In the dark, all swans are black.

The worst time for prognosticating is the middle of a systemic shock. Because chaos and noise are high, almost any alternative future seems imaginable when the status quo is in shock.

Our brains, which are so skilled at synthesizing lots of complex information, are ironically one of the biggest barriers to good forecasting in these times. Amidst great uncertainty, we often select mental models that feel most convenient and least disruptive to favored futures. People who have been imagining radical change, such as completely new patterns of energy consumption, see opportunity in the chaos and forecast those futures. People operating legacy systems see fiscal bloodshed and imagine an opposite future — quick returns to old ways and incumbents. True crisis, like today, is unfamiliar; even for expert forecasters, it is hard to update mental models with analogous real-world experience.

All these errors in forecasting are on display in the energy system today — shocked by pandemic and, in the oil markets, shocked again by a Saudi-Russian war over market share.

When the pandemic abates, a close look at the fundamentals suggest that little will change overall in the energy system. Demand for energy services will abate for a bit, then recover. However, pecking orders will change a lot. In oil, American shale suppliers will be hammered while the core of OPEC (Saudi Arabia and Abu Dhabi, plus perhaps Russia) will have more control — but at a huge fiscal cost. In electricity, reliable firms will remain on top. Consolidation of weak into stronger, bigger firms is likely across the industry.

The most interesting change in pecking order is likely between state and markets. For five decades (longer, if you count differently) markets have been on the rise. Where states demonstrate they can be trusted, the state seems likely to emerge on top.

The known unknowns

The most severe impacts of the pandemic on the energy system have been felt in the oil industry, with causes and effects widely known. For oil, demand has cratered — ClearView Energy Partners estimated last weekend that demand was down about one-quarter and still falling. The shock of those lost 24 million barrels per day (mbpd) is magnified, of course, by another 4 mbpd from the Russia-Saudi price war. The result: 99-cent gasoline is back in parts of America, but nobody is driving. When demand hits bottom and starts recovery is hard to say. From today’s vantage point, recovery looks likely to start where the pandemic began: China. Some factories are back online with exports resuming, tentatively.

In all this, the knowns are that the market reflects the imbalance of supply and demand. When inventories accumulate, as they are today, prices crater. While Russia is the official target of Saudi ire — in the past, the Saudis have dumped oil on the global market to punish producers that aren’t behaving as the cartel boss expects — the really big losers will be in America. Right now, individual shale producers aren’t cutting back — each, thinking for itself, is eking out whatever cash is feasible before the industry, as a whole, falls off a financial cliff. Drilling has nearly stopped, and shale producers will probably contract more than 1 mpd over the next year from the natural decline of existing wells and the lack of cash for drilling new holes.

Consolidation of the industry around lower production and fewer large owners is likely.

Bankruptcies and unemployment across the U.S. oil patch will be swift because smaller drillers were already in precarious financial shape; consolidation of the industry around lower production and fewer large owners is likely. Shale rocks laden with oil and gas won’t go away, but the pecking order in the patch will change — bigger players that are more financially solvent, better control over financial risk, and more awareness that shale is a marginal swing supplier will define the industry.

Another known unknown is who blinks in the Saudi-Russia stare-down. Their ability to keep warring is limited — the Russian state budget needs oil at about $42 per barrel to break even, and the Saudis need about double that level. These autocrats have learned that staying in power by sprinkling cash on squeaky groups is expensive. The autocrats know that, and I expect quick blinking.

A more interesting unknown is how the cutbacks in the rest of the industry will affect global supply. The consultancy IHS Markit has forecast that the pandemic is already slashing capital expenditures for this year by about 30%, with no recovery in sight, and in some segments of the industry the cuts are already much deeper. For comparison, after the plunge in oil prices in 2014, capital expenditure in the oil and gas exploration and production industry halved, yet output wasn’t much affected. The industry got a lot more efficient at converting dollars invested to dollars of product. Whether much fat still exists is hard to say — all fat in complex supply chains is imaginary until a knife is wielded and new contracts are signed — but most experts see the cutbacks this time having a larger proportional impact on output.

