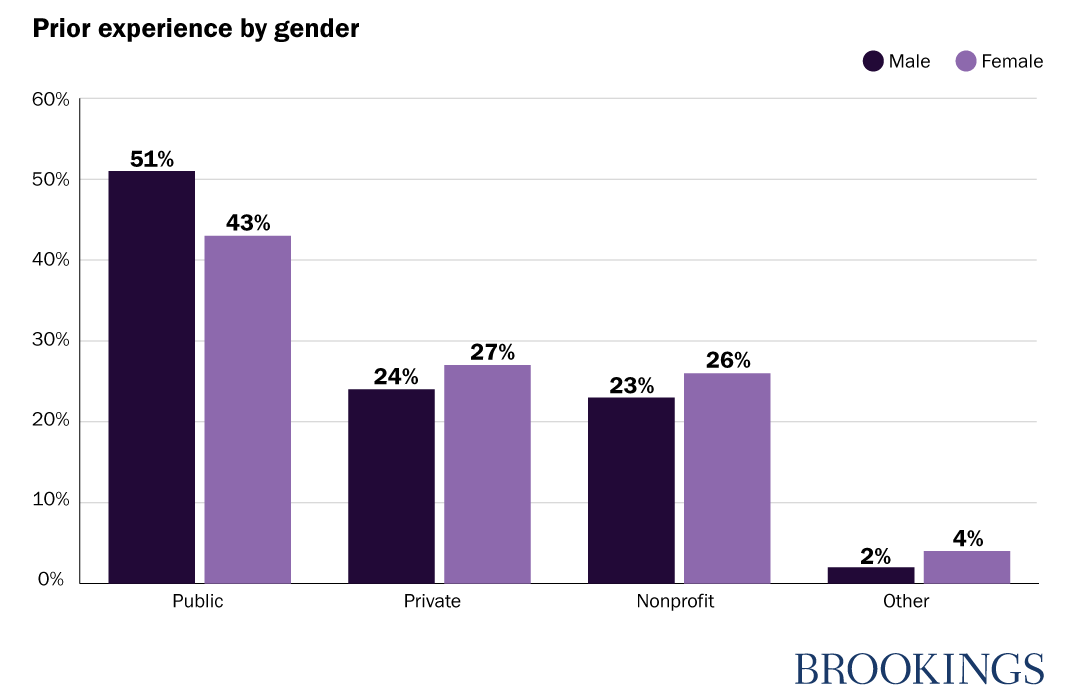

Similar to the private sector, obtaining a position at the highest level of the president’s staff necessitates that women have access to “stepping stone” jobs (e.g., working for a member of Congress, a political campaign, a state governor) that pave the way for securing more senior positions in the president’s advisory network. In an effort to illuminate career backgrounds before entering the White House, the table below compares men and women. I have taken specific jobs and categorized them broadly according to public, private, non-profit and other jobs (“other” includes roles like graduate student, parenting or self-employed).

Public sector jobs largely include government positions (local, state, national) and appear to be the dominant “feeder” into the White House. These jobs can include positions in state government, on Capitol Hill, or throughout the executive branch. It is worth noting that in all administrations (though much less so in the Trump administration) there has tended to be a practice of promotion over time, such that if you served in the Carter administration there was a strong chance that you would be recruited to work for the Clinton administration at a more senior level. The importance of prior White House experience (and the concomitant trait of possessing a network that could help obtain a more senior position) has been paramount when transition teams recruit. The data above indicates that women trail their male counterparts by eight percentage points in terms of public sector backgrounds. While not a huge margin, this trend may suggest that women need more access to this type of stepping stone job in order to gain access to more senior White House roles.

