Americans are brought up to believe that a college degree is a ticket to a better life. And it is—for some. But if postsecondary education is supposed to be our engine of social mobility, it is in serious need of a tune-up.

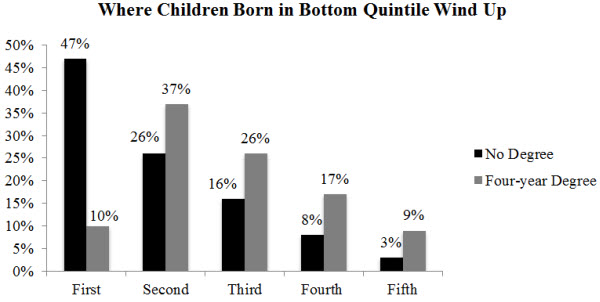

First, the good news: college graduates are much more likely to climb the economic ladder. Researchers at Pew have shown that children born in the lowest income quintile who do not earn a four-year degree are four times as likely to wind up in the bottom (47%) as those who earn a four-year degree (10%).

Source: Pew Economic Mobility Project, 2012

Now, the bad: the college payoff only accrues to those who finish a degree, and very few low-income people make it that far. According to a National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) study that followed a cohort of American students from their sophomore year in high school in 2002 through 2012, 14.5% of students in the lowest socioeconomic quartile earned a bachelor’s degree over ten years (an additional 8.2% earned associate’s degrees). 61% of students in the top income quartile earned a four-year degree over that period.

In an analysis of attainment trends since the 1960s, Martha Bailey and Susan Dynarski found that these gaps have actually grown over time.

All income groups have made gains over the past fifty years, but those gains were smallest among children from the lowest income quartile, where four-year degree attainment rose from five percent among those born in the 1960s to nine percent among those born in the 1980s.

In other words, our system of postsecondary education does promote social mobility, but only for the small segment of low-income Americans who actually finish a credential.

Much of the blame lies with the K-12 system, which often fails to prepare graduates for the rigors of college-level work. But part of the problem stems from the way federal grant and loan programs have encouraged enrollment in any college and at any cost. Students with a high school diploma can take their aid money to any accredited college regardless of whether they are prepared for college-level work or whether the college provides a good education. These policies have served colleges quite well, rewarding them for enrollments but providing them with little incentive to keep tuition prices low or ensure that students complete their degrees.

The result: the feds spend more on student aid each year but are powerless to check the growth in tuition or stop the flow of money and students to low-quality colleges. Enrollment increases, but completion rates remain stagnant. At the same time, options like apprenticeships and vocational training are marginalized and treated as a last resort despite evidence that they are effective paths to good jobs.

We can do better. Tomorrow’s blog will explain how.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Does College Really Improve Social Mobility?

February 11, 2014