Editor’s Note: This analysis is part of the USC-Brookings Schaeffer Initiative for Health Policy, which is a partnership between Economic Studies at Brookings and the University of Southern California Schaeffer Center for Health Policy & Economics. The Initiative aims to inform the national health care debate with rigorous, evidence-based analysis leading to practical recommendations using the collaborative strengths of USC and Brookings.

Under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), insurers are required to offer reduced cost sharing to Marketplace enrollees with incomes below 250% of the federal poverty level (FPL) who enroll in silver plans. In the early years of the ACA, the federal government made payments to insurers to compensate them for the cost of providing these cost-sharing reductions (CSRs). Following a legal dispute over whether the ACA appropriated the funds needed to make CSR payments, the Trump administration ended these payments in 2017. Insurers responded by raising the premiums they charged for silver plans to offset the now-uncompensated cost of continuing to provide CSRs, a practice commonly called “silver loading.”

The transition to silver loading has turned out to be a boon for Marketplace consumers. Because the value of the ACA’s premium tax credit is linked to the premiums of silver plans, silver loading increased the value of the premium tax credit. Thus, for subsidy-eligible Marketplace consumers (the large majority of Marketplace enrollees), silver loading has reduced the net premiums of non-silver plans, while leaving the net premiums of silver plans unchanged. Evidence indicates that this change has increased Marketplace enrollment. The combination of larger premium tax credits and higher enrollment has also increased federal costs, even after netting out what the federal government saved on CSR payments.

In essence, silver loading has brought about an expansion of the ACA’s Marketplace subsidies, with the main costs and benefits that entails. But viewed as a way of expanding subsidies, silver loading does have some unappealing features. Most importantly, a future administration that was hostile to the ACA might seek to end silver loading administratively, which would unwind silver loading’s benefits for Marketplace consumers and could create other problems. Additionally, the fact that silver plans are now “overpriced” for enrollees ineligible for generous CSRs has driven some of those enrollees into non-silver (mostly bronze) plans with levels of cost-sharing that are a worse match for their needs. Silver loading also creates disincentives for states to expand Medicaid or adopt a Basic Health Program.

If Congress wanted to preserve silver loading’s benefits for Marketplace consumers while avoiding these issues, it could enact an appropriation for CSR payments and use the savings to directly expand the ACA’s Marketplace subsidies. Policymakers have many options for how they could reinvest the savings, and the choice among them would depend on their objectives. However, if policymakers wished to mirror the benefits generated by silver loading in order to minimize disruption, one option would be to modify the benchmark premium used to calculate the premium tax credit. For example, policymakers could make the benchmark premium some multiple of the second-lowest silver premium (rather than just the second-lowest silver premium) or make the benchmark plan a gold (rather than silver) plan.

A potential obstacle to reinvesting the savings from ending silver loading is that the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) has previously said that it would not score the savings from providing an appropriation that would allow a resumption of direct CSR payments, even though it agrees that resuming CSR payments would save the federal government money. However, CBO has said that this scoring approach was arrived at in consultation with the House and Senate Budget Committees, so it is likely that the Budget Committees could work with CBO to arrive at a revised scoring treatment that does count these savings.

The remainder of this analysis discusses these points in greater detail.

Background on “Silver Loading”

Under the ACA, Marketplace insurers are required to offer reduced cost-sharing to people enrolled in silver plans who have incomes between 100% and 250% of the FPL.[1] CSRs increase the actuarial value of a silver plan from its base value of 70% to 94% for people with incomes in the 100-150% of FPL range, 87% for people with incomes in the 150-200% of FPL range, and 73% for people with incomes in the 200-250% of FPL range. (Below, I use the shorthand “generous CSRs” to refer to the CSRs available to people with incomes below 200% of the FPL.) CSRs are generally not available on non-silver plans.

The ACA required the federal government to make periodic payments to insurers to compensate them for the cost of providing CSRs, which is how the CSR program operated until late 2017. But there was a legal dispute in the ACA’s early years about whether the ACA had actually appropriated funds the federal government could draw on to make these payments. In October 2017, the Trump administration adopted the position that the ACA had not appropriated the needed funds and ended the payments.

