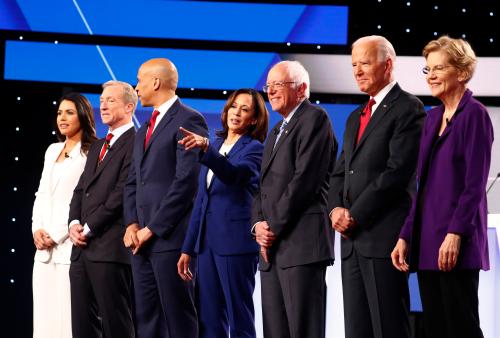

There is a heated debate going on in America right now about what the future of work will look like. Thousands of news stories have covered the potential impacts experts believe artificial intelligence, automation, and robots may have on jobs. Numerous conferences focus on the future of work and feature discussions with technology leaders, academics, and industry executives. The future of work is even a trending theme in the 2020 presidential race and the subject of a question in the Democratic presidential debate earlier this fall.

Ironically, the voices of workers themselves are largely absent from the debates, decisions, and discussions that will shape their future. Darren Walker, president of the Ford Foundation, lamented, “Too often, discussions about the future of work center on technology rather than on the people who will be affected by it.”

Ironically, the voices of workers themselves are largely absent from the debates, decisions, and discussions that will shape their future.

As a new David M. Rubenstein Fellow at Brookings, my scholarship with the Metropolitan Policy Program seeks to turn the future-of-work paradigm on its head. At the center of my research are the workers who are too often overlooked—including women, Black, Latino or Hispanic, and low-wage workers—and brings their voices and perspectives into policy discussions they are often excluded from. My work includes interviewing workers at greatest risk of technology-induced change to better understand their lives, struggles, and perspectives, and I draw insights from these interviews to inform policy solutions.

How “the future of work” sidelines worker voices

This blind spot that exists toward these vulnerable workers reflects in part the long-run erosion of worker power and the precipitous decline in the reach of unions, rising inequality, the fissuring of the workplace, and the impact of globalization and technology on the “hollowing out” of the job market. Many workers who hold jobs most susceptible to automation—such as food service, retail, and office support workers—lack union membership and a clear representative to speak on their behalf.

Moreover, the public narrative around the future of work is limited by a constricted mental model of who the worker even is. The lion’s share of media coverage focuses on a narrow demographic of white men in blue-collar manufacturing and transportation jobs. Yet this popular conception is at odds with data that shows “the vulnerable are the most vulnerable,” as my colleague Mark Muro points out. Low-wage workers, already struggling with economic precarity, face a disproportionate risk of displacement, as do Black and Latino or Hispanic workers. Women are rarely considered, despite their overrepresentation in many automation-affected occupations.

The result is a lopsided conversation and policy process, with many groups of vulnerable workers lacking a seat at the table.

Why worker voice matters

Because they’re excluded from these conversations and decisions, workers lack agency to shape the direction of technology in ways that can complement their work and allow them to share in its benefits. For instance, in the rollout of new information technology at Kaiser Permanente in the early 2000s, union engagement in decisionmaking secured job and wage protections, training guarantees, and provided a channel for workers to have a say in how the technology would be deployed and used. As a side benefit, this also resulted in improved clinic outcomes.

Because they’re excluded from these conversations and decisions, workers lack agency to shape the direction of technology in ways that can complement their work and allow them to share in its benefits.

Policy effectiveness can also suffer from lack of worker engagement. Without better understanding those who are at greatest risk of disruption, well-intentioned innovators, policymakers, and thought leaders risk proposing solutions that are at odds with the challenges and realities workers face. Technology doesn’t happen in a vacuum—the context of workers’ lives and the many interconnected structural and systemic forces that shape their opportunities are critical to consider. Many of the workers most at risk of automation already shoulder the greatest burdens of instability and insecurity.

Without a larger appreciation for the precarious economic lives that workers navigate, policymakers’ expectations about the ease of workers’ job transitions and “upskilling” amount to little more than wishful thinking. Adequately preparing the most vulnerable workers for the future of work requires addressing the inequality, power imbalances, and market failures that hold them back from prosperity today.

Shifting the paradigm: Starting with worker voice

Scholarship and thought leadership have an important role to play in helping to correct these imbalances and improve the visibility of workers. Human-centered research is one way scholars can bring the voice and lived experiences of workers into popular debates and policy dialogues.

Over the past year at New America, with my colleague Amanda Lenhart, I led a human-centered research initiative that sent our team to four regions across the country to interview a diverse group of cashiers, grocery and retail workers, fast food workers, and clerical and administrative staff. Most of these workers were women, and more than half were Black or Latino or Hispanic. We learned about their lives, their struggles, what they want from their work, their experience with technology, and their aspirations for the future. We also learned the many ways that workplaces, the social safety net, higher education, and broader talent development ecosystems are—or, more often, are not—meeting their needs. In the forthcoming report, which will be released on November 21st, we share the voices of these workers and discuss their implications for the future of work.

In the coming months, my Brookings Metro colleagues and I will build on this human-centered approach, bringing the stories and voices of workers into policymaking discussions and scholarship on the future of work. These insights will allow us to think more broadly about larger policy reforms that are needed, including how to:

- Improve the present reality—and future—of work for low-wage workers, and strengthen their voice and power in the workplace;

- Activate and develop the often-untapped talent of workers through a more user-friendly and equitable talent development ecosystem;

- Better support workers whose jobs are vulnerable to change, including low-wage workers, Black and Latino or Hispanic workers, women, younger and older workers, and middle-class workers who risk displacement;

- Strengthen the quality of the jobs of the future, especially on dimensions that workers value most;

- Better define what good and bad automation looks like from the perspective of workers, and explore best practices for employer engagement of workers in decisions about the design of technology; and

- Reimagine the safety net to create new opportunities for enhanced economic stability that enable workers to weather disruptions and change.

Often, this will entail challenging the prevailing future-of-work myths that are at odds with the realities and perspectives of workers at the forefront of change (Spoiler alert: there are many!). In my next post, I will explore a ubiquitous example of a “so-so” technology, the very strong views of workers about this technology, and its implications for the future of work.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Putting the worker in the future of work

November 19, 2019