From commitments to action:

Executive summary

Data Downloads

The business case for inclusive growth is not novel. Over the past decade, there have been countless reports and think pieces written to make the case plain to private sector leaders and economic developers. There is, however, a new sense of urgency among business leaders to tackle racial equity specifically and to acknowledge and utilize their power to disrupt the nation’s legacy of racism and promote a more just economy.

Prompted by the COVID-19 pandemic’s disparate impacts as well as widespread instances of racial injustice by police and citizens against Black Americans, a growing number of CEOs and private sector leaders have stepped up their support of Black communities through philanthropy and other actions. These actions must now go further, extending beyond philanthropy to include deeper changes in business practices in which investments in Black and Latino or Hispanic workers and entrepreneurs matter for businesses’ bottom lines and long-term economic prosperity. This is the new economic competitiveness agenda.

This report offers CEOs and CEO groups a three-part framework for action to make meaningful progress toward a more equitable economy, starting in their home regions. CEOs can: 1) adopt individual company actions on diversity, equity, and inclusion to demonstrate credible commitment; 2) act as a regional coalition of CEOs to deliver a multiplier effect on racial equity in local economies; and 3) use their influence as board members of civic organizations such as chambers of commerce and public-private partnership groups to champion change within local institutions and collaborations.

This report also provides new and existing data that can serve as regional performance metrics for CEOs interested in moving the needle on racial equity and equitable growth as a collective. These include metrics to improve the representation of Black and Latino or Hispanic residents in occupations at the center of the post-pandemic digital economy. As the demand for diversity in suppliers and services vendors grows, we offer data on how well Black and Latino or Hispanic entrepreneurs are represented in each region’s business ecosystem. We also provide data to inform income and wealth creation in underserved neighborhoods, which often have assets the marketplace has overlooked or devalued.

Every regional economy has a different starting point for improving the economic participation of Black and Latino or Hispanic talent. Rather than abstract commitments, the data in this report aims to root CEOs’ actions in the context of their home markets, so they can make tangible improvements toward shared prosperity.

The report closes with compelling business actions emerging across the country. There has been a surge of CEO coalitions for racial equity, signaling the seriousness of businesses that are trying to do better for stakeholders and the overall economy. These efforts ought not be fleeting. Rather than working in isolation, business communities can learn from one another to create better outcomes for their companies and the people in their regional economies, which, in turn, can bring the nation together. Considering the power that the private sector has in shaping local economies, the coordinated, intentional efforts of CEOs and regional business leaders—or lack thereof—will ultimately shape the arc of future growth and the course of history.

Introduction

“We are striving to forge a union with purpose. To compose a country, committed to all cultures, colors, characters, and conditions of man.”

These words from Amanda Gorman’s powerful Inauguration Day poem capture the critical work ahead. At stake is whether the soul of America stands for equal opportunity for all. This has been a generations-long battle, with racial injustice long existing as de jure and de facto realities. The murder of George Floyd and other Black Americans last summer finally galvanized large swaths of the public to demand change.

To create a more perfect and inclusive union ought not rest on government solutions alone. This moment requires collective responsibility across multiple sectors of civil society. Among them, the business sector stands out. For one, the public is increasingly holding the private sector accountable for producing an economy and society that works for all people, including by taking actions against racial injustices.

Mellody Hobson, co-CEO of Ariel Investments and chair of Starbucks’ board of directors, argues that the current racial reckoning marks the third chapter in the nation’s civil rights struggle—and that this moment “has landed at the feet of corporate America.” While government formalized emancipation in 1863 and enacted landmark civil rights laws in the 1960s, this “Civil Rights 3.0” requires business to change. As stewards of the economy, business executives must address structural racism head on, including by acknowledging their role in perpetuating it.

This moment also requires more than national-level actions by large companies. There must be demonstrable progress for Black and Latino or Hispanic communities in the regions where firms do business and where workers and families seek opportunities. Some of these cities may have made headlines in recent years: Minneapolis (George Floyd), Louisville, Ky. (Breonna Taylor), Baltimore (Freddie Gray), Chicago (Laquan McDonald), Cleveland (Tamir Rice), Sacramento, Calif. (Stephon Clark), St. Paul, Minn. (Philando Castile), and St. Louis/Ferguson, Mo. (Michael Brown). But all metro areas, large and small, can do more to address the systemic discrimination and unequal opportunity that have failed people of color.

To that end, when CEOs work in concert with other executives in their home markets and in partnership with public schools, community colleges, local governments, philanthropy, transportation providers, and others, they can exert even greater influence on systemic solutions that meet the needs of families, workers, and employers in achieving a stronger economy and society. This kind of collective action would create greater change than any one commitment by an individual firm.

To its credit, the business sector has stepped forward. CEOs of some of the nation’s largest companies have begun a long overdue examination of their own practices, taken concrete action to advance racial equity, and started to embrace the tenets of stakeholder capitalism, which looks beyond shareholder interests and recognizes the needs of diverse customers, employees, suppliers, and communities as critical to long-term success. Furthermore, coalitions of CEOs in cities and metropolitan areas have approached Brookings Metro seeking ideas on what they can do to create a racially equitable economy. Their interest has not waned, even as national headlines on this topic have.

With twin demands to rebuild for the post-COVID-19 economy and address racial injustice, business executives can pave the way toward a more equitable economy, especially in their home regions. This report provides a three-part action framework for CEOs in regions to do just that. This includes recommendations for CEOs within their headquarters regions to act as a collective, setting goals and benchmarking progress on key performance indicators by race, ethnicity, and metro area. The report concludes with examples of promising private sector initiatives on racial equity and a just economy that we hope can inspire others.

The case for more private sector action

Since the summer of 2020, major corporations have stepped up their commitments to racial justice. By one count, the nation’s 1,000 largest firms have pledged $66 billion in total contributions to racial justice causes. Companies such as Netflix and JPMorgan Chase have announced bold initiatives to invest in Black communities and tackle systemic racism. And through the Business Roundtable, over 200 of the nation’s largest companies have joined forces with a pledge to close the racial opportunity gap through policy changes in employment, housing, finance, education, health, and criminal justice.

Business executives can build on these important early efforts by putting greater emphasis on internal practices and actions that may hold promise for tangible improvements in communities.

Shifting from a charity mindset to good economic sense

While corporate giving is essential, it is insufficient. As our colleague Andre Perry wrote, “We’re not going to ‘nonprofit’ our way out of poverty, housing unaffordability and economic injustice.” The market needs to work for more people.

To start, business leaders must not view Black Americans through a charity mindset or as “social” problems to be solved. The vast majority of Black Americans simply want good jobs, economic dignity, and a fair shot at upward mobility. One prominent survey of 30,000 Black Americans, led by Black Futures Lab, found that the number-one issue among those polled—even more pressing than police brutality—is that Black workers’ wages are too low to support their families. Black workers are disproportionately relegated to low-wage jobs, including frontline essential occupations in retail, home health care, and meatpacking industries, which puts them at risk of COVID-19 exposure for little pay or no health benefits. Black workers are also highly underrepresented in the good-paying, growing digital jobs of the future, many of which do not require workers to have a college degree.

