Americans live near fewer jobs than they used to, which may be bad news for social mobility. Our recent report, “The growing distance between people and jobs in metropolitan America,” had one straightforward implication: commutes are getting longer. This puts more strain on infrastructure and more carbon into the atmosphere. But there are implications for opportunity, too.

Local jobs = opportunity

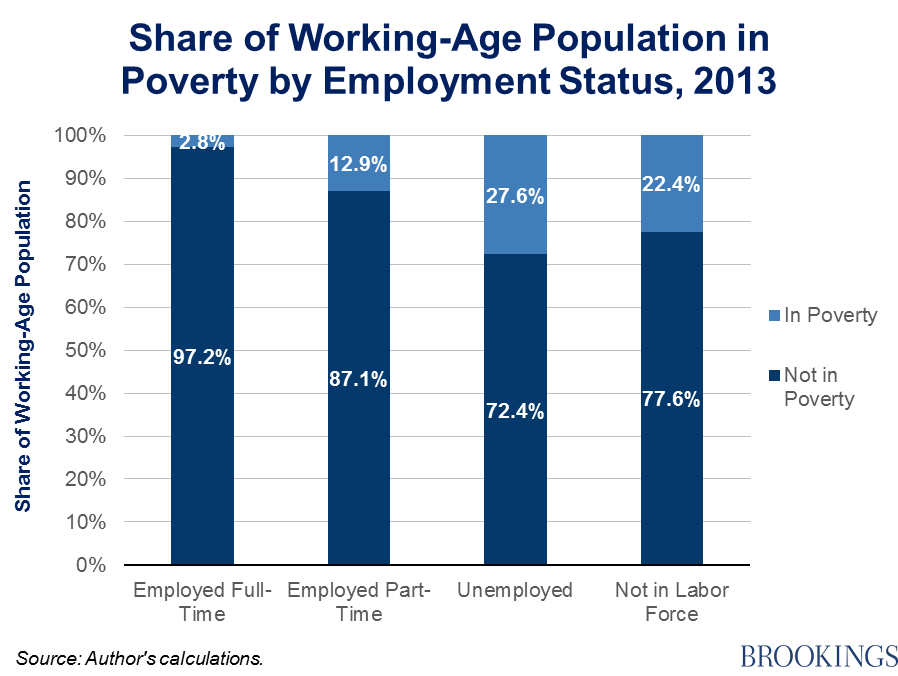

Having jobs nearby increases individuals’ likelihood of employment, and also tends to reduce the lengths of jobless spells. While employment doesn’t automatically protect against poverty, it makes a huge difference to the risk:

Proximity to employment is especially important for low-income workers, who may have fewer choices about where to live, or how to get to work (given the cost of owning and maintaining a car). Finally, nearby jobs also support the local tax base for schools and other critical public services that support social mobility.

Jobs are declining faster near low-income people

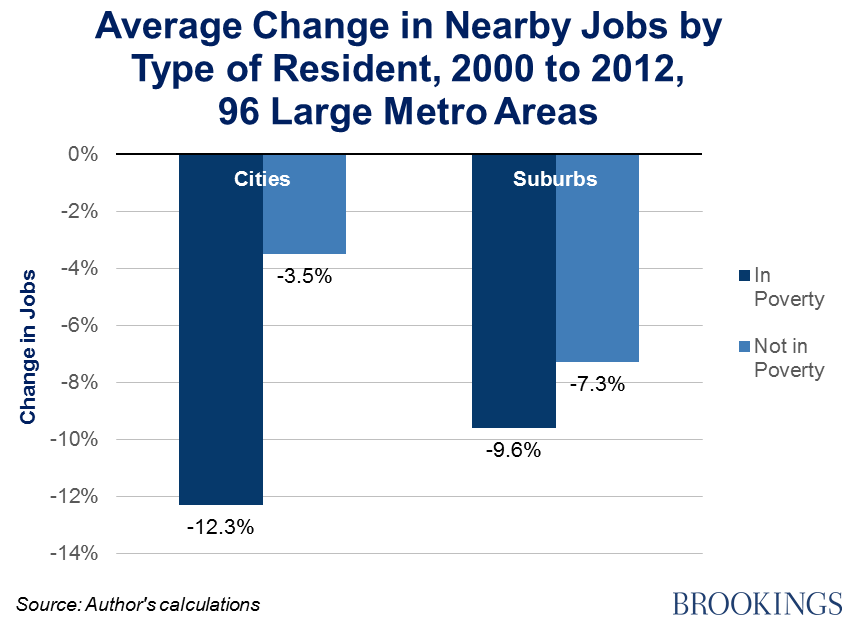

Unfortunately, over the past decade-plus, jobs within an average commute distance dropped faster for the poor residents of both cities and suburbs:

Between 2000 and 2012, poverty grew and re-concentrated in parts of metropolitan areas that were farther from jobs, particularly in suburbs, which are now home to more than half of the poor residents of the country’s 100 largest metro areas.

There is growing evidence that place matters for upward mobility. A landmark 2014 study by Raj Chetty and others found that intergenerational social mobility varies significantly across regions. Newer work by the same team suggests that the places in which children grow up independently affect their future earnings potential.

