Lessons learned from

expanded unemployment insurance

during COVID-19

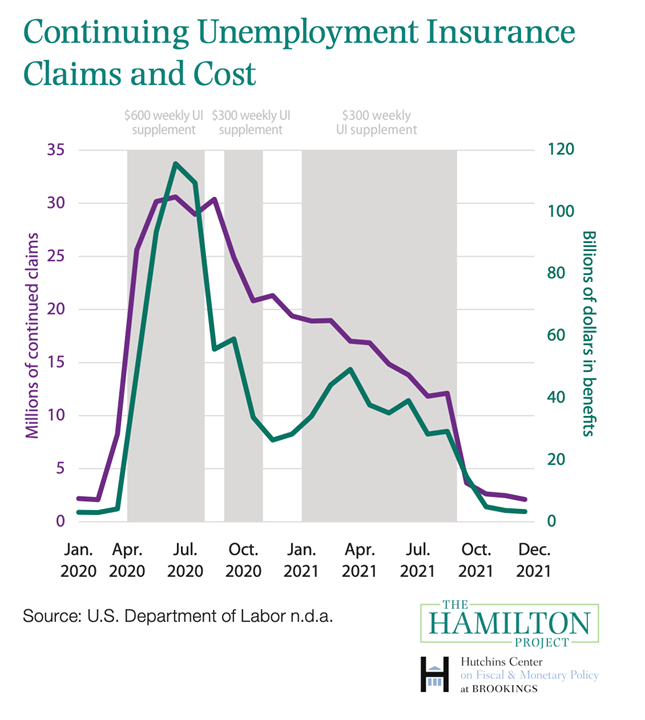

The COVID-19 recession was born out of a public health threat. Thus, unemployment insurance (UI) was meant to insure people against income losses associated not just with involuntary job loss, as in a usual recession, but also with the choice not to work due to the public health risk. Job losses were dramatic and concentrated in lower-paid in-person service sectors such as restaurants, leisure and hospitality, and retail. UI was just one of a variety of policies which provided direct assistance to households, including three rounds of Economic Impact Payments, debt forbearance, advance payment of the Child Tax Credit, and rent relief.

Prior to the pandemic, regular UI replaced just 50 percent of earnings in most states, and, as evidenced in low recipiency rates, many unemployed workers did not receive UI benefits. In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the U.S. government implemented the largest expansion of federal UI benefits in U.S. history. It increased the level of benefits through weekly supplements. Eligibility was expanded to include independent workers and those unable to work for a variety of COVID-related reasons through the Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA) program. The duration of federal benefits was extended by 53 weeks.

Recession Remedies podcast episode: How did expanded Unemployment Insurance affect the COVID-19 economy?

Evidence on the COVID-19 Economic Policy Response

What happened when the U.S. gave more people more money, and for longer? UI coverage increased, reaching workers who had historically been left out of the UI system, and boosting the spending of all UI recipients. But there were some comparatively smaller losses in efficiency, in the form of work disincentive effects and UI overpayments.

- UI expansions were highly progressive in that they offset income losses and delivered the most benefit to lower income workers.

- The spending impacts of UI were large. UI benefits provided a powerful stimulus to the macroeconomy by boosting consumption, particularly among low-income and low-liquidity workers.

- Work disincentive effects from UI benefits were small during the pandemic, especially when compared to historical standards.

- Through the PUA program, Congress increased access to benefits and insured income losses for workers on the margins of the labor market without clear evidence of greater work disincentive effects.

- The rapidly expanded UI programs faced a range of administrative challenges in meeting the surge in demand for benefits, including delays, unnecessary red tape, and overpayments, all of which were costly in terms of consumer welfare and government expense.

Lessons Learned from Expanded Unemployment Insurance during COVID-19

UI benefit expansions covered labor income risk not insured by regular UI, warranting consideration of adopting these more permanently or as automatic countercyclical stabilizers.

Temporary countercyclical UI supplements might be appropriate, especially during recessions when the risk of long-term unemployment is high. Although flat-dollar-amount supplements were highly progressive, flexible supplements that target a replacement rate likely create fewer inefficiencies in terms of work disincentives.

UI benefits provided a powerful stimulus to the macroeconomy by boosting consumption, particularly among low-income and low-liquidity workers.

A key challenge that states faced during the pandemic was establishing an entirely new program amid peak claims volume. Thus, keeping a permanent version of PUA has the important benefit of allowing states time to establish protocols and enhance systems to accommodate other populations of uncovered workers during non-peak times.

Stronger administrative systems are necessary for delivering timely and accurate UI benefits at scale in a worker-centered, recession-ready way. Given that UI plays a key fiscal stimulus role to mitigate a recession, its ability to deliver relief quickly is critical. And yet states faced delays in processing the enormous surge in UI claims and standing up the new PUA program. In response, many states relaxed third-party verification, which resulted in an increase in improper payments.

Flexible supplements require a stronger IT and administrative back end, however; IT and administrative shortcomings were a critical barrier to implementing such a policy during the pandemic. Investment in technology can expand the frontier of what is possible, enabling states to be more accurate in making payments at a given speed or to making payments faster while maintaining accuracy. The federal government could provide technology and data infrastructure that could enable not only flexible benefit levels set at a target income replacement rate, but also stronger, more seamless eligibility verification and fraud prevention.

For more information or to speak with the authors, contact: