Content from the Brookings Institution India Center is now archived. After seven years of an impactful partnership, as of September 11, 2020, Brookings India is now the Centre for Social and Economic Progress, an independent public policy institution based in India.

Sambandh Scholars Speak is a series of blog posts that feature evidence-based research on South Asia with a focus on regional studies and cross-border connectivity. The series engages with authors of recent books, articles, and reports on India and its neighbouring countries.

In this edition of our blog series, Umika Chanana interviews Dr. Anwesha Dutta on her article “Forest becomes frontline: Conservation and counter-insurgency in a space of violent conflict in Assam, Northeast India” published in Political Geography Vol. 77, 2020.

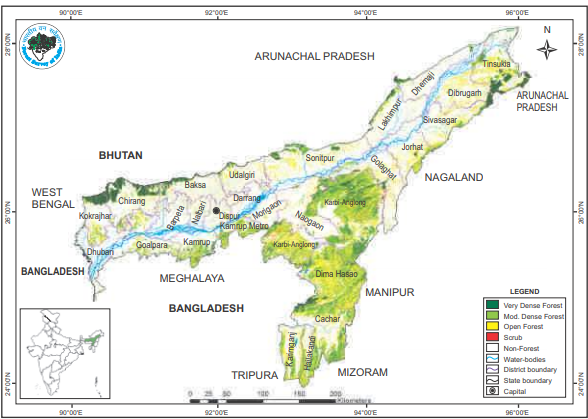

In the article [1], Dr. Anwesha Dutta construes the evolution of separatist movements that stimulates the unbridled extraction of forest resources, impacting the lives and livelihood of the local population, and also constructing headway for militarised conservation, especially across the trans-boundary region of India and Bhutan. The area is susceptible to conflict and violence (concurrent to environmental conservation) and the reserve forests in the sensitive space across the borderland act as a constant site of collision between ethnic communities and state actors. The article highlights that the maximum number of plantation drives have been carried out by the Ecological Task Force in the sensitive region of Manas, on the brink of the Indo-Bhutan border. Counter-insurgency operations that materialise in the region of dense forests have vast implications on flora and fauna, shaping uncertainty over landscape connectivity in the two countries.

Q1. The article outlines the long-drawn experience of reserved forests with respect to counter-insurgency operations across semi-porous borders with Bhutan. Having conducted extensive research and looked at the region in different phases, pre- and post-conflict, to what extent do you think open borders with Bhutan affect the movement of insurgents across forests?

I first went to Bodoland Territorial Autonomous Districts (BTAD) for four weeks in 2009 during my master’s studies and have continued to work there since. Clearly, the reserved forests- spanning from India to Bhutan- emerged as central to the processes of conflict, conservation, displacement, and rehabilitation. Over the years, a lot of academic and policy work has focused on aspects of ethnic and political violence, issues of land and demographics, displacement and so on. But the study of India-Bhutan borderlands as a space of history, shared connections, everyday forms of mobility and its role in the ongoing conflict remains to be undertaken. My research, mainly drawing on long term interactions with forest dwellers within the reserved forest in the Indo-Bhutan borderlands, found that in the heydays of the conflict in the 1990s till the early 2000s, there was quite some movement of insurgents from India into Bhutan. One is aware of operations – Rhino, Bajrang, and All Clear in the 1990s and 2000s- used to flush out insurgents. Conversations with locals revealed that insurgents still moved across borders since it was difficult for armed forces to recognize them. I was often told that they were farmers by day and insurgents by night, or that the armed forces were foreign to the land and hence unable to distinguish between locals and insurgents. Indeed, the porous forested borders affect mobility to a large extent.

Q2. In the article, you have pointed out that the insurgents are embroiled in illegal smuggling of timber and poaching activities to fund insurgency operations whilst using forests as pathways to their bases in Bhutan. How does cross-border co-operation cater to these concerns in insurgency affected areas?

Q2. In the article, you have pointed out that the insurgents are embroiled in illegal smuggling of timber and poaching activities to fund insurgency operations whilst using forests as pathways to their bases in Bhutan. How does cross-border co-operation cater to these concerns in insurgency affected areas?

The role of insurgents in forms of illegal timber smuggling and poaching has lessened over the years, especially since the creation of BTAD in 2003 and more so in recent years. This is also due to several cross-border operations between India and Bhutan, and increased patrolling and vigilance in the border areas by the Indo-Tibetan Border Force (ITBP), among others. However, the caveat to this is that often local communities who collect timber/firewood for subsistence are equated with organized syndicates operating in these areas. An interesting but obvious observation was that extractive activities increased during the times of ethnic conflict since (as I also mention in my paper) counter-insurgency continues to be a priority rather than conservation, especially during episodes of violence.

