HEALTH

In Spring 2020, COVID-19 changed the world. Within a matter of weeks, hundreds of thousands of lives had been lost. The economies of most major countries were stalled. In normal times, health is a slow-burning issue. As individuals, many of us will have an acute health crisis, but these take place at different times, spread out across the population. But COVID-19 has been a shock to the whole system. In the U.S., the pandemic has also highlighted the poor health of many of our citizens, rendering them more vulnerable to the virus, as well as revealing deep divides by race, geography, and class. It has served as a sharp reminder that our health cannot be separated from the rest of our lives.

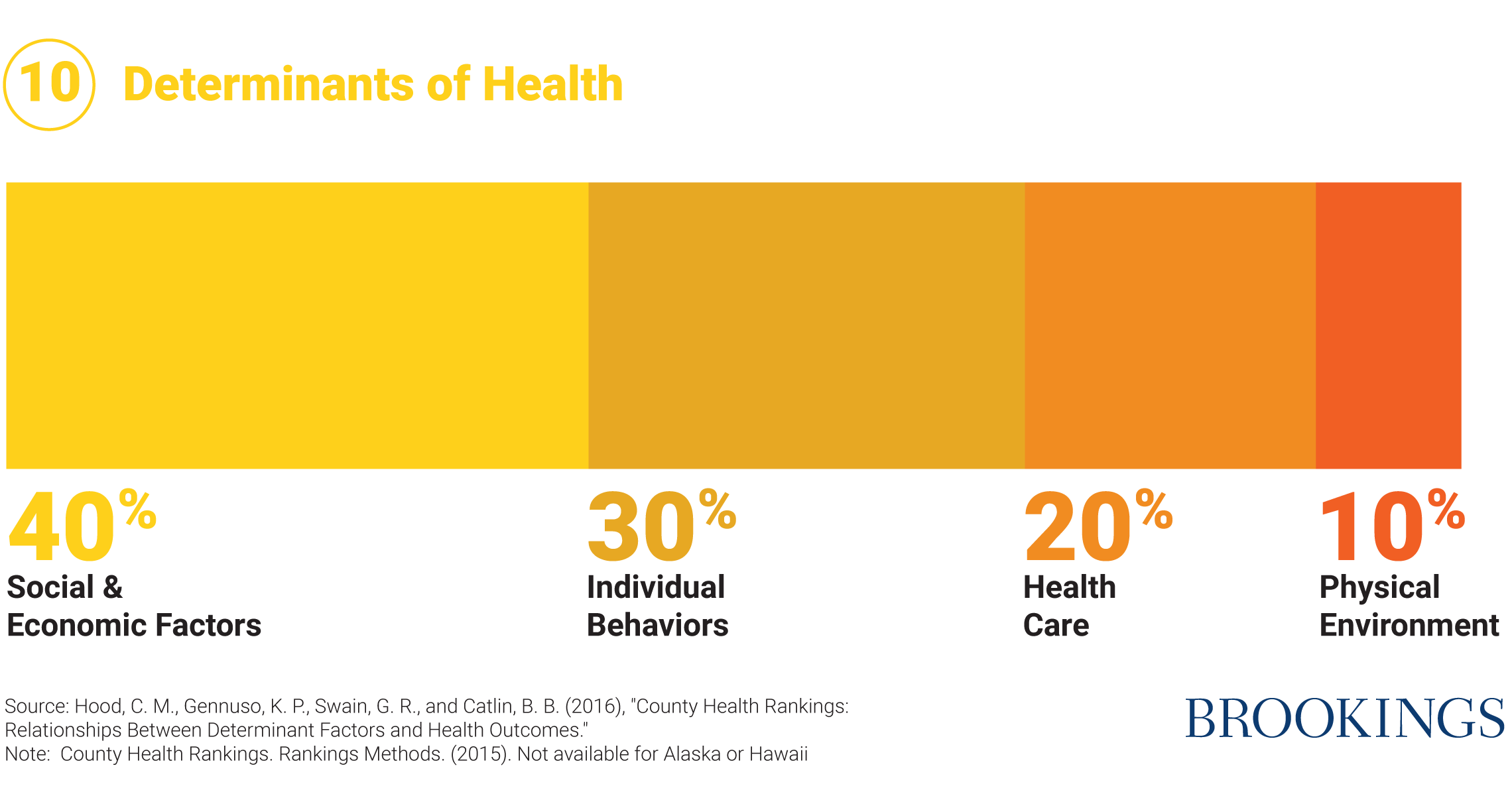

It is common, including in policy circles, to treat health and health care almost as synonyms. It hardly needs saying that the U.S. health care system is in urgent need of reform, especially in order to bring down costs. But in the heated debates about health care it is too often forgotten that the state of our health is intimately connected to our economic resources and opportunities, the structural inequalities we face, the relationships we form, and the respect we are paid. In fact, social, individual and economic factors impact health three times as much as health care does (Figure 10). In that sense, every page of this contract is about health; but in this chapter we address the challenge more directly.

