Content from the Brookings Institution India Center is now archived. After seven years of an impactful partnership, as of September 11, 2020, Brookings India is now the Centre for Social and Economic Progress, an independent public policy institution based in India.

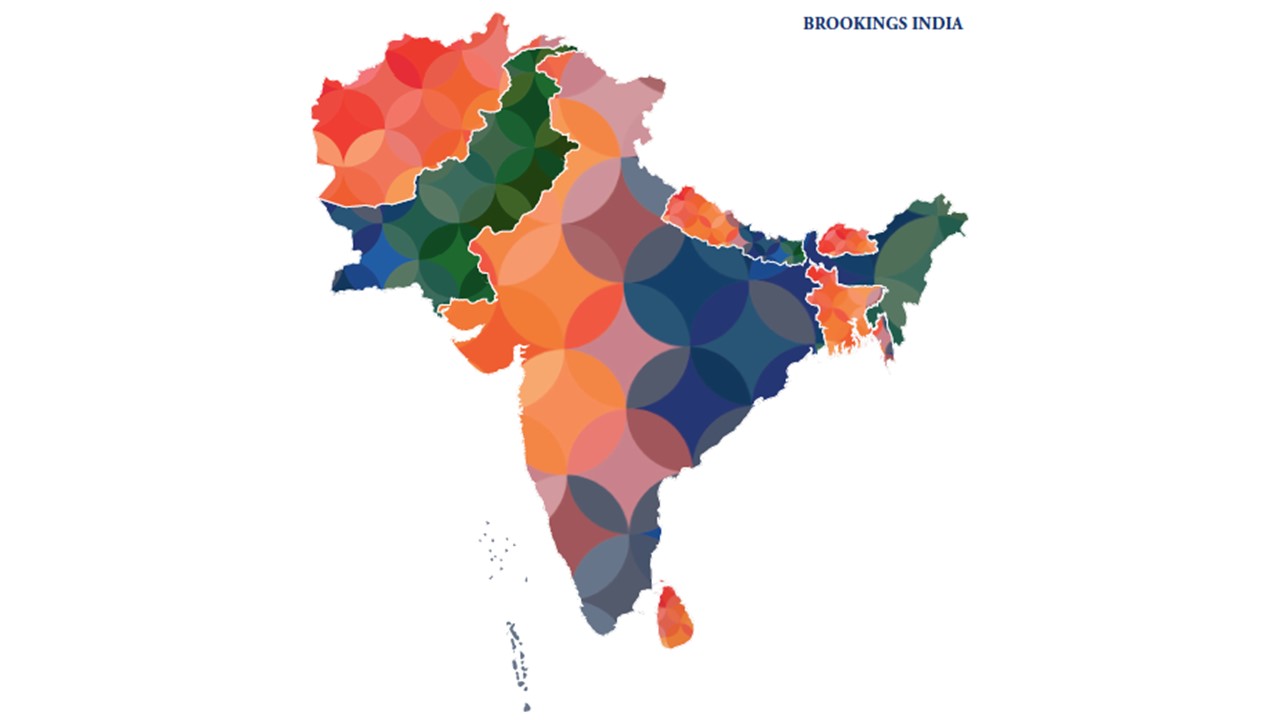

Education is a powerful medium to unleash the potential of the SAARC region by cutting poverty and promoting development. It can also be an instrument of soft power for a nation like India by raising its cultural and political, especially democratic, attractiveness for others. With rapid globalization and expanding communication technology, India can enhance its position in the SAARC neighbourhood through higher education. It can do so by attracting greater number of international students from this region as well as developing cultural exchange programs. This helps to build a better understanding and cross fertilization of ideas through greater interaction among students, scholars and academics in the SAARC countries, and could contribute to a SAARC community.

