At 3pm on July 15, 1958, 1,700 U.S. Marines stormed the beaches of Beirut. They were ready for combat, weapons loaded, and backed up by a full 70 warships in the Mediterranean Sea (including three aircraft carriers: the USS Essex, USS Wasp, and USS Saratoga). Back in the United States, the 82nd Airborne Division was on alert in case more troops were needed.

But the terrain they encountered was hardly a battlefield. Lebanese and foreign sunbathers — some in bikinis, the 1950s innovation in lady’s swimwear — scrambled for cover. Lebanese vendors quickly appeared with carts selling cigarettes, cold drinks, and sandwiches for the American soldiers. Scores of Lebanese teenage boys soon arrived to gawk at the scene, eager to help the Marines set up their equipment.

It was America’s first-ever combat operation in the Middle East. American troops had been in the Middle East since World War II, but not in combat. America had built an airbase in Saudi Arabia, for example, but it had never been used to fight.

No one in Beirut — or Washington — thought that this mission would mark the beginning of decades of seemingly endless American combat missions in the Middle East.

No one in Beirut — or Washington — thought that this mission would mark the beginning of decades of seemingly endless American combat missions in the Middle East. In retrospect, Beirut in 1958 was a decisive turning point.

The view from Washington

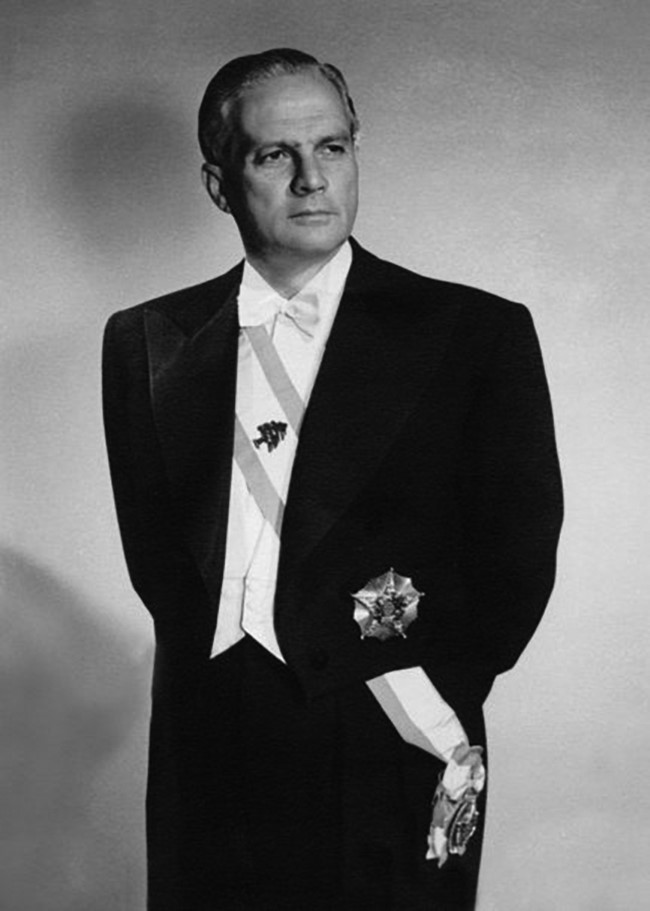

Although the landing was comical, it was also deadly serious. Lebanon was in the midst of a civil war pitting the Christian and Muslim communities against each other. The Muslims saw the Marines as enemies intent on keeping a hated President Camille Nemr Chamoun in office against the law. The Lebanese army, a fragile coalition of Christians and Muslims, saw the Marines as uninvited aggressors who were violating Lebanese sovereignty. The American command was prepared for the worst and was ready to deploy nuclear weapons to the battlefield from its base in Germany.

Back in Washington, President Dwight Eisenhower — hero of the 1944 D-Day landings — addressed the nation. A year before, Eisenhower had enunciated what became known as the Eisenhower Doctrine, the first statement by a president stating that America has vital interests in the Middle East and would defend them by force if necessary. Now the president addressed the situation in the region. He began by discussing the immediate cause for the dispatch of the Marines: a coup d’etat in Baghdad on July 14. The pro-American King Faisal II had been brutally murdered in the coup, and his government was swept away. In Jordan, then federated with Iraq, Eisenhower said a “highly organized plot to overthrow the lawful government” of King Hussein had been discovered. Actually, the Central Intelligence Agency had foiled the plot several weeks before.