Health matters

Few of us doubt the importance of our health, so it is little surprise that Americans report much higher levels of overall life satisfaction and greater optimism when they consider themselves to be in good health. Life just goes better with a healthy body and mind. Importantly, there is a particularly strong connection (in both directions) between self-assessed wellbeing and chronic ill health. As well as being valuable in its own right, good health facilitates learning, employment, and social relationships. In this sense health is another form of “human capital;” investing in good health pays off in other areas of life too.

Unhealthy, before COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic hit the U.S. harder than most other nations for many reasons, not least because of the vacillating and inconsistent response of the Trump Administration, an absence of preparedness, and a weak public health infrastructure. But the pandemic has also served to highlight the general state of America’s health when the virus hit our shores – especially in terms of pre-existing conditions, or “co-morbidities” that are associated with poorer outcomes.

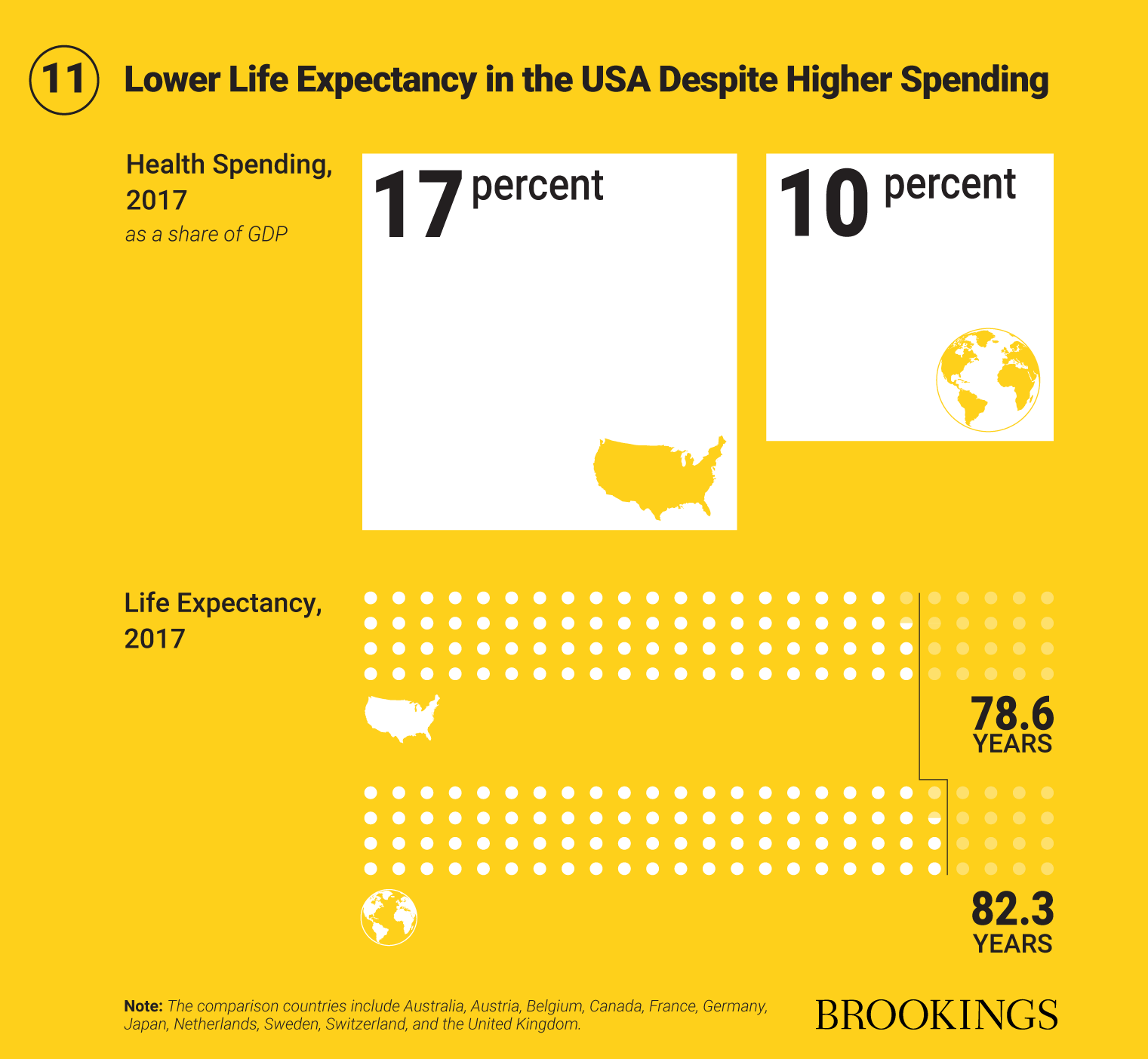

Comprehensive studies conducted by large teams of NIH experts show that the U.S. lags other wealthy nations, especially in terms of chronic disability and morbidity. Diet-related risks now account for more deaths than any other factor. The U.S. has dropped from 18th to 27th place among 34 OECD nations on the key aggregate metric of age-standardized death rate. A good yardstick of overall progress in terms of health is life expectancy, which has risen considerably in recent decades in most countries in the world. But the U.S. has seen slower increases than comparable countries (Figure 11). Perhaps most worrying, life expectancy in the U.S. is now trending downwards, a break with both the historical trend and with other countries.

The poor health of the U.S., by comparison to other similar nations, is even more striking given health care spending. Seventeen percent of U.S. GDP went towards health care in 2017, compared to an average of 10 percent in comparable nations. This illustrates not only the cost and inefficiency of the U.S. health care system, but also the important distinction between health and health care.