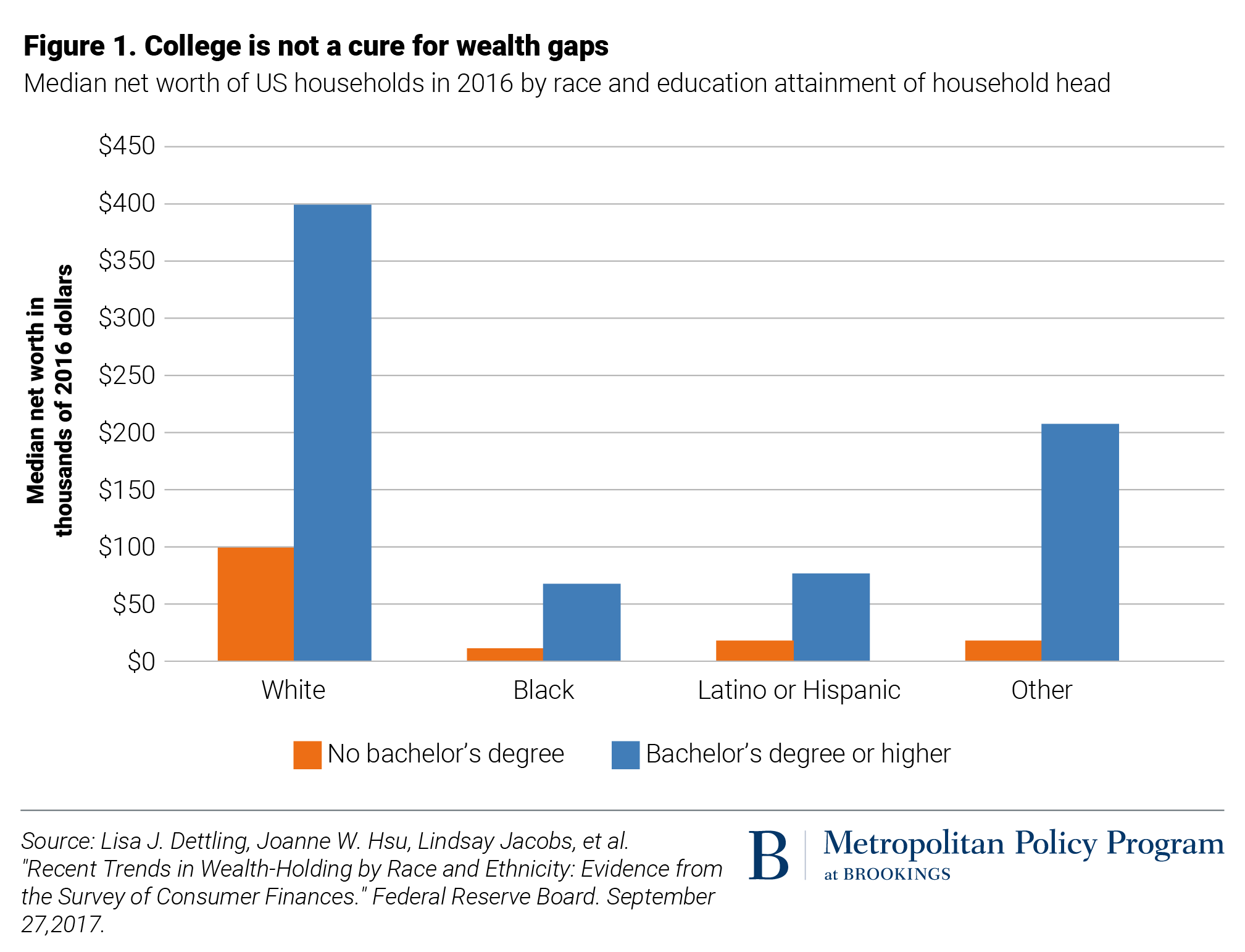

It’s also worth pointing out that the prevalence of low incomes and low wealth among Black and Latino or Hispanic workers is not because these workers simply need more education. As this chart produced by Brookings’s Richard V. Reeves shows, Black and Latino or Hispanic heads of household who have a college degree still have dramatically less net wealth than heads of white households (Figure 1). In other words, even when Black and Latino or Hispanic workers play by the same economic rules as white workers, they are not rewarded. This is why statements by CEOs claiming that there is not enough Black talent show that racism and systemic marginalization still permeate the marketplace, and must be undone.

Chief executives must shift their mindsets. Adopting the theory of stakeholder capitalism, they should embrace often-overlooked Black and Latino or Hispanic talent, consumers, businesses, and communities as assets that contribute to company bottom lines and power local economies. There is plenty of evidence that proves companies gain when doing so. For instance, companies with greater racial and gender diversity in their management teams and boards are more likely to outperform and out-profit their peers. These companies often create organizational cultures where staff feel comfortable proposing novel ideas, which makes them more likely to introduce new product innovations that appeal to wider, more diverse audiences—thus increasing overall competitiveness and improving financial performance.

Companies that commit to a culture of diversity and inclusive belonging are also more likely to attract and retain talent. A survey conducted by The Harris Poll on behalf of job site Glassdoor found that 76% of job seekers consider diversity an important factor when evaluating companies and job offers. And as the workforce increasingly becomes less white over time, intentionally hiring people of color and supporting an inclusive workplace will become even more imperative. This will improve bottom lines and allow regional economies to prosper as companies embrace the business case for diversity, equity, and inclusion and reap their benefits.

Beyond philanthropy to business practices

The shift from social to economic motivations also means that business leaders need to adopt more authentic changes in corporate practices—not just expand their philanthropy.

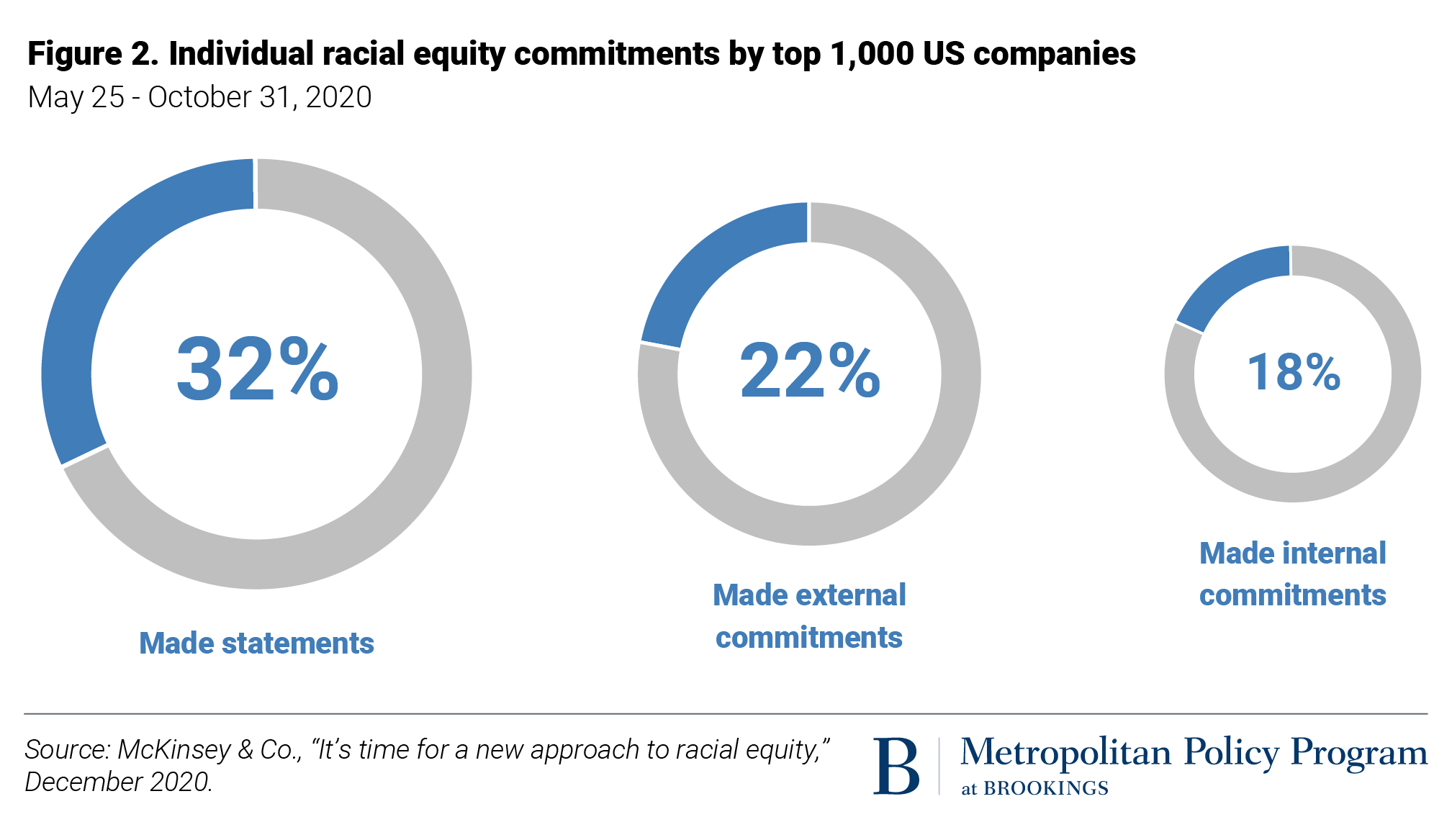

The group CEO Action for Diversity & Inclusion has been helping executives make workplace reforms since 2017. However, several notable reports find that corporate America, including big tech companies, are still falling short on their commitments to racial equity and stakeholder capitalism more broadly. A McKinsey & Company review of the 1,000 largest U.S. companies found that most corporate commitments to racial justice have yielded greater levels of philanthropy but fewer internal changes, such as board composition, hiring, and procurement (Figure 2).

A comprehensive review of stakeholder capitalism found that business rhetoric remains ahead of company performance in elevating the needs of other stakeholders beyond shareholders. In other words, companies have yet to make enough demonstrable improvements for their workers, customers, suppliers, the environment, and local communities.

We would add that CEO commitments should come from a greater number of executives. There ought to be leadership from those at the helm of large global firms, small and midsized employers, and venture-backed startups that, together, anchor many local economies. We also believe that company executives can exert wider and more systemic impact when their internal changes are made collectively in regions in coordination with other firms and nonprofit and public sector partners. There’s greater “return on investment” when individual actions are matched by others, with each entity doing its part to expand equity and opportunity at scale across a community.