The oil story is in the news daily, with lots of terrific commentary (such as here, here, here and here). But other parts of the energy industry are important for forecasters to study because they reveal how different kinds of state and market incentives lead to very different outcomes.

At the top of my list is electricity. Demand has fallen, of course, as industries close their doors or cut back production. In the first week of Italy’s lockdown, total daily power demand dropped about one-tenth and the prices for electricity (trading a month into the future) declined by nearly one-third. Looking across several markets as they contract, the savings from staying at home — and the decline in industrial activity — has altered the load curve in interesting ways. It turns out that when humans can choose their daily schedule — not dragging themselves to school, a factory, the office, or an airport at dawn — they for the most part, like sleeping in. And while overall demand hasn’t declined that much — relative, say, to the plunge in the oil industry — peak demand during the middle of the day is way off. Italian demand during the middle of the day has dropped one-third with factories and retail shops closed; key U.S. markets, starting in New York, are on track for similar noonday erosion. The Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI) has started tracking the trends to help grid operators understand their futures as the pandemic spreads.

The segment of the electricity industry that is taking this most in stride are companies that run nuclear power plants. Supplies on site are stockpiled — nuclear plants use a lot of protective gear that is now in short supply in the rest of the economy (e.g., masks, clean suits) during critical operations, for example. Emergency plans, such as to defer some maintenance and alter work hours, are triggered. The mindset of planning for emergencies is well ingrained — especially in nuclear power but also in nearly every corner of the core electric power industry — and the incentives from regulators and corporate strategists focus on reliability.

Electric power, more than any other element of the global energy industry, will reveal the rising importance of the state.

Electric power, more than any other element of the global energy industry, will reveal the rising importance of the state. Where returns are highly regulated, well-managed incumbent electric firms will remain financially sound. The places where the industry is most exposed to pandemic impacts are those with long, complex, and fragile supply chains. The worst impacts are probably in the solar industry. China’s shutdown slowed supplies from the world’s largest producer of solar panels; those are now arriving in the U.S. market, just as workforce sequestration and stress are adding new delays. Meanwhile, the economics of solar projects depend on a tax credit that will start shrinking at the end of the year — a deadline for getting projects online that, if missed, will have severe financial consequences for developers. One immediate effect of the pandemic is a big rethinking about supply chain fragility — something that is long overdue and began, already, when trade wars began exposing these risks. The pecking order seems likely to shift away from firms that are financially fragile and toward size and reliability. Look for firms in solar industry, which has long celebrated its rise in market competitiveness, to look back to the state for help.

One of the good things about the pandemic for forecasters is that the shock forces a reckoning with just how sharply things can change. It parades black swans before our eyes and forces us to update mental models. It is critical that analysts not miss the opportunity, mid-crisis, to explore the full extent of extreme outcomes. For example, alongside the chaos of the pandemic there are anecdotal reports of rising cyberattacks — the extreme scenario the industry had already been planning to handle. We should be looking at robustness of systems in the face of multiple correlated shocks — conjoined Siamese black swans.

In the power industry, the loss of demand offers another opportunity for experiencing the future that must not be lost. With lower demand comes lower use of fossil fuel plants — and higher fractions of renewables on the grid. Making those grids reliable is a big challenge that arrives, for most grid operators, much earlier than they had been expecting.

Back to the future

For the futurists, most of the really bold thinking during the pandemic has revolved around the demand for energy. Indeed, one of the most profound impacts of high prices after the 1970s oil crises was a big reduction in demand. Higher prices and unreliable supplies forced better thinking about how to engineer systems for efficiency — a mindset that is still spreading in influence.

This time around, a big shock in demand seems much less likely — not least because the crisis has driven prices down. At the macro level, the main effect of macroeconomic shocks has been to shift demand sideways. During a recession, demand drops, but then tends to rebound. The figure, which shows total global demand (region by region) has noticeable drops such as in middle 1970s (oil crises and macroeconomic shocks) and 2008 (the last global financial crisis). But what’s most striking is the global trajectory, which rises linearly and inexorably.

