The spread of the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) has been a disaster for the economy, shown weaknesses in public health systems, and killed several thousand people worldwide. It has also made clear how interconnected the modern world has become. Walls are futile for preventing the rapid movement of the virus around the globe.

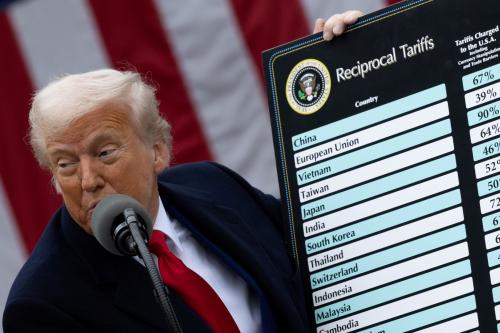

The failure to reach agreement on production cuts at the recent OPEC+ meetings in Vienna has sent oil prices plummeting, marking a return to volatility after a reasonably calm period. This event too shows the interconnection of the world via global markets.

The oil “war” that emerged in Vienna last week between Saudi Arabia and Russia has already affected oil companies and oilfield-services companies, as well as their employees, investors, and local communities. Many energy companies were already highly leveraged and not bringing in sufficient revenue, resulting in declines in market capitalization and jobs. However, there was still hope. That hope has severely eroded over just a week.

This price collapse, oil market experts warn, is different than past crashes. It is a combination of a supply glut with enormous demand loss. Thus, there is no clear precedent for how it might be addressed. The breakdown of the OPEC+ talks will likely have ongoing negative implications for the cartel and its influence.

The price collapse will also negatively influence the U.S. economy, harming not just energy companies, but also services companies and the local communities that oil revenue supports, directly and through taxes.

Another key impact, though, is that prices for gasoline and other products made from oil will drop. Although predicting the balance of positive and negative effects on the overall economy is difficult, many voters in November will not take a holistic look at the situation. Instead, they will likely focus narrowly on how much it costs to fill up their car tanks.

Despite the painful and empirical evidence that we live in an interconnected world, many still take this interdependence as an affront to national sovereignty. They hide within the rhetoric of populism and nationalism.

In the energy sector, the last two secretaries of energy — Rick Perry and Dan Brouilette — used the rhetoric of freedom gas, energy dominance, and energy independence as rallying cries for their great leader and the party.

But now, President Trump has been unable to push back the tide of the virus, nor have he or his party been able to prop up the oil markets. And so people in Texas, North Dakota, New Mexico, and Colorado have become aware of how global markets can deeply affect them, their families, and communities. Decisions made in far-away capitals have a bearing on the daily lives of Americans. The coronavirus has, perhaps, made that even clearer.

While the shale revolution changed the global energy landscape and brought the United States a bump in geopolitical influence, becoming an energy supermajor also brings vulnerability, through greater connectivity.

Energy dominance is nonsense, as is energy independence. “Freedom gas” was absurd from the day it was uttered. The goal, rather, should be real energy security, including resilient economics, communities, and markets. Such a security goal requires a new approach to global energy statecraft, rooted not in boisterous language, but in staid policies and regulations that acknowledge volatility in prices and inevitable geopolitical disruptions. As the energy landscape continues to change and evolve, a pivot towards resilient security will also enable a transition to a sustainable and low-carbon future.

The volatility and uncertainty in energy markets bring an opportunity to redefine a uniquely American energy security for our multi-polar, ever-more connected world. Thus far, the administration’s response to the virus, focused on travel bans and designation of the virus as “foreign,” aren’t encouraging. But crises can also foster cooperation, and an increasingly more interconnected set of energy markets could encourage a more stable, lower-carbon future.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

COVID-19 is a reminder that interconnectivity is unavoidable

March 12, 2020