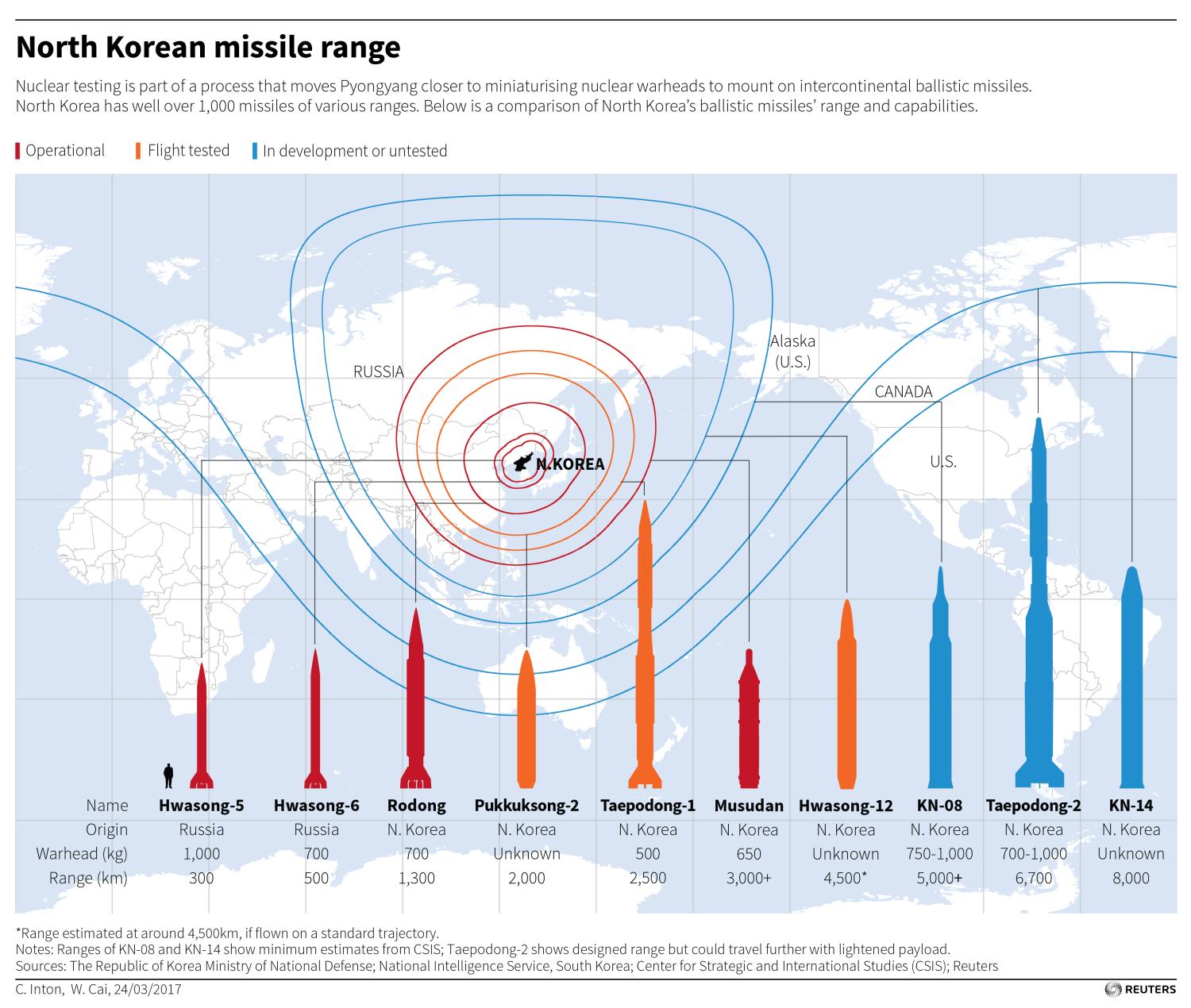

North Korea’s successful test of its first-ever intercontinental ballistic missile represents a clarifying moment in decades-long arguments about U.S. policy toward America’s longest running international adversary. The North’s engineers opted to let its Hwasong-14 missile fly high rather than fly far, enabling it to splash down in Japan’s exclusive economic zone, thus avoiding the much larger risks and uncertainties of flying over Japanese territory. Had the missile flown on a more normal trajectory, it would have surpassed 5,500 kilometers, the standard threshold for a missile of ICBM range.

The decision in favor of a highly elevated trajectory denied Pyongyang a singular “Sputnik moment” in the eyes of the outside world, but the consequences are much the same. The North now possesses a missile capable of reaching Alaska and possibly some of the lesser islands of the Hawaiian chain. Even more important, North Korean technical personnel claimed that the simulated nuclear warhead used during the test fully withstood the extreme heat and additional pressures associated with the reentry process.

Though there is no readily available means to evaluate such claims, it would be imprudent to dismiss them. Over the past year and a half, the technological progress in North Korea’s strategic weapons programs has appreciably accelerated. Future missile tests will attempt to fly farther and refine warhead technology, presumably enabling Pyongyang to put the continental United States or substantial portions of it at risk. Given sufficient time and effort, North Korea is ultimately expected to achieve an operational nuclear capability able to reach the United States; with the success of the latest test, some analysts believe it may already possess this capability.

Plus ça change…

To numerous American observers, including many former senior policymakers, the July 4 missile test definitively alters U.S. strategic calculations. But does it? North Korea’s far more immediate and persistent threats are to the peninsula and to the region, where it endangers the lives of large numbers of American military and civilian personnel and far larger numbers of Korean and Japanese citizens. These remain incontrovertible facts.

