During the first couple months of the COVID-19 recession, an estimated 22 million Americans – roughly 13 percent on the U.S. workforce – experienced a job loss. The initial impact on employment was largest for Black, Latino, female and less-educated workers. While the U.S. economy has quickly regained many of the jobs that were initially lost, some of those workers have been displaced from jobs and employers with which they had significant experience, and the negative effects of such displacements can be large and persistent.

In our new report, we use data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) to understand the earnings effects of job displacements that have occurred over the last 30 years in the United States. We consider a worker to be displaced if they involuntarily lose a full-time job that they held for at least two years. Using an event study fixed effects model, we compare the earnings of displaced and non-displaced workers for the five years leading up to a displacement and the ten years following it.

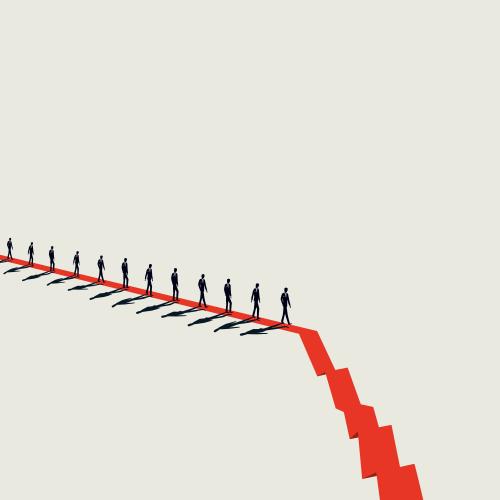

A steep and lasting negative shock

Figure 1 shows the effects of a job displacement on log annual earnings for each year relative to the displacement. There are several key takeaways from the figure. First, there is a large initial negative effect of a displacement on earnings. We estimate a 57 percent decline in annual earnings in the year immediately following displacement, which is in line with earlier displacement studies. Second, although earnings rebound to some extent in subsequent years, the negative effect lingers. Even ten years after a displacement, workers earn about 25 percent less compared to their non-displaced peers.[1] Simply put, Figure 1 has a stark message: workers who experience a job displacement suffer immediate and large earnings losses, which persist even a decade later.

What is behind the large earnings losses? Wages vs. hours worked

To understand the mechanism behind the lasting negative earnings effect of displacements, we look at the impact of displacements on hourly wages and annual hours worked. While we find that workers work significantly fewer hours in the first couple of years following a job displacement, the longer-term impact is driven by a decline in hourly wages. Figure 2 plots the effect of a job displacement on log hourly wages by relative year.

Immediately after a displacement, hourly wages decline by almost 15 percent and they never fully recover. Ten years after a displacement, workers still experience a nearly 15 percent decrease in hourly wages relative to their non-displaced peers. This suggests that the lingering effect of a job displacement on annual earnings is driven by a decline in wages and not by a decline in the likelihood of being employed or in hours worked.

Protect workers with Unemployment Insurance and Earned Income Tax Credits

These findings suggest that displacements harm workers both in the short-term and the long-term. Research suggests that, among safety net programs, unemployment insurance (UI) is the most effective at mitigating earnings losses for displaced workers, though it often fails to protect the most vulnerable workers. The massive job losses that accompanied the COVID-19 recession were met with enhanced Unemployment Insurance (UI), and that undoubtedly blunted some of the initial catastrophic effects of job displacement. However, it is not yet clear what the long-term effects will be on those who were displaced by the COVID-19 pandemic. Research suggests that policies like an expanded earned income tax credit (EITC) could also help displaced workers.

In a separate blog, we explore whether the likelihood of experiencing a job displacement and its effects on earnings vary by a worker’s race, education level, and parental income.

Footnotes

[1] Note that prior to the displacement, there are no statistically significant differences in earnings between the displaced and non-displaced workers, suggesting that the post-displacement earnings effects are due to the experience of losing a job that one had for an extended period – and losing the value of all the specific skills one had built up in that job over time – rather than because workers who will become displaced are on a fundamentally different earnings trajectory.

Kristin Butcher is Vice President and Director of Microeconomic Research at the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, or its staff.

The Brookings Institution is financed through the support of a diverse array of foundations, corporations, governments, individuals, as well as an endowment. A list of donors can be found in our annual reports published online here. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions in this report are solely those of its author(s) and are not influenced by any donation.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

The long-term economic scars of job displacements

July 21, 2022