What distinguishes the Indo-Bhutan border from other borders of India with China, Pakistan, Bangladesh, etc. is the longue durée of friendly relation between India and Bhutan. In the aftermath of ethnic clashes in 2014, I was staying at the circuit house in Kokrajhar and I remember that almost every day Bhutanese officials came down for meetings with Indian officials. Moreover, this borderland scape is also characterized by the existence of informal people to people networks, civil society presence through the Indo-Bhutan Friendship Association chapter on the Indian side. These, to a large extent, address the concerns and help frizzle cross-border tensions- if and when they arise.

Q3. The Trans-boundary Manas Conservation Area (TraMCA) is an India-Bhutan collaboration to bolster regional connectivity for effective management of the ecosystem. Based on your fieldwork, in what ways do initiatives such as the TraMCA help preserve biodiversity?

Q3. The Trans-boundary Manas Conservation Area (TraMCA) is an India-Bhutan collaboration to bolster regional connectivity for effective management of the ecosystem. Based on your fieldwork, in what ways do initiatives such as the TraMCA help preserve biodiversity?

The TraMCA is indeed a good initiative conservation-wise, although it could do more to go beyond classical conservation approaches, and in making it more participatory through the inclusion of local communities. What I have also worked on, lately, is the trans-boundary water sharing between India and Bhutan through a century-old irrigation system called the jamfwi (in Bodo). There are several rivers that flow down from Bhutan into India and there are no state-provided irrigation projects in the reserved forests. Through people-to-people networks, aided by local NGOs including officials on the Bhutanese side, those residing within reserved forests now have access to water. This is also part of Oxfam’s transboundary water-sharing project. Till now, there is no formal water-sharing agreement between India and Bhutan, which makes the existing informal system precarious and uncertain. Therefore, I am in favor of transboundary resource sharing and biodiversity conservation initiatives, which are more likely to succeed on this particular borderland due to the Indo-Bhutan Friendship Treaty of 1949, which was updated in 2007. This called for the expansion of economic relations and co-operation in the fields of culture, education, science, and technology. Although biodiversity and environment are vital components, that could be added to this treaty.

Q4. Your groundwork explores multifaceted roles played by state and non-state actors vis-à-vis reserved forests. How do you think your findings have wider implications in the geographically strategic location of the northeast that shares its borders with Bhutan, Bangladesh, and Myanmar?

Q4. Your groundwork explores multifaceted roles played by state and non-state actors vis-à-vis reserved forests. How do you think your findings have wider implications in the geographically strategic location of the northeast that shares its borders with Bhutan, Bangladesh, and Myanmar?

We know that weather, water, silt, and animals are all notorious border flouters and the efforts to often enclose them forcibly has undermined the very interdependent and interconnected function of societies, ecologies, and earth systems. The Himalayan resource frontier has been conceptualized as “multi-state nations” or “multi-state margins”, indicating that geopolitics has anthropogenic impacts on local environmental integrity by slicing it into different national pieces (sovereign territories). My work brings together the assemblage of myriad actors residing in these borderlands who are impacted by everyday forms of counter-insurgency and conservation. The particulars of India-Bhutan borderlands encompassing cross border co-operation (involving communities, state and the civil society organization) shows that borderlands need not always be anxious spaces. Lessons could be learned in ways of fostering not just human forms of trans-border engagements, rather, trans-boundary biodiversity projects should be as much about people as species (plant and animals). Towards this end, my research brings to fore the notion of ‘violent environments’ and applies it to spaces in which the politics of conservation is embedded in a larger context of violent conflict, in a borderland context.

About the expert:

About the expert:

Anwesha Dutta is a post-doctoral researcher based out of Chr. Michelsen Institute, Bergen Norway. Her doctoral research used a political ecology approach to study the intersection between ethnic conflict and conservation on the India-Bhutan borderlands in Assam, India. She is currently working on multiple projects – equity sharing in wildlife conservancies in Kenya, political ecology of river-bed sand mining in India, and an ethnography of frontline forest staff in Kaziranga National Park, Assam.

Contact: [email protected]

Photo credit: Anwesha Dutta

[1] Anwesha Dutta, “Forest becomes frontline: Conservation and counter-insurgency in a space of violent conflict in Assam, Northeast India”, Political Geography, Volume 77, March 2020, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0962629819300460

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Conflict, conservation, and cooperation across the India-Bhutan border

June 22, 2020