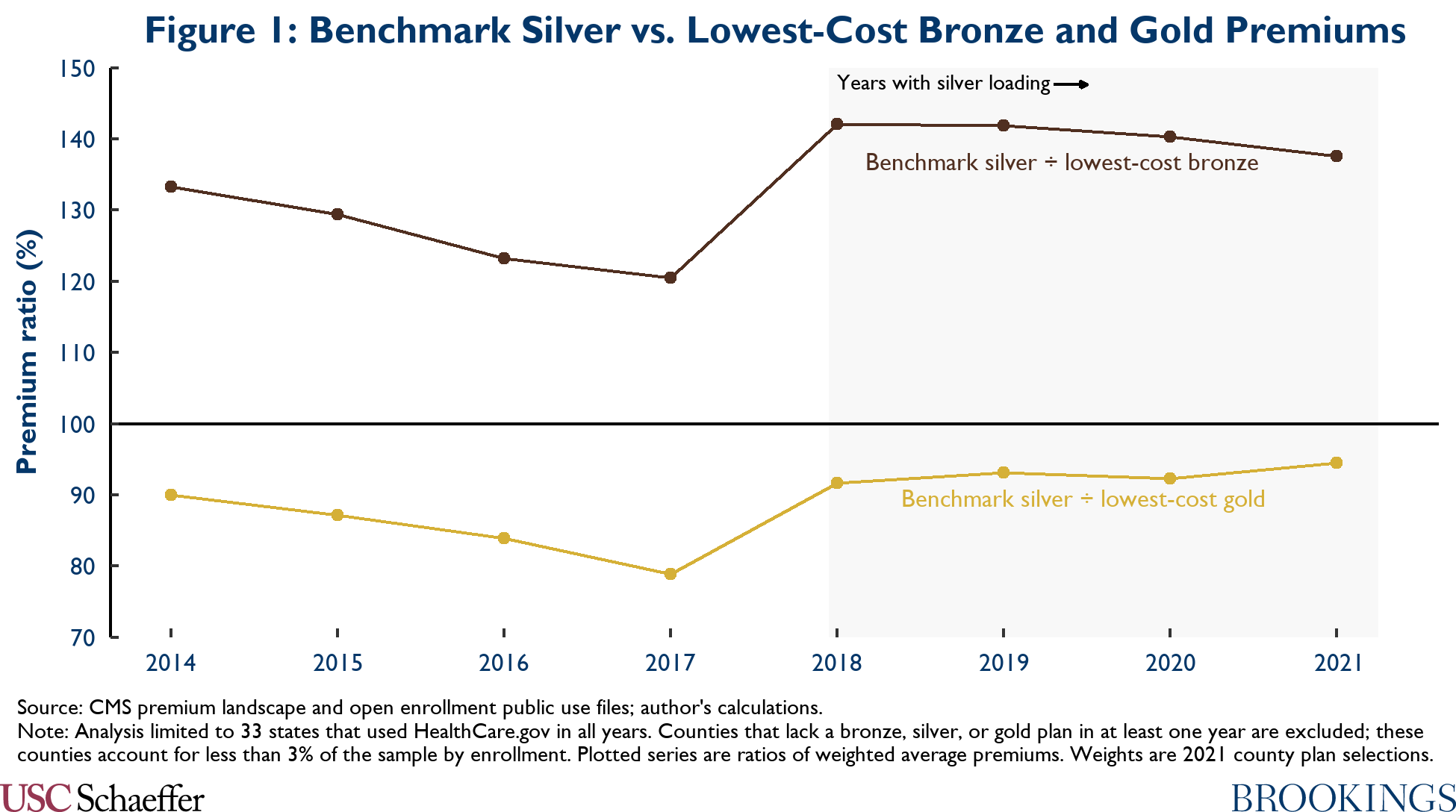

While President Trump appears to have viewed this action as a way of undermining the ACA, the actual results were quite different.[2] The end of CSR payments increased the cost to insurers of selling policies in the silver tier since insurers still had to offer CSRs to eligible enrollees but were no longer compensated for it. Correspondingly, insurers generally responded by raising the premiums they charged for silver plans (but not other plans) a practice commonly known as “silver loading.”[3] Figure 1 shows that the premiums of silver plans rose sharply relative to the premiums of gold and bronze plans in 2018.

Crucially, however, the value of the ACA’s premium tax credit is based on the premiums of silver plans (specifically, the second-lowest cost silver plan, often called the “benchmark” plan), so when premiums of silver plans rise, the value of the tax credit rises dollar-for-dollar. Thus, the advent of silver loading had basically no effect on the premiums that subsidy-eligible enrollees pay for silver plans, and it reduced the premiums that subsidy-eligible enrollees pay for plans in other metal tiers. Notably, silver loading substantially increased the number of enrollees eligible for zero-premium bronze plans.

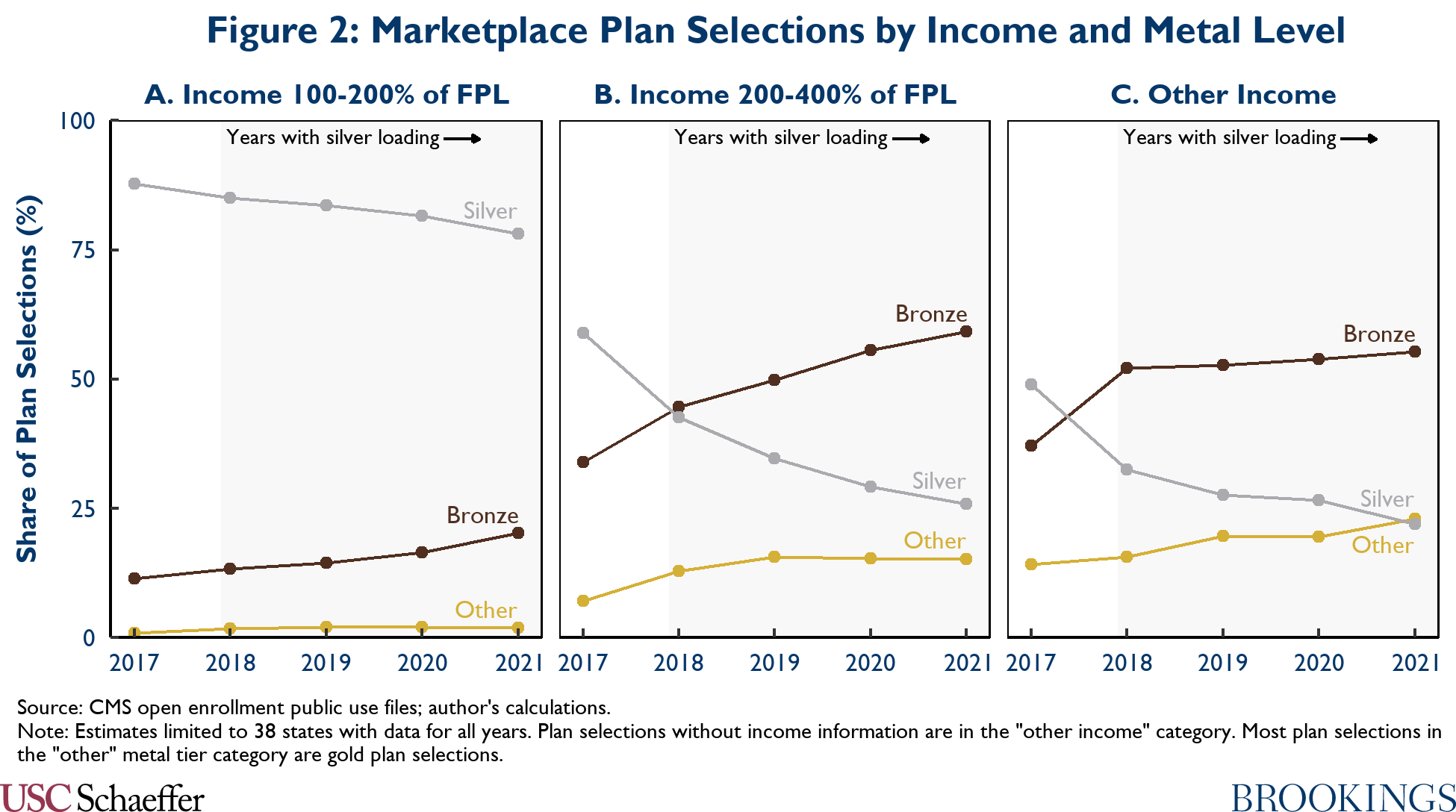

These changes have not affected all enrollees equally. Enrollees with incomes in the 100-200% of FPL range are mostly unaffected because they are eligible for generous CSRs and so overwhelmingly enroll in silver plans even under silver loading (see Figure 2, Panel A). By contrast, subsidized enrollees with incomes above 200% of the FPL have benefited substantially. These enrollees are eligible for small or no CSRs, so they selected non-silver plans in large numbers even before silver loading, and many more have switched into non-silver plans to take advantage of the decline in net premiums for those plans (see Figure 2, Panel B). Unsubsidized enrollees who previously selected silver plans are potentially worse off, but in most states insurers have limited silver loading to on-Marketplace silver plans, so enrollees can avoid the silver load by switching to off-Marketplace plans if they wish. Regardless, there will be fewer unsubsidized enrollees going forward if the extension of the premium tax credit to people with incomes above 400% of the FPL in the American Rescue Plan Act is made permanent in the coming months.

