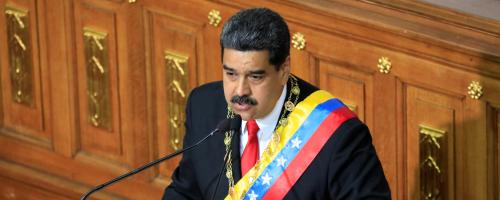

Writing in The National Interest, Juan Carlos Pinzon Bueno and Michael O’Hanlon warn that “even if things do not get that bad, it is easy to imagine scenarios in which ten million Venezuelans become refugees — with many millions inside the country struggling just to stay alive as food supplies dwindle and public health conditions deteriorate even further.”

With its economy in free fall, after having already contracted by half this decade, and with its future politics completely up in the air as President Nicolas Maduro clings semi-constitutionally to power, Venezuela teeters on the brink. Already one of the world’s most crime-afflicted countries, it risks becoming something closer to a failed state in future months. Think of Somalia or Libya, but several times larger in population and several times closer to the United States. For Colombia, Brazil, Guyana, and Caribbean island nations like Trinidad and Tobago, Venezuela and its thirty-one million people are right next door. Refugee crises in North Africa and the Middle East have been getting more of the news coverage, but already the human flows out of Venezuela have reached comparable magnitudes — and, with the U.S. oil embargo kicking in, the scale of the problem may soon get much worse. The United States and Colombia should therefore take the lead in planning for what could become, in a plausible worst case, the collapse of Venezuela. Even if things do not get that bad, it is easy to imagine scenarios in which ten million Venezuelans become refugees — with many millions inside the country struggling just to stay alive as food supplies dwindle and public health conditions deteriorate even further.

Bogota and Washington should begin this planning process and bring other regional countries into the discussions in short order. Yes, talks like this have already happened between American and Colombian officials, at a broad conceptual level, over the last several years. But it is doubtful that military planners in either country are really ready for that 3 a.m. phone call from their respective presidents when a major event inside of Venezuela threatens imminent catastrophe. It is time to get ready.

It makes sense for this planning process to begin with the United States and Colombia because the alliance between our two countries is particularly close. Thanks to the last four American presidents and the Colombian Armed Forces, Colombia has cut its violence by two-thirds from peak levels, seriously weakened several international drug cartels, and reached a peace deal with the FARC — admittedly a controversial peace that is now fraying and bringing new risks. Far more needs to be done, including on the counternarcotics front, but through Plan Colombia and its second phase (Peace Colombia), the two countries have proven that their bilateral alliance is second to none in the hemisphere.

Colombia also has a special interest in this problem because it is the largest country with major parts of its population in close proximity to Venezuela. All neighbors will bear the brunt of any dramatic downward spiral in Venezuela’s economy and stability, but Colombia and its fifty million people are particularly poised to suffer the consequences.

FARC remnants as well as another dangerous group, the ELN, use Venezuelan territory for narcotrafficking and illegal mining, many times with the support of Venezuelan regime. Tragically, the 2019 car bomb at the Colombian Police Academy, when twenty-two young cadets were killed, was ordered by ELN commanders from Venezuelan territory.

With one of the region’s largest and best-resourced militaries, despite some unfortunate readiness trends since 2015, Colombia is well placed to do its part in responding to any emergency. Its defense budget of $10 billion is second only to Brazil’s in Latin America; the size of its active-duty military, with nearly 300,000 personnel, is also second only to Brazil. Along with the United States (as well as Trinidad and Tobago) it is the only country in the hemisphere to devote at least 3 percent of GDP to its armed forces. Colombians take their security and their security responsibilities seriously.

To be clear, the kinds of military operations that we currently favor planning to conduct are specific and limited in nature. Excepting some covert revolutionary activity by one or two states, mostly in the form of proxy warfare, Latin American nations do not fight each other. Ecuador and Peru’s longstanding border dispute, which led to a skirmish in 1981 and a brief conflict in 1995, is the last significant incident, and has since been resolved. Despite the Venezuelan government’s brutality and human rights violations against its own people, as well as its failed pseudo-Marxist policies, neither Colombia nor any other Latin American country, we are confident, will propose or support a regime-change operation in Venezuela. Nor does President Donald Trump seem interested in such a possibility. Other options could be considered if the situation continues to deteriorate.

However, more limited yet still large contingencies are entirely plausible. Containment of any refugee flows, protection of innocents, and in a worst-case scenario, stabilization of parts of the country after the government collapses are all possibilities that cannot be dismissed. As one part of the response, it could be necessary to create, protect, and provide supplies for a large area in which displaced populations could take refuge — either just outside of Venezuelan territory or, depending on conditions on the ground as well as the desire of the U.N. Security Council, perhaps within it. Such a safe zone would require armed force, but only for defensive purposes near and within the safe haven. This kind of zone could not possibly suffice for the systematic relief of the suffering of the nation’s population. But it could provide a sanctuary for dissidents, a possible safety valve for some of the deprived population, and potentially a location where a future opposition government could establish some degree of sovereign rule in what could temporarily become a divided country. This last element of the concept makes it highly fraught. But if Venezuela descends toward a state of not just large-scale hunger but widespread starvation, then it could be our least bad option. Due to the fact that extremist groups are using Venezuelan territory to plot attacks on Colombia, targeted military operations against them may soon be needed, if Venezuela’s government cannot police and control its own territory.

For those who worry that this kind of thinking is militarizing a problem best addressed diplomatically, we would offer two responses. First, we agree in principle—but the hour for diplomacy may be fast receding, and if it fails completely, a massive humanitarian disaster could quickly present itself whether we would wish that or not. Second, this would not primarily be a combat operation in all likelihood, even if it would require combat-capable units. Much of the planning needed to handle this kind of contingency is about the logistics of providing food and water and medical supplies to large numbers of people. In dangerous environments, with large human population flows, it is often only military forces that can address the magnitude of the problem — aided, to be sure, by numerous humanitarian organizations from Colombia, the broader region, the United States, and the international community. Military organizations are also equipped to do large-scale and centralized planning in a way that no other agency may be able to provide for the kind of catastrophe that could now be brewing.

We need to be ready for that 3 a.m. call. Hopefully it will never happen. But it could come any time.

Commentary

Get ready for the Venezuela refugee crisis

September 10, 2019