Friday afternoons are typically the place to hide bad news, but that wasn’t this.

Late Friday, November 5th, the House of Representatives passed the Senate version of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA). The bill now goes directly to President Biden’s desk, where it will certainly become law. America finally has a generation-defining infrastructure bill—and if the reconciliation budget comes through, too, America will begin a building spree larger than what happened during the New Deal.

When landmark legislation like IIJA gets passed, it’s easy to overemphasize victories on Capitol Hill. But that’s not the case for infrastructure. Passing IIJA is only the end of the beginning.

Now the action shifts. Federal agencies like the Departments of Transportation and Energy have the enormous responsibility to implement the law, standing-up new programs and finding safe ways to quickly get money out the door. State and local officials carry an even greater burden. As the owners and operators of most infrastructure, they must design and build new assets, hire more workers, and even mobilize their own financial resources.

America finally has a generation-defining infrastructure bill—and if the reconciliation budget comes through, too, America will begin a building spree larger than what happened during the New Deal.

Remember, IIJA isn’t a stimulus bill; it’s not a singular response to a specific economic crisis. IIJA represents a longer-term patient approach to rebuilding American competitiveness through infrastructure.

It’s going to be a busy few months inside Washington and across the country as IIJA implementation begins and items like the reconciliation budget continue to move. Here are four key elements to keep in mind as we all try to make sense of this busy time.

IIJA has more breadth than typical federal infrastructure bills

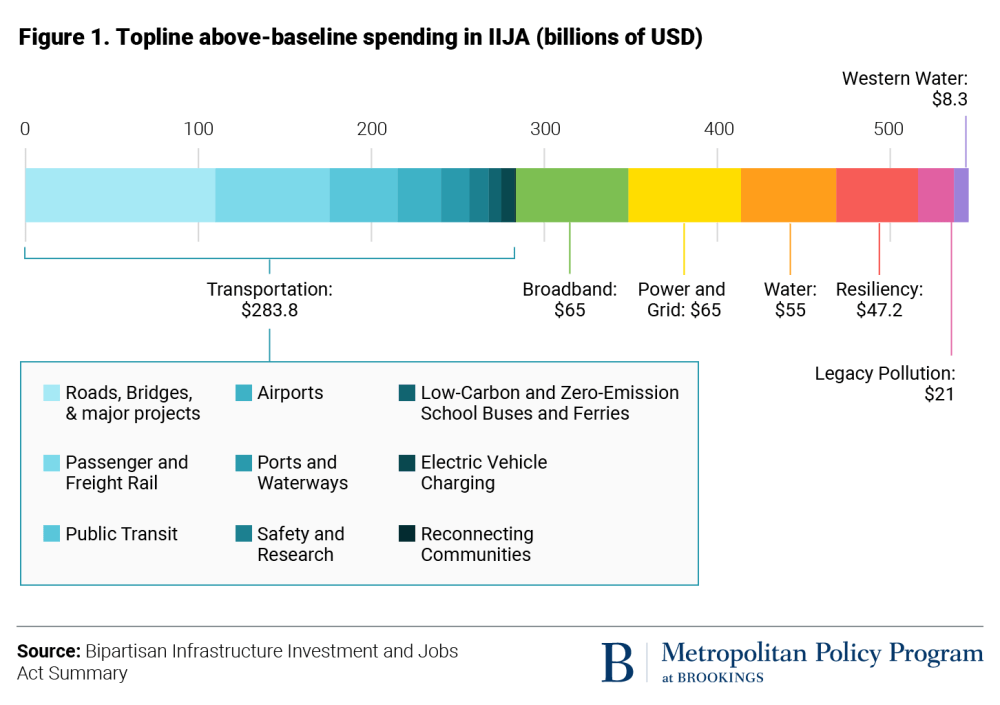

By almost any measure, IIJA is enormous. The roughly $1.2 trillion bill contains an estimated $550 billion in new spending above baseline levels. This spending touches every sector of infrastructure, from transportation and water to energy, broadband, and the resilience and rehabilitation of our nation’s natural resources. While topline numbers from Senate summaries show us the general trends in funding distribution—over half of new spending is transportation-focused—the magnitude of these investments warrants a deeper dive.

