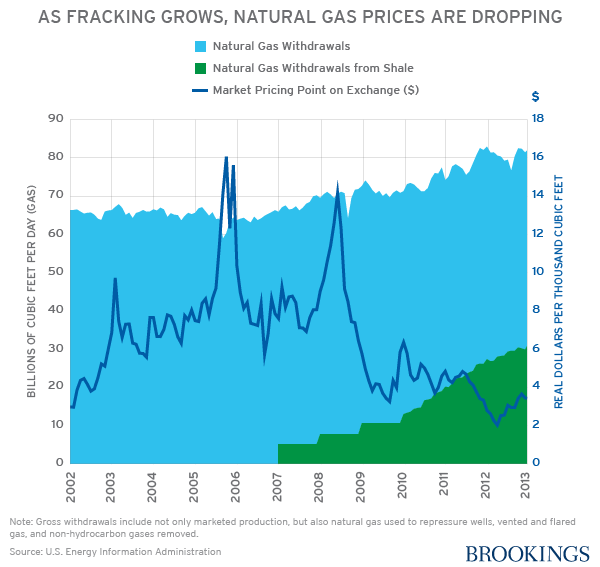

The recent shale gas boom (“fracking”) in the United States has been beneficial to the economy, dropping natural gas prices 47 percent compared to what the price would have been prior to the fracking revolution in 2013, and has improved the economic well-being of consumers $74 billion per year. The authors estimate residential consumer gas bills have dropped $13 billion per year from 2007-2013 thanks to the fracking revolution, amounting to $200 per year for gas-consuming households.

In the first estimates of the economic welfare and distributional impacts of the U.S. shale boom, Catherine Hausman of the Ford School of Public Policy at the University of Michigan and Ryan Kellogg of the Department of Economics at the University of Michigan and the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) find that the expansion of the natural gas supply has reduced gas prices by $3.45 per 1000 cubic feet, and that the wholesale price reduction has been fully passed on to retail natural gas prices.

All types of energy consumers gained from the boom, they find: residential customers at $17 billion per year; commercial at $11 billion; industrial customers at $22 billion; and electric power customers at $25 billion – for a total of $74 billion.

However, natural gas producers have experienced a reduction in surplus because their gain from the expansion of supply has been outweighed by the fall in gas prices, which is likely to hit areas hardest that have historically produced large quantities of conventional natural gas but have not developed shale resources.

Overall, the authors find that 2013 producer surplus is lower than what it would have been before the boom by $26 billion per year. But given the consumer gain of $74 billion, the net overall gain is $48 billion.

Looking specifically at regional effects, one would expect colder states that use natural gas for space heating to be the area to benefit most from shale gas. Yet the authors find that the area to reap the most gain is West South Central (Arkansas, Louisiana, Oklahoma and Texas) at $432 per person in consumer benefits, followed by East North Central (Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Ohio, and Wisconsin) with $259 per person in benefits. The area to gain the least is the Pacific (California, Oregon and Washington), but consumers there still benefited to the tune of $181 per year.

Because natural gas is an important direct input in chemical and cement manufacturing, and is also an indirect input to essentially all manufacturing via its use in electricity generation, Hausman and Kellogg examine the shale gas impact on manufacturing overall – an industry which has been in decline in the US for decades. While they note it is difficult to pinpoint a precise causal effect, they find that gas-intensive manufacturing has indeed experienced an expansion of activity as a result of the shale boom, with the most pronounced effect in fertilizer manufacturing – the most gas-intensive sector of all.

Finally, the authors review fracking’s environmental impacts and discuss the difficulty facing regulators, noting that while scientists remain concerned about a number of environmental damages caused by fracking, the data collection has not kept pace with the boom in extraction, and a great deal of uncertainty remains regarding pollution from fracking. “This has limited the ability of regulators to target those areas of greatest concern; it has also limited their ability to regulate in a cost-effective way. Higher quality, comprehensive data on baseline levels of environmental quality as well as on emissions from individual producers would go a long way. In the absence of such data, regulatory options remain limited and are unlikely to be cost effective,” they write.

Hausman and Kellogg conclude by raising an issue currently facing policymakers: whether to permit large-scale overseas export of liquefied natural gas (LNG). Expanding natural gas exports will drive up U.S. gas prices, thus reducing consumer surplus but increasing producer surplus, with the gain accruing to producers will outweigh the losses suffered by consumers, they conclude.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).