People urging more aggressive action on climate change often use children in their rhetoric: “we need to leave a better planet for our children,” “we owe it to the next generation to act,” etc. Earlier this year, two dozen children went so far as to sue the U.S. government for failing to act. “This is an intergenerational issue,” said James Hansen, a former NASA scientist supporting the lawsuit. “Our actions will affect our grandchildren and their children.”

The latest issue of the journal The Future of Children, a joint publication of Brookings and Princeton University, goes beyond the usual rhetoric and provides a detailed analysis of the impact of climate change on children’s wellbeing.

A hotter planet means worse child wellbeing

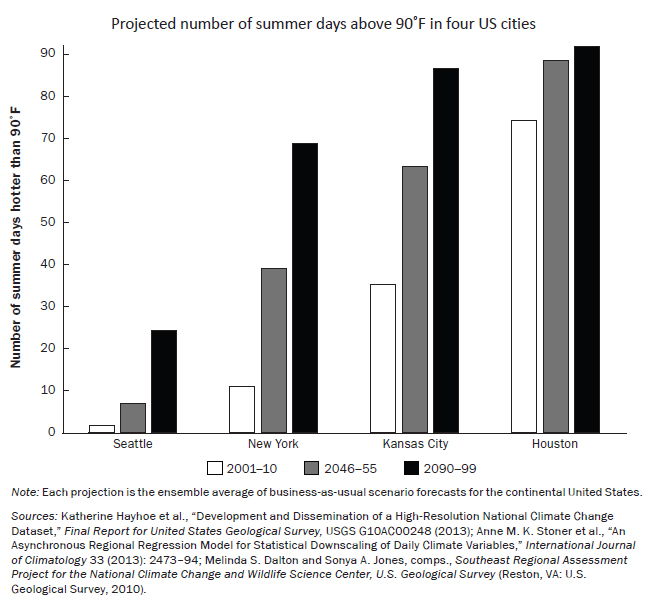

Global temperatures are rising. Based on current trends, many Americans will live in hotter cities:

Extreme heat is associated with a rise in infant deaths, physical birth defects, delayed brain development, and nervous system problems, suggest Joshua Graff Zivin and Jeffrey Shrader in their contribution to the new volume. Excess heat can also reduce human capital development by damaging learning.

The direct effects of heat are just one way climate change can have an impact on children. Contributors to the volume examine a range of risks, including:

- the effect of extreme weather on political conflict and violence

- greater pollution leading to increased asthma rates

- the effects of more powerful and more frequent natural disasters on children’s nutrition and physical health

- greater pollution—specifically fine particulates—affecting academic test scores

Mitigating the impact of climate change on child wellbeing

The priority for public policy should be to slow temperature rises by curbing greenhouse gas emissions. A carbon tax would be a simple and effective intervention, as our colleague Adele Morris has argued. But given that some heating is occurring already, policy makers should also be considering mitigation measures, especially to protect children.

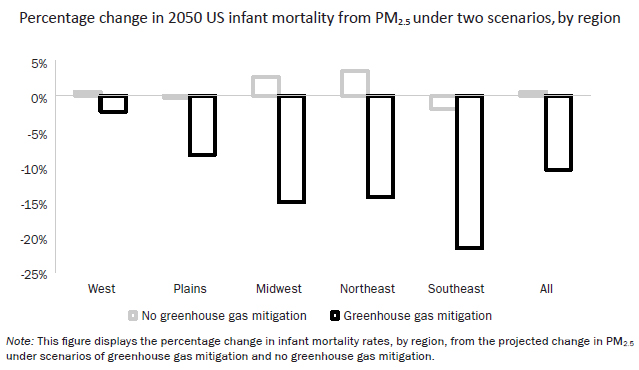

Allison S. Larr and Matthew Neidell report that increases in fine particulate matter (PM2.5) affect the lungs and the heart and can cause respiratory problems, asthma, heart attacks, and an irregular heartbeat. They then examine the impact of mitigation policies, such as the EPA’s new Clean Power Plan, on infant mortality. Such mitigation measures could result in around 10 percent fewer infant deaths in the U.S., equivalent to 2,500 lives saved. The greatest benefits, they find, would be felt in the Southeastern region:

Of course mitigation comes at a cost, which would be paid mostly by the current generation of taxpayers. But acting now is cheaper than acting later. We may not have the luxury of time in any case; the rising temperature already has implications for children’s health and wellbeing.

Ron Haskins, Janet Currie, and Olivier Deschênes, in a policy brief accompanying the volume, highlight the link between climate change and the spread of disease-carrying mosquitoes, including Aedes aegypti which carries the Zika virus. There are steps we can take to avert climate change and to mitigate its effects. The question is whether we are willing to pay the price.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

The world’s children are already suffering from climate change

May 4, 2016