Evidence suggests that silver loading has increased Marketplace enrollment. People with incomes in the 200-400% of FPL range, the main group that benefited from silver loading, saw higher Marketplace enrollment growth following the transition to silver loading relative to enrollees at lower income levels. More compelling, states that saw larger increases in silver premiums following implementation of silver loading saw faster enrollment growth—and that additional enrollment growth was concentrated in the 200-400% of FPL group that benefited most from silver loading. These findings are consistent with projections from microsimulation models that predicted silver loading would increase Marketplace enrollment (and empirical work in other settings showing that reducing premiums increases enrollment).

By increasing the value of the premium tax credit and increasing Marketplace enrollment, silver loading has also increased federal costs—even after netting out the federal savings from no longer making CSR payments. In brief, the increase in premium tax credits paid out on behalf of silver plan enrollees have approximately offset the savings from the lack of CSR payments,[4] while the increased premium tax credits paid on behalf of non-silver enrollees and the tax credits provided to new enrollees have represented new federal costs. Consistent with this, CBO previously projected that resuming direct CSR payments would reduce federal costs by around $10 billion per year over the 2019-2021 period.[5]

Absent policy changes, it appears likely that silver loading will continue indefinitely. While insurers sued the federal government to recover the missing CSR payments, court rulings issued in August 2020 held that insurers are entitled to compensation only to the extent that they have failed to mitigate their losses by raising silver premiums and receiving higher premium tax credits; this implies that most insurers will recover little or nothing for years after 2017. Moreover, the logic of these court decisions suggests that insurers that have the opportunity to silver load but decline to do so might be entitled to nothing. Thus, it appears that insurers will struggle to recover CSR payments through litigation, implying that their best response to the continued lack of CSR payments will be to continue silver loading in the years to come.

Rationales for Replacing Silver Loading

The transition to silver loading has, in effect, brought about an expansion of the ACA’s Marketplace subsidies, with the main benefits (lower premiums for enrollees and broader insurance coverage) and costs (higher federal costs) that such expansions typically entail. Correspondingly, policymakers who generally oppose Marketplace subsidy expansions have good reason to support resuming CSR payments and thereby returning to the pre-silver-loading status quo. By contrast, policymakers who generally support Marketplace subsidy expansions are likely to look favorably on silver loading. Nevertheless, for several reasons, policymakers in the latter group may wish to consider replacing silver loading by resuming CSR payments and using the savings to finance a direct expansion of Marketplace subsidies.

A future administration could attempt to end silver loading administratively

One important rationale for replacing silver loading is that a future administration could try to end silver loading administratively. In particular, a future administration could seek to force insurers to spread the cost of the missing CSR payments across premiums in all metal tiers instead of just the silver tier, an approach sometimes called “broad loading.” By reducing silver premiums, this approach would reduce federal premium tax credit costs, but it would increase premiums for people buying non-silver plans since these enrollees would now pay higher gross premiums and receive smaller tax credits. Thus, this approach would unwind the main benefits that silver loading provides to Marketplace enrollees.

Broad loading would also create some pernicious incentives. Under broad loading, insurers would incur large losses on their silver plans since premiums for those policies would no longer reflect the full cost of providing CSRs. On the other hand, they would now make large profits on their non-silver plans since premiums for those plans would be set to defray CSR costs that those plans did not incur. In this environment, insurers would have strong incentives to make their silver plan offerings unappealing to consumers in order to push enrollees out of silver plans and into non-silver plans.[6] This behavior would particularly harm people who are eligible for CSRs since CSRs are only available in silver plans.

It is not hard to imagine a future administration that was hostile to the ACA (or that simply viewed the reduction in federal spending from ending silver loading as more important than the corresponding reduction in insurance coverage and increase in enrollees’ premiums) might go down this path. Indeed, the Trump administration appears to have seriously considered taking action to end silver loading. Congress took this threat seriously enough that it barred the administration from taking any action to end silver loading for the 2021 plan year in appropriations legislation enacted in December 2019.

Now, a future administration might not be successful in moving to broad loading even if it tried. One issue is that enforcing broad loading would be challenging in practice. Under-pricing silver plans and over-pricing non-silver plans is not in any insurer’s interest, so insurers would likely try to “cheat” away from broad loading and toward silver loading to the extent they could get away with it. In practice, they would likely be at least somewhat successful since regulators likely could not perfectly distinguish surreptitious silver loading from permissible premium differences between silver and non-silver plans.

Mandating broad loading might also be illegal. While the ACA regulates how insurers can vary the premiums they charge different enrollees for the same plan, it generally does not regulate how the premiums of different plans must relate to each other, beyond a general requirement that insurers cannot set the premiums of different plans to reflect differences in risk mix.[7] Insurers might therefore reasonably argue that mandating broad loading would go beyond the federal government’s authority.

Silver loading has driven some enrollees into coverage that poorly matches their needs

Even if silver loading were guaranteed to continue, there would still be other rationales for replacing it. Most importantly, for enrollees who are not eligible for generous CSRs, silver loading causes silver plans to be “overpriced” relative to other plans. This has caused a large shift out of silver plans among people with incomes above 200% of the FPL, most of it into bronze plans (see Figure 2, Panels B and C).

Because of these shifts, many subsidized enrollees with incomes above 200% of the FPL are likely now in the “wrong” level of coverage. To be precise, many enrollees who have shifted into bronze plans would likely prefer a silver plan if the silver plan’s premium reflected the actual cost-sharing they would pay, rather than primarily reflecting the cost-sharing faced by enrollees who are eligible for generous CSRs. Thus, unless these enrollees were mistakenly opting for plans with too little cost sharing prior to the implementation of silver loading, something there is not much evidence for, these enrollees are likely now in plans that include too much cost sharing.[8] (Similarly, many of the much smaller number of enrollees who have shifted into gold plans may now be in plans with too little cost-sharing.)

To be clear, this does not mean that silver loading has made subsidized enrollees in this income range worse off. Enrollees who previously bought silver plans had the option to stay in silver plans without paying a higher premium (since the premium tax credit offset the increase in silver premiums). The fact that they nevertheless shifted into non-silver plans indicates that they viewed these plans as better options than they had before. However, these enrollees would have been even better off if they could have benefited from the increase in the value of the premium tax credit caused by silver loading while staying in silver plans, which a replacement for silver loading could make possible.

Shifts out of the silver tier are less consequential for unsubsidized enrollees. As noted above, unsubsidized enrollees generally have the option of switching to off-Marketplace silver plans that do not incorporate a CSR load. To the extent this has occurred in practice, the cost that these enrollees incur from leaving Marketplace silver plans are mostly limited to hassle costs. Additionally, unsubsidized enrollees will become rarer if the subsidy expansions in the American Rescue Plan Act are made permanent.

