Japan is a frontline state in the ongoing global health crisis brought about by the emergence of a highly infectious viral disease quickly spreading from China to its neighbors and beyond. The coronavirus crisis stands to deal a severe blow to the Japanese economy, has raised significant questions of the government’s ability to deal with a pandemic, and has altered both domestic political dynamics and Japan’s diplomatic calendar in a landmark year. The associated disease, COVID-19, is likely to extend a large shadow on the remainder of the Shinzo Abe era.

The economy

The economic impact of the coronavirus crisis stands to be severe, hitting Japan at a moment of particular vulnerability. Last October, the Abe administration went ahead with a twice-postponed increase of the consumption tax (from 8% to 10%) in order to cover mounting social security expenses due to the rapid graying of the population. Raising taxes is always a politically perilous proposition, but especially so in Japan, where past tax hikes have resulted in sharp economic contraction (both in 1998 and 2014). The Abe government insisted it had learned these lessons and had readied countermeasures to make any economic dip short-lived. And it remained steadfast in insisting that only a Lehman Brothers-type shock (the collapse of the large American financial firm, which marked the onset of the global financial crisis of 2008) would justify yet another postponement. Banking on five years of continued economic expansion in Japan, the government went ahead with the consumption tax increase last fall.

A new pathogen triggering a global pandemic is the ultimate black swan. For Japan it has brought back the prospect of a recession, as it negates the possibility of a V-shaped recovery from the severe downturn registered in the last quarter of 2019: an annualized contraction of 7.1% with sharp drops in business investment and private consumption. Moreover, the nature and geography of the COVID-19 outbreak present formidable challenges for the engines of Japanese economic growth. The social distancing measures that are essential to mitigate the spread of a communicable disease will only further dampen consumption and discourage business investment. The tourism boom (with the goal of 40 million visitors in the year of the Olympics) is now irremediably compromised. The near standstill over the past few weeks of the Chinese economy, Japan’s largest trading partner, represents both a demand and supply shock with large Japanese auto firms already cutting production in some factories at home due to disruptions in supply chains.

Japan’s ill-starred fate is that the worst economic downturn since the global financial crisis came on the heels of its own domestic contraction. With the new facts on the ground, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has revised downward Japan’s growth rate for 2020 from 0.6% to 0.2%. But the outlook continues to deteriorate with the plunge of the oil market, the pronounced appreciation of the yen, and the fall of the Nikkei stock market below 20,000 points.

Government competence

The Japanese public, like every other public, is most concerned with the competence (or lack thereof) of the government in dealing with this public health crisis. Confirmed cases of coronavirus in Japan currently surpass 1,000, with most of them (700) originating from the Diamond Princess cruise ship. The handling of the quarantine on the ship has been the subject of great scrutiny, with increasing reports of lax protocols undermining the effort to contain the disease aboard and possibly after passengers disembarked.

Decisions on travel restrictions have also been controversial. For weeks, the Japanese government only applied curbs on Chinese visitors from the epicenter of the outbreak in Hubei province, and it was not until March 9 that more stringent border controls became operative. Henceforth, visitors from China and South Korea can only land on two designated airports, must self-quarantine for two weeks, and tourist visas are temporarily rescinded — a move that triggered a sharp rebuke from South Korea.

As cases of community dissemination continue to grow and testing for COVID-19 moves at a sluggish pace, broader questions have emerged on the government’s ability to act decisively. Without question the Abe team has boosted Japan’s executive decisionmaking capabilities: The prime minister’s office has operated as a “control tower” taming endemic bureaucratic sectionalism, and it instituted a new National Security Council to provide a whole-of-government response to Japan’s national security threats.

But COVID-19 bedevils these structures. For one, it requires infection disease experts, not bureaucrats, to be on the lead, and Japan does not have a Centers for Disease Control-like organization. But it also raises thorny questions about how much the government can impinge on personal freedoms for the sake of a national emergency. In fact, the government has found the extant legal framework wanting, pushing instead for a new special emergency law that will only be voted upon this week, further delaying more forceful action.

Politics

Crises always have consequences, and COVID-19 has already made its weight felt on Japan’s diplomatic calendar and domestic political dynamics. Prime Minister Abe is already the longest-serving prime minister in Japan’s history, but some political observers entertained the possibility of a longer tenure if the party moved to award Abe a fourth term beyond 2021. The American presidential election figured prominently in that scenario as one of Abe’s strong suits is to be a “Trump whisperer” of sorts — shielding Japan from the risks of a president skeptical of alliances and trade. But a more immediate scenario has intruded, one where public disenchantment with the Abe government’s response to the coronavirus (with a drop of 8% in public support in the last few weeks) gives new impetus to Abe’s rivals and would-be successors within the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP).

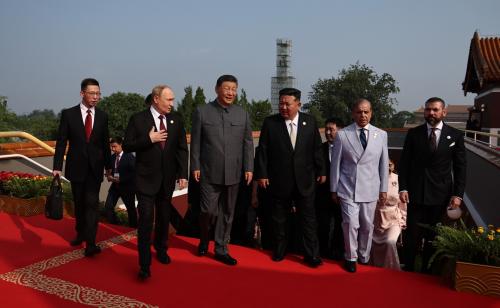

2020 was geared to be a major year for Japanese diplomacy, with a number of signal events that would also marshal Prime Minister Abe’s legacy. A state visit by President Xi Jinping to herald the stabilization of Japan-China relations has been postponed. And the fate of the summer Olympics hangs in the balance of a still little-understood new global health risk.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

COVID-19 may yet rewrite the Abe era in Japan

March 9, 2020