In many cities and metro areas, CEOs are stepping up through existing regional CEO councils or as members of CEO groups, such as the Columbus Partnership or the Civic Council of Greater Kansas City. Others are forming new coalitions, such as the Corporate Coalition of Chicago or the Minnesota Business Coalition for Racial Equity. (More on these and other efforts in the “Emerging Models” section.)

In short, it is time for business executives to act with greater intention to value Black and Latino or Hispanic communities. This includes diversity, equity, and inclusion actions within the workplace and as coalitions within our regions and neighborhoods, as the CEO of Redfin recently argued.

To not act in this moment is to affirmatively decide to maintain a status quo perpetuating conscious and unconscious bias that has held Black and Latino or Hispanic people back and deprived them of good economic opportunities.

A framework for action

When asked what business executives in cities and metro areas can do to advance racial equity and an equitable economy, we offer this three-part framework. In sum, private sector leaders can:

- Adopt internal changes within individual companies to promote diversity, equity, and inclusion

- Act collectively with other CEOs to make regionwide progress on racial equity and equitable growth, including improving key regional performance indicators

- Encourage business-led civic organizations to adopt their own changes toward equity and inclusive economic growth

Adopt internal company changes on diversity, equity, and inclusion

To start, individual chief executives can undertake an internal audit of their companies’ diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) performance to ensure any public commitments to a just economy start from within.

There are a number of valuable resources for business executives in this regard, such as this CEO blueprint for racial equity and this diversity, equity, and inclusion solutions audit aimed at firms in the tech, startup, and venture ecosystems. The audit is informed by a framework advanced by Rodney Sampson of Opportunity Hub, who has worked with startups, scale-ups, venture funds, and large tech firms to ensure that DEI is operationalized across their businesses and company cultures. The seven-part strategy for employers includes a review of the extent to which DEI is operationalized in corporate boards and governance; among hiring, promotion, and HR practices; in corporate procurement and vendor services; in corporate innovation and product development, so firms are developing ethical products and solutions that meet the needs of a more diverse customer base; in the resources firms place on going to market and reaching more diverse audiences; and in the way firms invest in and empower Black and Latino or Hispanic businesses, programs, and communities through equity investments, partnerships, and philanthropy.

When chief executives demonstrate their own work to dismantle bias and create a culture of true belonging, it provides a level of trust and credibility needed for these firms and leaders to collaborate with others in bringing about broader progress and sustained prosperity in their home regions.

Act collectively to make regionwide progress on racial equity and equitable growth

CEOs should form a coalition of peers in their home region to collectively advance DEI metrics in at least one of three common areas of focus: training and hiring diverse talent, minority business growth and supplier diversity, and neighborhood wealth-building. Rather than work individually and ad hoc, these private sector executives could coordinate their actions in communities with other CEOs and key nonprofit and government partners. Doing so would pool risks and resources. Collective action would also exert a stronger impact on the systems (such as in workforce training, business capital, land use, and real estate) that currently create structural advantages and disadvantages in communities.

For example, per the data offered later in this paper, CEOs in a region could commit to increasing the share of Black and Latino or Hispanic workers in management or computer/science occupations. CEOs could set a target that makes sense in their region, such as growing the share of Black managers or in-demand tech talent to match, at minimum, their proportionate representation in the workforce. To do this, they could partner with area business schools, community colleges, or historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs) like Morehouse College and others who regularly offer computer science degrees or full-stack software development training programs to meet the needs of employers. The region would then have a system for grooming a steady supply of diverse, next-generation talent that makes the region an attractive place for young professionals and industries.

Encourage business-led civic organizations to adopt their own changes toward equity and inclusive economic growth

Many CEOs are part of business-oriented civic groups such as CEO-only alliances, chambers of commerce, economic development organizations, and public-private partnerships that are forming in many communities, including the Greater Washington Partnership and Greater Seattle Partners. These organizations have the charge of growing local economies and, increasingly, the inclusive economic growth agenda by bringing together the business sector and other community partners (e.g., nonprofit, government, philanthropy, universities) toward that end.

One advantage these groups have is the established structure and networks to effectively facilitate a regional agenda for racial equity. Yet, these groups need to continue to evolve their metrics, partnerships, and programs to be authentic facilitators of an equitable economy. Oftentimes, these organizations’ staff are eager to be race-forward, but they need the blessing and support of their leadership and board. CEOs can not only endorse but proactively encourage these civic entities to embrace racial equity and economic inclusion as part of their mission and regional economic agenda. In fact, in many cities and metro areas, these “establishment” organizations can bring more leaders of color into their organizational ranks, diversify their civic tables, and empower Black- and Latino- or Hispanic-led organizations to take the lead in driving communitywide initiatives with business backing.

Key metrics to benchmark regional progress

Of the three actions above, we believe CEOs have a huge opportunity to not operate alone, but in collaboration with other CEOs and partner organizations to address racial equity and equitable growth more systemically while making needed changes internally.

One thing we’ve learned in engaging CEOs, business groups, and the real estate sector is that collective actions become more tangible and actionable when they are tied to regional performance metrics. In fact, many regional civic organizations have developed regional dashboard or indicator projects to ensure they are making measurable progress toward an equitable economy.

What follows is a sampling of new and forthcoming metro area analysis that CEOs can use in the development of regional key performance indicators (KPIs) in four areas:

- Improving Black and Latino or Hispanic representation in management positions across local companies

- Improving Black and Latino or Hispanic representation in tech occupations that represent fast-growing parts of the economy

- Investing in Black and Latino or Hispanic businesses, suppliers, and vendors

- Expanding income and wealth creation in overlooked neighborhoods

These indicators can inform quantitative goal setting within each, including benchmarking of progress along the way. These four areas also match most of the stakeholders that matter to stakeholder capitalism, in which the needs of workers, suppliers, and local communities become more central.

What follows are potential areas to move the needle toward tangible progress in racial equity and equitable growth in cities and metro areas.

Improving Black and Latino or Hispanic representation in management

As mentioned earlier, companies that have diverse boards and leadership teams outperform their peers in product development, revenues, return on investment, and staff engagement. Having visible leaders of color within a company also helps with attracting and retaining talent. Black leaders in management positions, for instance, are likely to decamp to other companies with more supportive environments if they feel they are “alone” in climbing the corporate ladder. And many young professionals today are prioritizing workplaces with strong DEI cultures.

Improving Black and Latino or Hispanic representation in management positions is not only good for individual companies and nonprofits, but is also good for the region. It expands the pool of Black and Latino or Hispanic talent that can move into higher positions of leadership, both within businesses and on civic boards and committees. It also diversifies professional networks across the region, providing visible role models, mentors, and champions for next-generation talent.

Therefore, a coalition of chief executives in a region could commit to expand the ranks of Black and Latino or Hispanic talent in management positions across all sectors. These go beyond C-suite positions and include midlevel managers, such as those in human resources, finance, marketing, and distribution.