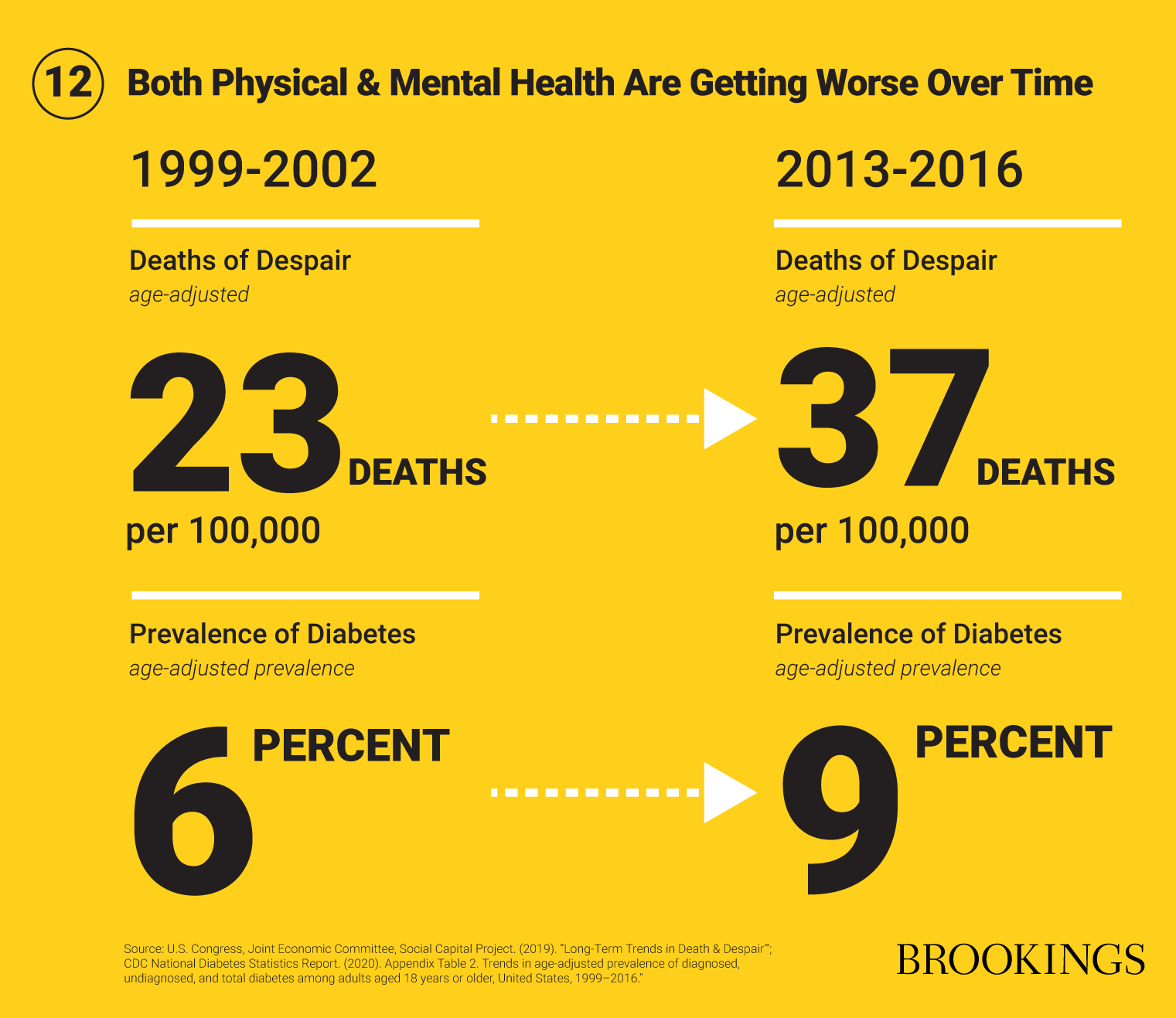

The worsening position of the U.S. in terms of life expectancy is largely the result of rising death rates among adults between the age of 25 and 64. There has been a sharp increase in “deaths of despair,” especially related to drug overdoses, alcohol-related diseases, and suicide. Since the turn of the century, deaths caused by drug overdoses, for example, rose over three-fold (from 6.1 deaths/100,000 to 21.7 deaths/100,000).

Mental health trends in the U.S. are deeply troubling. Suicide rates are at their highest level in half a century, with sharp rises among middle-aged whites in particular. Mental health conditions now account for 35 percent of claims for Supplemental Security Income or Disability Insurance. Americans facing economic insecurity, and/or racial discrimination are at particularly high risk. Poverty and racism are risk factors in terms of mental health – another reminder that social and political determinants of health matter.

Our physical health is worsening on many fronts, too. Two in five Americans are now obese, and obesity is associated with many chronic health conditions, including, according to the CDC, “diabetes, hypertension, high cholesterol, cardiovascular disease, stroke, arthritis, and certain cancers.” One in ten Americans already have diabetes. That number could rise to 1 in 3 by 2050 if current trends continue.

These health issues are not unique to those at the bottom of the income distribution – they impact the middle class as well. Obesity rates among adults, for example, are similar for people in households at all income levels up to around the $100,000 mark. Childhood obesity rates are falling in well-educated and more affluent households, but continuing to rise for others. There are also worrying signs of a stronger link in health status between parents and their children.

In short, the big problem we face is a rise in chronic health problems – both physical and mental – among very large swaths of the population which are corrosive to the quality of life of the American middle class. The treatment of chronic disease, impacting 60 percent of the population, now accounts for at least two-thirds of health care spending. Our hope is that the 2020 pandemic acts as an alarm call to address these deeper health concerns.