The bill’s breadth is also considerable, containing policy reforms and funding for hundreds of programs. Many of these programs have been around for decades—like the Clean Water and Drinking Water State Revolving Funds, into which IIJA pours $11.7 billion each year—and are now funded at higher levels. New kinds of investments are also being channeled through these existing systems, like the additional $15 billion for the Drinking Water State Revolving Fund appropriated solely for lead service line replacement.

Entirely new programs have been authorized to address essential gaps in our nation’s current infrastructure funding, like resilience. The Promoting Resilient Operations for Transformative, Efficient and Cost Saving Transportation (PROTECT) program, for instance, will provide $7.3 billion in formula funding, in addition to $1.4 billion of competitive grant funding appropriated through the Highway Trust Fund. The $6.4 billion new Carbon Reduction Program within the Federal Aid Highway Program will channel formula funding into bicycle and pedestrian trails, transit, and other energy-efficient transportation investments. Meanwhile, IIJA invests an estimated $15 billion in electric vehicle chargers and electric buses.

The bill is also a first-of-its-kind comprehensive investment in broadband deployment, equity, and affordability. IIJA does the important work of adopting formal language and definitions to shape our country’s approach to addressing the digital divide. It also invests to overcome the divide. For example, there is $48.2 billion in broadband funding appropriated to the National Telecommunications and Information Administration to address middle mile deployment, digital equity, and affordability. Funds are also appropriated across several agencies to address growing cybersecurity concerns, as well as to invest in climate-focused environmental monitoring and R&D.

These are just a sampling of IIJA’s programs. Over the coming weeks, we will publish more details to help others explore the bill’s critical details.

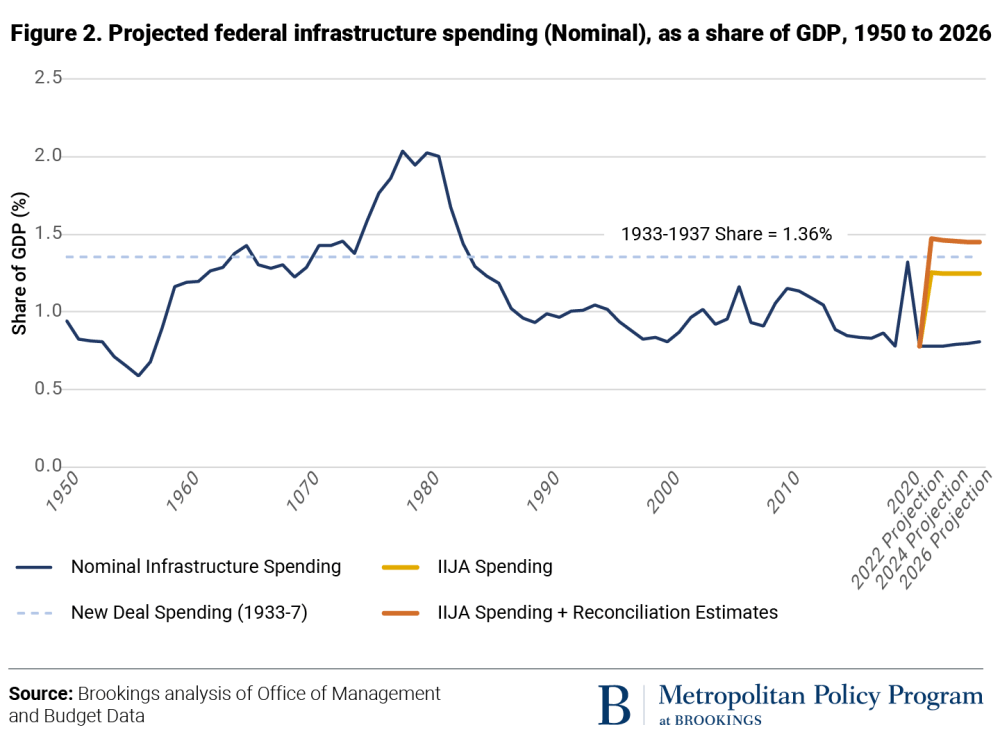

Combined, IIJA and the reconciliation would be the biggest federal infrastructure investment in half-a-century

It’s worth pausing to consider just how much bigger the total federal investment program will be if both IIJA and the reconciliation budget become law. The current House reconciliation version proposes roughly $500 billion in new infrastructure spending over 10 years. Combined with IIJA, the federal government could be spending $160 billion above baseline for the next 5 years. That would push federal spending above New Deal investments in infrastructure—as measured by federal spending as a percentage of GDP—but likely to fall short of the historic federal peak around the late 1970s.