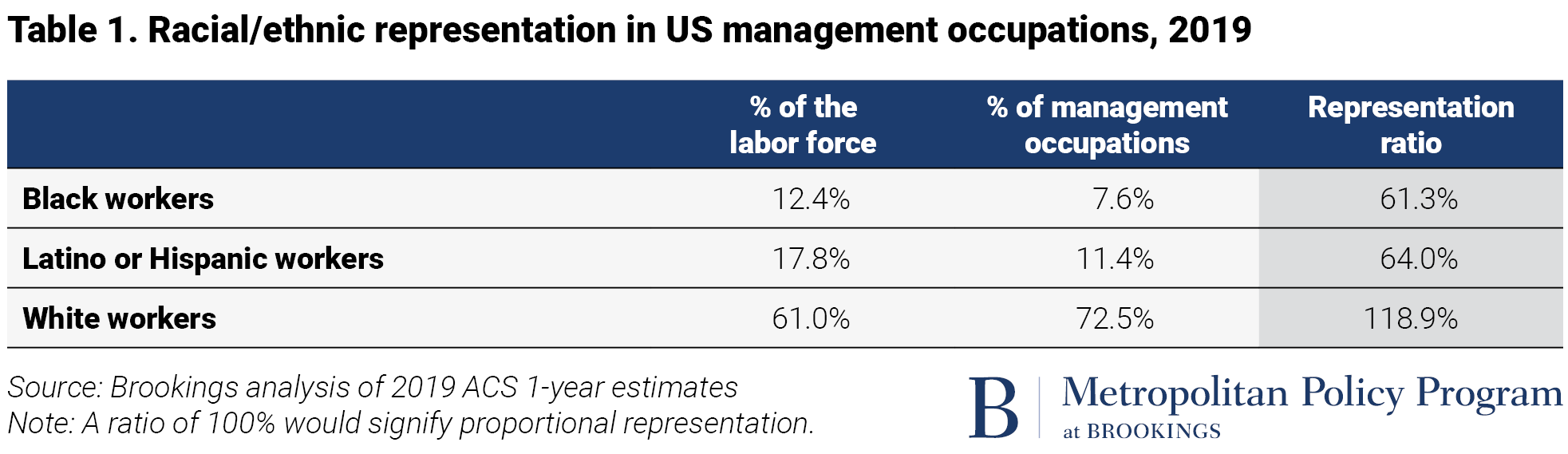

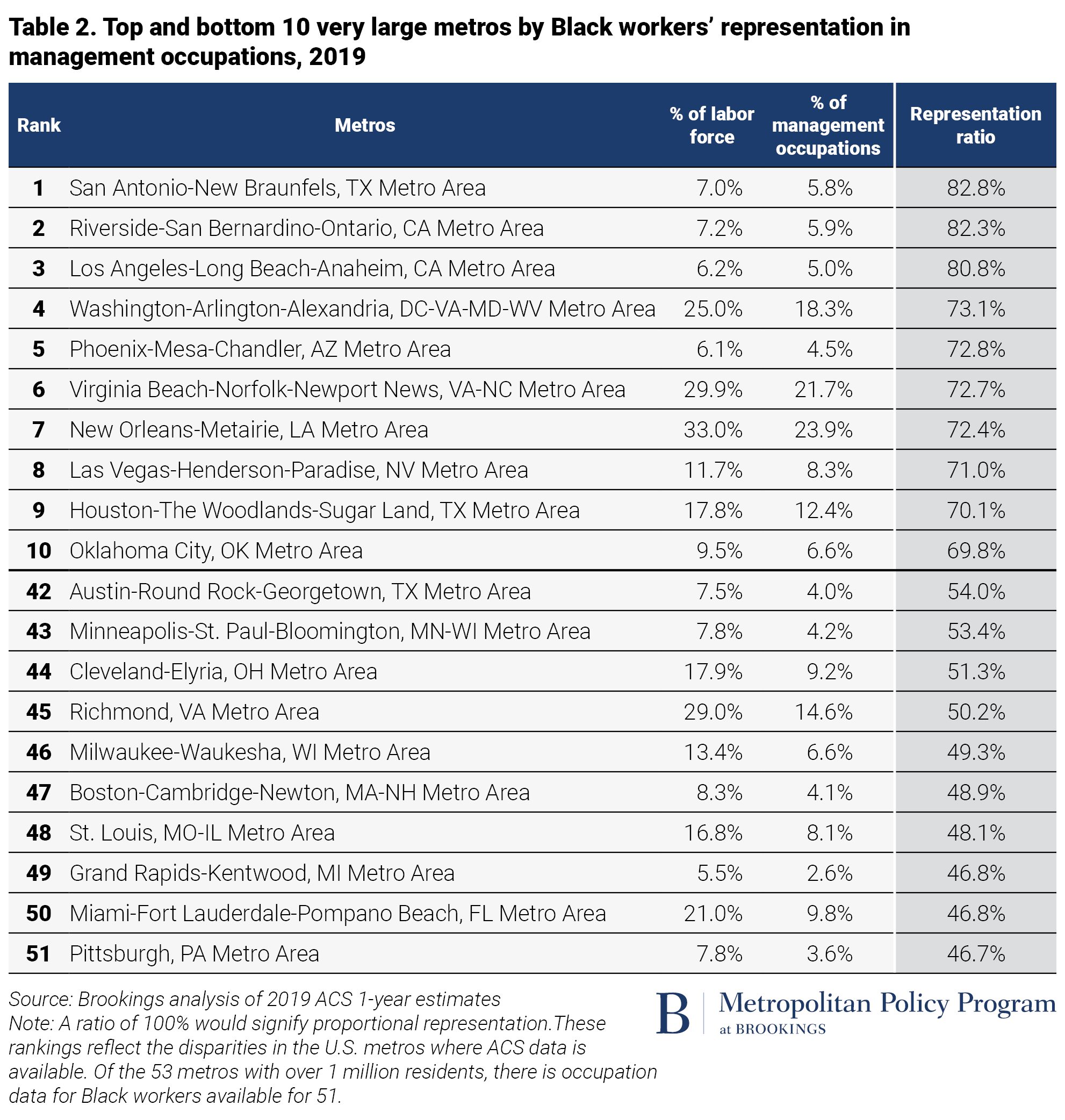

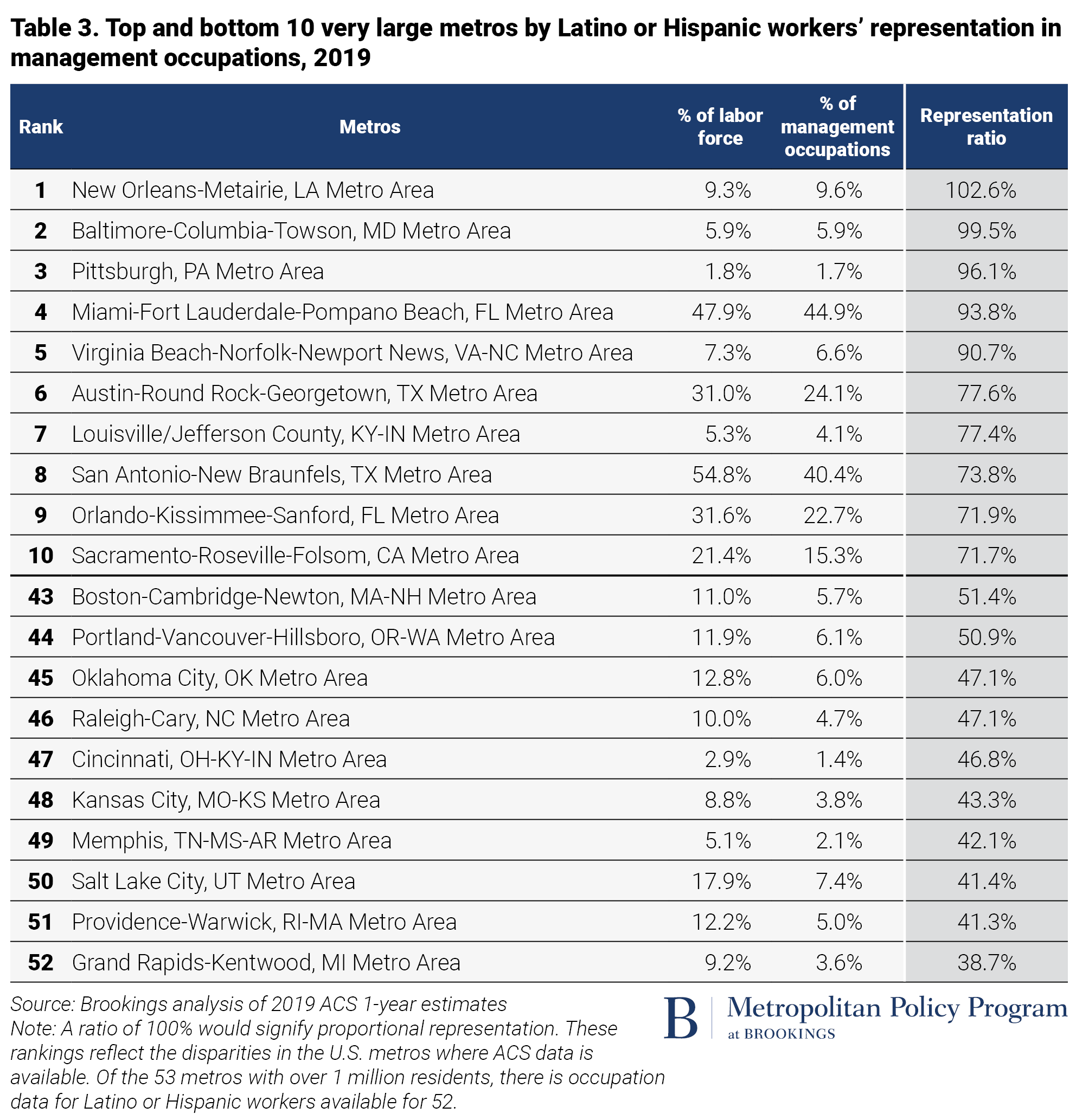

Despite all the aforementioned benefits, Black and Latino or Hispanic workers are highly underrepresented in private and public sector management positions, nationally and in key metro areas around the country. As Table 1 shows, Black workers currently make up 12.4% of the U.S. labor force, yet occupy only 7.6% of management positions. The percentage point gap is even larger for Latino or Hispanic workers, who are 17.8% of the U.S. workforce but merely 11.4% of all managers. White workers, on the other hand, are overrepresented, with 72.5% in management roles while making up 61% of the labor force—evidence of the systematic exclusion of Black and Latino or Hispanic workers from influential positions of leadership and decisionmaking.