The fundamental mission of American military power deployed on or near the Korean peninsula has long been to deter renewed North Korean aggression or related coercive actions. Should deterrence fail, the core mission is to defend U.S. allies and to defeat the North. Despite the persistent and now enhanced North Korean threat, both Japan and South Korea have developed as close U.S. allies and major industrial democracies. North Korea’s ability to reach the United States with an ICBM does not alter the essential purposes of U.S. policy; if anything, it should reinforce it.

The enhanced strategic reach of a deeply antagonistic regime that throughout its history has deemed the United States its sworn adversary is deeply disquieting. When Kim Jong-un, the North’s absolute ruler, declared in a New Year’s Day address that North Korea was in the “final preparation stages” for its first ICBM test, then-President-elect Trump tweeted days later that “it won’t happen!” Now it has.

North Korea just stated that it is in the final stages of developing a nuclear weapon capable of reaching parts of the U.S. It won't happen!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) January 2, 2017

But frustration over North Korea’s act of defiance is nothing new, nor should it cloud judgment about how the United States needs to evaluate the risks and respond to Pyongyang’s actions. There are five underlying American fears. The first is that Kim Jong-un is incapable of rational judgment and therefore cannot be deterred. The second is that possession of a long-range missile will allow Kim to decouple the United States from its regional allies and will enable him to pursue coercive actions against South Korea and Japan that he would otherwise not risk, lest the U.S. retaliate.

The third (a corollary of the second) is that Kim’s enhanced missile reach will severely undermine Korean and Japanese confidence in U.S. extended deterrence guarantees. This would ultimately lead both close U.S. allies to pursue nuclear weapons programs of their own, doing irreparable damage to the non-proliferation regime and to the regional security order. The fourth is that a highly isolated, cash-deprived regime will engage in illicit export of nuclear technology and materials to others intent on covert nuclear programs of their own. The fifth is that fissures and vulnerabilities in the North Korean system will ultimately undermine central control of Pyongyang’s nuclear and missile assets, triggering larger and unpredictable consequences.

None of these expressed fears can be summarily dismissed, and all would represent dire and dangerous outcomes. Several find precedents in prior North Korean actions. The operative issues for the foreseeable future are how the United States can act to render all five fears as remote as possible; disabuse Pyongyang of any belief that its recent successes will lead the U.S. to accept it as a nuclear power; and elicit as much international cooperation as possible to address its major worries.

Things not to do

Certain proposed courses of action are clearly off-base.

Calls for preemptive military action or outsourcing the issue to China are simply not credible. The former case would entail incalculable levels of destruction and loss of life in South Korea and Japan, including to American citizens and military personnel. The latter case presumes that Beijing will act on America’s behalf in ways that it seems wholly unprepared to take at present. Though we should make every effort to elicit enhanced cooperation from Beijing, no one should assume that we will receive it, nor should the United States fail to act in the absence of active Chinese support.

At the same time, widespread calls for renewed U.S. negotiations with North Korea make little sense. What would Washington and Pyongyang negotiate about? Is the United States truly prepared to make major concessions to the North that (to judge by the long, sad record of prior negotiations with the regime) are reversible or unverifiable, and would directly undermine South Korea’s confidence in its U.S. ally? Moreover, is there any evidence that North Korea’s nuclear weapon and missile programs are negotiable on terms the United States and its close allies would deem remotely acceptable? Buying time is not a credible option.

A better way

The only viable path is one that acknowledges the reality of the North’s nuclear weapons and missiles while explicitly denying any political legitimacy or implied permanence to these programs, and raises the costs to Pyongyang for its actions. We cannot expect to fully understand Pyongyang’s calculus of risk, but measures explicitly designed to heighten the pressures on the regime are essential. This must extend to greatly strengthened efforts to deter any coercive actions directed against U.S. allies, much enhanced defense measures in close collaboration with South Korea and Japan, and denial of North Korean opportunities for licit or illicit dealings with the outside world that help advance its weapons programs.

Equally important, the U.S. must continue to impart to Beijing that all U.S. actions are directed exclusively against the dangers posed by North Korea to the vital interests of the United States and its allies. At the same time, Washington must convey to China that it remains fully prepared to work with Beijing against the dangers that Pyongyang represents to both countries. The United States must do all that it can to avoid the Korean peninsula again becoming a conflict zone between the two countries.

U.S. and Chinese interests are not wholly aligned. China seems unprepared to undertake actions in its immediate backyard that it believes will prompt Pyongyang to adopt an overtly adversarial stance toward Beijing. But Washington must unequivocally convey to China that it will act to protect its vital interests with or without Beijing’s concurrence. Notwithstanding formulaic calls from Beijing for a U.S. dialogue with Pyongyang, the Chinese do not object to U.S. heavy lifting on these issues, and might even privately welcome them.

Such measures lend no assurance that there is an easy or early solution in dealing with a dangerous and endangered regime. But comprehensive denuclearization is not a viable near-term goal, and policymakers should avoid making any such claims. Risk minimization must remain the utmost goal now that Kim Jong-un has opted to double down on his nuclear and missile wager.

After decades of effort to understand Pyongyang’s evident belief that nuclear weapons are the ultimate guarantee of its survival and well-being, the deeper animating impulses of the Kim regime (beyond sustaining the family dynasty in power) remain impenetrable. The United States must continue to emphasize to the North that its strategic pursuits are a dead end, and are ultimately destined not to end well. But there is no realistic alternative to preparing for all eventualities if the peace and security of Northeast Asia and the viability of the non-proliferation regimes are to be upheld.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

North Korea has tested an ICBM. Now what?

July 6, 2017