Government policies can either enhance or diminish a country’s soft power. Within a liberal democratic setting, Indian universities can attract a large number of students and potential future leaders of the SAARC region. Such links and networks can be of tremendous value for India. For example, India’s foreign policy vis-à-vis Myanmar was greatly shaped by its relationship with its democratic leader Aung San Suu Kyi who lived in India and was educated at Delhi University.

The data from 2012 indicates that more than one third of all foreign students who study in India, are from the SAARC countries. This is likely to be an underestimate of the true number because it only includes full time degree programs. Despite its own acute shortage, India has emerged as a regional leader in the higher education space due to its comparative advantage vis-à-vis the other SAARC countries. It must recognize this opportunity and promote investments into opening new institutions, improving teacher quality, raising research output, and creating an efficient regulatory environment to unleash the potential of the higher education sector in India.

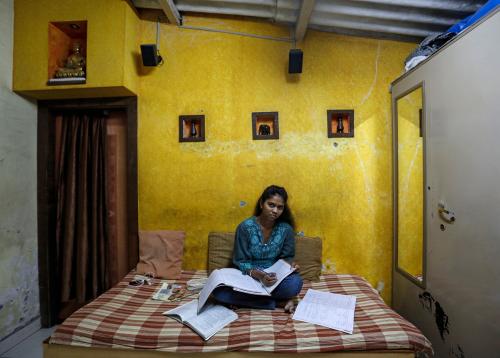

India itself faces acute shortage of access to higher education facilities. Over the past few decades, it has made very small progress in improving its gross enrolment ratio in higher education. This measures the number of individuals going to college as percentage of college-age population. China’s gross enrolment ratio was 8 percent in 2000 which impressively grew to 23 percent within a decade, by 2008. India, meanwhile, rose from 8 percent in 2000 to a meagre 13 percent in 2008. China brought about this growth in access through massive investments in higher education and research and has since emerged as Asia’s leader in this sector. There is significant interest amongst the high quality international faculty pool in relocating to Chinese universities given their attractive compensation and research environment.

The creation of the South Asian University in Delhi in 2010, by the member countries of SAARC is a significant step towards promoting regional development in the area of higher education. The university attracts students from all member nations and its degrees are recognized by all eight SAARC countries. Tuitions will be heavily subsidized and compensation packages have been designed to attract high quality faculty. Though significant, this development is just a beginning and must be further reinforced by promoting investments outside of government institutions to attract the best minds amongst scholars of South Asia. For this regulatory hurdles have to be eased to facilitate private and foreign universities to function in India. It must also be closely followed by a friendly visa regime for international students and faculty in India. Presently in addition to the visa, there are several additional registrations required including visits to nearby police stations which create significant bottlenecks.

With less restrictive visa policies, India will see a surge in the applications from foreign students wanting to study in India. The long term implications for India is that it will earn an opportunity to influence, and learn from foreign students and scholars from the neighbourhood. This will raise India’s awareness and understanding of cultural differences, which is necessary for designing policies pertaining to the SAARC countries. This will also make Indian society less parochial and more sensitive to differences which is required to strengthen regional cooperation in a fast globalizing world.

Within the South Asian neighbourhood, India faces several security concerns and spends significant resources to meet these threats. India’s long term success in this context will critically depend upon developing a deeper understanding of its own soft power, which lies in its liberal cultural heritage and pluralistic democracy. India must invest in promoting this through its higher education sector by attracting talent from the neighbourhood and thereby nurturing future ambassadors for its shared values.

_______________________________________________________________________________

This chapter is a part of Brookings India’s briefing book, “Reinvigorating SAARC: India’s Opportunities and Challenges.” To view the preface and table of contents, click here.

***

Shamika Ravi is a fellow with Brookings India in New Delhi and the Brookings Institution. She is also Visiting Associate Professor of Economics, Ashoka University and Research Affiliate, Financial Access Initiative, NYU. Her research is in the area of development economics with a focus on gender inequality and democracy, and financial inclusion, and health.

_______________________________________________________________________________

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).