For white workers, the representation ratio is 118.9%, which indicates that white workers are 18.9% overrepresented in management occupations relative to their share of the overall workforce. Meanwhile, Black workers are the most underrepresented in management roles, with a representation ratio of 61.3%. The closer the ratio is to 100%, the better the racial or ethnic representation is in any given metro. But when it exceeds 100%, it indicates overrepresentation. Note that the representation ratio should not be considered zero-sum. Less inequality spurs more growth, creating new opportunities for all workers, especially in occupations that are expanding.

Beneath the national picture, there is great variation among metro areas in providing Black and Latino or Hispanic talent the opportunities to access management positions.

Among the very large metro areas for which we have data (very large meaning that the population exceeds 1 million), there is not a single metro area in which Black workers are proportionately represented in management roles (Table 2). San Antonio and Riverside, Calif. come the closest with representation ratios of 82.8% and 82.3%, respectively. Both the greater Washington, D.C. and New Orleans areas have high shares of Black workers in their labor force and management occupations, placing these two regions among better performers in their representation ratios. But there is still room for improvement.

The worst-performing metro areas in proportionate representation of Black workers in management run the gamut from older industrial metro areas such as Pittsburgh, St. Louis, and Cleveland to innovation centers such as Boston, Minneapolis-St. Paul, and Austin, Texas. For the six worst-performing metro areas (Pittsburgh, Miami, St. Louis, Boston, Milwaukee, and Grand Rapids, Mich.), even doubling the share of Black managers in their regions would still fall short of achieving representational parity.

Private and public sector executives and managers should also reflect on the growing population of Latino or Hispanic Americans, who have contributed over half of the nation’s population growth in the last decade. Among the same very large metropolitan areas, this group is underrepresented in all except one where data is available (Table 3). New Orleans is the one labor market where the share of Latino or Hispanic workers in management occupations is greater than their share of the overall workforce—a representation ratio of 102.6%.

Baltimore and Pittsburgh have some of the most inclusive markets for Latino or Hispanic management workers, with nearly perfect representation—although the shares of Latino or Hispanic workers overall in those places are quite small (smaller than the national share). Meanwhile, a number of Sun Belt metro areas with high shares of Latino or Hispanic workers overall (Miami, San Antonio, Orlando, Fla.) also rank among the top metro areas in management representation.

Grand Rapids, Mich., Providence, R.I., and Salt Lake City are among the metro areas that fare the poorest on Latino or Hispanic representation, with representation ratios even worse than the lowest-performing metro areas for Black representation in management roles.

This data on representation in management roles by race and ethnicity can inform the development of regional performance targets for coalitions of local CEOs and their community partners. Leaders can examine the data against their local context, formally assess why there is underperformance not just within individual firms but also across the larger labor market, and set goals accordingly based either on shares or proportional representation by race and ethnicity. The exercise can also inform strategies that can be adopted within partner companies and ecosystem actors, such as the provision of management training or professional development opportunities at scale. Additional data—including the representation of other racial groups in management roles—can be found for very large (populations over 1 million) and large (populations between 500,000 and 1 million) metro areas for which we have data in the attached Appendices A and B.

Improving Black and Latino or Hispanic representation in tech occupations

Another way CEOs can demonstrate a commitment to diverse workplaces and an equitable economic recovery is to invest in the training and hiring of Black and Latino or Hispanic workers in new jobs in the digital economy. As COVID-19 accelerates the demand for digital platforms and the workers to support them, there is an opportunity for local area leaders and employers to set goals to increase the representation of Black and Latino or Hispanic workers in the economy’s growing tech occupations. Doing so would, in turn, offer upward economic mobility for Black and Latino or Hispanic workers and their families, as our colleagues have written.