There has also been a modest shift out of silver plans among enrollees with incomes below 200% of the FPL (see Figure 2, Panel A). Many of these enrollees are likely making mistakes in light of the very large differences in cost-sharing between bronze and silver plans for these enrollees (although, by making the value of CSRs partially “portable” across metal tiers for people in this income group, silver loading may also have allowed some enrollees to opt for plans with a mix of premiums and cost-sharing that better meets their needs). Regardless, if the subsidy expansions in the American Rescue Plan Act become permanent, most of these enrollees are likely to shift back into silver plans whether or not silver loading continues since these expansions guarantee a zero premium silver plan to everyone with an income below 150% of the FPL and a very low or zero premium silver option to everyone below 200% of the FPL.

Silver loading creates disincentives to expand Medicaid or adopt a Basic Health Program

A final rationale for replacing silver loading is that doing so could eliminate a modest disincentive for states to expand Medicaid. When a state expands, people with incomes between 100% and 138% of the FPL lose eligibility for Marketplace coverage and instead become eligible for Medicaid, thereby removing most people with 94% actuarial value CSRs from the Marketplace. This in turn reduces insurers’ need to silver load; the average actuarial value of Marketplace silver plans (inclusive of the value of CSRs) is 90% in non-expansion states versus 84% in expansion states.[9] The resulting reduction in silver premiums diminishes the benefits of silver loading for the higher-income enrollees who remain in the Marketplace, so Medicaid expansion has the unintended effect of making these enrollees somewhat worse off.

Even taking account of this interaction with silver loading, expanding Medicaid is an overwhelmingly attractive proposition for states in light of the benefits of Medicaid expansion for access to care, health, and financial security, as well as the fact that the federal government picks up 90% of the long-run cost. Nevertheless, eliminating this modest disincentive for expansion would likely be worthwhile.

Silver loading creates a much larger disincentive for states to adopt a Basic Health Program (BHP). As background, under the ACA, states have the option to create a BHP as a substitute for Marketplace coverage for people with incomes under 200% of the FPL. States that opt for a BHP receive per enrollee payments from the federal government equal to 95% of what the federal government would have paid on behalf of those enrollees in the Marketplace. New York and Minnesota currently operate BHPs, and their programs offer lower premiums and cost-sharing than Marketplace coverage. (This is likely because the existing BHPs offer Medicaid-like plans that pay providers less than Marketplace plans, and the states are then using the savings to offer more generous benefits to BHP enrollees.)

Creating a BHP shifts all enrollees who are eligible for generous CSRs out of the Marketplace and into BHP. This all but eliminates the need for insurers to silver load, which in turn essentially eliminates the benefits of silver loading for the higher-income enrollees who remain in the Marketplace.[10] In light of this fact, it is doubtful that it currently makes sense for states that do not already have a BHP to adopt one. To the extent that broader adoption of BHPs is desirable, this is a downside of silver loading.

Options to Replace Silver Loading

If policymakers do want to resume direct CSR payments and reinvest the savings by directly expanding the ACA’s Marketplace subsidies, they have two main decisions to make about how to do so.

Decision #1: Expanding premium tax credits vs. expanding CSRs

A first decision is whether to reinvest funds by expanding the premium tax credit or by expanding CSRs. Expanding the premium tax credit would lower premiums in all metal tiers and then allow consumers to select whether they prefer plans that offer higher premiums and less cost-sharing or prefer plans that offer lower premiums and more cost-sharing. This approach is more attractive to the extent that consumers vary in what mix of premiums and cost-sharing best suit their needs and do a good job of choosing plans in accordance with those varying needs. Additionally, this approach would also tend to increase the number of consumers who have a zero-premium plan option available to them, which may have a particularly large effect on enrollment outcomes, plausibly by eliminating the hassle costs associated with remitting a monthly premium. Broader availability of zero-premium plan options could also facilitate various types of automatic enrollment efforts.

By contrast, CSRs are only available to people enrolled in silver plans, so expanding CSRs would make silver plans more attractive without changing the attractiveness of other plans.[11] This may be desirable if policymakers are concerned that consumers do a poor job weighing tradeoffs between lower premiums and higher cost-sharing (which there is evidence for in at least some contexts) and thus wish to steer consumers toward plans with a particular mix of premiums and cost-sharing. A risk of this approach is that some enrollees might not respond to the incentives policymakers were aiming to create and, thus, would end up enrolling in non-silver plans that do not provide the additional assistance; this is the case today for a small, but not trivial, minority of people with incomes below 200% of the FPL (see Figure 2, Panel A).

Decision #2: How to target the reinvested funds

Policymakers would also need to decide what types of enrollees to target with the reinvested funds. From a substantive perspective, that choice should likely be shaped by two factors. The first is where additional assistance would do the most to increase insurance coverage. Those effects could vary by income (although it is not immediately clear how since take-up of ACA-compliant coverage was incomplete at all income levels as of 2019) or by other characteristics like age; they would also likely depend on whether the broad-based expansion of the premium tax credit enacted in the American Rescue Plan Act (ARP) had been made permanent. The second is where additional assistance would do the most to relieve financial hardship; in general, this consideration argues for targeting additional assistance at people with lower incomes, where household budgets are likely to be tightest.

In practice, policymakers might see political advantages to reinvesting funds in a way that mirrored the benefits of silver loading in order to minimize the number of consumers made worse off by replacing silver loading. These political advantages might be smaller if legislation that replaced silver loading also made the ARP subsidy expansions permanent since very few consumers are likely to be made worse off by the combined package. However, that might only be true if consumers first encountered the end of silver loading at the same time they first encountered the ARP subsidy expansions. That likely will not be the case in practice. Premium setting is already underway for the 2022 plan year, so an end to silver loading will likely need to wait until the 2023 plan year, whereas some Marketplace consumers are already receiving the enhanced ARP subsidies and the rest will during open enrollment for 2022.

Policy approaches that would closely mirror the benefits of silver loading

If policymakers decide that their priority in reinvesting the savings from ending silver loading is to replicate the consumer benefits created by silver loading as closely as possible, then there is a straightforward way to do so. Specifically, policymakers could change the benchmark premium that is used to calculate the premium tax credit to be a multiple of the second-lowest-cost silver premium (rather than the second-lowest-cost silver premium itself, as is the case today) for enrollees not enrolled in generous CSRs.

If this multiple was selected so that the benchmark premium under the policy (for the enrollees eligible for the new higher benchmark) equaled the benchmark premium that would have prevailed if silver loading had continued, then this change to the premium tax credit would almost exactly reproduce the pattern of consumer benefits created by silver loading. The exception is that this approach would reduce the net premiums of plans in all metal tiers, not just the premiums of non-silver plans.

