The United States and Europe must defend liberal democracy globally by first making sure that their own democratic systems live up to their own principles, writes Constanze Stelzenmüller. This post originally appeared in the Financial Times.

One of President-elect Joe Biden’s promises is that the US will recommit itself to defending democracy in the world, together with other democratic allies. The EU, it appears, plans to firmly embrace this proposal, with a particular focus on presenting a united front to China.

Yet criticizing Beijing’s mass internment of Muslim Uighurs — or the Kremlin’s attempts to manipulate elections — draws accusations of hypocrisy at a time when many western governments struggle to convince their citizens that representative democracy remains the most trustworthy way to deliver good governance. If the transatlantic alliance is to hold its own in competition with illiberal authoritarian rivals, its members had better fix their democratic problems at home. But how?

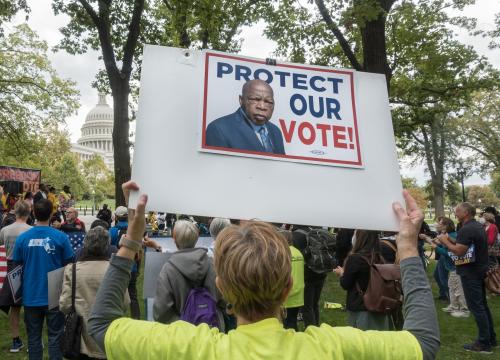

Granted, in the context of a decade of global democratic recession, the US and Europe still look quite respectable on the surface. The US presidential election last month was in many ways a triumph of democracy: Americans saw historic voter turnout, a process that broadly worked and officials and judges who refused to be intimidated. In Europe, populists hoping to exploit the Covid-19 pandemic to stoke fear and polarization have instead seen voters support centrist governments and fact-based policies.

Yet it is also true that the widespread commitment to liberal democracy — a foundational value of the west — is under fire. The fact that, in some cases, the attacks come from opposition parties within the political system is no cause for complacency.

In Germany, for example, the hard-right Alternative for Germany has been plateauing in the polls at around 10 per cent, and its leadership is mired in shambolic infighting. But it continues to wage a quiet and disciplined campaign to undermine and delegitimize democratic institutions. In France, Marine Le Pen, the leader of the far-right National Rally, remains a serious contender in the 2022 presidential election.

Elsewhere, in Hungary, Poland and Turkey, the authoritarians are in government and have used their positions to change the rules of governance in order to expand or perpetuate their hold on power. And in the US, the alliance’s anchor democracy, an outgoing president is claiming against all evidence and with the support of his party’s leadership that a massive fraud has denied him an election victory.

This democratic backsliding undercuts the cohesion of Nato at a time when conflicts around the world are heating up. It undermines trust between allies, limits intelligence sharing and reduces the effectiveness of diplomacy, deterrence and operations.

As for the EU, which the incoming US administration (unlike its predecessor) sees as a key provider of diplomatic and economic leverage, its budget is being blocked by Budapest and Warsaw in a fight over the rule of law. All this allows adversaries to exploit the west’s divisions — and gives them a welcome pretext to dismiss critiques of their own failings.

The transatlantic alliance, born out of the crucible of the second world war and the Holocaust, always had liberal democracy at its heart. For decades, the American security umbrella enabled the conditions for stable representative governance to take root in Europe: functioning states, open market economies, inclusive social contracts. Yet when some Nato member states took authoritarian turns — as happened in Greece, Portugal and Turkey — others turned a blind eye. Our allies’ domestic affairs, it was held, were none of our business.

This has to change. The alliance is based on the principle that the security of one member is the security of all. The 2008 financial crisis and its long aftermath taught us a hard lesson: in an interdependent world, the vulnerability of one is the vulnerability of all. And security today begins with resilient domestic governance.

Americans, Canadians and Europeans must now help each other think through how their own democracies can be made fit for purpose in an age of great power competition and deepening global networks. State institutions must be able to do their job — providing public goods — effectively and free from political interference or corruption. Economies must be made fairer, to minimize the kind of structural inequity that fuels popular grievances. Social and racial injustices, as well as the toxic legacy of slavery and colonialism, must be tackled head-on.

In short, we must live up to our own principles again. Then, and only then, can we offer others advice about democracy.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

The West must live up to its own principles on democracy

December 3, 2020