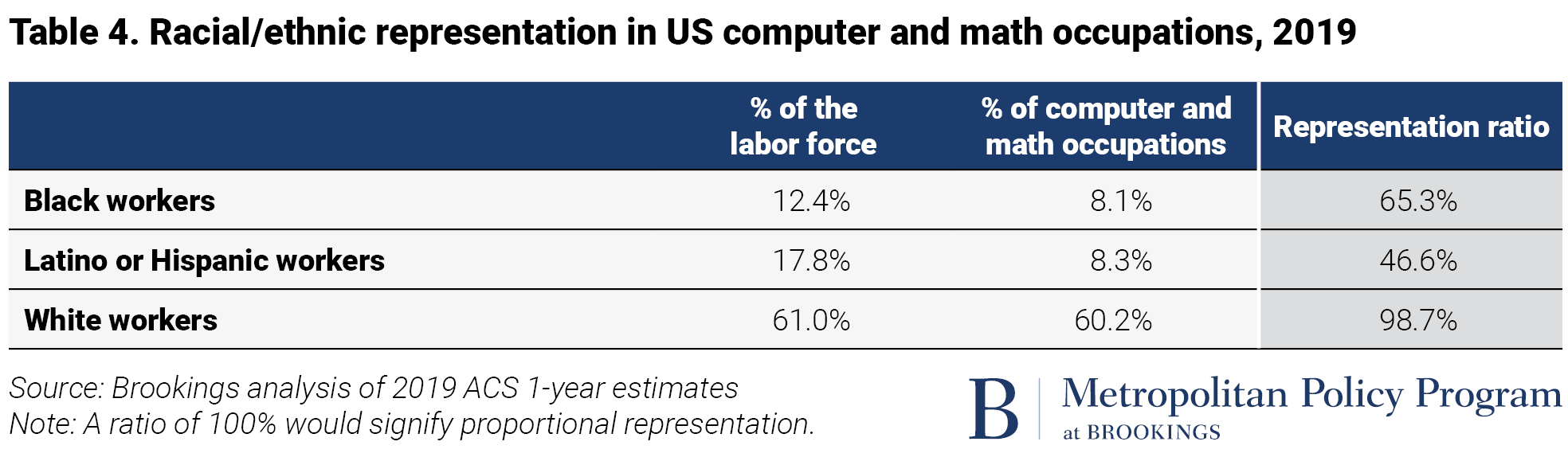

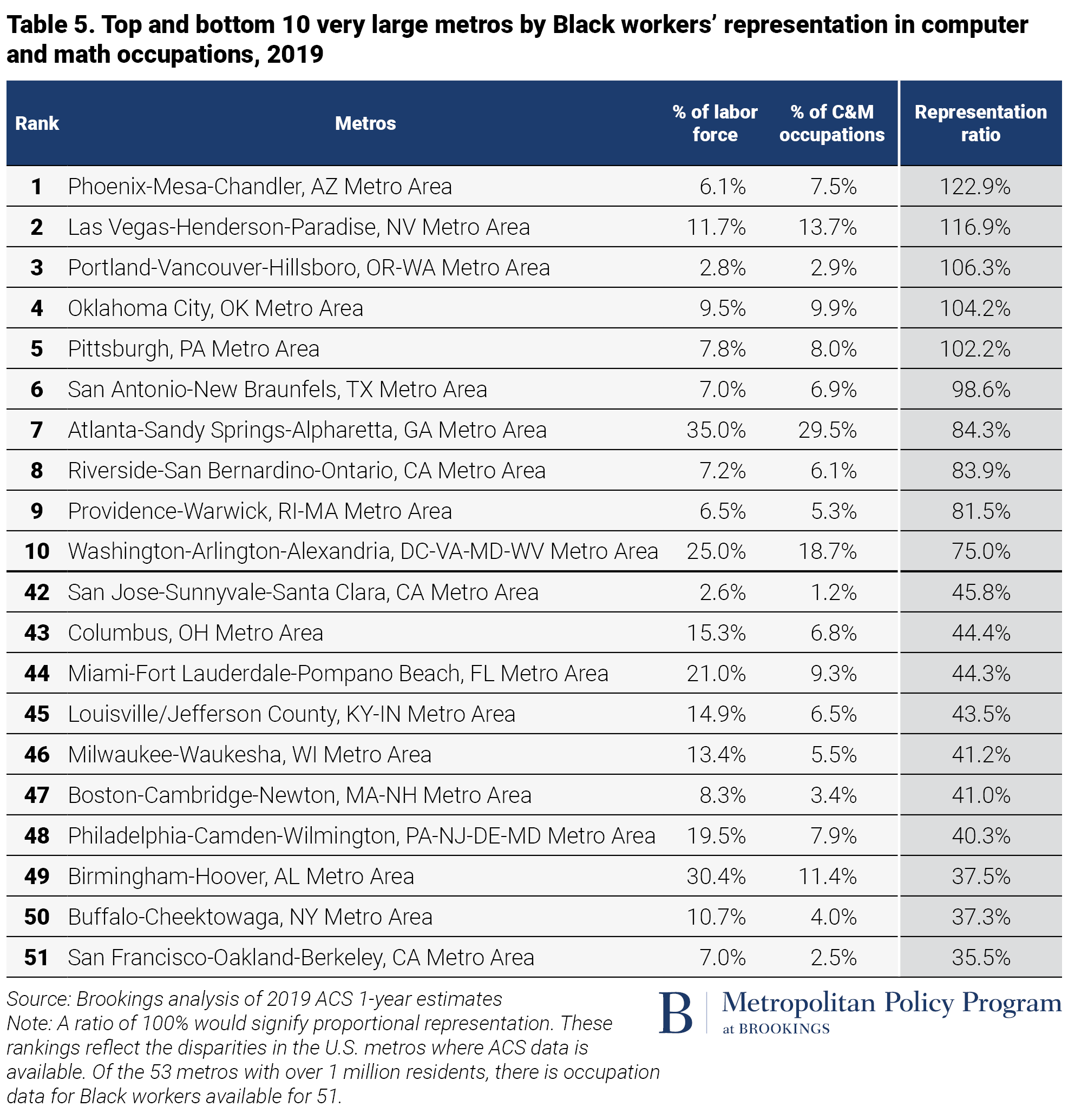

From 2010 to 2019, the U.S. experienced a 52% growth in the number of computer and math occupations, which include white-collar jobs such as software developers as well as more accessible mid-tech jobs such as computer support specialists. Yet, Black and Latino or Hispanic workers remain disproportionately excluded from these opportunities. Nationally, the representation ratios for Black and Latino or Hispanic workers are 65.3% and 46.6%, respectively (Table 4).

Just like with management roles, regional business communities can lead the charge in closing the national representation gap by setting quantifiable goals that resolve their areas’ unique disparities. Five very large metro areas are strong performers in providing job opportunities for Black computer and science workers: Phoenix, Las Vegas, Portland, Ore., Oklahoma City, and Pittsburgh (Table 5).

At the same time, however, three of the five “superstar” regions that drive the growth of the nation’s innovation economy rank in the bottom 10 on proportional representation for Black workers. San Francisco is the worst, with a 35.5% representation ratio; Boston ranks fifth worst, with a 41% representation ratio; San Jose, Calif. ranks 10th worst, with a 45.8% representation ratio.

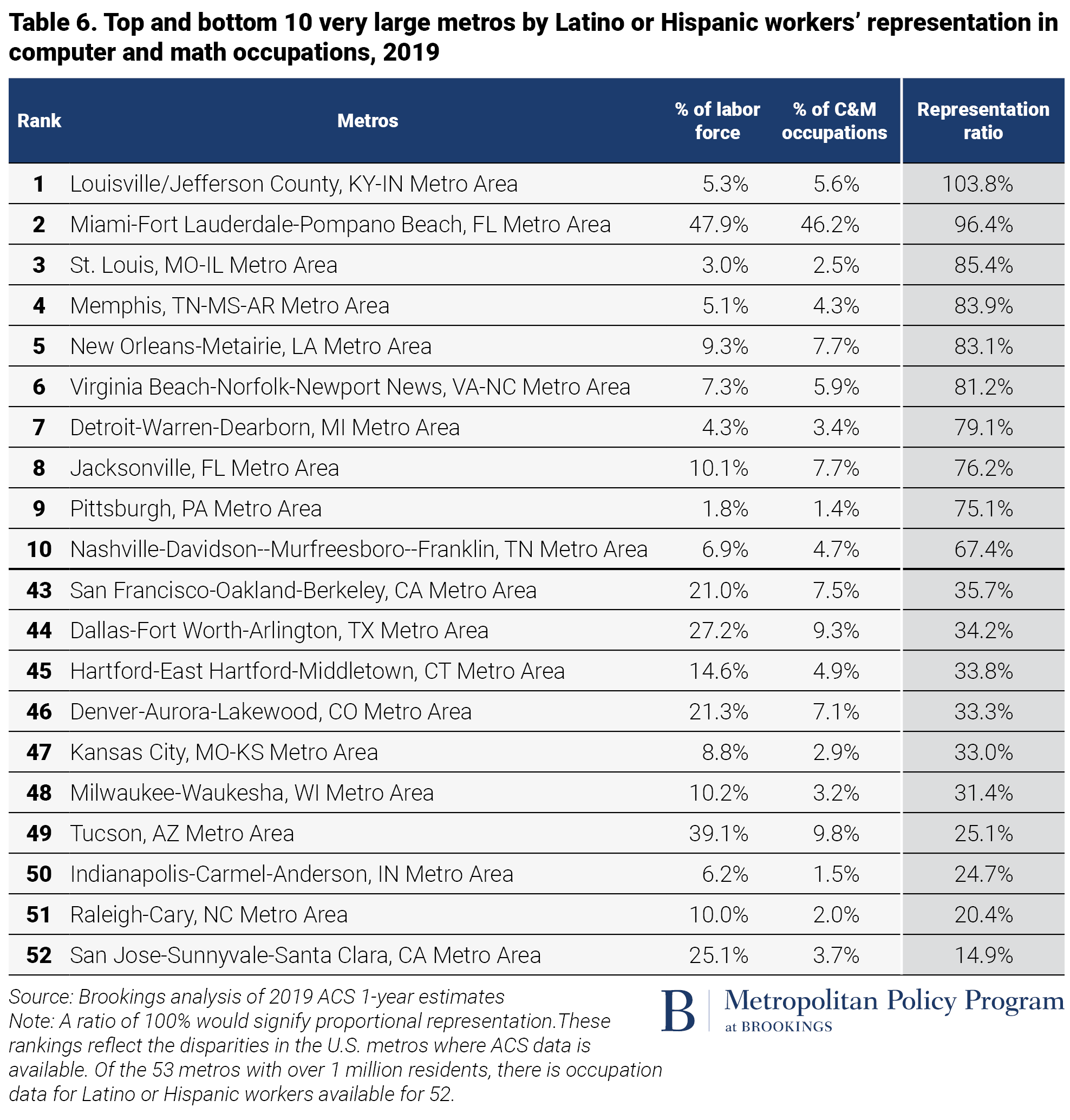

Latino or Hispanic workers are underrepresented in computer and math occupations in all but one very large metro area: Louisville, Ky., which has a representation ratio of 103.8% (Table 6). Louisville also ranks in the top 10 very large metro areas for Latino or Hispanic representation in management occupations. Other metro areas that rank among the top 10 most inclusive places for Latino or Hispanic tech workers include highly Latino- or Hispanic-centric metro areas such as Miami, and others with emerging shares of Latino or Hispanic workers, including Virginia Beach, Va., New Orleans, and Nashville, Tenn.

As noted earlier, Latino or Hispanic workers are highly underrepresented in rapidly growing digital occupations nationally, with a representation ratio of just 46.6%. In the low-performing metro areas, the proportionate underrepresentation of Latino or Hispanic workers in tech jobs is quite startling. The superstar tech hubs of San Jose, Calif. and San Francisco are in the bottom 10, as they were for Black representation. San Jose performs the worst of all very large metro areas, with a mere 3.7% of computer and math jobs being filled by Latino or Hispanic workers, even though one in every four workers in the region is Latino or Hispanic—a rather dismal representation ratio of 14.9%. San Francisco ranks 10th worst, with a 35.7% representation ratio.

Taking steps toward closing regional representation gaps starts with setting well-informed goals that use data on the current gaps to measure how much progress needs to be made. If a metro region like Denver or Milwaukee, for example, were to work toward tripling their share of Latino or Hispanic workers in computer and math occupations within a certain time frame, it could achieve almost proportional representation for their economies. Available computer and math occupation data can be found in Appendices C and D for very large and large metro areas. This data, which includes information on other racial groups, can assist regional multisector partners in using local metrics to set their goals.

Investing in Black and Latino or Hispanic businesses, suppliers, and vendors

To date, procurement goals to support women- and minority-owned businesses have primarily taken place within government and higher education. Yet, private industry has an enormous opportunity to forge new business relationships with entrepreneurs of color through the supplies and services they procure. This would bring new ideas and culturally diverse products and services to companies that match the preferences of their increasingly diverse workforce and customers. This would also expand wealth creation opportunities for Black and Latino or Hispanic business owners and their employees.

