Similar to the unrealized DREAM Act, provisions of which remain in the Senate bill currently being debated, the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) offers young people brought to the United States as children without legal status the opportunity to remain in the country without fear of deportation if certain conditions are met.

Getting a job and a driver’s license are enormous opportunities in the lives of many young people who have been granted a reprieve from deportation under this program, announced just over a year ago.

More than half a million young people have applied for DACA. To date, 57 percent of applicants have qualified for this temporary status. The vast majority of the remainder are still waiting to hear.

Our preliminary analysis of the [DACA] applicants indicates that two-thirds were just 10 years old or younger when they arrived in the United States. Thirty percent were under age six at entry. Their relatively young age at arrival indicates that they have spent much of their lifetime in the United States.

Temporarily protected from deportation, those who are “DACAmented” have a reprieve, but also the worry of waiting to see if Congress can get an immigration bill passed, which would offer them a permanent legal status in the United States. If not, they face uncertain prospects if a future president cancels the policy, leaving them exposed and at risk of deportation.

But just who are the DACA youth?

Through a Freedom of Information Act request to the Department of Homeland Security, we obtained information on all DACA applicants through the first seven months of the program. Our preliminary analysis of the applicants indicates that two-thirds (67 percent) were just 10 years old or younger when they arrived in the United States. Thirty percent were under age six at entry. If anything, their relatively young age at arrival indicates that they have spent much of their lifetime in the United States.

Given that they needed to be at least 15 when they applied for DACA, this is a group that on average has lived a good part of their lives in the United States without legal status. Nonetheless, Dreamers attend American public schools and participate in the culture and history of their generation, coming of age and forging identities in the United States. But their lack of legal status has no doubt limited opportunities for many as they make the transition to adulthood.

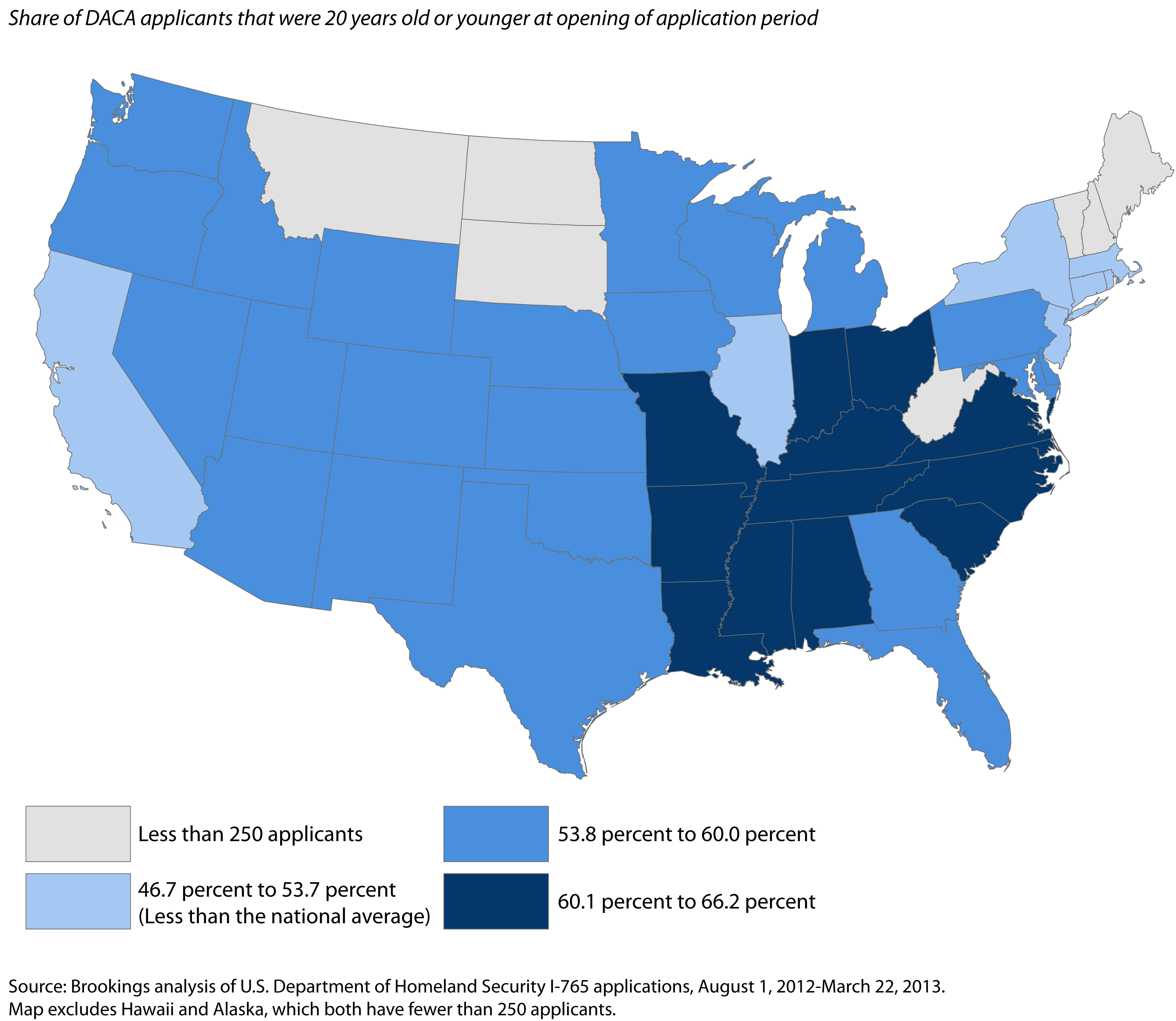

We also calculated the average age of applicants at the time they would have first been able to submit their paperwork, in August 2012. Nationally, more than half of all applicants (53.7 percent) were under age 21 when they applied. The most common year of birth? 1994, by our estimate, approximately 18 years old when the program started.

When we looked across states at age at application, we found differences in the proportion who were under age 21 at the time they applied. In states with well-established immigrant populations, like California, New York, New Jersey and Illinois, applicants tend to be on the older side of those eligible; the share of the population 20 and younger is less than the national average of 53.7 percent (See Map). In fact, in those particular states, the share hovers around 50 percent. However, these are among the states with the largest overall immigrant populations; they also have the most DACA applicants.

Some of the states with the largest shares of applicants under age 21, such as Arkansas, Indiana, Alabama and North Carolina have a fast-growing and somewhat tumultuous recent history of immigration. Other states with relatively large numbers of applications include Texas, Florida, Arizona and Georgia. They have above average shares of younger applicants, too.

In some ways it is surprising that applicants skew young. Older youth may have more awareness of what is at stake, but they may also have more obstacles. They are farther away from enrollment in school and may not have easy access to documentation of their attendance. Some are saving to be able to afford the fees. They are also more likely to have completed their schooling, putting them farther out of reach from support networks like advocacy groups that target educational institutions to recruit and assist applicants who might be eligible.

The information we have thus far shows that the DACA cohort—as of now—is primarily on the cusp of adulthood. They are at the age when their peers are finishing high school, applying for and attending college, getting training and starting jobs. Now, this group has a chance to keep up. Over the past year, the response to DACA has shown that these undocumented youth are ready to step up and pursue legal status, opening avenues to pursue their future.

It makes sense to take DACA one step further to the full legalization and citizenship proposed in the Senate bill. Blocking access to opportunity at this point keeps would be “Dreamers” from becoming full members of their communities and the rest of the country from benefiting from their economic and societal contributions.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

DACA: Coming of Age at a Time of Immigration Reform

June 19, 2013