As described in the appendix, I estimate that, on average nationwide, the second-lowest-cost silver premium is currently around 28% higher than it would have been if direct CSR payments had continued. Thus, setting the benchmark premium at 128% of the second-lowest cost silver premium would approximately replicate the benefits of silver loading. It is important to note that while this would be true on average, it would be not be true in every geographic area since the impact of silver loading varies across areas due to differences in the income mix of CSR enrollees and other market-specific factors. The percentage increase in the benchmark required to replicate the effects of silver loading could also change over time if the impact of silver loading changed over time; this could occur if people ineligible for generous CSRs continue to migrate out of silver plans, as suggested by the trends shown in Figure 2.

The cost of enhancing the premium tax credit in this way would likely modestly exceed the savings from ending silver loading because this type of subsidy expansion would benefit silver enrollees, whereas silver loading does not. In the appendix, I estimate an incremental cost of around $2.3 billion per year over the 2023-2030 period relative to current law (or $3.0 billion per year over that period if the ARP subsidy expansions were made permanent). As discussed in the appendix, this estimate is relatively crude and accounting for factors omitted from this simple estimate could reduce the estimated cost modestly.

A related—and more elegant—approach to reinvesting the savings from ending silver loading would be to change the benchmark plan to be the second-lowest-cost gold plan rather than the second-lowest cost silver plan (and, correspondingly, to modify CSRs so that they are available on gold plans rather than silver plans). This type of policy has been previously proposed by researchers at the Urban Institute.

At first blush, this “re-benchmark to gold” policy appears to be much more expensive than the policy outlined above since, on average nationwide, the second-lowest cost gold premium is about 12% higher than the second-lowest cost silver premium.[12] But for two reasons, that may not be the case.[13]

First, re-benchmarking to gold would likely reduce the average claims risk of gold enrollees. At present, it appears that gold plans are attracting much sicker enrollees than silver plans (in ways that risk adjustment is not offsetting); indeed, without a substantial difference in risk mix, it is hard to explain why gold premiums are higher than silver premiums even as the average actuarial value of a Marketplace silver plan (87% on average nationwide, inclusive of CSRs) exceeds the actuarial value of a gold plan (80%). However, if CSRs shifted from the silver tier to the gold tier, most people with generous CSRs would shift into gold plans. About 5.1 million people selected silver plans with generous CSRs during 2021 open enrollment (accounting for 77% of all silver plan selections), whereas only 1.0 million selected gold plans. Thus, shifting this group into gold plans would likely cause the risk mix in the gold tier to converge toward the current risk mix in silver, likely substantially reducing gold premiums. Second, the presence of more low-income consumers in the gold tier could intensify price competition, further reducing gold premiums.

Quantifying these effects would require further analysis, but it appears very likely that re-benchmarking to gold would be much less expensive that it looks—conceivably actually cheaper than continuing silver loading.[14] Reducing the premiums of gold plans could also directly benefit consumers who value plans with lower cost-sharing.[15] Thus, if policymakers do want to reinvest the benefits from ending silver loading in a way that would mirror the benefits of silver loading, this approach merits consideration.

I note that a disadvantage of either of these two approaches is that they (like silver loading) deliver roughly the same benefit to subsidized enrollees at all income levels, whereas targeting more of the assistance at lower income levels would likely do more to relieve financial hardship. If policymakers wanted to target more assistance to people with lower incomes, they could consider phasing out the more generous benchmark premium for consumers with incomes above a specified level.

Potential Scoring Obstacles

If policymakers concluded that they did want to provide an appropriation for direct CSR payments and then reinvest the savings that generated, they may face a scoring obstacle. Specifically, CBO has previously said that it would score a provision that appropriated CSR payments as having no effect on federal deficits, even though CBO agrees the provision would, in fact, reduce deficits. Thus, legislation that resumed direct CSR payments and reinvested the savings would be scored as increasing deficits.

Why has CBO adopted this odd scoring treatment? Under the law that governs how CBO constructs its baseline, CBO must assume that funding will be “adequate to make all payments required” under an entitlement program (that is, a program that, like the CSR program, gives some entity a legal right to a payment from the federal government).[16] Relative to that baseline, a provision that appropriates funds to make payments under an entitlement program typically has no budgetary effect, so CBO conventionally scores such a provision as causing no change in deficits. CBO has said in the past that it intends to apply that convention in scoring a provision that would appropriate CSR payments.

This scoring treatment would pose a problem if policymakers wanted to resume direct CSR payments and reinvest the savings. Legislation along these lines would likely need to be considered through reconciliation to avoid a filibuster in the Senate. But the Byrd rule, which governs Senate consideration of reconciliation bills, bars legislation that increases deficits outside the budget window.

However, this problem has a straightforward solution. In particular, CBO has said that its current scoring approach was arrived at in consultation with the House and Senate Budget Committees. Thus, the Committees could likely request that CBO adopt a scoring approach that accurately captures the real-world consequences of providing an appropriation to make direct CSR payments.

In addition to being more realistic, this alternative scoring approach would be simpler and more internally consistent. Indeed, CBO has sensibly decided that its baseline projections should reflect what is happening in reality: silver loading, not direct CSR payments.[17] CBO scores virtually all legislation against that realistic baseline. The sole exception is legislation that would resume direct CSR payments, which is, in effect, scored against a different baseline in which direct CSR payments are already occurring.

Appendix: Additional Methodological Details

Estimating the increase in benchmark premiums in 2021 due to the lack of CSR payments

The main text reports an estimate of the percentage increase in the average benchmark premium in 2021 due to the lack of CSR payments. This portion of the appendix describes how that estimate was derived.

In a simple competitive model, the change in the benchmark premium caused by the lack of CSR payments will equal the induced change in insurers’ average costs.[18] The lack of CSR payments may change insurers’ costs in at least three ways. First, and most importantly, insurers now bear the claims spending previously covered by CSR payments. Second, silver loading may cause people ineligible for generous CSRs to leave silver plans, as suggested by the trends in Figure 2, decreasing the amount of cost-sharing faced by the typical silver enrollee and thereby increasing utilization. Third, those same enrollment shifts may change the risk mix of silver enrollees, which could also change utilization in silver plans.