Eisenhower then turned to Lebanon, and said President Chamoun had requested American military intervention to stop “civil strife actively fomented by Soviet and Cairo broadcasts.” It was the only time in the speech that Eisenhower even alluded to what had him really worried that day: the rising political power in the Arab world of Egypt’s charismatic young President Gamal Abdel Nasser and his Arab nationalist movement.

Instead, the president spoke in Cold-War terms. Lebanon, the size of Connecticut, was under threat by the Soviet Union. Just as the Soviets had taken over Czechoslovakia and China, they threatened Lebanon. The United States must act to defend Lebanon, he contended, or there would be another Munich-like appeasement of dictatorship which would surely lead to another world war.

It was a less than candid explanation for sending in the Marines. Eisenhower made no mention of the fact that Chamoun was illegally seeking a second term and even claimed Chamoun did not seek reelection. The focus was entirely on Russia and the Cold War, an issue far more Americans understood than the intricate politics of Lebanon or the Arab world.

The view from Egypt

Nasser, meanwhile, was in Yugoslavia visiting the communist government there. Within hours of Eisenhower’s speech, he flew to Moscow. Both Nasser and his host Nikita Khrushchev agreed that they had no warning of the coup in Baghdad or knew anything about the coup plotters, according to recently declassified Soviet documents. Both agreed that the Iraqi coup was the most important development in the Middle East and the American intervention in Lebanon was a sideshow.

Nasser was, in the summer of 1958, at the pinnacle of his political career and power. Ironically, he had started his political rise very much as a protégé of the Americans. Born in Alexandria in 1918, Nasser had gotten into politics early in life as an opponent of the British colonial masters of Egypt. He joined the army and fought heroically in the 1948 war against Israel. He was the mastermind behind the 1952 coup that ousted the monarchy and created the first Egyptian-led government in two thousand years. He was handsome, articulate, and charismatic.

The British had been completely surprised by the coup in Egypt, but the CIA was not — it had detected the signs of change coming. The agency moved quickly after to coup to establish contact with Nasser. The point man for the CIA was the legendary Kermit “Kim” Roosevelt, a scion of the Roosevelt family born in Argentina. Kim had visited Cairo before the coup and set up contact with the Free Officers who would carry it out. In October 1952, he returned to Cairo as chief of the CIA’s Near East Division and met with Nasser at the famous Mena House Hotel near the pyramids. Each was impressed by the other and they agreed to a clandestine relationship.

Nasser was, above all else, an Egyptian nationalist determined to remove all the vestiges of British colonialism, including the large military base that London still operated in the Suez Canal region. He also espoused Arabism, the drive for unity of the Arab peoples from Morocco to Oman. He was a resolute opponent of European colonialism around the world, but especially in Africa. Roosevelt believed the United States could work with Nasser.

After Eisenhower was inaugurated in January 1953, the CIA got new leadership. Allen Dulles was the brother of Eisenhower’s Secretary of State John Foster Dulles. Allen had served in the CIA’s predecessor, the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) in Switzerland during World War II, and was a proponent of covert action to achieve America’s strategic goals by clandestine, CIA-led operations. Roosevelt led the CIA operation that overthrew a democratically elected government in Iran and restored the Shah to his throne in 1953, immediately making him the darling of both Dulles and Eisenhower.

The secretary of state visited Egypt in May 1953 and was also impressed by Nasser. Washington agreed to encourage the British to give up their Suez Canal base. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill was initially reluctant, but the U.K.’s huge debts from the world wars compelled him to make a deal and the British army agreed to leave Egypt in 1954. Roosevelt had been active behind the scenes in facilitating the deal.

The Egyptians wanted to acquire modern weapons for their military. The CIA gave Nasser a few million dollars, far short of what he wanted, to buy arms. Instead, he used it to build a large transmitter for the Egyptian radio program the “Voice of the Arabs” and broadcast his Arabist and anti-colonialist message to the region. Word spread about the source of the money for the tower, and it was nicknamed “Roosevelt’s Erection.”

By then, the relationship between Washington and Cairo was cooling fast. Nasser took a decisive step when he arranged a large arms purchase from the Soviet Union’s client state Czechoslovakia in 1955. This alarmed the Cold Warriors in the West, especially John Foster Dulles, who saw the arms deal as the first significant penetration of the Middle East by Russia. It also alarmed the British and French, who saw Nasser’s growing stature as a threat to their remaining colonies and protectorates in the region such as Aden (part of modern-day Yemen), Algeria, Jordan, and Iraq. Israel felt directly threatened. Eisenhower opposed the 1956 tripartite invasion of Egypt by Britain, France, and Israel, seeing it as a throwback to imperialism, but the crisis did not improve the American relationship with Nasser.