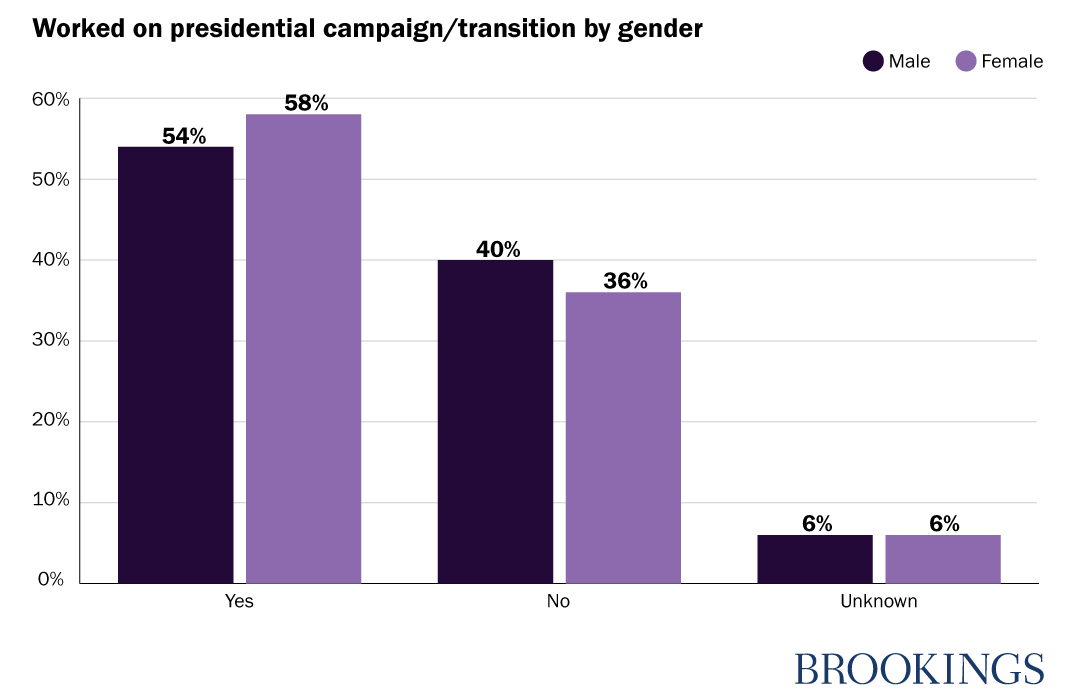

In addition, working on the winning candidate’s presidential campaign or transition is often thought to pave the way to an administration position. The data below indicates the percentage of women and men working on the president’s victorious campaign or transition.

This data suggests that the campaign or transition experience is an accessible, common stepping stone to women’s eventual role in the administration.

Concluding Thoughts

As we celebrate the centennial of the 19th Amendment, it is important to recognize and applaud women’s expanded presence at the most senior level of the president’s advisory organization. Consider a book published in 1968 titled, The President’s Men, by Patrick Anderson, in which he profiled 26 key staff members in five administrations (FDR to LBJ). The title alone is mind-boggling. The only two women whom he singled out were the personal assistants to Presidents Franklin Roosevelt and John Kennedy: Marguerite “Missy” LeHand and Evelyn Lincoln. Fifty plus years later, it is hard to fathom writing such a book. Nevertheless, the road ahead requires continued dedication, persistence, and support. Writing in 1997, specifically on the role of women on the White House staff, I concluded:

The outlook for women grows dimmer, however, when one considers their role at the most senior level of the White House staff. Shattering the glass ceiling will likely prove formidable, since it will require far more influence and power than any job title or advanced degree can confer.2

Sadly, the conclusion for this article (albeit analyzing different data and doing so nearly a quarter of a century later) is much the same. The percentage of female “Decision Makers” is astoundingly low, particularly in light of the broader gains that women have made in American politics over these many years. This conclusion echoes the findings of my colleague, Janet Yellin, who wrote “women continue to be underrepresented in certain industries and occupations”—clearly the president’s advisory organization is one such “industry.” While reluctant to celebrate the slow progress of women’s access to the most influential, unelected jobs in the U.S. government, I have no doubt that the ranks of qualified women will grow as well as the desire to break through to this highest tier of service.

Special thanks for expert research assistance from Caroline Malin-Mayor and Marla E. Odell.

- Bradley H. Patterson, The White House Staff: Inside the West Wing and Beyond (Brookings Institution Press, 2000), p, 2.

- Kathryn Dunn Tenpas, “Women on the White House Staff: A Longitudinal Analysis, 1939–1994,” in The Other Elites: Women, Politics, and Power in the Executive Branch, Maryanne Borrelli and Janet Martin, eds. (Lynne Rienner Publishers, 1997), p. 102.

This piece is part of 19A: The Brookings Gender Equality Series. Learn more about the series and read published work »