To arrive at my main estimate of how much silver loading has increased the benchmark premium, I perform a calculation that accounts for the first two channels. To that end, I use the 2021 open enrollment public use file published by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to estimate the average actuarial value of a Marketplace silver plan (inclusive of the value provided by CSRs). For states that use HealthCare.gov, I calculate the average actuarial value directly using data on how many people selected each tier of CSR. The public use file lacks the needed information for states that do not use HealthCare.gov, so I assume that the average actuarial value in other states is the same as the average for HealthCare.gov states with the same Medicaid expansion status.[19] Weighting each state by its total number of Marketplace plan selections, I obtain a national enrollment-weighted actuarial value of 86.7%. Using a similar method, I estimate that this actuarial value was 84.4% as of 2017.[20]

Under the assumption that 10% of insurers’ expenses do not scale with claims spending, the increase in the benchmark premium required to offset the direct loss of CSR payments is 21.4% (=0.9*[0.867/0.7] + 0.1). To estimate the contribution from higher utilization, I assume that the change in the average actuarial value of a silver plan since 2017 was entirely attributable to the transition to silver loading, and I treat a silver plan as if it had a constant coinsurance rate equal to one minus its actuarial value (an admittedly imperfect approximation). Applying a conventional elasticity of utilization with respect to price of -0.2 yields a utilization increase of 3.1% (=Exp[-0.2*ln[0.133/0.155]]). Combining these two effects yields an increase in the benchmark premium of 25.0% (=0.9*[0.867/0.7]*1.031 + 0.1).

All of the calculations presented above assume that the actuarial value of a silver plan without CSRs exactly equals 70% and that the actuarial value of a silver plan with CSRs exactly equals the nominal actuarial value of the relevant CSR tier (that is, 73%, 87%, or 94%). In practice, however, silver plans are permitted to have a base actuarial value as low as 66% and silver CSR variants are permitted to have an actuarial value up to 1 percentage point below the nominal actuarial value associated with that CSR tier.[21]

To account for this, I use CMS’ plan attributes public use file to obtain the actual actuarial value of the benchmark plan in each county that used HealthCare.gov in 2021. Using these data, I estimate that the base actuarial value of the benchmark plan averaged 68.3% in 2021, while the actuarial values of the corresponding 73%, 87%, and 94% actuarial value CSR variants averaged 72.9%, 87.3%, and 93.8%, respectively, where averages are weighted by county-level Marketplace plan selections. If these actuarial values are substituted for the nominal actuarial values in the calculations above, then my estimate of the average actuarial value of a Marketplace silver plan in 2021 becomes 86.4% and the corresponding estimate for 2017 is 84.1%. The estimated impacts on the benchmark premium also end up being slightly larger, primarily because of the lower base actuarial value of the benchmark plan; the estimated effect is 23.9% when ignoring utilization effects and 27.6% when incorporating those effects.

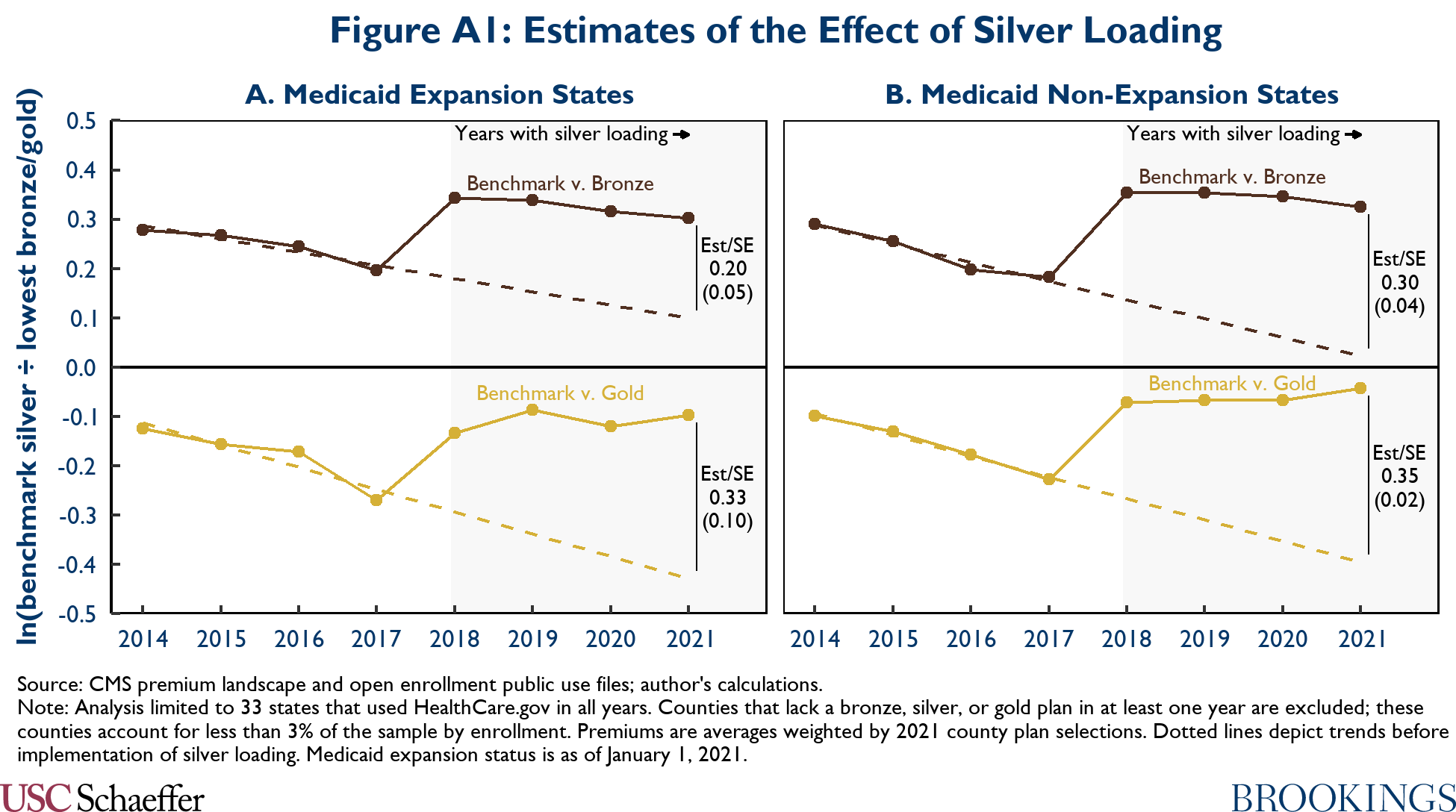

As a check on this model-based calculation, I also estimate how silver loading affected benchmark premiums by comparing the trend in benchmark premiums to the trends in lowest-cost gold and bronze premiums. The virtue of this approach is that it does not depend on a specific model of insurers’ pricing decisions. However, this approach does require that the trends in bronze and gold premiums be a reliable guide to the path that silver premiums would have taken without silver loading.