Broken systems, bad policy

The policy debate about health in the U.S. is unbalanced in three major ways:

- Health often takes second place to health care, even though health is influenced far more by social factors than medical ones. It is clear that what scholars label “social determinants” of health – economic resources and opportunities, education and skills, communities and neighborhoods and housing and the built environment – deeply influence health.

- Mental health is treated separately – and less effectively – than physical health. This is despite the fact that mental health conditions afflict around one in five adults, and account for a significant proportion of the “disease burden” in the U.S. State of mind often matters as much as the state of our bodies.

- Chronic health conditions are often neglected by comparison to acute health problems, which are often more salient and take the form of an emergency or crisis. But in terms of quality of life, both acute and long-term health problems are damaging.

These are systemic problems, requiring systemic solutions. It is often cheaper, and always better, to prevent ill-health through social spending than to treat it medically later. A radical rebalancing of government spending is needed, from health care to social support, especially to known “upstream” factors impacting health, such as housing, poverty, and education. Likewise, a reinvention of mental health care, and full integration into the health care system as a whole, is needed. Last but not least, the rise in diet-driven chronic disease calls for nothing less than fixing our entire, broken food system – from agricultural subsidies (especially for high-fructose corn syrup), official dietary guidelines, advertising, school lunches, and budget choices. As Tufts nutritionist Dariush Mozaffarian bluntly puts it, “Currently, junk foods are effectively subsidized by billions of dollars of health care spending, while the true economic value of nutritious foods is not fully recognized.”