Atlanta and Seattle: A study in contrasts

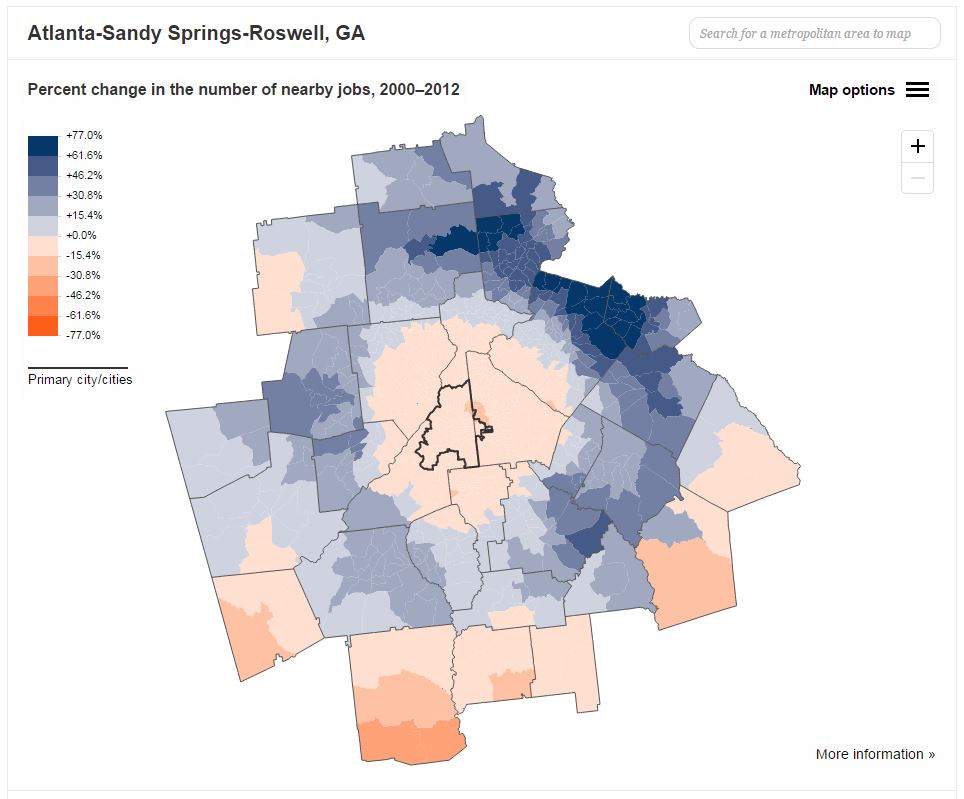

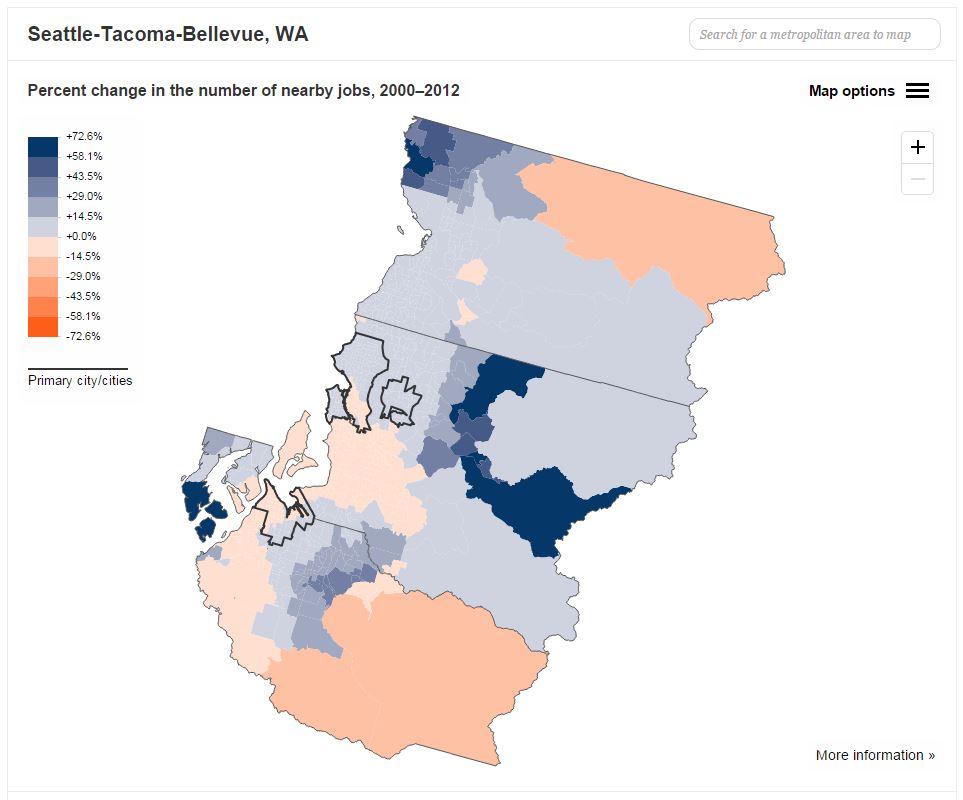

Chetty and colleagues found that a child born at the 25th percentile of income in Seattle experienced a 12 percent earnings bump relative to the national average by age 26. In Atlanta, a child born into the same part of the income distribution earned 8 percent less than the national average as an adult. The researchers found that racial and income segregation, and long commute times, explained much of the difference in mobility across these and other areas.

Recent trends in job location within Seattle and Atlanta may also explain these mobility differences. In metropolitan Atlanta, the average resident of a poor neighborhood saw nearby jobs decline by 34 percent from 2000 to 2012. In metropolitan Seattle, by contrast, the decline for residents of poor neighborhoods was a more modest 9 percent. As the maps below illustrate these trends also vary within regions:

Chetty: For more social mobility, think local

As Raj Chetty argued at a recent Brookings event, we must tackle social mobility at a local level, not just a national one. That must include connecting the residents of low-income neighborhoods to job opportunities in the broader region, as well as attracting better options locally. Improving proximity to jobs alone certainly won’t tackle our social mobility challenges, but it can ameliorate problems like segregation, concentrated poverty, and low-density sprawl that pose real barriers to economic progress for low-income kids and families.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Close to home: Social mobility and the growing distance between people and jobs

June 9, 2015