By 1958, the year of the U.S. operation in Lebanon, the American image of Nasser had evolved from courageous freedom fighter to evil tool of Moscow, a threat to American and Western interests in the entire region and the Third World. Early that year, Egypt and Syria united into the United Arab Republic and openly called for other Arab states to join them. Nasser traveled to Syria and was greeted by vast crowds of enthusiastic admirers, including 350,000 Lebanese (out of a total population of 1.5 million). Nasser’s intelligence agents unveiled a Saudi-funded plot to assassinate him, severely embarrassing King Saud, the man Eisenhower hoped would be a pro-American alternative to Egypt for the Arab public. Civil war broke out in Lebanon when Chamoun endorsed the Eisenhower Doctrine and appealed for American support for his reelection. Washington was gravely alarmed by events in the region by the summer.

The view from Iraq and Jordan

The July 14 coup in Baghdad was a complete shock. A brigade of troops was scheduled to pass through the capital en route to Jordan to help back King Hussein against the threat posed by Nasser. Instead, as it entered the capital, it turned on the monarchy. The rebels surrounded the royal palace, and when it surrendered, the king and regent were shot to death. It was a bloody affair. The tanks of the coup-makers were covered with pictures of Nasser, and the crowds that cheered the Iraqi monarchy’s demise also screamed for Gamal Abdel Nasser. The military leaders of the coup said very little.

The coup came as a nasty surprise for Jordan’s King Hussein. His family members had been brutally murdered. He was formally now the king of the federation of Iraq and Jordan, which was created in the wake of the announcement of the Syria-Egypt United Arab Republic. At first, Hussein considered sending troops to Baghdad to reverse the situation — but it became clear that the coup had overwhelming popular support and the backing of the entire military.

Back in Washington

The news of the Iraq coup prompted Eisenhower to hold an emergency meeting of the National Security Council principals. It began with a briefing from CIA Director Allen Dulles. Dulles said that information was very incomplete, but the coup had decapitated the royal family. The rebels were carrying Nasser placards, and the mob was chanting Nasser’s name.

On the regional implications of the coup, he painted a bleak picture: Lebanon’s Chamoun was already asking for American troops, and Jordan was acutely vulnerable. “If the Iraq coup succeeds it seems almost inevitable that it will set up a chain reaction that will doom the pro-West governments of Lebanon and Jordan and Saudi Arabia, and raise grave problems for Turkey and Iran.” Israel, Dulles predicted, would take over the West Bank and East Jerusalem “if Jordan falls to Nasser.” The entire Middle East — or at least its Arab components — might fall to Nasser, in his view. Russia would be the beneficiary.

Allen’s brother, the secretary of state, chimed in with a long analysis on how the Soviets were behind Nasser and stood to gain control of a block of states from Morocco to Indonesia. The president concluded the meeting by saying that it was clear in his mind “that we must act or get out of the Middle East entirely.” At risk was a devastating defeat in the Cold War, even worse than the loss of China to communists a decade earlier.

The White House instructed the Pentagon to send the Marines ashore in Beirut the next day. Operation Blue Bat was the code name. In London, the British government decided to send paratroopers to Amman to help steady the remnant of the Hashemite monarchy still in power there.

Ike was lucky in the end. His diplomats and generals on the scene in Beirut found a diplomatic way to avoid conflict and prevent the worst. The nuclear weapons were never shipped from Germany to the Mediterranean. After a period of political negotiations, Chamoun was pressured to stand down as president, and the civil war ended.

Subsequent American combat missions in the Middle East would not be so lucky or so cost-free. The return of the Marines to Beirut in 1982, for example, ended in a catastrophic truck bombing of their barracks that killed 241 soldiers. The wars in Iraq have now seemingly become endless. The region itself is constantly in turmoil, with terrorist attacks in many of its capital cities an all too routine atrocity.

I was a witness to the events in Beirut in 1958 — my father worked for the United Nations there. Only five years old in July 1958, I was too young to understand much of what was going on around me, but I suspect my interest in the region and its politics has its origins in those eventful days.

Commentary

Beirut 1958: America’s origin story in the Middle East

October 29, 2019