There are, then, many policy changes that are needed. Here we highlight two in particular, each of which should be seen as illustrative of the kind of reforms that would result from a genuine, system-wide effort to improve America’s health:

- Universal access to effective therapy without cost

- A national tax on sugar-sweetened drinks

Therapy for all

In 1953, a new bell was rung. Forged in metal from chains used to restrain people suffering from mental illness, the inscription on the Mental Health Bell reads:

Cast from shackles which bound them, this bell shall ring out hope for the mentally ill and victory over mental illness.

Seven decades later, huge progress has been made in the treatment of mental illness – and in the treatment of those who suffer. But they still carry a social stigma, even among those who should know better. To put this in personal terms, it is much more likely that either of the two of us will tell you about our own or our families’ broken bones than about struggles with depression and anxiety. Creating a culture where mental illness is recognized and not stigmatized is a task for all of us, in all our relationships.

But there are some much-needed changes on the policy front, too, especially in terms of screening, mental health parity with physical health, and provision of quality therapy to all.

Mental health problems typically present early in life; three quarters of lifetime mental health conditions begin by the age of 24. But an average of 11 years elapses between the onset of symptoms and diagnosis. Early detection allows for early and more effective treatment. Screening for depression and substance use disorder has received the necessary, and legally binding, approval from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force and is formally covered under Medicaid and the Affordable Care Act. But too often it is not provided. Mental health screenings ought now to be universal in schools and colleges, as well as in all clinical settings, including those serving pregnant women and new mothers.

Laws are in place to enforce parity between mental and physical health care, but the necessary practices are often lacking – in part because the legal framework has significant gaps. A good place to start would be the implementation of the recommendations of the Mental Health and Substance Use Disorder Parity Task Force in 2016, especially leveling the field in terms of pre-authorization requirements, introducing parity “templates” for insurance companies, and allowing civil financial penalties for parity violations. All employer plans should also be legally required to cover mental health conditions.

I want to talk about mental health… the mind and body are one.

Retired Nurse, Wichita, KS

A simple, single step towards better mental health would be the provision of universal, effective therapy. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) provides an obvious example. CBT is a “problem-focused, empirically based psychotherapy that teaches patients to detect and modify thought patterns and change behavior to reduce distress and promote well-being.” It has been proven to be highly effective and relatively inexpensive. This means that overall, the benefits of universal provision of CBT will outweigh the costs, by preventing later worsening of mental health conditions (saving bigger medical bills), supporting employment (and therefore increasing tax revenues), and reducing disability claims (and therefore reducing benefit spending). That is why the U.K. has introduced free access to therapy, without referral, through its National Health Service. It is also why the U.S. Army is providing psychological support to soldiers to promote “mental fitness.” As Brigadier General Rhonda Cornum, director of the Comprehensive Soldier Fitness program, put it, “We need to attend to psychological fitness the same way we do physical performance.” This is true for everybody. Universal coverage would also send a signal that mental health problems of one kind or another are the norm rather than the exception, potentially helping to reduce stigma.

In the U.S., providing universal free access to therapy will be more complicated than in the U.K. but is still achievable through improvements such as:

- Providing universal access to CBT in all public schools and colleges, as well as for those performing civilian or military service.

- Ensuring that Medicare, Medicaid and the Affordable Care Act (as well as a new public option) provide for first-dollar coverage of CBT for all.

- Making permanent more flexible rules on teletherapy introduced during the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Increasing supply of providers: the U.S. needs thousands of extra psychologists and licensed therapists.

- Expanding Community Health Centers, who can provide high-quality mental health support in a primary care setting, especially to traditionally under-served groups.

CBT is relatively cheap, it works, and saves money in the long run. Most importantly, it improves quality of life. Of course, there are other forms of therapy that are equally if not more effective for some conditions – Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT) for substance abuse disorders, for instance – which should also be available to all at no cost. We have argued here in particular for CBT because of the strong evidence for broad effectiveness and low cost. But it should be seen as an example of the kind of reforms necessary to elevate mental health care more broadly.

Tax sugary drinks

There are many reasons why the physical health of our nation is deteriorating. But two stand out: diet and nutrition. We are eating and drinking our way to diabetes, heart disease and, all too often, an early grave. Over the long term, nothing could improve Americans’ physical health more than improving diet and nutrition – and especially, reducing sugar consumption.

Many would argue that what individuals choose to put into their own bodies is a matter of personal choice. As good liberals (in the proper sense of the term), we agree. But that does not mean public policy has no role to play in encouraging healthier choices, not least by using taxes to raise (or lower) prices. Few now object to the idea of taxes on alcohol or tobacco, for instance – and they work, in terms of moderating consumption.

