President Joe Biden’s first “Summit for Democracy” is an opportunity for the United States to highlight civil liberties, freedom of conscience, and peaceful dissent at a moment in which democracy is in a fragile state around the world. Democracy is the only political system which can protect these freedoms: For authoritarian regimes of any form — single-party regimes like China, personalist dictatorships like Russia, or absolute monarchies like Saudi Arabia — criticism, mobilization, and dissent are no less than fundamental threats to the ruling order. The U.S. has long had an inconsistent record of democracy promotion around the world, and the record of democracy within the United States is uneven as well. The Biden administration views the work of the summit as building strategies to strengthen and defend democracies — the United States included — against authoritarianism.

The Summit for Democracy, however, has a larger geopolitical ambition. It reflects a prominent view within the Biden administration that assembling a global coalition of democracies can counter China’s rise and continued Russian aggression. There are good reasons to emphasize the common interests of new and established democracies, but the geopolitical ambitions of the Summit for Democracy are bound to disappoint.

To see why, it helps to distinguish between a country’s political regime and its foreign policy objectives. As Jessica Chen Weiss and I recently argued in Foreign Affairs, Chinese foreign policy is fundamentally goal-oriented and pragmatic rather than ideological. Although the Xi Jinping regime is currently engaged in a thoroughgoing defense of single-party strongman rule within China, it does not have a preference for authoritarianism outside of the country (of course, the regime considers Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan to be integral parts of China, and hence it does prefer authoritarianism in these territories as well). China’s most important strategic rival in the South China Sea region is Vietnam, which is itself a single-party authoritarian regime just like China.

The case of Russia is different: One may plausibly argue that Vladimir Putin’s regime believes that democracy in the United States and Europe threatens Russia’s national interests. But even in this case, we must be careful not to confuse a Russian strategy of foreign election interference with Russian foreign policy objectives. Russia, like China, can find common cause with any regime — democratic or authoritarian — whose policy stance is compatible with its perceived national interest.

A second reason why the Summit for Democracy may prove ineffective is that it is not responsive to the general issues of governance and economic performance that matter for mass publics around the world. Even if it were true that democracies are more likely to deliver sustained economic growth or more equitable societies — and the evidence on this is far from decisive — cases like Singapore since 1965, China since 1978, and Vietnam since 1986 demonstrate that there do exist authoritarian models for rapid economic growth and widely-shared improvements in material wellbeing.

The existence of authoritarian paths to economic prosperity makes it hard for democracy’s defenders to argue that democracy delivers better material outcomes. A regime such as China’s need not argue that there exists an exportable “China model” for others to emulate. Instead, it can simply observe that authoritarianism is not incompatible with prosperity. Any Summit for Democracy that pitches democratic regimes as better able to battle corruption — a key pillar of the Biden administration’s case for democracy — will raise similar concerns. The anti-corruption efforts of the Xi Jinping regime and China’s results-oriented focus on infrastructural development stand in sharp contrast to the rampant money politics in fragile democracies like Indonesia and the Philippines.

The key economic issue for many countries where democracy is in peril — especially those middle-income countries in Asia, Africa, and Latin America with relatively short histories of democratic rule — comes down to governance. Focusing on democracy as a solution to inequality, corruption, and ineffective economic management simply will not resonate with the summit’s intended audience.

The Summit for Democracy will be most effective if it remains focused on strengthening and defending democracy rather than constructing a dichotomy between the world’s democracies and their authoritarian counterparts. It would also be a mistake to focus on corruption, economic performance, and material prosperity as areas in which democracies can outperform authoritarian regimes.

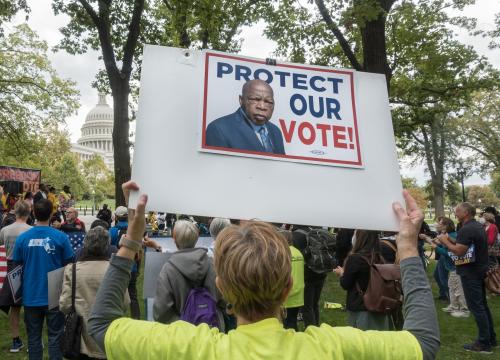

The case for democracy is simple: Democracy is the only political system that institutionalizes protections for minority voices while also protecting the rights of journalists, citizens, and opposition leaders to criticize their government.

Authoritarian leaders can promise the same protections, but their political institutions mean that any such promises are not credible. The political criticism and meaningful dissent that democracies encourage is an existential threat to any authoritarian regime.

Whatever the weakness of American democracy, past and present, the Biden administration can hold up values of liberty, dissent, contestation, and participation as both uniquely democratic and worthy of defense. To the extent that any democracy fails to deliver on these fronts, it should be strengthened. And to its credit, the Biden administration appears clear-eyed about the challenges facing democracy around the world, and here at home.

This, then, ought to be the focus of Biden’s Summit for Democracy: identifying threats to democracy and ways to strengthen existing regimes by investing in freedoms of conscience, mobilization, and dissent for all. This work ought to start at home, not least because it is essential work to do in a moment of high partisan polarization. If American democracy continues to wobble, it will have global repercussions.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Biden’s Summit for Democracy should focus on rights, not economics and geopolitics

November 22, 2021