This assumption will fail if silver loading directly affects bronze and gold premiums, such as by changing the risk mix of people who select those plans. This assumption will also fail if other factors cause bronze and gold premiums to trend differently from silver premiums. Figure A1 shows that benchmark premiums were declining relative to both lowest-cost gold and bronze premiums prior to the start of silver loading (perhaps reflecting ongoing changes in risk mix across metal tiers); this suggests that this second issue is indeed a concern in this context. To cope with this problem, I assume that benchmark premiums would have continued their pre-silver-loading decline relative to lowest-cost bronze and gold premiums in the absence of the transition to silver loading; the implied paths are depicted by the dashed lines in Figure A1. While this assumption has intuitive appeal, its validity is subject to uncertainty, particularly absent a full understanding of why benchmark premiums were declining in relative terms prior to silver loading.

Figure A1 reports the resulting estimates of the causal effect of silver loading on benchmark premiums, disaggregated by Medicaid expansion status. To obtain summary measures from these estimates, I first convert the log point changes reported in Figure A1 to percentage point changes. I then compute an average of the resulting expansion and non-expansion estimates, weighting each estimate by the share of overall Marketplace plan selections accounted for by those states in 2021.[22] The estimated average effect of silver loading on benchmark premiums is 28% when comparing to bronze premiums and 40% when comparing to gold premiums. While these point estimates are subject to considerable uncertainty due to the uncertainty about the premium trends that would have been observed without silver loading, they do at least suggest the model-based estimates presented above are not substantially too large.

As a final check on the model-based calculations, I also examined whether states where silver loading had more “bite” (because a large share of silver plan enrollment was accounted for by people with generous CSRs) experienced larger increases in silver premiums. This approach also avoids adopting a particular model of how the lack of CSR payments affects premiums and, in theory, remains valid even if silver loading changes the premiums of non-silver plans. The results that emerge from this approach are broadly consistent with those from other methods. However, the estimates are relatively imprecise and sensitive to specification changes, so they do not contribute substantial additional information.

Estimating the net cost of resuming direct CSR payments and increasing the benchmark premium

The main text discusses a policy option under which policymakers would: (1) resume direct CSR payments; and (2) increase the benchmark premium that applies to enrollees who are not enrolled in generous CSRs by a percentage designed to approximate the increase in the benchmark premium under silver loading.

To estimate the cost of this package relative to current law, I begin by making two assumptions. First, I assume that this policy change would have no effect on the number of people who enroll in Marketplace coverage or the types of plans they select (although I relax that assumption below). Second, I assume that silver loading increases aggregate Marketplace silver premiums by an amount equal to the missing CSR payments.[23] Under those assumptions, the net cost of this package approximately equals the reduction in aggregate silver premiums paid by silver plan enrollees not receiving generous CSRs.[24]

To estimate that amount, I require two pieces of information about the world with silver loading: (1) the number of enrollees in silver plans without generous CSRs; and (2) the average silver premium for those enrollees. I discuss how I estimate each of these amounts in turn:

- Number of enrollees without generous CSRs: For states that use HealthCare.gov, the relevant number of plan selections can be extracted directly form CMS’ open enrollment public use file. For other states, I impute this amount by assuming that these enrollees account for the same share of silver plan enrollment as in HealthCare.gov states with the same Medicaid expansion status.[25] This yields an estimate of 1.5 million silver plan selections without generous CSRs out of 12.0 million total Marketplace plan selections in 2021. To project this estimate forward, I scale this 1.5 million estimate by the ratio of the total number of Marketplace plan selections in 2021 to CBO’s most recent projection of Marketplace enrollment in each future year.

- Average silver premium: For the HealthCare.gov states, this amount can be extracted directly from the open enrollment public use file. For other states, I assume that this premium equals the HealthCare.gov average for states with the same Medicaid expansion status.[26] This leads to an average monthly silver premium of $641 in 2021. To project this premium forward, I use CBO’s projections of growth in the average benchmark premium under current law.

From these two amounts, and under the assumption that silver loading increases silver premiums by 27.6% on average, I obtain an estimated average annual cost of $2.3 billion for the 2023-2030 period.

Relaxing the assumption that the policy would have no effect on enrollment would not meaningfully change the results. This policy would, by design, have no effect on the options available to people with incomes below 200% of the FPL, so it would not affect enrollment in that group. At higher income levels, it might spur current enrollees to change metal tiers or spur additional people to enroll. Shifts across metal tiers would have little effect on federal costs because the value of the premium tax credit is (almost) independent of the plan a person selects and because these people are not eligible for substantial CSRs. Any change in aggregate enrollment would likely be small because this policy would, by design, not change the net premium of bronze plans (unless there were larges changes in the risk mix of bronze enrollees).

In practice, this policy would likely be implemented in conjunction with making the premium tax credit enhancements in the American Rescue Plan Act (ARP) permanent. That would tend to increase the cost of this package, principally because Marketplace enrollment would be higher. CBO has estimated that the temporary ARP provision would increase Marketplace enrollment by 1.7 million at its peak in 2022, an increase of 20% over CBO’s prior projection of Marketplace enrollment. If a permanent version of the ARP policy increased Marketplace enrollment by 30% and this increase in enrollment proportionally increased the net cost of this replacement for silver loading, then the net cost of the silver loading replacement policy would be $3.0 billion per year over the 2023-2030 period rather than $2.3 billion per year.

Finally, I note that a crucial assumption underlying these calculations is that the share of total Marketplace enrollment accounted for by silver plan enrollees without generous CSRs would remain steady if silver loading continued. However, Figure 2 suggests that this group is on a path to shrink over time, in which case the long-run cost of this package of policies would be smaller than estimated here. Additionally since a portion of the increase in the benchmark premium caused by silver-loading may reflect utilization changes rather than the direct effect of ending CSR payments, it is possible that the cost of resuming CSR payments may be smaller than the aggregate reduction in silver premiums from ending silver loading, which would also cause the cost of this suite of policies to be somewhat lower than calculated here.

Differential between second-lowest-cost gold and silver premiums

The main text reports an estimate that the second-lowest-cost gold premium is 12% higher than the second-lowest-cost silver premium on average nationwide in 2021. I derive this estimate in three steps. First, I calculate the relevant average premiums in each HealthCare.gov state in 2021, weighting each average by county-level plan selections. Second, since premium data are not available in the needed form for the states that do not use HealthCare.gov, I impute average premiums for these states by assuming that they are the same as in HealthCare.gov states with the same Medicaid expansion status.[27] Finally, I compute a national weighted average, weighting each state by its total Marketplace plan selections.

Footnotes:

[1] American Indians and Alaska Natives are eligible for CSRs outside this income range. Those CSRs are more generous than the standard CSRs and are available on non-silver plans. Additionally, certain lawfully present immigrants are eligible for CSRs even if their income is below 100% of the FPL.

