This blog summarizes the new report “Moving up: Promoting workers’ economic mobility using network analysis“.

The promise of opportunity—and with it, economic and social mobility—is a central tenet of the American Dream. In his inaugural address, President Biden described a set of “common objects we love that define us as Americans.” The first on his list: opportunity.

However, while opportunity is omnipresent in political rhetoric and debate, there is little consensus as to what the barriers to opportunity—and mobility—in America are, let alone what we should do about them. Now, emerging from the economic devastation borne by COVID-19, and with the Biden administration’s American Jobs Plan on the horizon, there is an opportunity to turn promises into concrete action.

The American Jobs Plan hinges on two central prospects: That bold investment can create good jobs—for the present and the future—and that a targeted approach can meet workers most in need of opportunity where they are and connect them to these new jobs.

Our new report, “Moving up: Promoting workers’ economic mobility using network analysis,” focuses on helping policymakers and firms use their resources wisely to promote mobility for all Americans. We use network analysis to create a multi-dimensional map of the labor market, revealing a landscape riddled with mobility gaps and barriers. Utilizing data on hundreds of thousands of real workers’ occupational transitions, this research offers a new approach to better understand the contours of mobility. Moreover, our findings help illustrate why a multilateral approach to encouraging mobility is crucial—and that government, firms, worker organizations, and individuals all have a necessary part to play in promoting opportunity.

A crisis of mobility in America

Our research adds to a growing consensus that mobility in America is in crisis. But, as our report illustrates, these trends have not manifested equally across the labor market, with vast differences in mobility outcomes across demographics, occupations, and sectors.

Using a network map of the labor market, we identify 15 distinct occupational clusters which have stark differences in wages and mobility (Figure 1). Workers change jobs in well-defined patterns, moving within these boundaries far more frequently than they cross them: Transitions involving occupations of the same cluster are 3.6 times likelier than cross-cluster ones. Workers’ mobility prospects are shaped by what cluster they are in. The lowest median wage cluster, hospitality, for instance, offers its workers the worst prospects for upward mobility: Out of all occupational transitions from hospitality, only 36 percent are upward. That’s compared to 66 percent in the utilities and professional services sectors, two of the highest-paying and most upwardly mobile sectors.

Of the 15, we identify five distinct “sandpit” clusters in the labor market, comprising 38 million workers, within which only 25 percent of transitions are upwards. The mobility prospects of workers in low-wage occupations—which are concentrated in low-wage, low-mobility clusters—are slim. Over 10 years, only 43 percent of workers in low-wage occupations leave low-wage work. Their chances of moving up get smaller and smaller the longer they remain. Every four years, the probability of escaping low-wage work shrinks by half, with the chances reaching only 1 percent in year 10. As such, policy aimed at helping workers make it out of low-wage work ought to be paired with policy aimed at improving worker welfare in low-wage occupations, targeting workers who remain stuck.

Pathways to high-wage work exist, but access is unequal

Who gets stuck and who experiences mobility is also shaped by demographic factors. Across the labor market—regardless of education or sector—workers do not experience mobility equally. Hispanic and Black women face the lowest shares of upward transitions overall: 37 percent and 43 percent, respectively, compared to 57 percent for white men and 61 percent for Asian men. The gaps persist regardless of education: For Asian men with a bachelor’s degree or higher, 75 percent of transitions are upward—compared to only 56 percent for comparably educated Hispanic women.

These demographic gaps in mobility differ across sectors. Manufacturing has the largest racial mobility gaps, with Black and Hispanic workers seeing 14- and 18-percentage-points fewer upward transitions than their white colleagues. In government and education sectors, by contrast, mobility gaps are narrower, falling to 6 or fewer percentage points—suggesting public employment may offer more equitable access to mobility.

Even between workers starting in the same occupation, mobility prospects are shaped by demographic factors. The healthcare cluster, which accounts for 34 percent of the labor market’s total projected job growth over the next decade, offers notable opportunities for mobility due to the existence of both high- and low-wage jobs, with pathways between them. Nonetheless, many pathways and gateways are marked by gender and racial barriers: White Licensed Practical Nurses (LPNs) are more likely to transition upward into Registered Nurse (RN) positions, while Black and Hispanic LPNs are more likely to transition downward into lower-wage jobs as home health and personal care aides. Widening pathways between occupations is not enough to disrupt disparities in mobility when the pathways themselves are rife with disparities. There is a need for action at the firm level given that deficits in mobility permeate HR practices, processes, and culture.

Structural change

Nevertheless, widening mobility pathways is a critical objective. Across the labor market, stepping-stone occupations, middle-wage jobs that have long served as conduits between low- and high-wage occupations, are disappearing. We define stepping-stone occupations such that employment in them comprises 16.5 percent of total employment in 2019. According to Bureau of Labor (BLS) projections for 2029 employment, the labor market will require an additional 775,000 middle-wage stepping-stone jobs to keep their 2019 share of total employment. To escape occupations with low wages and low mobility prospects, some workers must make a cross-cluster leap to a new, more promising area of the labor market. While this is always challenging, some occupations are better skyways to mobility than others, due to their low barriers to entry and plentiful opportunities for career development, such as jobs in construction labor or IT support. Analyzing the labor market in stasis, rather than as a series of flows, misses a crucial part of the picture: the hollowing out of the labor market not only leaves workers with fewer middle-wage opportunities, but fewer ways to make it into high wage work as well.

The central challenge of our coming era is to help workers cope with technological disruption while improving mobility, reducing inequality, and restoring equal access to opportunity—so that all American workers can share in the benefits of economic growth, rising productivity, and innovation. To create a future economy that works for everyone, we must focus more on helping workers adapt and transition and ensure that workers have the chance to move up. To do that effectively, we need better tools for understanding what’s required to succeed in our dynamic, rapidly changing labor market. Likewise, given the persistent prevalence of low-wage jobs, we must double down on improving job quality and strengthening the social safety net for those who may spend their entire careers at the bottom of the income ladder.

In one sense, President Biden, in his inaugural address was correct: A belief in the value of opportunity is a unifying tenet of American life. But until we rectify the vastly unequal—by race, sex, and occupation—distribution of that opportunity, until we act to adapt our policy and economy to a changing world, until we reverse our long backslide into a two-tiered society, the enduring American promise of opportunity remains an unfulfilled one.

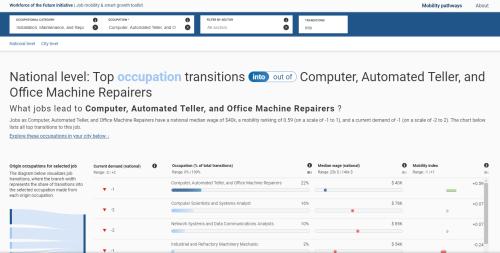

| The Workforce of the Future Mobility Pathways toolkit, using data from hundreds of thousands of real job transitions, shows how workers can advance through labor markets—featuring national and city-by-city data on wage levels, local labor demand, and job mobility rankings for 441 occupations, from retail salespeople to cooks to computer programmers. You can use the toolkit here. |

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

The American Dream in crisis: Helping low-wage workers move up to better jobs

June 14, 2021