One way to benchmark progress is to ensure there is an ample pipeline of Black- and Latino- or Hispanic-owned firms in the region with the right mix of products, services, and capacities to partner with larger incumbent firms. As a starting point, leaders could examine the extent to which their city or metro area cultivates an inclusive startup and scale-up ecosystem for Black and Latino or Hispanic entrepreneurs, whether they are owners of small, local-serving businesses or midsized businesses in key traded sectors.

Regarding Black businesses specifically, our colleagues Andre Perry and Carl Romer have found that while Black people make up 14.2% of the national population, only 2.2% of the nation’s 5.7 million employer businesses are Black-owned. The typical Black business also earns one-sixth less in revenue than the typical non-Black business, at approximately $1.03 million per year versus $6.48 million. Still, Black entrepreneurs are doing business in vital sectors, such as health care and social assistance (32% of Black-owned firms) and professional, scientific, and technical services (13% of Black-owned firms)—the top two industries for Black businesses.

For local leaders, we have data for the 112 metros areas for which data is available on Black businesses. Perry and Romer’s report reveals that Black-owned businesses are vastly underrepresented in metro areas everywhere, but representation varies by place (Table 7). St. Louis and El Paso, Texas stand out for having significantly better representation of Black-owned businesses compared to other regions, with a 55.6% and 43.1% representation ratio, respectively. From there, representation ratios drop dramatically, ranging between an estimated 6% and 26%. Several southern metro areas with sizeable Black populations place in the bottom 10, including Tuscaloosa, Ala. (6.9%), Shreveport, La. (7.9%), Mobile, Ala. (8.3%), Florence, S.C. (8.5%), and Savannah, Ga. (8.8%).

A forthcoming report by Perry and Romer will provide additional analyses at the metro area level, including revenue levels and job creation for Black and non-Black businesses. These are stronger indicators of the size of Black-owned businesses and the missed opportunities in grooming them to forge vendor and supplier relationships with larger companies.

The hope is that investments in a vibrant, diverse business ecosystem will increase the share of minority-owned employer businesses and lead to real changes in corporate supplier diversity, which remains diminutive nationally. While the data is thin and often proprietary, one national report found that only 3% of Fortune 500 procurements benefited Black businesses, even though these partnerships have proved valuable for companies such as General Motors.

Rodney Sampson of Opportunity Hub often reminds big firms that Black entrepreneurs don’t simply want access to capital, they also want “access to contracts.” Enduring business-to-business relationships are key to growing Black and Latino or Hispanic businesses and centering their expertise in future growth. Thus, CEO actions to diversify procurement and support intermediaries that provide technical services to small businesses can yield a more inclusive and dynamic business ecosystem.

Expanding income and wealth creation in overlooked neighborhoods

Some business leaders (and their local mayors) have also come under pressure to make more visible commitments to neighborhoods—not just downtowns—and ensure economic opportunity is not limited to the favored quarters of the region. These business leaders recognize that stronger neighborhoods improve social cohesion and community trust at a time when racial tensions have intensified.

Several Brookings reports have shed light on how private sectors actors have systematically undervalued majority-Black neighborhoods with clear market assets and incomes. For example, homes in majority-Black neighborhoods are valued less than similar homes in non-Black neighborhoods. Highly rated businesses in majority-Black neighborhoods earn less revenue than similarly rated businesses elsewhere. Conventional retail establishments underserve majority-Black neighborhoods—even Black neighborhoods with high household incomes—hurting the market attractiveness of those neighborhoods and forcing leakage in consumer spending. This is all evidence of the severe cost of persistent segregation and discrimination in the real estate market. Devaluation has pernicious impacts on Black household wealth, dampening these families’ potential to launch businesses or pay for college.

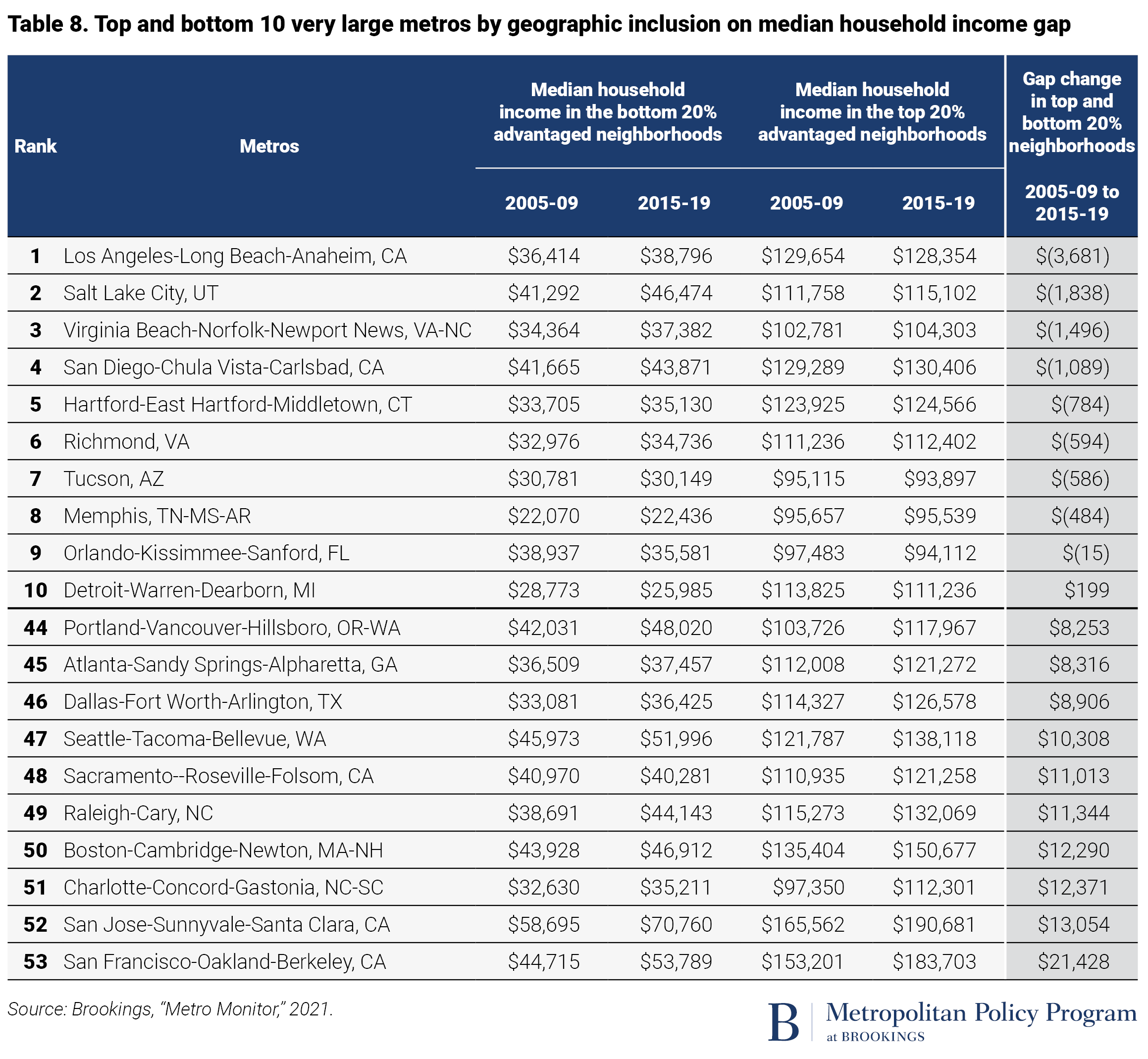

One proxy for progress is closing the income gap between the most advantaged and disadvantaged neighborhoods in a metro area through private investment, product development, and corporate philanthropy. Such data is available through Brookings’s Metro Monitor 2021, which provides metro-level data on geographic inclusion between 2009 and 2019. Among the 53 metro areas where the population exceeds 1 million, only nine have narrowed the median household income gap between the most advantaged and disadvantaged neighborhoods over the decade-long time period. Los Angeles, Salt Lake City, and Virginia Beach, Va. stand as the best-performing regions (Table 8). But even among the nine high-performing metro areas, the income gap by neighborhood narrowed in some cases (such as in Detroit and Orlando, Fla.) because median household incomes in both sets of neighborhoods shrank in the last 10 years—a troubling trend overall.

In the remaining 44 metro areas with populations over 1 million, the household income gap expanded. In most cases, this was due to wealthier neighborhoods getting wealthier, with household incomes in these neighborhoods growing at a faster rate than those in struggling neighborhoods. Workers and families in lagging neighborhoods simply do not have the same access to opportunities or market investments that can propel their communities forward. Such investments would improve outcomes for people of color, considering that Black, Latino or Hispanic, and Native American people who live in poverty are more likely to live in low-income or working-poor neighborhoods than white people in poverty.