[2] At the time, I was also concerned that ending CSR payments would be harmful, as I was concerned that the transition to silver loading might be rockier and less durable than turned out to be the case in practice.

[3] Silver loading was explicitly encouraged or directed by state insurance regulators, with the exception of a handful of states that initially directed “broad loading” (raising premiums in all metal tiers). While insurers would likely have ultimately transitioned to silver loading on their own since their incentives naturally lead them to that outcome, regulators’ endorsement of silver loading likely substantially smoothed the transition.

[4] As discussed at length in the appendix, the aggregate increase in insurers’ premium revenue from Marketplace silver plans due to silver loading should approximately equal the aggregate amount of the missing CSR payments (holding enrollment fixed). Almost all enrollees in Marketplace silver plans receive the premium tax credit (95% in states using the HealthCare.gov platform in 2021, even before the expansion of the premium tax credit in the American Rescue Plan Act), so almost all of those additional premiums are borne by the federal government.

[5] A new CBO estimate could differ somewhat from this March 2018 estimate due to changes in CBO’s methods. Additionally, if the enhanced subsidies in the American Rescue Plan Act are made permanent, that would increase CBO’s projections of subsidized Marketplace enrollment and, thus, the savings from ending silver loading.

[6] Insurers could not stop offering silver plans entirely because insurers must offer at least one silver plan (and at least one gold plan) if they offer any Marketplace plans. See 42 USC 18021(a)(1)(C)(ii).

[7] See 42 USC § 300gg for the ACA’s community rating rules, which govern how an insurer can vary premiums across individuals. See 42 USC § 18032(c) for the ACA’s single risk pool requirement, which has been interpreted to bar insurers from accounting for risk mix in setting premiums of different plans (see 45 CFR § 156.80).

[8] Indeed, the fact that a non-trivial number of enrollees with incomes below 200% of the FPL opted for bronze plans prior to silver loading even though generous CSRs were only available on silver plans suggests that many Marketplace enrollees place too high a weight on premiums relative to cost-sharing. Research in the context of Medicare Part D has also found evidence that consumers overweight premiums relative to cost-sharing, although some research examining people with employer coverage finds consumers making the opposite error.

[9] These estimates are limited to HealthCare.gov states and were calculated using the 2021 Marketplace open enrollment public use file, which reports what share of silver plan enrollees are receiving each tier of CSR.

[10] States operating BHPs still capture the benefits of silver loading for people below 200% of the FPL since BHP payments are calculated as if all of the BHP enrollees were still enrolled in the Marketplace.

[11] In theory, the premium tax credit could also be used to steer enrollees to a specific metal tier. For example, enrollees who selected a silver plan could have their premium tax credit calculated using a more generous formula. Similarly, CSRs could, in principle, be made available in all metal tiers, rather than just the silver metal tier, although this would make delivering CSRs somewhat more complex for insurers. In practice, however, it is likely that premium tax credit enhancements would be available in all tiers and CSRs only in the silver tier.

[12] See the appendix for details on how this estimate and the estimates in the subsequent paragraph were derived.

[13] A number of other observers have also pointed to the factors discussed in the next paragraph in seeking to explain why gold premiums are higher than silver premiums under the status quo.

[14] If this policy was cheaper than continuing silver loading, subsidized enrollees would likely face higher premiums for bronze plans. Policymakers might want to use any leftover funds to address that fact.

[15] On the other hand, risk mix changes could also cause silver premiums to rise. However, this is not guaranteed; if the enrollees who shifted out of the silver tier and into the gold tier had a risk mix comparable to the average silver plan enrollee, then gold premiums could fall without silver premiums rising.

[16] See 2 USC § 907(b).

[17] In doing so, CBO has reasoned that silver loading is an alternative way of meeting the federal government’s obligations to insurers under the CSR program, so that this approach is consistent with the statutory requirement that the baseline assume the federal government meets its obligations under entitlement programs.

[18] This assumes that insurers are able set Marketplace silver premiums to reflect the costs in their Marketplace silver plans. This is a reasonable approximation as of 2021, as almost all states had blessed silver loading by 2019, and most applied silver loading only to Marketplace plans. Even where silver loading theoretically applies to off-Marketplace plans, very little of the total silver load is likely being applied to those plans since off-Marketplace silver enrollment is likely small (or held by insurers without much Marketplace business). In practice, silver loading may also occur even where it is theoretically barred given insurers’ strong incentives to silver load.

[19] I make an exception for the District of Columbia, Minnesota, and New York, where the population eligible for generous CSRs is covered by either Medicaid (the District of Columbia) or a Basic Health Program (New York and Minnesota). For these states, I impute an average actuarial value of 71.5%.

[20] I cannot apply exactly the same method in 2017 because the 2017 public use file does not report enrollment by CSR tier. Instead, I use data on silver plan selections by income group to impute what share of silver enrollees are eligible for each tier of CSR. (This method is exact except in the case of American Indians and Alaska Natives, who are eligible for a different schedule of CSRs, and the small number of lawful immigrants with incomes below 100% of the FPL who are eligible for CSRs.) I estimate that the average actuarial value of a silver plan was 83.8% in 2017 and 86.0% in 2021 and use these estimates to trend the main 2021 estimate back to 2017.

[21] See 45 CFR § 156.140 for the rules governing the actuarial value of plans without CSRs. See 45 CFR § 156.400 and 45 CFR § 156.420 for the rules governing CSR variants.

[22] An exception is that I do not apply the expansion state estimates to the District of Columbia, Minnesota, or New York for the reasons described above. Instead, I assume a silver loading effect of 1.9% (=0.9*[0.715/0.7]+0.1).

[23] This assumption will hold exactly in a simple competitive model with unconstrained silver loading provided that the transition to silver loading does not change utilization patterns in silver plans.

[24] In detail, observe that premium tax credit costs fall by the amount of the decline in silver premiums for people eligible for generous CSRs. The net of those savings and the cost of resuming CSR payments is approximately equal to the reduction in aggregate silver premiums paid by enrollees not receiving generous CSRs.

[25] Once again, I make an exception for the District of Columbia, Minnesota, and New York. For these states, I assume that all silver plan enrollment is in plans without generous CSRs.

[26] Here I do not make a special adjustment for the District of Columbia, Minnesota, and New York, although some such adjustment is likely appropriate. This will likely lead me to slightly overstate the average silver premium.

[27] Once again, some special adjustment for the District of Columbia, Minnesota, and New York would likely be appropriate, but I do not make one. This likely leads me to modestly understate the national gold-silver gap.

Acknowledgments:

I thank Kathleen Hannick for excellent research assistance and Brieanna Nicker for excellent editorial and web publishing assistance. I thank Loren Adler, Paul Ginsburg, and Richard Kogan for helpful comments on a draft of this piece.