At one time most workplace savings took place in defined-benefit plans. Employer and worker contributions to the plan were managed by investment specialists. Upon retirement workers were guaranteed a monthly pension that lasted for the rest of their lives. The success of this kind of retirement plan did not depend on workers’ ability to manage their savings. The retirement funds of an employer’s workers were pooled and collectively managed by professionals.

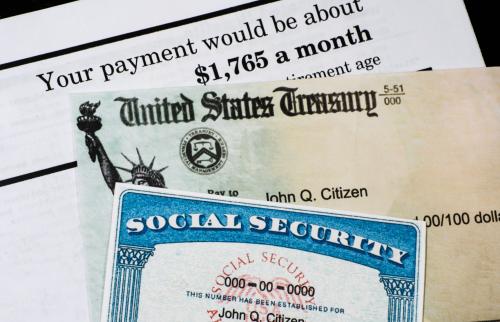

Nowadays most workers in retirement plans are enrolled in a defined-contribution plan. Although an employer ordinarily contributes to the plan, the total contribution for an individual worker is usually up to the worker and is specified as a percent of the worker’s pay. Workers must decide how to allocate their contributions and when to reallocate their savings among the investment options offered in their plan. When workers leave their jobs they are only rarely given a payout as a fixed monthly payment. They must decide how fast to withdraw their savings from their retirement account and whether to rollover their accumulated savings into a new account, such as an IRA or an annuity.

In the late 1970s the great majority of private workers enrolled in retirement plans were enrolled solely in a defined-benefit plan. Nowadays an overwhelming majority of workers enrolled in retirement plans are enrolled solely in a defined-contribution plan. In the late 1970s about 70% of pension fund assets backed the promises of defined-benefit plans. In recent years only about 30% of total pension assets are held as reserves for defined-benefit plans. The huge shift in the distribution of pension claims means that individual workers are now the principal managers of their own retirement savings. Unfortunately, there is a great deal of evidence workers do not know much about investing. As a result, many depend on the investment advice they receive from advisors.

The Department of Labor (DOL) recently issued a proposed rule that would affect the kind of financial advice that workers receive when making decisions about their retirement savings. For many financial advisors the rule would change the nature of advice they can offer to retirement savers; for some it would change the way they are compensated for giving financial advice. The proposed DOL rule would change the legal standard that applies to most financial advisors. Presently, most advisors are subject to a “suitability” standard in giving advice to their clients. This requires advisors to understand their clients’ financial situation and to recommend investments that are suitable for that situation. The DOL proposes to subject advisors to a tougher “fiduciary standard.”

A fiduciary standard requires advisors to put their clients’ financial interests first. In particular, advisors would be obliged to take into account the up-front and on-going cost of alternative investment products in making investment recommendations to retirement savers. Many advisors currently have a conflict of interest in making investment recommendations. They are paid up-front or continuing fees if they persuade clients to invest in particular investment products but not in others. As noted by the Council of Economic Advisors in a report describing the effects of advisers’ conflicts of interest, there is abundant evidence that some conflicted advisors recommend investments that are remunerative to the advisor but that reduce the expected return obtained by clients. The research showing the adverse effects of conflicts of interest on advisors’ recommendations and retirement savers’ decisions is extensive and persuasive.

A counter-argument to imposing a fiduciary standard on all advisors is that the commission system, which creates adverse incentives for advisors, is necessary in order to pay for financial advice to retirement savers, especially savers who have modest accumulations. According to this argument, even conflicted advice is better than no advice at all. This claim does not seem terribly compelling. There are alternative ways to compensate financial advisors that do not create an obvious conflict between the interests of advisors and retirement savers. For example, advisors can be paid flat hourly rates or a fixed percentage of the total retirement savings for which advice is being sought. For a large percentage of the workers who have accumulated little savings, the best financial advice is often the simplest: Save as much as you can afford, and invest the bulk of your retirement savings in a low-cost target-date retirement fund that is appropriate given your age and tolerance for risk. It should not require a hefty commission to offer this advice.

Commentary

Financial advice for retirement savers: Paying for advice without a conflict of interest

July 29, 2015