Within the big macro perspective, there is plenty of room for pecking orders to shift and for forecasting error. For much of the history of demand forecasting, the errors were on the high side — as Amory Lovins argued presciently after the first oil crisis. Forecasting wasn’t much better than monkeys working with semi-log paper; demand rose exponentially in the past, so it must be assumed the trend would continue. Until last month, many of the forecasting errors ran the opposite direction — experts didn’t take seriously enough that demand would grow robustly. The sledgehammer the pandemic brought is a reminder that the tails of the distribution of possible futures is pretty wide. It’s also important for groups that do forecasting to spend more effort assessing their past performance and learning how to do better.

Looking at the micro-level helps explain why demand, even when hit by a sledgehammer, bounces back. Yet it is here — looking at individual services and technologies — where the thinking, in the midst of a crisis, gets the wooliest. With everyone stuck at home and spending endless hours videoconferencing, it is easy to imagine a future that is a horror show for airlines: minimal travel. It is also easy to forget that the last “death of distance” — as The Economist cover notoriously screamed about the elimination of communication costs in 1995 — was correlated with one of the most robust expansions of global travel in history. The reality is that business and other social activities require direct human interaction. Better videoconferencing will mean more meetings, not fewer trips — along with greater expectations that even when traveling, one should be at meetings back in the home office. Some travel may disappear, but load factors on aircraft may also go down as more people push back against sardine packing of passengers — fewer passengers, with the same airplanes, means more emissions per head. When the airlines were forced to cut back on flights demand for private jet services soared about 300% (a number that will abate once repatriations are over). A private jet loading causes about 10 times the emissions per seat mile as more heavily packed commercial planes.

The history of technological change is full of transformative examples where “everything changes,” but demand is unphased. One is the massive shift from horses to cars — a process that altered the moving vehicle (and radically cut pollution, because horses emit a lot) but didn’t alter the exponential growth in the number of vehicles people wanted on the road, as shown in this figure:

There’s been a lot of wooly thinking about how information technology services — booming even more thanks to Netflix, Disney, YouTube, and the rest — has also had a surprisingly small impact on total demand for energy. For years we have been bombarded by news accounts about how server farms would gobble up huge volumes of electricity. Those dramatic stories led to big forecasting errors because, less visibly, sundry innovations in energy efficiency have kept power demands from soaring. Data services have grown 550% over the last eight years; power consumption rose just 6%.

When the waters drained from today’s economy rise again, the rocks that define how the system works will be harder to see.

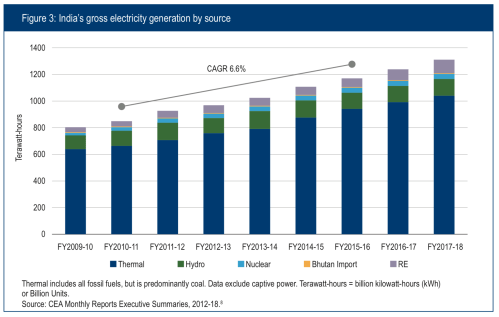

With the rise, again, of states in the pecking order, it will become particularly important for forecasters not to confuse signals that come from prices with those that are rooted in policy. Cheap oil, for example, is unlikely to have much impact on the electric vehicle revolution — because most buying decisions have been the result of direct government policy (e.g., rebates), mandates, and the desire of early adopters to buy cool gear. Economic shock may dampen the willingness of households to make new capital outlays (likely) or governments to pay for incentive programs (so far, no signs of that). Similarly, relatively expensive coal — for the first time in modern history, the cost of coal in the global market is, btu-for-btu, more costly than oil or gas — probably won’t have much impact on coal’s market share in the places where coal has been most dominant: Asia. New coal plants planned for Japan and India, for example, would be backed by long-term contracts. Movements in spot prices don’t change those fundamentals.

When the waters drained from today’s economy rise again, the rocks that define how the system works will be harder to see. Today’s pandemic offers an opportunity for forecasters to test what they know and can predict. We should be writing down our estimates and logic, updating them often, and checking progress. And learning.

Commentary

Forecasting energy futures amid the coronavirus outbreak

April 3, 2020