The political argument is made more complex by the steep class gradient and wide race gaps in the consumption of sugary drinks and snacks, and in rates of certain chronic conditions such as diabetes, obesity, and heart conditions. In Ward 8 of Washington DC, the poorest in the city and predominantly Black, the rate of Type 2 diabetes is 15 percent; in Ward 3, the richest and whitest, the rate is 2 percent.

I’ve got to keep my health… so I can make sure I’m there for my son.

Young Mother, Wichita, KS

Even citing these shocking statistics can provoke a fear that we are about to start “blaming the victim,” rather than the structural conditions influencing health more broadly. But the opposite is true. The blame here lies not with individuals. It lies with a broken food system. The scarcity of affordable nutritious food for many families, a lack of time to prepare meals, the predatory marketing of corporations – these are all structural barriers to better health.

The evidence for the impact of sugary foods and drinks on health is now clear. For every one to two daily servings of soda consumed, the lifetime risk of developing diabetes increases by 30 percent. A third of the added sugar in the American diet (for children and adults) comes in the form of sugar-sweetened beverages. Sugar-sweetened beverages contribute directly to unhealthy weight gain.

Many cities have introduced a tax on soda; some, like Chicago, have then repealed them. One problem is that consumers very often simply drive to the neighboring county. Soda sales in the city of Philadelphia fell by 51 percent after the introduction of a 1.5 cents per ounce tax – but sales in nearby areas increased by 43 percent.

The solution is to follow Mexico’s lead and enact a national tax on sweetened drinks, at a rate high enough to deliver real health benefits. Previous legislative efforts led by Congresswoman Rosa DeLauro have failed. “It’s an idea that we should be exploring,” said Barack Obama in 2009, before quickly shelving the idea. But COVID-19 has turned a harsh light on the implications of poor metabolic health for quality of life, and for the risk of death. There is a case in theory for a graduated tax on damaging ingredients, especially sugar and starch in all processed foods and drinks. But in practice, it is easier to tax the main delivery mechanism (in the U.S.): sweetened beverages. In terms of design, the best approach is to tax sugar and corn syrup content, rather than just the volume of the drink itself. A tiered tax, with the highest rate (2 cents an ounce), levied on drinks with the highest sugar content (20 grams per 8-ounce serving), as proposed by the American Heart Association, would be especially effective.

Over a lifetime, on reasonable assumptions, this tax would save half a million lives and cut health care costs by $100 billion. A tax of this kind would also raise around $5 billion a year, according to the Congressional Budget Office. This additional revenue should be earmarked for preventive measures proven to reduce health disparities.

Such a tax looks initially “regressive” in pure economic terms, since lower-income families spend more on sugary drinks. But considering welfare more broadly it is either neutral or slightly progressive, since the biggest health benefits are also experienced among the less affluent. The health benefits also differ by race. The tax would reduce cardiovascular disease rates (per million) for Black and Hispanic Americans by 15,000, compared to 9,000 for whites.

As a nation we should also adopt Boston’s approach to school meals, making them free to all students regardless of income, and cooking real food in actual kitchens, rather than reheating processed food shipped by food conglomerates. This could dramatically improve health outcomes. We also need better research on the impact of nutrition on chronic health conditions: a good start would be the establishment of a National Institute of Nutrition at the National Institutes of Health.

A health reset

It hardly needs to be said that much more than these two headline measures – big though they are – is needed to improve the health, and therefore quality of life, of the American middle class. We also support, for example, universal access to reproductive health care (see Chapter 3); universal rights to time off work with pay (see Chapter 2); expansion of subsidies for individuals buying health insurance; stronger action to tackle the opioid epidemic; bearing down on health care costs; and automatic enrollment into a health plan, as our colleague Christen Linke Young has proposed.

Above all, and as we have argued throughout this contract, policy needs to shift in the direction of prevention rather than cure. Too many of our citizens have suffered or died in the COVID-19 pandemic, especially Black Americans, who as Dayna Bowen Matthew, Dean of the Law school at George Washington University puts it, already “live sicker and die quicker.” A strong middle class is one that is healthy both in mind and body. In 2020, America’s failings on this front are more vivid than ever. It’s time for a reset.

Special thanks to Tiffany Ford and Ariel Gelrud Shiro for their research support.

America can only be as strong as the American middle class. We believe that the new contract we have described here, based on the core principles of partnership, prevention, and pluralism, holds out the promise of a better future for the middle class — and therefore for the nation. Let us know what you think.