The bills are also a fundamental signal of our national political climate. While both bills make enormous investments in American infrastructure, from capital assets and conservation efforts to workforce systems and research programs, IIJA’s programming represents more bipartisan concepts. By contrast, the reconciliation budget—which will be written solely by Democratic Party members—includes far larger commitments to climate change mitigation and adaptation. Not all states and communities would follow this partisan distinction, but the federal legislative process creates an unmistakable data point about where the two major political parties stand today.

It will often take years to start seeing IIJA’s projects in our communities

IIJA is not another stimulus effort; it represents a generational shift in how (and what types of) projects get done. Federal agencies—from DOT to DOE to EPA—have to oversee the surge in funding, including administering new grants and designing new programs. States and localities—from transportation departments to water utilities—have to identify and execute needed projects on the ground. And this federal, state, and local coordination all comes amid continued challenges overseeing other expanded funding from the American Rescue Plan earlier this year.

Most projects will not happen overnight. The pace at which federal funds reach different places nationally depends on the types of projects pursued and the types of programs channeling resources to these projects. As we learned during the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act a decade ago, “state of good repair” projects, such as resurfacing or improving roads, happen faster than more sophisticated capital projects, such as new system expansions. Funding in existing federal programs, including those distributed by formula, also tends to move faster than funding in new competitive grant programs, which involve new rulemaking. For instance, estimates from the Congressional Budget Office and Congressional Research Service show that DOT only spent about 9% of its allocated ARRA funding in the first six months and around half of its funding in the first 18 months.

The public sector must grow to manage this level of new investment

Any time governments suddenly increase spending—especially when it could easily exceed $100 or $200 billion in a given year—it is likely to have profound impacts on internal government operations, the demand for labor, and the related supply chains. That will certainly be the case with IIJA and only grow more urgent if the reconciliation budget passes.

IIJA launches multiple new federal programs, all of which will require internal planning, internal and public review, and hiring staff and building knowledge resources to stand-up new operations—all before any services like grant agreements and technical expertise are produced. It’s an enormous undertaking. Meanwhile, state and local officials must ensure their operations are ready to handle the influx of new federal funding. For example, with so many new competitive grant programs, do officials and their teams have the data and community support to submit applications?

All this new programming will demand more workers, too. All three levels of government must be ready to hire for a sweeping set of occupations: budget experts, various construction workers and skilled tradespeople, conservationists and environmental engineers, and so on. Human resource departments may need to grow just to make all the hires. Meanwhile, public agencies will be competing for scarce talent with the private sector. More good-paying jobs is a good thing, but it raises the urgency to expand the infrastructure-related talent pipeline.

IIJA also will mean greater aggregate demand for input materials, in some cases creating greater competition between government, businesses, and households for the same goods. Building new physical infrastructure will require various steel products, cement, lumber, and other material inputs. Modernizing federal equipment includes buying new vehicles. Weatherization programs will require similar inputs to many real estate construction projects. New management systems and equipment requires new processors and other computing equipment. With global supply chains still under stress, the timing of when infrastructure orders start to increase merits a close watch.

The work is just starting

There’s a reason infrastructure advocates, economists, business leaders, community-based organizations, and others have continued to call on Congress to pass a major, comprehensive infrastructure package. The country needs to invest in itself, to stay competitive today and into the future.

Regardless of how enormous the implementation lift may be, Congress has now done their part. America is ready to invest in itself again, and the investment amount is only likely to grow. They may have dropped the news on a Friday afternoon, but the legacy of this bill should make it hard to forget.

Commentary

America has an infrastructure bill. What happens next?

November 9, 2021