These sample regional indicators can inform goal setting and benchmarking in specific strategies related to workforce, business growth, and neighborhood wealth creation. These can supplement regional leaders’ broader efforts to track overall regional performance in inclusive economic growth. Tools such as Brookings’s Metro Monitor offer inclusive economic indicators to help local leaders track their regions’ performance on matters such as the racial and geographic earnings gap.

Some leaders are looking beyond traditional indicators and producing their own dashboards to measure economic competitiveness and inclusion. These include the KC Rising metrics in Kansas City, Mo. and the MSP Regional Indicators Dashboard in Minneapolis-St. Paul, hosted by the Greater MSP Partnership, the Center for Economic Inclusion, and several other nearby entities.

Emerging models: Private sector actions to watch in metro areas

This paper has laid out a three-part action framework for regional CEOs to advance racial equity and an equitable economy, including a set of proposed KPIs for CEO coalitions and their partners to hold each other accountable. In each of these three actions, there are promising efforts underway, some of which are highlighted below.

CEOs driving internal company actions on diversity, equity, and inclusion

Indianapolis-based financial services firm OneAmerica offers a good example of how a major firm can make a difference in its home region. In 2018, OneAmerica’s CEO announced an initiative to raise wages for their lowest-paid workers to $18 per hour while also working to make promotion ladders more accessible. This came in response to a Brookings report that found that only 26% of jobs in Central Indiana were good or promising—meaning too few jobs were paying a family-sustaining wage, providing health care benefits, or offering full-time work for a worker without a college degree.

Root Insurance is a homegrown firm headquartered in Columbus, Ohio that made a critical change in its consumer-facing services to eliminate systemic bias. Founded in 2015 to disrupt the car insurance industry, Root offers rates based primarily on driving behaviors instead of demographics. Last August, the company’s CEO announced it would eliminate the use of credit scores in its pricing model, removing the inherit bias that comes with those scores, which disproportionately penalize some groups due to lack of access to fair lending and have no bearing on driving quality. Root said it changed its core product and service to “fight bias and systemic inequality in auto insurance” and better serve its customers.

CEOs acting collectively to make regionwide progress on racial equity and equitable growth

Since the summer of 2020, CEOs in several regions and states have joined forces to advance racial equity in their economy. In Central Indiana, Business Equity for Indy is improving opportunities for Black talent, businesses, and communities. In Chicago, the Corporate Coalition is aiming to reduce inequality—especially by neighborhood—through changes in business practices and investments. The Minnesota Business Coalition for Racial Equity is tackling systemic racism and improving opportunities for Black Minnesotans. And Washington Employers for Racial Equity has united over 70 major employers across the state—including Microsoft and Starbucks—to advance racial equity in the corporate sector, including increasing Black representation in management roles and supply chains.

While these and other efforts are still nascent, a few regional CEO efforts are worth noting for their collective actions so far on diversity hiring, procurement, and neighborhood wealth creation.

First, on hiring diverse talent in growing occupations, a number of Chicago companies came together to form the Chicago Apprenticeship Network, with a goal to provide and foster 1,000 apprenticeship opportunities in occupations such as accounting, software development, data analytics, and human resources. The program recruits talent from every ZIP code in the region, with many representing underserved populations. The program’s early success would not have been possible without CEO commitment and leadership, as well as their collaboration with community colleges, nonprofits, and government.

On procurement, 10 CEOs in Birmingham, Ala. joined the mayor in a commitment to supplier diversity. These leaders were already concerned about the low number of Black-owned businesses in a region where Black residents make up 28% of the population, but racial injustices during the summer of 2020 prompted the business community to act. The group launched a program called VITAL—Valuing Inclusion To Accelerate Lift—that includes a private sector commitment to collect and make transparent their procurement data as a first step in awareness, tracking, and reforms in vendor relationships. A coalition of major CEOs in New Jersey (including BD, Campbell Soup Company, Johnson & Johnson, and Prudential Financial) went further by committing to increase their procurement spend with N.J.-based small and minority-owned suppliers by 25% by 2025.

In Chicago, the Corporate Coalition is a good example of what CEOs and partners can do together to reduce severe place-based economic inequalities. To directly invest in employment and wealth creation, executives from lead companies such as AT&T, Comcast, Hyatt, and Wintrust are working together to provide trauma-informed and healing supports for employees from neighborhoods that have experienced trauma, helping employees advance in their careers while at the same time improving overall company performance. Other members are supporting catalytic real estate projects in the south and west sides of Chicago; this includes providing business opportunities such as tenancy or vendor partnerships and providing technical supports to project sponsors, many of whom are led by people of color. The Coalition is also developing a new fund that will harness the collective commitment of the corporate sector to fill persistent capital gaps, extending the reach of the existing community development financing ecosystem in innovative ways that advance catalytic real estate projects.

A network of financial institutions and real estate developers in a region can pursue place-based racial equity by creating more financial tools and private capital outside of philanthropy for Black and Latino or Hispanic residents to build wealth in community assets. With the partnership of banks that offered long-term real estate loans and a letter of credit, the Community Investment Trust in Portland, Ore. has been able to successfully pilot an inclusive, risk-free investment model designed for local residents in a working-class neighborhood to share ownership of a retail development that houses several minority-owned businesses. The model enables residents to gain financial dividends from the development’s increase in market value. The banks also worked with the Community Investment Trust to design a six-hour financial literacy course required for all investors. The trust is increasing the wealth of East Portland residents, and with the investors’ personal stake in the properties, they also become loyal and frequent customers of the small businesses, creating mutual benefit for everyone.

CEOs influencing business-led civic organizations to embrace racial equity and equitable growth

Finally, CEOs can support staff of civic entities, business groups, or other private-public partnerships for which they serve as chairs or board members in these organization’s journey toward greater racial equity and more equitable economic growth. A few groups are making critical shifts in their goals, partnerships, and programming.

For example, Portland Means Progress is a collaboration among regional economic development entities, the city, and workforce intermediaries that is executing initiatives to address three goals: 1) strengthen the racially diverse, homegrown workforce; 2) support small businesses owned by people of color; and 3) create a more inclusive workforce culture by providing DEI training for local workplaces.

In Indianapolis, the Indy Chamber has adopted an inclusive economic growth strategy in which DEI values are embedded across their economic development programs. For instance, they worked with the mayor’s office to launch an inclusive incentives program that rewards local firms that create jobs paying at least $18 per hour with benefits, and invests in programs that remove barriers for local workers to access good jobs, such as child care and transportation. Indy Chamber also has a partnership with the Department of Corrections to help returning citizens launch new businesses. In addition, during the pandemic, they have been serving as a community development financial institution (CDFI) to help small businesses that traditional banks overlook through loans and technical services. These businesses are most often microbusinesses (businesses with fewer than 10 employees), nonemployer businesses, and Black- and Latino- or Hispanic-owned businesses.

CEOs can support the formation of and participate in efforts like minority business accelerators to strengthen cohorts of new and existing high-growth Black- and Latino- or Hispanic-owned firms by offering resources like mentorship, access to capital, and business networks. The Cincinnati Chamber in Ohio is a good illustration of this; it has formed a Minority Business Accelerator to help scale high-growth businesses owned by minority entrepreneurs. With a goal of doubling the annual aggregate sales of its 35 portfolio firms to $2 billion and creating an additional 3,500 jobs in five years, some of the resources the accelerator offers include business assessments, capacity-building, procurement opportunities, networking opportunities, and assistance with strategic planning, equity financing, business acquisitions, talent attraction, and more.

CenterState CEO, the local business leadership organization in central New York, is taking steps toward deepening racial equity in its work by forming a new Racial Equity and Social Impact portfolio. Its new vice president for racial equity and social impact is leading the prioritization of race and equity work within the organization and community. This includes developing and delivering new DEI services for the region’s businesses, as well as leading staff trainings and developing accountability metrics to advance CenterState CEO’s diversity, equity, and inclusion goals.

Conclusion

A region’s business community can be a powerful force. As employers, investors, and agenda setters, they shape the economic fortunes of workers and their home regions.

Business leaders can use that power to make needed company changes and collaborate to include more people, businesses, and neighborhoods in regional economic success. To start, that means reversing the structural exclusion that Black and Latino or Hispanic workers and owners face in cities and the broader economy.

This is not an act of charity. Adopting diversity, equity, and inclusion as a competitive asset is good for growth. It inspires and retains the next generation of talent who expect a DEI culture in their workplace. And when done together, racial and economic justice leads to greater community trust, economic dynamism, and wealth creation.

We hope this report provides a useful framework for private sector leaders who want to be at the vanguard of a racially equitable economy. As we demonstrate, regional performance metrics and promising models exist to help the business sector move from commitments to action. These actions are long overdue. The soul of the nation is at stake.